Задание №6332.

Чтение. ЕГЭ по английскому

Прочитайте текст и заполните пропуски A — F частями предложений, обозначенными цифрами 1 — 7. Одна из частей в списке 1—7 лишняя.

A constitution may be defined as the system of fundamental principles according to ___ (A). A good example of a written constitution is the Constitution of the United States, formed in 1787.

The Constitution sets up a federal system with a strong central government. Each state preserves its own independence by reserving to itself certain well-defined powers such as education, taxes and finance, internal communications, etc. The powers ___ (B) are those dealing with national defence, foreign policy, the control of international trade, etc.

Under the Constitution power is also divided among the three branches of the national government. The First Article provides for the establishment of the legislative body, Congress, and defines its powers. The second does the same for the executive branch, the President, and the Third Article provides for a system of federal courts.

The Constitution itself is rather short, it contains only 7 articles. And it was obvious in 1787 ___ (C). So the 5 th article lays down the procedure for amendment. A proposal to make a change must be first approved by two-thirds majorities in both Houses of Congress and then ratified by three quarters of the states.

The Constitution was finally ratified and came into force on March 4, 1789. When the Constitution was adopted, Americans were dissatisfied ___ (D). It also recognized slavery and did not establish universal suffrage.

Only several years later, Congress was forced to adopt the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, ___ (E). They guarantee to Americans such important rights and freedoms as freedom of press, freedom of religion, the right to go to court, have a lawyer, and some others.

Over the past 200 years 26 amendments have been adopted ___ (F). It provides the basis for political stability, individual freedom, economic growth and social progress.

1. which are given to a Federal government

2. because it did not guarantee basic freedoms and individual rights

3. but the Constitution itself has not been changed

4. so it has to be changed

5. which a nation or a state is constituted and governed

6. which were called the Bill of Rights

7. that there would be a need for altering it

Решение:

Пропуску A соответствует часть текста под номером 5.

Пропуску B соответствует часть текста под номером 1.

Пропуску C соответствует часть текста под номером 7.

Пропуску D соответствует часть текста под номером 2.

Пропуску E соответствует часть текста под номером 6.

Пропуску F соответствует часть текста под номером 3.

Показать ответ

Источник: ЕГЭ-2018, английский язык: 30 тренировочных вариантов для подготовки к ЕГЭ. Е. С. Музланова

Сообщить об ошибке

Тест с похожими заданиями

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed.[1] These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is. When these principles are written down into a single or set of legal documents, those documents may be said to comprise a written constitution.

Constitutions concern different levels of organizations, from sovereign states to companies and unincorporated associations. A treaty which establishes an international organization is also its constitution in that it would define how that organization is constituted. Within states, whether sovereign or federated, a constitution defines the principles upon which the state is based, the procedure in which laws are made and by whom. Some constitutions, especially written constitutions, also act as limiters of state power by establishing lines which a state’s rulers cannot cross such as fundamental rights.

The Constitution of India is the longest written constitution of any sovereign country in the world,[2] containing 444 articles,[3] 12 schedules and 94 amendments, with 117,369 words in its English language version,[4] while the United States Constitution is the shortest written constitution, at 7 articles and 27 amendments.[5]

Etymology

The term constitution comes through French from the Latin word constitutio, used for regulations and orders, such as the imperial enactments (constitutiones principis: edicta, mandata, decreta, rescripta).[6] Later, the term was widely used in canon law for an important determination, especially a decree issued by the Pope, now referred to as an apostolic constitution.

General features

Generally, every modern written constitution confers specific powers to an organization or institutional entity, established upon the primary condition that it abides by the said constitution’s limitations. According to Scott Gordon, a political organization is constitutional to the extent that it «contain[s] institutionalized mechanisms of power control for the protection of the interests and liberties of the citizenry, including those that may be in the minority.»[7]

The Latin term ultra vires describes activities of officials within an organization or polity that fall outside the constitutional or statutory authority of those officials. For example, a students’ union may be prohibited as an organization from engaging in activities not concerning students; if the union becomes involved in non-student activities these activities are considered ultra vires of the union’s charter, and nobody would be compelled by the charter to follow them. An example from the constitutional law of sovereign states would be a provincial government in a federal state trying to legislate in an area exclusively enumerated to the federal government in the constitution, such as ratifying a treaty. Ultra vires gives a legal justification for the forced cessation of such action, which might be enforced by the people with the support of a decision of the judiciary, in a case of judicial review. A violation of rights by an official would be ultra vires because a (constitutional) right is a restriction on the powers of government, and therefore that official would be exercising powers he doesn’t have.

In most but not all modern states the constitution has supremacy over ordinary statute law (see Uncodified constitution below); in such states when an official act is unconstitutional, i.e. it is not a power granted to the government by the constitution, that act is null and void, and the nullification is ab initio, that is, from inception, not from the date of the finding. It was never «law», even though, if it had been a statute or statutory provision, it might have been adopted according to the procedures for adopting legislation. Sometimes the problem is not that a statute is unconstitutional, but the application of it is, on a particular occasion, and a court may decide that while there are ways it could be applied that are constitutional, that instance was not allowed or legitimate. In such a case, only the application may be ruled unconstitutional. Historically, the remedy for such violations have been petitions for common law writs, such as quo warranto.

History and development

Early constitutions

Excavations in modern-day Iraq by Ernest de Sarzec in 1877 found evidence of the earliest known code of justice, issued by the Sumerian king Urukagina of Lagash ca 2300 BC. Perhaps the earliest prototype for a law of government, this document itself has not yet been discovered; however it is known that it allowed some rights to his citizens. For example, it is known that it relieved tax for widows and orphans, and protected the poor from the usury of the rich.

After that, many governments ruled by special codes of written laws. The oldest such document still known to exist seems to be the Code of Ur-Nammu of Ur (ca 2050 BC). Some of the better-known ancient law codes include the code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin, the code of Hammurabi of Babylonia, the Hittite code, the Assyrian code and Mosaic law.

Later constitutions

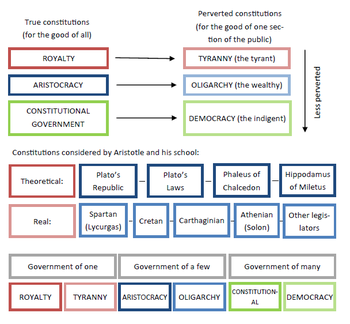

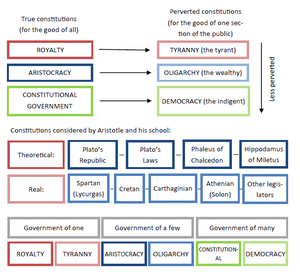

Diagram illustrating the classification of constitutions by Aristotle.

Athens

In 621 BC a scribe named Draco codified the cruel oral laws of the city-state of Athens; this code prescribed the death penalty for many offences (nowadays very severe rules are often called «Draconian»). In 594 BC Solon, the ruler of Athens, created the new Solonian Constitution. It eased the burden of the workers, and determined that membership of the ruling class was to be based on wealth (plutocracy), rather than by birth (aristocracy). Cleisthenes again reformed the Athenian constitution and set it on a democratic footing in 508 BC.

Aristotle (ca 350 BC) was one of the first in recorded history to make a formal distinction between ordinary law and constitutional law, establishing ideas of constitution and constitutionalism, and attempting to classify different forms of constitutional government. The most basic definition he used to describe a constitution in general terms was «the arrangement of the offices in a state». In his works Constitution of Athens, Politics, and Nicomachean Ethics he explores different constitutions of his day, including those of Athens, Sparta, and Carthage. He classified both what he regarded as good and what he regarded as bad constitutions, and came to the conclusion that the best constitution was a mixed system, including monarchic, aristocratic, and democratic elements. He also distinguished between citizens, who had the right to participate in the state, and non-citizens and slaves, who did not.

