If you happen to be in Moscow in early September, you have a chance to see one of the most famous reenactments in the world — the Battle of Borodino.

The Battle of Borodino, fought on September 7, 1812, was the largest single-day action of the French invasion of Russia. Napoleon’s plans to defeat the Russian army were ruined as Russians demonstrated bravery and military skills.

There’s still some historical dispute about who won the battle of Borodino. On the one hand, Kutuzov ordered his army to retreat and leave Moscow. On the other hand, this battle became the turning point in the war, and the French army was badly weakened for the first time: 30,000 French soldiers were killed or wounded. “Of the fifty battles I have fought, the most terrible was that before Moscow,” Napoleon later said.

In memory of the Battle of Borodino the Borodino Museum of History was established. On the territory of the museum a reenactment of the Battle of Borodino takes place on the first weekend of September. About two thousand common people wearing the uniforms of the Russian and French armies of 1812 recreate the scenario of the Battle of Borodino in every detail. During the event there are lines of infantry, artillery, grenadiers, hussars, dragoons on the battlefield. —– and flame from the batteries of cannon go up, cavalry runs across the battlefield amid the fire. They give viewers the atmosphere of the battle reproducing everything: from the colour, shape and material of the uniforms to the weapons and musical instruments as well as the music, language and customs.

We can imagine how it was thanks to history lovers from all over Russia. They study historical literature and make costumes, weapons, flags, drums and other things to take a step back in time and to live like people lived some two hundred years ago. They do it not because it can bring them a lot of money or fame, but mostly because they believe it’s a right thing to do. They remember history and treat it not like a few dull paragraphs in a school textbook but as live moments of the past that influenced the future. To get in the ‘role’ they arrive at Borodino several days in advance and set a field camp. For this time they completely give up any modern things and habits.

I have gone to Borodino for many years, and every time it’s like a first time — so exiting, so colourful and breathtaking! I am always impressed by the things going on in front of my eyes — hundreds of soldiers loading their guns, screaming “Attack!” and riding horses just in a few metres from my nose! It’s a moment of history when we, modern people, are paying tribute to our ancestors, and show that we remember their acts of bravery. I’m truly amazed by people dedicating their time and talents to battle reproduction and I’m sure they’re doing the right thing. They show that bravery, honesty and courage still exist and are valued. As someone said, if you do not know your history, you have no future. I leave Borodino every time to come to the battlefield next time!

1) Autumn is the best time to see Moscow and its suburbs.

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

2) Napoleon’s army left the battlefield as a lot of its soldiers had been killed.

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

3) The Battle of Borodino is recreated on the territory of the Borodino Museum of History in late autumn.

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

4) Russian and French are spoken in Borodino on the day of the reenactment of the battle.

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

5) The Battle of Borodino is recreated by Russian and French actors.

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

6) Russian and French are spoken in Borodino on the day of the reenactment of the battle.

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

7) The Battle of Borodino is recreated by Russian and French actors.

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

1. True

2. False

3. Not stated

1) – Not Stated

2) – False

3) – False

4) – True

5) – False

6) – True

7) – Not Stated

Infobox Military Conflict

conflict=Battle of Borodino

partof=French invasion of Russia (1812)

caption=An unnamed painting of the Battle of Borodino by an unspecified artist

date=

September 7, 1812

place=Borodino, Russia

result= French victory

combatant1=

combatant2= [Note that although no official flag existed during this period, the tricolour represents the officer sash colours and the Double Eagle represents the Tsar’s official state symbol]

commander1=

commander2=

strength1=130,000 men, 587 Guns [Richard K. Riehn, «Napoleon’s Russian Campaign», John Wiley & Sons, 2005, p. 479.]

strength2=120,000 men, 640 Guns

casualties1=35,000 dead, wounded and captured [The book ‘Napoleon’ by Herman Lindqvist. Page 368, chapter 20, ‘The battle of Borodino, the bloodiest of them all’ ]

casualties2=~44,000 dead, wounded and captured [Smith, p. 392]

The Battle of Borodino ( _ru. Бородинская битва «Borodinskaja bitva», _fr. Bataille de la Moskowa), fought on September 7, 1812 [August 26 in the Julian calendar then used in Russia] , was the largest and bloodiest single-day action of the Napoleonic Wars, involving more than 250,000 troops and resulting in at least 70,000 total casualties. The French «Grande Armée» under Emperor Napoleon I attacked the Imperial Russian army of General Mikhail Kutuzov near the village of Borodino, west of the town of Mozhaysk, and eventually captured the main positions on the battlefield, but it failed to destroy the Russian army.

The battle itself ended in disengagement, but strategic considerations and the losses incurred forced the Russians to withdraw next day. The battle at Borodino was a pivotal point in the campaign, since it was the last offensive action fought by Napoleon in Russia. By withdrawing, the Russian army preserved its military potential and eventually forced Napoleon out of the country.

Background

The French «Grande Armée» had begun its invasion of Russia in June, 1812. Czar Alexander I proclaimed a Patriotic War in defence of the motherland. The Russian forces — initially massing along the Polish frontier — fell back before the speedy French advance. Count Michael Barclay de Tolly was serving as commander-in-chief of the Russian army, but his attempts at forming a defensive line were thwarted by the fast moving French. Napoleon had advanced from Vitebsk hoping to catch the Russian Army in the open where he could exterminate it. [Riehn, p. 229.] The French Army was not in a good position since it was 925 km (575 miles) from its nearest logistical base at Kovno. This allowed the Russians to attack the extended French supply lines. [Riehn, p. 230.] Despite this, the lure of a decisive battle drove Napoleon on. The central French force, under Napoleon’s direct command, had crossed the Niemen with 286,000 men, but, by the time of the battle, it numbered 161,475 (most had died of starvation and disease).Riehn, p. 231.] Barclay had been unable to offer battle, which allowed the Grand Armée’s logistic problems to deplete the French. Internal political in-fighting by his sub-commanders also prevented earlier stands by the Russian armies on at least two occasions.Riehn, p. 234.]

Barclay’s constant retreat before the French onslaught was perceived by his fellow generals and by the court as an unwillingness to fight, and he was removed from command. The new Russian commander, Prince Mikhail Kutuzov, was also unable to establish a defensive position until within 125 kilometers of Moscow. Kutuzov picked an eminently defensible area near the village of Borodino and, from September 3, strengthened it with earthworks, notably the Rayevski Redoubt in the center-right of the line and three open, arrow-shaped ‘Bagration flèches’ (named for Petr Bagration) on the Russian left.

Opposing forces

Russian forces present at the battle included 180 infantry battalions, 164 cavalry squadrons, 20 Cossack regiments, and 55 artillery batteries (637 artillery pieces). In total the Russians fielded 103,800 troops. [Riehn. p. 476.] There were 7,000 Cossacks as well as 10,000 Russian militiamen in the area who did not participate in the battle. After the battle the militia units were broken up in order to provide reinforcements to depleted regular infantry battalions. Of the 637 Russian artillery pieces, 300 were held in reserve and many of these guns were never committed to the battle.Smith, p. 392.]

French forces included 214 battalions of infantry, 317 squadrons of cavalry and 587 artillery pieces, a total of 124,000 troops. [Riehn, p. 479.] However, the French Imperial Guard, which consisted of 30 infantry battalions, 27 cavalry squadrons and 109 artillery pieces, 18,500 troops were never committed to action. [Riehn, p. 478.]

Prelude

Kutuzov assumed command on August 29, 1812. [Riehn, p. 237.] The 67-year old general lacked experience in modern warfare and was not seen by his contemporaries as the equal of Napoleon. He was favoured over Barclay, however, because he was Russian, not of German extraction, and it was also believed that he would be able to muster a good defense. [Riehn, p. 235.] Perhaps his greatest strength was that he had the total loyalty of the army and its various sub-commanders.Riehn, p. 236.] Kutuzov ordered another retreat to Gshatsk on August 30 and by that time the ratio of French to Russian forces had shrunk from three to one to five to four. [Riehn, pp. 237–8.] The position at Borodino was selected because it seemed to present the best defensive position before Moscow itself was reached. [Riehn, p. 238.]

The Battle of Shevardino Redoubt

The initial Russian disposition, which stretched south of the new Smolensk Highway (Napoleon’s expected route of advance), was anchored on its left by a pentagonal earthwork redoubt erected on a mound near the village of Shevardino. The French, however, advanced from the west and south of the village, creating a brief but bloody prelude to the main battle. [ [http://www.fortunecity.com/victorian/riley/787/Napoleon/1812/Shevar.html «Battle of Shevardino»] ] The struggle opened on September 4th when Prince Joachim Murat’s French forces met Konovnitzyn’s Russians in a massive cavalry clash. The Russians eventually retreated to the Kolorzkoi Cloister when their flank was threatened. Fighting was renewed on the 5th, but Konovyitzyn again retreated when his flank was threatened by the arrival of Prince Eugene’s Fourth Corps. The Russians retreated to the Shevardino Redoubt, where a sharp fight occurred. Murat led Nansouty’s First Cavalry Corps and Montbrun’s Second Cavalry Corps, supported by Compan’s Division of Louis Nicholas Davout’s First Infantry Corps against the redoubt. Simultaneously, Prince Josef Poniatowski’s infantry attacked the position from the south. The redoubt was taken at the cost of some 4,000 French and 7,000 Russian casualties.Riehn, p. 243.]