Rome

The Romans first codified their constitution in 450 BC as the Twelve Tables. They operated under a series of laws that were added from time to time, but Roman law was never reorganised into a single code until the Codex Theodosianus (AD 438); later, in the Eastern Empire the Codex repetitæ prælectionis (534) was highly influential throughout Europe. This was followed in the east by the Ecloga of Leo III the Isaurian (740) and the Basilica of Basil I (878).

India

The Edicts of Ashoka established constitutional principles for the 3rd century BC Maurya king’s rule in Ancient India.

Germania

Many of the Germanic peoples that filled the power vacuum left by the Western Roman Empire in the Early Middle Ages codified their laws. One of the first of these Germanic law codes to be written was the Visigothic Code of Euric (471). This was followed by the Lex Burgundionum, applying separate codes for Germans and for Romans; the Pactus Alamannorum; and the Salic Law of the Franks, all written soon after 500. In 506, the Breviarum or «Lex Romana» of Alaric II, king of the Visigoths, adopted and consolidated the Codex Theodosianus together with assorted earlier Roman laws. Systems that appeared somewhat later include the Edictum Rothari of the Lombards (643), the Lex Visigothorum (654), the Lex Alamannorum (730) and the Lex Frisionum (ca 785). These continental codes were all composed in Latin, whilst Anglo-Saxon was used for those of England, beginning with the Code of Ethelbert of Kent (602). In ca. 893, Alfred the Great combined this and two other earlier Saxon codes, with various Mosaic and Christian precepts, to produce the Doom Book code of laws for England.

Japan

Japan’s Seventeen-article constitution written in 604, reportedly by Prince Shōtoku, is an early example of a constitution in Asian political history. Influenced by Buddhist teachings, the document focuses more on social morality than institutions of government per se and remains a notable early attempt at a government constitution.

Medina

The Constitution of Medina (Arabic: صحیفة المدینه, Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīna), also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib (later known as Medina), including Muslims, Jews, and pagans.[8][9] The document was drawn up with the explicit concern of bringing to an end the bitter inter tribal fighting between the clans of the Aws (Aus) and Khazraj within Medina. To this effect it instituted a number of rights and responsibilities for the Muslim, Jewish, and pagan communities of Medina bringing them within the fold of one community—the Ummah.[10]

The precise dating of the Constitution of Medina remains debated but generally scholars agree it was written shortly after the Hijra (622).[11] It effectively established the first Islamic state. The Constitution established: the security of the community, religious freedoms, the role of Medina as a haram or sacred place (barring all violence and weapons), the security of women, stable tribal relations within Medina, a tax system for supporting the community in time of conflict, parameters for exogenous political alliances, a system for granting protection of individuals, a judicial system for resolving disputes, and also regulated the paying of Blood money (the payment between families or tribes for the slaying of an individual in lieu of lex talionis).

Wales

In Wales, the Cyfraith Hywel was codified by Hywel Dda c. 942–950.

Rus

The Pravda Yaroslava, originally combined by Yaroslav the Wise the Grand Prince of Kiev, was granted to Great Novgorod around 1017, and in 1054 was incorporated into the Russkaya Pravda, that became the law for all of Kievan Rus. It survived only in later editions of the 15th century.

Iroquois

The Gayanashagowa, the oral constitution of the Iroquois nation also known as the Great Law of Peace, established a system of governance in which sachems (tribal chiefs) of the members of the Iroquois League made decisions on the basis of universal consensus of all chiefs following discussions that were initiated by a single tribe. The position of sachem descended through families, and were allocated by senior female relatives.[12]

Historians including Donald Grindle,[13] Bruce Johansen[14] and others[15] believe that the Iroquois constitution provided inspiration for the United States Constitution and in 1988 was recognised by a resolution in Congress.[16] The thesis is not considered credible.[12][17] Stanford University historian Jack N. Rakove stated that «The voluminous records we have for the constitutional debates of the late 1780s contain no significant references to the Iroquois» and stated that there are ample European precedents to the democratic institutions of the United States.[18] Francis Jennings noted that the statement made by Benjamin Franklin frequently quoted by proponents of the thesis does not support for this idea as it is advocating for a union against these «ignorant savages» and called the idea «absurd».[19] Anthropologist Dean Snow stated that though Franklin’s Albany Plan may have drawn some inspiration from the Iroquois League, there is little evidence that either the Plan or the Constitution drew substantially from this source and argues that «…such claims muddle and denigrate the subtle and remarkable features of Iroquois government. The two forms of government are distinctive and individually remarkable in conception.»[20]

England

In England, Henry I’s proclamation of the Charter of Liberties in 1100 bound the king for the first time in his treatment of the clergy and the nobility. This idea was extended and refined by the English barony when they forced King John to sign Magna Carta in 1215. The most important single article of the Magna Carta, related to «habeas corpus«, provided that the king was not permitted to imprison, outlaw, exile or kill anyone at a whim—there must be due process of law first. This article, Article 39, of the Magna Carta read:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

This provision became the cornerstone of English liberty after that point. The social contract in the original case was between the king and the nobility, but was gradually extended to all of the people. It led to the system of Constitutional Monarchy, with further reforms shifting the balance of power from the monarchy and nobility to the House of Commons.

Serbia

The Nomocanon of Saint Sava (Serbian: Zakonopravilo)[21][22][23] was the first Serbian constitution from 1219. This legal act was well developed. St. Sava’s Nomocanon was the compilation of Civil law, based on Roman Law and Canon law, based on Ecumenical Councils and its basic purpose was to organize functioning of the young Serbian kingdom and the Serbian church. Saint Sava began the work on the Serbian Nomocanon in 1208 while being at Mount Athos, using The Nomocanon in Fourteen Titles, Synopsis of Stefan the Efesian, Nomocanon of John Scholasticus, Ecumenical Councils’ documents, which he modified with the canonical commentaries of Aristinos and John Zonaras, local church meetings, rules of the Holy Fathers, the law of Moses, translation of Prohiron and the Byzantine emperors’ Novellae (most were taken from Justinian’s Novellae). The Nomocanon was completely new compilation of civil and canonical regulations, taken from the Byzantine sources, but completed and reformed by St. Sava to function properly in Serbia. Beside decrees that organized the life of church, there are various norms regarding civil life, most of them were taken from Prohiron. Legal transplants of Roman-Byzantine law became the basis of the Serbian medieval law. The essence of Zakonopravilo was based on Corpus Iuris Civilis.

Stefan Dušan, Emperor of Serbs and Greeks, enacted Dušan’s Code (Serbian: Dušanov Zakonik)[24] in Serbia, in two state congresses: in 1349 in Skopje and in 1354 in Serres. It regulated all social spheres, so it was the second Serbian constitution, after St. Sava’s Nomocanon (Zakonopravilo). The Code was based on Roman-Byzantine law. The legal transplanting is notable with the articles 171 and 172 of Dušan’s Code, which regulated the juridical independence. They were taken from the Byzantine code Basilika (book VII, 1, 16-17).

Hungary

In 1222, Hungarian King Andrew II issued the Golden Bull of 1222.

Saxony

Between 1220 and 1230, a Saxon administrator, Eike von Repgow, composed the Sachsenspiegel, which became the supreme law used in parts of Germany as late as 1900.