The unexpected French advance from the west and the seizure of the Shevardino redoubt threw the Russian position into disarray. The left flank of their defensive position was gone and Russian forces withdrew to the east, having to create a new, makeshift position centered around the village of Utitza. The left flank of the Russian position was, therefore, hanging in the air and ripe for a flanking attack.

Battle of Borodino

The position

The Russian position at Borodino consisted of a series of disconnected earthworks running in an arc from the Moskva River on the right, along its tributary the Kalocha (whose steep banks added to the defense) and towards the village of Utitza on the left.Riehn, p. 244.] Thick woods interspersed along the Russian left and center (on the French side of the Kolocha) also aided the defense by making the deployment and control of French forces difficult. The Russian center was defended by the Raevsky Redoubt, a massive open-backed earthwork mounting 19 12-pounder cannon which had a clear field of fire all the way to the banks of the Kolocha stream.

Kutuzov, who was expecting a corps-sized reinforcement to his right, planned to cross the Kolocha north of Borodino, attack the French left, and roll it up. This helped explain why the more powerful 1st Army under Barclay was placed in already strong positions on the right, which were virtually unassailable by the French. The 2nd Army, under Bagration, was expected to hold on the left but had its left flank hanging in the air. Despite the repeated pleas of his generals to redeploy their forces, Kutuzov did nothing to change these initial dispositions. Thus, when the action began and became a defensive rather than an offensive battle for the Russians, their heavy preponderance in artillery was wasted on a right wing that would never be attacked while the French artillery did much to help win the battle.

Bagration’s «fleches»

Whatever may be said of Kutuzov’s dispositions, Napoleon showed little flair on the battlefield that day. Despite Marshal Davout’s suggestion to a maneuver to out-flank the weak Russian left, the Emperor instead ordered Davout’s First Corps to move directly forward into the teeth of the defense, while the flanking maneuver was left to the weak Fifth Corps of Prince Poniatowski. [Riehn, pp. 243–5.] The initial French attack was aimed at seizing the three Russian positions collectively known as the Bagration flèches, four arrow-head shaped, open-backed earthworks which arced out to the left «en echelon» in front of the Kolocha stream. These positions helped support the Russian left, which had no terrain advantages. The «fleches» were themselves supported by artillery from the village of Semyanovskaya, whose elevation dominated the other side of the Kolocha. The battle began at 0600 with the opening of the 102-gun French grand battery against the Russian center. [Riehn, p. 245] Davout sent Compan’s Division against the southern-most of the «fleches» with Dessaix’s Division echeloned out to the left. When Compans debouched from the woods on the far bank of the Kolocha, he was hit by massed Russian cannon fire. Both Compans and Desaix were wounded, but the attack was pressed forward.Riehn, p. 246.]

Davout, seeing the confusion, personally led his 57th Brigade forward until he had his horse shot from under him. He fell so hard that General Sorbier reported him as dead. General Rapp arrived to replace him only to find Davout alive and leading the 57th forward again. Rapp then lead the 61st Brigade forward when he was wounded (for the 22nd time in his career). By 0730 Davout had gained control of the three «fleches». Prince Bagration quickly led a counterattack that threw the French out of the positions only to have Marshal Michel Ney lead a charge by the 24th Regiment that retook them. Although not enamoured of Barclay, Bagration turned to him for aid, ignoring Kutuzov altogether. Barclay, to his credit, responded with dispatch, sending three guard regiments, eight grenadier battalions, and twenty-four 12 pounder cannon at their best pace to bolster Semyenovskaya. [Riehn, pp. 246–8.] During the confused fighting, French and Russian units moved forward into impenetrable smoke and were smashed by artillery and musketry fire that was horrendous even by Napoleonic standards. Infantry and cavalrymen had difficulty maneuvering over the heaps of corpses and masses of wounded. Prince Murat advanced with his cavalry around the «fleches» to attack Bagration’s infantry, but was confronted by Duka’s 2nd Cuirassier Division supported by Neverovsky’s infantry. This counterpunch drove Murat to seek the cover of allied Wurtemburger Infantry. Barclay’s reinforcements, however, were sent into the fray only to be torn to pieces by French artillery, leaving Friant’s Division in control of the Russian forward position at 1130. Dust, smoke, confusion, and exhaustion all combined to keep the French commanders on the field (Davout, Ney, and Murat) from comprehending that all the Russians before them had fallen back, were in confusion, and ripe for the taking. Reinforcements requested from Napoleon, who had been sick with a cold and too far from the action to really observe what was going on, were refused. It may simply have been a matter of the Emperor refusing to utilize his last reserve, the Imperial Guard, so far from home. [Riehn, p. 247.]