Mali Empire

In 1236, Sundiata Keita presented an oral constitution federating the Mali Empire, called the Kouroukan Fouga.

Ethiopia

Meanwhile, around 1240, the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer, ‘Abul Fada’il Ibn al-‘Assal, wrote the Fetha Negest in Arabic. ‘Ibn al-Assal took his laws partly from apostolic writings and Mosaic law, and partly from the former Byzantine codes. There are a few historical records claiming that this law code was translated into Ge’ez and entered Ethiopia around 1450 in the reign of Zara Yaqob. Even so, its first recorded use in the function of a constitution (supreme law of the land) is with Sarsa Dengel beginning in 1563. The Fetha Negest remained the supreme law in Ethiopia until 1931, when a modern-style Constitution was first granted by Emperor Haile Selassie I.

China

In China, the Hongwu Emperor created and refined a document he called Ancestral Injunctions (first published in 1375, revised twice more before his death in 1398). These rules served in a very real sense as a constitution for the Ming Dynasty for the next 250 years.

Sardinia

In 1392 the Carta de Logu was legal code of the Giudicato of Arborea promulgated by the giudicessa Eleanor. It was in force in Sardinia until it was superseded by the code of Charles Felix in April 1827. The Carta was a work of great importance in Sardinian history. It was an organic, coherent, and systematic work of legislation encompassing the civil and penal law.

Modern constitutions

The earliest written constitution still governing a sovereign nation today may be that of San Marino. The Leges Statutae Republicae Sancti Marini was written in Latin and consists of six books. The first book, with 62 articles, establishes councils, courts, various executive officers and the powers assigned to them. The remaining books cover criminal and civil law, judicial procedures and remedies. Written in 1600, the document was based upon the Statuti Comunali (Town Statute) of 1300, itself influenced by the Codex Justinianus, and it remains in force today.

In 1639, the Colony of Connecticut adopted the Fundamental Orders, which is considered the first North American constitution, and is the basis for every new Connecticut constitution since, and is also the reason for Connecticut’s nickname, «the Constitution State». England had two short-lived written Constitutions during Cromwellian rule, known as the Instrument of Government (1653), and Humble Petition and Advice (1657).

Agreements and Constitutions of Laws and Freedoms of the Zaporizian Host can be acknowledged as the first European constitution in a modern sense.[25] It was written in 1710 by Pylyp Orlyk, hetman of the Zaporozhian Host. This «Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk» (as it is widely known) was written to establish a free Zaporozhian-Ukrainian Republic, with the support of Charles XII of Sweden. It is notable in that it established a democratic standard for the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws. This Constitution also limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected Cossack parliament called the General Council. However, Orlyk’s project for an independent Ukrainian State never materialized, and his constitution, written in exile, never went into effect.

Other examples of early European constitutions were the Corsican Constitution of 1755 and the Swedish Constitution of 1772.

All of the British colonies in North America that were to become the 13 original United States, adopted their own constitutions in 1776 and 1777, during the American Revolution (and before the later Articles of Confederation and United States Constitution), with the exceptions of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts adopted its Constitution in 1780, the oldest still-functioning constitution of any U.S. state; while Connecticut and Rhode Island officially continued to operate under their old colonial charters, until they adopted their first state constitutions in 1818 and 1843, respectively.

Enlightenment constitutions

What is sometimes called the «enlightened constitution» model was developed by philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment such as Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke. The model proposed that constitutional governments should be stable, adaptable, accountable, open and should represent the people (i.e. support democracy).[26]

The United States Constitution, ratified June 21, 1788, was influenced by the British constitutional system and the political system of the United Provinces, plus the writings of Polybius, Locke, Montesquieu, and others. The document became a benchmark for republicanism and codified constitutions written thereafter.

Next were the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Constitution of May 3, 1791,[27][28][29] and the French Constitution of September 3, 1791.

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 served as a model for other liberal constitutions of several South-European and Latin American nations like Portuguese Constitution of 1822, constitutions of various Italian states during Carbonari revolts (i.e. in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), or Mexican Constitution of 1824.[30] As a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the absolute monarchy of Denmark lost its personal possession of Norway to another absolute monarchy, Sweden. However the Norwegians managed to infuse a radically democratic and liberal constitution in 1814, adopting many facets from the American constitution and the revolutionary French ones; but maintaining a hereditary monarch limited by the constitution, like the Spanish one. The Serbian revolution initially led to a proclamation of a proto-constitution in 1811; the full-fledged Constitution of Serbia followed few decades later, in 1835.

Principles of constitutional design

After tribal people first began to live in cities and establish nations, many of these functioned according to unwritten customs, while some developed autocratic, even tyrannical monarchs, who ruled by decree, or mere personal whim. Such rule led some thinkers to take the position that what mattered was not the design of governmental institutions and operations, as much as the character of the rulers. This view can be seen in Plato, who called for rule by «philosopher-kings.»[31] Later writers, such as Aristotle, Cicero and Plutarch, would examine designs for government from a legal and historical standpoint.

The Renaissance brought a series of political philosophers who wrote implied criticisms of the practices of monarchs and sought to identify principles of constitutional design that would be likely to yield more effective and just governance from their viewpoints. This began with revival of the Roman law of nations concept[32] and its application to the relations among nations, and they sought to establish customary «laws of war and peace»[33] to ameliorate wars and make them less likely. This led to considerations of what authority monarchs or other officials have and don’t have, from where that authority derives, and the remedies for the abuse of such authority.[34]

A seminal juncture in this line of discourse arose in England from the Civil War, the Cromwellian Protectorate, the writings of Thomas Hobbes, Samuel Rutherford, the Levellers, John Milton, and James Harrington, leading to the debate between Robert Filmer, arguing for the divine right of monarchs, on the one side, and on the other, Henry Neville, James Tyrrell, Algernon Sidney, and John Locke. What arose from the latter was a concept of government being erected on the foundations of first, a state of nature governed by natural laws, then a state of society, established by a social contract or compact, which bring underlying natural or social laws, before governments are formally established on them as foundations.

Along the way several writers examined how the design of government was important, even if the government were headed by a monarch. They also classified various historical examples of governmental designs, typically into democracies, aristocracies, or monarchies, and considered how just and effective each tended to be and why, and how the advantages of each might be obtained by combining elements of each into a more complex design that balanced competing tendencies. Some, such as Montesquieu, also examined how the functions of government, such as legislative, executive, and judicial, might appropriately be separated into branches. The prevailing theme among these writers was that the design of constitutions is not completely arbitrary or a matter of taste. They generally held that there are underlying principles of design that constrain all constitutions for every polity or organization. Each built on the ideas of those before concerning what those principles might be.

The later writings of Orestes Brownson[35] would try to explain what constitutional designers were trying to do. According to Brownson there are, in a sense, three «constitutions» involved: The first the constitution of nature that includes all of what was called «natural law.» The second is the constitution of society, an unwritten and commonly understood set of rules for the society formed by a social contract before it establishes a government, by which it establishes the third, a constitution of government. The second would include such elements as the making of decisions by public conventions called by public notice and conducted by established rules of procedure. Each constitution must be consistent with, and derive its authority from, the ones before it, as well as from a historical act of society formation or constitutional ratification. Brownson argued that a state is a society with effective dominion over a well-defined territory, that consent to a well-designed constitution of government arises from presence on that territory, and that it is possible for provisions of a written constitution of government to be «unconstitutional» if they are inconsistent with the constitutions of nature or society. Brownson argued that it is not ratification alone that makes a written constitution of government legitimate, but that it must also be competently designed and applied.

Other writers[36] have argued that such considerations apply not only to all national constitutions of government, but also to the constitutions of private organizations, that it is not an accident that the constitutions that tend to satisfy their members contain certain elements, as a minimum, or that their provisions tend to become very similar as they are amended after experience with their use. Provisions that give rise to certain kinds of questions are seen to need additional provisions for how to resolve those questions, and provisions that offer no course of action may best be omitted and left to policy decisions. Provisions that conflict with what Brownson and others can discern are the underlying «constitutions» of nature and society tend to be difficult or impossible to execute, or to lead to unresolvable disputes.

Constitutional design has been treated as a kind of metagame in which play consists of finding the best design and provisions for a written constitution that will be the rules for the game of government, and that will be most likely to optimize a balance of the utilities of justice, liberty, and security. An example is the metagame Nomic.[37]

Governmental constitutions

Most commonly, the term constitution refers to a set of rules and principles that define the nature and extent of government. Most constitutions seek to regulate the relationship between institutions of the state, in a basic sense the relationship between the executive, legislature and the judiciary, but also the relationship of institutions within those branches. For example, executive branches can be divided into a head of government, government departments/ministries, executive agencies and a civil service/bureaucracy. Most constitutions also attempt to define the relationship between individuals and the state, and to establish the broad rights of individual citizens. It is thus the most basic law of a territory from which all the other laws and rules are hierarchically derived; in some territories it is in fact called «Basic Law».

Key features

The following are features of democratic constitutions that have been identified by political scientists to exist, in one form or another, in virtually all national constitutions.

Codification

A fundamental classification is codification or lack of codification. A codified constitution is one that is contained in a single document, which is the single source of constitutional law in a state. An uncodified constitution is one that is not contained in a single document, consisting of several different sources, which may be written or unwritten.

Codified constitution

Most states in the world have codified constitutions.

Codified constitutions are often the product of some dramatic political change, such as a revolution. The process by which a country adopts a constitution is closely tied to the historical and political context driving this fundamental change. The legitimacy (and often the longevity) of codified constitutions has often been tied to the process by which they are initially adopted.

States that have codified constitutions normally give the constitution supremacy over ordinary statute law. That is, if there is any conflict between a legal statute and the codified constitution, all or part of the statute can be declared ultra vires by a court, and struck down as unconstitutional. In addition, exceptional procedures are often required to amend a constitution. These procedures may include: convocation of a special constituent assembly or constitutional convention, requiring a supermajority of legislators’ votes, the consent of regional legislatures, a referendum process, and other procedures that make amending a constitution more difficult than passing a simple law.

Constitutions may also provide that their most basic principles can never be abolished, even by amendment. In case a formally valid amendment of a constitution infringes these principles protected against any amendment, it may constitute a so-called unconstitutional constitutional law.

Codified constitutions normally consist of a ceremonial preamble, which sets forth the goals of the state and the motivation for the constitution, and several articles containing the substantive provisions. The preamble, which is omitted in some constitutions, may contain a reference to God and/or to fundamental values of the state such as liberty, democracy or human rights.

Uncodified constitution

Main article: Uncodified constitution

As of 2010 at least three states have uncodified constitutions: Israel, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Uncodified constitutions (also known as unwritten constitutions) are the product of an «evolution» of laws and conventions over centuries. By contrast to codified constitutions, in the Westminster tradition that originated in England, uncodified constitutions include written sources: e.g. constitutional statutes enacted by the Parliament (House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975, Northern Ireland Act 1998, Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, European Communities Act 1972 and Human Rights Act 1998); and also unwritten sources: constitutional conventions, observation of precedents, royal prerogatives, custom and tradition, such as always holding the General Election on Thursdays; together these constitute the British constitutional law. In the days of the British Empire, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council acted as the constitutional court for many of the British colonies such as Canada and Australia which had federal constitutions.

Elements of constitutional law in states with uncodified constitutions can be entrenched; for example, sections of the Electoral Act 1993 of New Zealand relating to the maximum term of parliament and how elections are held require a three-quarter majority in the House of Representatives or a simple majority in a referendum to be amended or repealed.

Written versus unwritten / codified versus uncodified

The term written constitution is used to describe a constitution that is entirely written, which by definition includes every codified constitution; but not all constitutions based entirely on written documents are codified.

Some constitutions are largely, but not wholly, codified. For example, in the Constitution of Australia, most of its fundamental political principles and regulations concerning the relationship between branches of government, and concerning the government and the individual are codified in a single document, the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia. However, the presence of statutes with constitutional significance, namely the Statute of Westminster, as adopted by the Commonwealth in the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942, and the Australia Act 1986 means that Australia’s constitution is not contained in a single constitutional document. The Constitution of Canada, which evolved from the British North America Acts until severed from nominal British control by the Canada Act 1982 (analogous to the Australia Act 1986), is a similar example. Canada’s constitution consists of almost 30 different statutes

The terms written constitution and codified constitution are often used interchangeably, as are unwritten constitution and uncodified constitution, although this usage is technically inaccurate. Strictly speaking, unwritten constitution is never an accurate synonym for uncodified constitution, because all modern democratic constitutions mainly comprise written sources, even if they have no different legal status than ordinary statutes. Another, correct, term used is formal (or formal written) constitution, for example in the following context: «The United Kingdom has no formal [written] constitution» (which does not preclude a constitution based on documents but not codified).

Entrenchment

The U.S. Constitution

The presence or lack of entrenchment is a fundamental feature of constitutions. An entrenched constitution cannot be altered in any way by a legislature as part of its normal business concerning ordinary statutory laws, but can only be amended by a different and more onerous procedure. There may be a requirement for a special body to be set up, or the proportion of favourable votes of members of existing legislative bodies may be required to be higher to pass a constitutional amendment than for statutes. The entrenched clauses of a constitution can create different degrees of entrenchment, ranging from simply excluding constitutional amendment from the normal business of a legislature, to making certain amendments either more difficult than normal modifications, or forbidden under any circumstances.

Entrenchment is an inherent feature in most codified constitutions. A codified constitution will incorporate the rules which must be followed for the constitution itself to be changed.

The US constitution is an example of an entrenched constitution, and the UK constitution is an example of a constitution that is not entrenched (or codified). In some states the text of the constitution may be changed; in others the original text is not changed, and amendments are passed which add to and may override the original text and earlier amendments.

Procedures for constitutional amendment vary between states. In a nation with a federal system of government the approval of a majority of state or provincial legislatures may be required. Alternatively, a national referendum may be required. Details are to be found in the articles on the constitutions of the various nations and federal states in the world.

In constitutions that are not entrenched, no special procedure is required for modification. Lack of entrenchment is a characteristic of uncodified constitutions; the constitution is not recognised with any higher legal status than ordinary statutes. In the UK, for example laws which modify written or unwritten provisions of the constitution are passed on a simple majority in Parliament. No special «constitutional amendment» procedure is required. The principle of parliamentary sovereignty holds that no sovereign parliament may be bound by the acts of its predecessors;[38] and there is no higher authority that can create law which binds Parliament. The sovereign is nominally the head of state with important powers, such as the power to declare war; the uncodified and unwritten constitution removes all these powers in practice.

In practice democratic governments do not use the lack of entrenchment of the constitution to impose the will of the government or abolish all civil rights, as they could in theory do, but the distinction between constitutional and other law is still somewhat arbitrary, usually following historical principles embodied in important past legislation. For example, several British Acts of Parliament such as the Bill of Rights, Human Rights Act and, prior to the creation of Parliament, Magna Carta are regarded as granting fundamental rights and principles which are treated as almost constitutional. Several rights that in another state might be guaranteed by constitution have indeed been abolished or modified by the British parliament in the early 21st century, including the unconditional right to trial by jury, the right to silence without prejudicial inference, permissible detention before a charge is made extended from 24 hours to 42 days, and the right not to be tried twice for the same offence.

Absolutely unmodifiable articles

The strongest level of entrenchment exists in those constitutions that state that some of their most fundamental principles are absolute, i.e. certain articles may not be amended under any circumstances. An amendment of a constitution that is made consistently with that constitution, except that it violates the absolute non-modifiability, can be called an unconstitutional constitutional law. Ultimately it is always possible for a constitution to be overthrown by internal or external force, for example, a revolution (perhaps claiming to be justified by the right to revolution) or invasion.

An example of absolute unmodifiability is the German Federal Constitution. This states in Articles 1 and 20 that the state powers, which derive from the people, must protect human dignity on the basis of human rights, which are directly applicable law binding on all three branches of government, which is a democratic and social federal republic; that legislation must be according to the rule of law; and that the people have the right of resistance as a last resort against any attempt to abolish the constitutional order. Article 79, Section 3 states that these articles cannot be changed, even according to the methods of amendment defined elsewhere in the document.

Another example is the Constitution of Honduras, which has an article stating that the article itself and certain other articles cannot be changed in any circumstances. Article 374 of the Honduras Constitution asserts this unmodifiability, stating, «It is not possible to reform, in any case, the preceding article, the present article, the constitutional articles referring to the form of government, to the national territory, to the presidential period, the prohibition to serve again as President of the Republic, the citizen who has performed under any title in consequence of which she/he cannot be President of the Republic in the subsequent period.»[39] This unmodifiability article played an important role in the 2009 Honduran constitutional crisis.

Distribution of sovereignty

Constitutions also establish where sovereignty is located in the state. There are three basic types of distribution of sovereignty according to the degree of centralisation of power: unitary, federal, and confederal. The distinction is not absolute.

In a unitary state, sovereignty resides in the state itself, and the constitution determines this. The territory of the state may be divided into regions, but they are not sovereign and are subordinate to the state. In the UK, the constitutional doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty dictates than sovereignty is ultimately contained at the centre. Some powers have been devolved to Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales (but not England). Some unitary states (Spain is an example) devolve more and more power to sub-national governments until the state functions in practice much like a federal state.

A federal state has a central structure with at most a small amount of territory mainly containing the institutions of the federal government, and several regions (called states, provinces, etc.) which comprise the territory of the whole state. Sovereignty is divided between the centre and the constituent regions. The constitutions of Canada and the United States establish federal states, with power divided between the federal government and the provinces or states. Each of the regions may in turn have its own constitution (of unitary nature).

A confederal state comprises again several regions, but the central structure has only limited coordinating power, and sovereignty is located in the regions. Confederal constitutions are rare, and there is often dispute to whether so-called «confederal» states are actually federal.

To some extent a group of states which do not constitute a federation as such may by treaties and accords give up parts of their sovereignty to a supranational entity. For example the countries comprising the European Union have agreed to abide by some Union-wide measures which restrict their absolute sovereignty in some ways, e.g., the use of the metric system of measurement instead of national units previously used.

Separation of powers

Constitutions usually explicitly divide power between various branches of government. The standard model, described by the Baron de Montesquieu, involves three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial. Some constitutions include additional branches, such as an auditory branch. Constitutions vary extensively as to the degree of separation of powers between these branches.

Lines of accountability

In presidential and semi-presidential systems of government, department secretaries/ministers are accountable to the president, who has patronage powers to appoint and dismiss ministers. The president is accountable to the people in an election.

In parliamentary systems, ministers are accountable to Parliament, but it is the prime minister who appoints and dismisses them. In turn the prime minister will resign if the government loses the confidence of the parliament (or a part of it). Confidence can be lost if the government loses a vote of no confidence or, depending on the country, loses a particularly important vote in parliament such as vote on the budget. When a government loses confidence it stays in office until a new government is formed; something which normally but not necessarily required the holding of a general election.

State of emergency

Many constitutions allow the declaration under exceptional circumstances of some form of state of emergency during which some rights and guarantees are suspended. This deliberate loophole can be and has been abused to allow a government to suppress dissent without regard for human rights—see the article on state of emergency.

Façade constitutions

Italian political theorist Giovanni Sartori noted the existence of national constitutions which are a façade for authoritarian sources of power. While such documents may express respect for human rights or establish an independent judiciary, they may be ignored when the government feels threatened, or never put into practice. An extreme example was the Constitution of the Soviet Union that on paper supported freedom of assembly and freedom of speech; however, citizens who transgressed unwritten limits were summarily imprisoned. The example demonstrates that the protections and benefits of a constitution are ultimately provided not through its written terms but through deference by government and society to its principles. A constitution may change from being real to a façade and back again as democratic and autocratic governments succeed each other.

The constitution of the United States, being the first document of its type, necessarily had many unforeseen shortcomings which had to be patched through amendments, but has generally been honored and a powerful structure, and no dictatorship has been able to take hold; the constitution of Argentina written many years later in 1853 building on many years of experience of the US constitution was arguably a better document, but did not prevent a succession of dictatorial governments from ignoring it—a state of emergency was declared 52 times to bypass constitutional guarantees.[40]

Constitutional courts

Constitutions are often, but by no means always, protected by a legal body whose job it is to interpret those constitutions and, where applicable, declare void executive and legislative acts which infringe the constitution. In some countries, such as Germany, this function is carried out by a dedicated constitutional court which performs this (and only this) function. In other countries, such as Ireland, the ordinary courts may perform this function in addition to their other responsibilities. While elsewhere, like in the United Kingdom, the concept of declaring an act to be unconstitutional does not exist.

A constitutional violation is an action or legislative act that is judged by a constitutional court to be contrary to the constitution, that is, unconstitutional. An example of constitutional violation by the executive could be a public office holder who acts outside the powers granted to that office by a constitution. An example of constitutional violation by the legislature is an attempt to pass a law that would contradict the constitution, without first going through the proper constitutional amendment process.

Some countries, mainly those with uncodified constitutions, have no such courts at all. For example the United Kingdom has traditionally operated under the principle of parliamentary sovereignty under which the laws passed by United Kingdom Parliament could not be questioned by the courts.

See also

- Apostolic constitution (a class of Roman Catholic Church documents)

- Constitution of the Roman Republic

- Constitutional court

- Constitutional economics

- Constitutionalism

- Corporate constitution

- Judicial activism

- Judicial restraint

- Judicial review

- Rule of law

- Rule according to higher law

Judicial philosophies of constitutional interpretation (note: generally specific to United States constitutional law)

- List of national constitutions

- Originalism

- Strict constructionism

- Textualism

- Proposed European Union constitution

- Treaty of Lisbon (adopts same changes, but without constitutional name)

- United Nations Charter

References

- ^ The New Oxford American Dictionary, Second Edn., Erin McKean (editor), 2051 pages, May 2005, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517077-6.

- ^ Pylee, M.V. (1997). India’s Constitution. S. Chand & Co.. pp. 3. ISBN 812190403X.

- ^ Sarkar, Siuli. Public Administration In India. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.. p. 363. ISBN 9788120339798. http://books.google.com/books?id=smahlYxg-8YC&pg=PA363.

- ^ «Constitution of India». Ministry of Law and Justice of India. July, 2008. http://indiacode.nic.in/coiweb/welcome.html. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ «National Constitution Center». Independence Hall Association. http://www.ushistory.org/tour/tour_ncc.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ The historical and institutional context of Roman law, George Mousourakis, 2003, p. 243

- ^ Gordon, Scott (1999). Controlling the State: Constitutionalism from Ancient Athens to Today. Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0674169875.

- ^ See:

- Reuven Firestone, Jihād: the origin of holy war in Islam (1999) p. 118;

- «Muhammad», Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Watt. Muhammad at Medina and R. B. Serjeant «The Constitution of Medina.» Islamic Quarterly 8 (1964) p.4.

- ^ R. B. Serjeant, The Sunnah Jami’ah, pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrim of Yathrib: Analysis and translation of the documents comprised in the so-called «Constitution of Medina.» Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 41, No. 1. 1978), page 4.

- ^ Watt. Muhammad at Medina. pp. 227-228 Watt argues that the initial agreement was shortly after the hijra and the document was amended at a later date specifically after the battle of Badr (AH [anno hijra] 2, = AD 624). Serjeant argues that the constitution is in fact 8 different treaties which can be dated according to events as they transpired in Medina with the first treaty being written shortly after Muhammad’s arrival. R. B. Serjeant. «The Sunnah Jâmi’ah, Pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrîm of Yathrib: Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the so called ‘Constitution of Medina’.» in The Life of Muhammad: The Formation of the Classical Islamic World: Volume iv. Ed. Uri Rubin. Brookfield: Ashgate, 1998, p. 151 and see same article in BSOAS 41 (1978): 18 ff. See also Caetani. Annali dell’Islam, Volume I. Milano: Hoepli, 1905, p. 393. Julius Wellhausen. Skizzen und Vorabeiten, IV, Berlin: Reimer, 1889, p 82f who argue that the document is a single treaty agreed upon shortly after the hijra. Wellhausen argues that it belongs to the first year of Muhammad’s residence in Medina, before the battle of Badr in 2/624. Wellhausen bases this judgement on three considerations; first Muhammad is very diffident about his own position, he accepts the Pagan tribes within the Umma, and maintains the Jewish clans as clients of the Ansars see Wellhausen, Excursus, p. 158. Even Moshe Gil a skeptic of Islamic history argues that it was written within 5 months of Muhammad’s arrival in Medina. Moshe Gil. «The Constitution of Medina: A Reconsideration.» Israel Oriental Studies 4 (1974): p. 45.

- ^ a b Tooker E (1990). «The United States Constitution and the Iroquois League». In Clifton JA. The Invented Indian: cultural fictions and government policies. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A: Transaction Publishers. pp. 107–128. ISBN 1-56000-745-1.

- ^ Grindle, D (1992). «Iroquois political theory and the roots of American democracy». In Lyons O. Exiled in the land of the free: democracy, Indian nations, and the U. S. Constitution. Santa Fe, N.M: Clear Light Publishers. ISBN 0-940666-15-4.

- ^ Johansen, Bruce E.; Grinde, Donald A. (1991). Exemplar of liberty: native America and the evolution of democracy. [Los Angeles]: American Indian Studies Center, University of California, Los Angeles. ISBN 0-935626-35-2.

- ^ Armstrong, VI (1971). I Have Spoken: American History Through the Voices of the Indians. Swallow Press. p. 14. ISBN 0804005303.

- ^ «H. Con. Res. 331, October 21, 1988». United States Senate. http://www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/hconres331.pdf. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ^ Shannon, TJ (2000). Indians and Colonists at the Crossroads of Empire: The Albany Congress of 1754. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0801488184.

- ^ Rakove, J (2005-11-07). «Did the Founding Fathers Really Get Many of Their Ideas of Liberty from the Iroquois?». George Mason University. http://hnn.us/articles/12974.html. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ^ Jennings F (1988). Empire of fortune: crown, colonies, and tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York: Norton. pp. 259n15. ISBN 0-393-30640-2.

- ^ Snow DR (1996). The Iroquois (The Peoples of America Series). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 154. ISBN 1-55786-938-3.

- ^ http://books.google.se/books?id=QDFVUDmAIqIC&pg=PA118

- ^ http://www.search.com/reference/Nomocanon

- ^ http://www.alanwatson.org/sr/petarzoric.pdf

- ^ http://www.dusanov-zakonik.com/indexe.html

- ^ Pylyp Orlyk Constitution, European commission for democracy through law (Venice Commission) The Constitutional Heritage of Europe. Montpellier, 22–23 November 1996.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/134169/constitution

- ^ Blaustein, Albert (January 1993). Constitutions of the World. Fred B. Rothman & Company. ISBN 9780837703626. http://books.google.com/?id=2xCMVAFyGi8C&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15&dq=May+second+constitution+1791.

- ^ Isaac Kramnick, Introduction, Madison, James (November 1987). The Federalist Papers. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044495-5. http://books.google.com/?id=WSzKOORzyQ4C&pg=PA13&lpg=PA13&dq=May+second+oldest+constitution.

- ^ «The first European country to follow the U.S. example was Poland in 1791.» John Markoff, Waves of Democracy, 1996, ISBN 0-8039-9019-7, p.121.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). A History of Spain and Portugal: Eighteenth Century to Franco. 2. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 432–433. ISBN 9780299062705. http://libro.uca.edu/payne2/spainport2.htm. «The Spanish pattern of conspiracy and revolt by liberal army officers … was emulated in both Portugal and Italy. In the wake of Riego’s successful rebellion, the first and only pronunciamiento in Italian history was carried out by liberal officers in the kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The Spanish-style military conspiracy also helped to inspire the beginning of the Russian revolutionary movement with the revolt of the Decembrist army officers in 1825. Italian liberalism in 1820-1821 relied on junior officers and the provincial middle classes, essentially the same social base as in Spain. It even used a Hispanized political vocabulary, for it was led by giunte (juntas), appointed local capi politici (jefes políticos), used the terms of liberali and servili (emulating the Spanish word serviles applied to supporters of absolutism), and in the end talked of resisting by means of a guerrilla. For both Portuguese and Italian liberals of these years, the Spanish constitution of 1812 remained the standard document of reference.»

- ^ Aristotle, by Francesco Hayez

- ^ Relectiones, Franciscus de Victoria (lect. 1532, first pub. 1557).

- ^ The Law of War and Peace, Hugo Grotius (1625)

- ^ Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos (Defense of Liberty Against Tyrants), «Junius Brutus» (Orig. Fr. 1581, Eng. tr. 1622, 1688)

- ^ The American Republic: its Constitution, Tendencies, and Destiny, O. A. Brownson (1866)

- ^ Principles of Constitutional Design, Donald S. Lutz (2006) ISBN 0-521-86168-3

- ^ The Paradox of Self-Amendment, byPeter Suber (1990) ISBN 0-8204-1212-0

- ^ UK principle: no Parliament is bound by the acts of its predecessors

- ^ Honduran Constitution «Republic of Honduras: Political Constitution of 1982 through 2005 reforms; Article 374» (in Spanish). Political Database of the Americas (Georgetown University). http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Honduras/hond05.html Honduran Constitution

- ^ State of emergency in Argentina and other Spanish-speaking countries (in Spanish)

External links

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas Constitutionalism

- Constitutional Law, «Constitutions, bibliography, links»

- International Constitutional Law: English translations of various national constitutions

- constitutions of countries of the European Union

- United Nations Rule of Law: Constitution-making, on the relationship between constitution-making, the rule of law and the United Nations.

- Democracy in Ancient India by Steve Muhlberger of Nipissing University

- Report on the British constitution and proposed European constitution by Professor John McEldowney, University of Warwick Submitted as written evidence to House of Lords Select Committee on Constitution, published to the public on 15 October 2003.

The House of

Commons is the only chamber in the British Parliament which is

elected at General Elections. British subjects and citizens can

vote provided they are 18 and over, resident in the UK, registered

in the annual register of electors and not subject to any

disqualifications. The UK is divided into 659 electoral districts,

called constituencies of approximately equal population and each

const, elects the member of the HC. No person can be elected except

under the name of the party, and there is little chance except as

the candidate backed by either the Labor or the Conservative party.

In every constituency each of the 2 parties has a local

organization, which chooses the candidate, and then helps him to

conduct his local campaign, in a British election the candidate who

wins the most votes in elected, even if he doesn’t get as many as

the combined votes of the other candidates. The winner takes it

all. This is known as notorious majority electoral system that is

often criticized for being unfair to smaller parties that have very

little chance to send their candidate to the Commons. It is often

argued that the British system of elections is so unfair that it

ought to be changed, by the introduction of a form of proportional

representation. It aims to give each party a proportion of seats in

Parliament corresponding to the proportion of votes it receives at

the election. As soon as the results of a general elections are

known, it is clear which party will form the government. The leader

of the majority party becomes Prime Minister and the new House of

Commons meets. The chief officer of the HC is the Speaker. He is

elected by the House at the beginning of each parliament. His chief

function is to preside over the House in the debate. The Speaker

must not belong to any party. G Brown

11.British government

The party

which, wins most seats (but not necessarily most votes) at a

general election, or which has the support of a majority of the

members in the House of Commons, usually forms the. government.

On occasions when no party succeeds in winning an overall

majority of seats, a minority Government or a coalition may be

formed. The leader of the majority party is appointed Prime Minster

by the Sovereign, and all other ministers are appointed by the Queen

on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. The majority of

ministers are members of the Commons, although the Government is

represented by some ministers in the Lords Since the late 19 century

the Prime Minister has normally been the leader of the party with a

majority in the House of Commons. The monarch’s role in government

is virtually limited to acting on the advice of ministers.

The Prime

Minister informs the Queen of the general business of the Government,

presides over the Cabinet, and is responsible for the allocation of

functions among ministers, recommends to the Queen a number of

important appointments. Ministers in charge of Government

departments, who are usually in the Cabinet, are known as

‘Secretaries of State or ‘Ministers’, or may have a traditional

title, as in the case of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the

Postmaster General, the President of the Board of Trade. All these

are known as departmental ministers. The Lord Chancellor (the

Speaker of the House of Lords) holds a special position, being a

minister with departmental functions and also head of the judiciary

in England and Hales.

Ministers

of State (non-departmental) work with ministers in charge of

departments with responsibility for specific functions, and are

sometimes given courtesy titles which reflect these particular

functions. More than one may work in a department. Junior

ministers (generally Parliamentary Secretaries or Under-Secretaries

of State) share in parliamentary and departmental duties. They may

also be given responsibility directly under the departmental

minister, for specific aspects of the department’s work.

The largest

minority party becomes the official opposition with its own leader

and its own ‘shadow cabinet’ whose members act as spokesmen on

the subjects for which government ministers have responsibility.

The members of any other party support or oppose the Government

according to their party policy being debated at any given time.The

Government has the major share in controlling and arranging the

business of the House. As the initiator of policy, it dictates what

action it wishes Parliament to take.

A modern

British Government consists of over ninety people, of whom about

thirty are heads of departments, and the rest are their assistants.

Until quite recent times all the heads of departments were included

in the Cabinet, but when their number rose some of the less

important heads of departments were oat included in the Cabinet.

The Prime .Minister, decides whom to include.

The Cabinet

is composed of about 20 ministers and nay include departmental and

non-departmental ministers. The prime ministers may make changes in

the size of their Cabinet and may create new ministries or make

other changes.The Cabinet as such is not recognized by any formal

law, and it has no formal powers but only real powers. It takes

the effective decisions about what is to be done. Its major

functions are: the final determination of policies, the supreme

control of government and the coordination of government

departments. More and more power is concentrated in the hands of the

Cabinet, where the decisive role belongs to the Prime Minster, who

in fact determines the general political line of this body. The

Cabinet defends and encourages the activity of monopolies and big

business, does everything to restrain and suppress the working-class

movement. The County Councilor county) is the most important .unit

of local government. The District Councils-for districts.

12.The

20th century witnessed an intensive process of decolonisation of the

British Empire(the last Br. colony Hong Kong was reverted to China

in 1997). A tendency to decolonise grew into a desire to form a

great family, a special union, for economic, cultural & social

reasons. The Commonwealth of Nations, usually known as the

Commonwealth, is a voluntary association of 53 independent sovereign

states, most of which are former British colonies, or dependencies

of these colonies (the exceptions being the United Kingdom itself

and Mozambique). The Commonwealth is an international organization

through which countries with diverse social, political,

and-economic backgrounds co¬operate within a framework of common

values and goals, outlined in the Singapore Declaration. These

include the promotion of democracy, human rights, good governance,

the rule of law, individual liberty, egalitarianism. free trade,

multilateralism, and world peace.Queen Elizabeth II is the Head of

the Commonwealth, recognized by each state, and as such is the symbol

of the free association of the organization’s members. This

position, however, does not imply political power over Commonwealth

member states. In practice, the Queen heads the Commonwealth in a

symbolic capacity, and it is the Commonwealth Secretary-General who

is the chief executive of the organization. The Commonwealth is

not a political union, and does not allow the United Kingdom to

exercise any power over the affairs of the organization’s other

members. Elizabeth II is also the Head of State, separately, of

sixteen members of the Commonwealth, called Commonwealth realms. As

each realm is an independent kingdom, Elizabeth II, as monarch,

holds a distinct jjtk for each.

Every four

years the Commonwealth’s members celebrate the Commonwealth Games,

the world’s second-largest multi-sport event after the Olympic

Games. Commonwealth Dayton the 2nd Monday in March. The Commonwealth

secretariat provides the central organization for consultation &

co-operation among member states. Established in London in 1965,

headed by the heads of Government & financed by member

Governments, the Secretariat is responsible to Commonwealth

Governments collectively. The Secretariat promotes consultation,

disseminates info on matters of common concern, & organizes

meetings & coferences. Membership criteria: be fully sovereign

states; recognise the monarch of the Commonwealth realms as

the Head of the commonwealth; accept the English language as the

means of Commonwealth communication; respect the wishes of the

general population vis-a-vis Commonwealth membership The

Commonwealth’s objectives were first outlined in the 1971 Singapore

Declaration, which committed the Commonwealth to the institution of

world peace: promotion of the pursuit of equality and opposition

to racism; the fight against poverty, ignorance, and disease; and

free trade. To these were added opposition to discrimination on the

basis of gender, and environmental attainability. These objectives

were reinforced by the Harare Declaration in 1991.

The

Comnonwealth is also useful as an international organisation that

represents significant cultural and historical links between wealthy

first-world countries and poorer nations with diverse social and

religious backgrounds.

13.Today

Britain is no longer the leading industrial nation of the world,

which it was during the last century. Today Britain is 5th in size

of its gross domestic product(GDP).Britain’s share in world trade is

about 6%, which means that she is also the 5th largest trading

nation in the world. Trade with the countries of the European Union,

Commonwealth countries.British economy based on private enterprise.

The policy of the government is aimed at encouraging & expanding

the private sector. Result: 751 of the economy is controlled by

the private sector which employs 3/4of the labour force. Less than

2% of working population is engaged in agriculture. Due to

large-scale mechanization productivity in agriculture is very high:

it supplies nearly 2/3 of the countries food. The general location of

industry: 80% Of industrial production –England. In Wales,

Scotland & Northem Ireland level of industry is lower than in

England. This gap between England & the outlying regions

increased because of the decline of the traditional industries, which

are heavily concentrating in Wales, N.Ireland, Scotland. GB may be

divided into 8 economic regions: 1) the South industrial &

agricultural region 2}the Midlands 3)Lancashire 4)Yorkshire 5)the

North 6)Scotland 7) Wales & Northern Ireland

THE SOUTH

ECONOMIC REGION The most: important region in terms of industry &

agriculture. Includes: all the South of England, both the South-East

& the South-West. London -centre of everything (called the

London City Region). Clothing, furniture-making & jewellery.

London’s industries: electrical engineering, instrument production,

radio engineering, aircraft production, the motor-car industry,

London -centre of the service industries, tourism.

OXFORD:

educational centre; a large motor works were built in its suburb.

CAMBRIDGE: its industries connected with electronics & printing.

LUTON: major centre of car production. The Thames valley is an area

of concentration of electronic engineering/ microelectronics. The

South -major agricultural region of GB.

14.The

problem of Northern Ireland is closely connected with religion

because the Irish people can be divided into 2 religious groups:

Catholic and Protestants. At the same time it as clear that the

lighting between these 2 groups is closely connected with the

colonial past, in 1169 Henry 2 of England started an invasion of

Ireland. Although a large part of Ireland came under the control

of the invaders, there wasn’t much direct control from England

during the middle ages. In the 16th century Henry 6 of England

quarreled with Rome and declared himself Head of the Anglican church,

which was a protestant church. Ireland remained Catholic, and

didn’t accept the change. Henry 8 tried to force them to become

Anglican. He also punished them by taking most of their land. This

policy was continued by Elizabeth I. But the Irish Catholics never

gave up their struggle for independence and their rights. At the

end of the 18th century there was a mass rising against the English

colonizers which was crushed by the English army and in 1801 a

forced union was established with Britain. All through the 19th

century the «Irish question» remained in the centre of

British polities. After a long and bitter struggle the southern part

of Ireland finally became a free State in l921. Ulster where the

protestants were in majority remained part of the UK. The Irish

free State declared itself a Republic in 1949 and is known as the

Irish republic of Eire. It is completely independent and its

capital is Dublin. Northern Ireland had its own Parliament at

Stormont in Belfast and government which was responsible for its

province’s life. But from the beginning the parliament was in the

hands of Protestants while the Catholics didn’t have equal rights

with the Protestants. In 1969 .conflict started between these 2

groups and so the British government closed the local parliamentand

sent in die British army to keep the peace. But there were no peace.

On he Catholic side is the Irish Republic Army which wants to

achieve a united reland by terrorism and bombings. On the Protestant

side there are also secret terrorist organizations.

The

Northern Ireland Assembly of 108 members was restored in 1998.

Elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly were held in November

2003.However many difficulties still exist’ to make this local

parliament a workable body because of the confrontation between the

parties representing the Protestant and Catholic communities. The

Northern Ireland Assembly was established as part of the Belfast

Agreement and meets in Parliament Buildings. The Assembly is the

prime source of authority for all devolved responsibilities and has

full legislative and executive authority. Elections to the Northern

Ireland Assembly took place on the 7th March 2007 and the Northern

Ireland Assembly was restored on the 8th of May 2007.

15.Americans

seem strangely oblivious to historic developments in Europe these

days that could mean a profound change in this country’s relations

with Europe as a whole, and with Britain in particular. The process

of European integration is reaching a new stage, with not only

Economic and Monetary Union but also the beginning of a common

security and defense policy. No one seriously questions the wisdom

and enlightened statesmanship of the U.S. policy that has supported

European integration over many decades. But the contemporary phase of

that process is bringing us into uncharted territory. It raises major

questions about the future cohesion of the Atlantic Alliance and

about the future of the «special relationship» that the

United States has long enjoyed with Britain.The Anglo-American

tradition embodies a very special conception of political and

economic liberty, as well as a certain seriousness about

international security and, indeed, about the moral unity of the

West. These Anglo-American values as thoroughly vindicated by history

and, therefore, worthy of the most vigorous defense.

Since the

Eisenhower era, the United States has been urging Britain into

Europe, initially to strengthen the resolve of the Europeans as Cold

Warriors and more recently out of habit and to be a force for good

government in Europe. Today, all polls in Britain show that about 70%

of people in the U.K. do not want to go farther into the EU, although

about half believe that the country may ultimately do so anyway.

EUROPE helped bring down two of Britain’s recent prime ministers,

Margaret Thatcher and John Major. But at least they were casualties

of weighty conflicts over their country’s future in the European

Union (EU). On June 4th Gordon Brown may be mortally wounded by

nothing grander than election results for the European Parliament.The

Commonwealth of Nations, usually known as the Commonwealth, is an

intergovernmental organisation of fifty-three independent member

states. Most of them were formerly parts of the British Empire. They

co-operate within a framework of common values and goals, as outlined

in the Singapore Declaration. These include the promotion of

democracy, human rights, good governance, the rule of law, individual

liberty, egalitarianism, free trade, multilateralism, and world

peace. The Commonwealth is not a political union, but an

intergovernmental organisation through which countries with diverse

social, political, and economic backgrounds are regarded as equal in

status. Its activities are carried out through the permanent

Commonwealth Secretariat, headed by the Secretary-General; biennial

Meetings between Commonwealth Heads of Government; and the

Commonwealth Foundation, which facilitates activities of

non-governmental organisations in the so-called ‘Commonwealth

Family’. The symbol of this free association is the Head of the

Commonwealth, which is a ceremonial position currently held by Queen

Elizabeth II. Elizabeth II is also the monarch, separately, of

sixteen members of the Commonwealth, informally called the

Commonwealth realms. As each realm is an independent kingdom, the

Queen, as monarch, holds a distinct title for each, though, by a

Prime Ministers’ Conference in 1952, all include the style Head of

the Commonwealth at the end; for example: Elizabeth the Second, by

the Grace of God, Queen of Australia and of Her other Realms and

Territories, Head of the Commonwealth. Beyond the realms, the

majority of the members of the Commonwealth have separate heads of

state: thirty-two members are republics, and five members have

distinct monarchs: the Sultan of Brunei; the King of Lesotho; the

Yang di-Pertuan Agong (or King) of Malaysia; the King of Swaziland;

and the King of Tonga.

Working with

Belarus

The UK is a

leading member of the European Union. The 27 current member states of

the EU have agreed to work together on issues of common interest,

where collective and co-ordinated initiatives can be more effective

than individual state action. UK relations with Belarus are conducted

within the framework of the EU Common Position towards Belarus.

The UK also

enjoys bilateral co-operation with Belarus in a range of areas.

Following an intense period of negotiations, the two countries

concluded an Agreement on conditions for the recuperation of

Belarusian minors in the UK. The Agreement, which came into force on

May 22, now makes it possible for British charitable organizations to

resume their valuable work.

British

Ambassador Nigel Gould-Davies said: “I am delighted that we have

reached this important agreement. This will directly benefit

thousands of Belarusian children. The Belarusian authorities have

indicated their readiness to discuss additional issues, in