truggle for the Raevsky redoubt

Prince Eugene advanced his corps against the village of Borodino, taking it in a rush from the Russian Guard Jaegers. However, the advancing columns were disordered and once they cleared Borodino, and they faced fresh Russian assault columns that drove the French back to the village. General Delzons was posted to Borodino to prevent the Russians retaking it. [Riehn, p. 248] Morand’s division then crossed to the north side of the Semyenovka Stream, while the remainder of Eugene’s forces crossed three bridges across the Kalocha to the south, placing them on the same side of the stream as the Russians. He then deployed most of his artillery and began to push the Russians back toward the Raevsky redoubt. Broussier and Morand’s divisions then advanced together with furious artillery support. The redoubt changed hands, Paskevitch’s regiment fleeing and having to be rallied by Barclay. [Riehn, p. 249.] Kutuzov then ordered Yermolov to take action and the general brought forward three horse artillery batteries which began to blast the open-ended redoubt while the 3rd Battalion of the Ufa Regiment and two jaeger regiments brought up by Barclay rushed in with the bayonet to eliminate Bonami’s Brigade. [Riehn, pp. 249–50.] This action returned the redoubt to Russian control.

Eugene’s artillery continued to pound Russian support columns while Marshals Ney and Davout set up a crossfire with artillery on the Semenovskoya heights.Riehn, p. 250.] Barclay countered by moving Eugene (Russian) over to the right to support Miloradovitch in his defense of the redoubt.Riehn, p. 251.] When the general brought up troops against an attacking French brigade he described it as «A walk into Hell». During the height of the battle, Kutuzov’s subordinates were making all of the decisions for him. According to Colonel Karl von Clausewitz of On War fame, the Russian commander «seemed to be in a trance.» With the death of General Kutaisov, Chief of Artillery, most of the Russian cannon sat useless on the heights to the rear and were never ordered into battle, while the French artillery was wreaking havoc on the Russians. [Riehn, pp. 250, 251.] At 1400 the assault against the redoubt was renewed by Napoleon with Broussier’s, Morand’s, and Gerard’s divisions launching a massive frontal attack with Chastel’s light cavalry division on their left and the II Reserve Cavalry Corps on their right. General Caulaincourt ordered Wathier’s cuirassier division to lead the assault. Barclay watched Eugene’s (France) assault preparations and countered by moving forces against it. The French artillery, however, began chopping up the assembling force even as it gathered. Caulaincourt led the attack of Wathier’s cuirassiers into the opening at the back of the redoubt and met his death as the charge was stopped cold by Russian musketry. [Riehn, p. 252.] General Thielemann (French) then led eight Saxon and two Polish cavalry squadrons against the back of the redoubt while officers and sergeants of his command actually forced their horses through the redoubt’s embrasures, sowing confusion and allowing the French cavalry and infantry to take the position. The battle had all but ended, with both sides so exhausted that only the artillery was still at work. [Riehn, p. 253.] Napoleon once again refused to release the guard and the battle wound down around 1600. [Riehn, pp. 254–5.]

End of the battle

Barclay communicated with Kutuzov in order to receive further instructions. According to Wolzogen (in an account dripping with sarcasm), the commander was found a half-hour away on the road to Moscow, encamped with an entourage of young nobles and grandly pronouncing he would drive Napoleon off the next day. [Riehn, pp. 253–4.] Despite his bluster, Kutuzov knew from dispatches that his army had been too damaged to fight a continuing action the following day. He knew exactly what he was doing: by fighting the pitched battle he could now retreat with the Russian army still intact, lead its recovery, and force the damaged French forces to move even further from their bases of supply. The «denouement» became a textbook example of what a hold logistics placed upon an army far from its center of logistics. [Riehn, p. 260.] On September 8th, the Russian army moved away from the battlefield in twin columns to Semolino, allowing Napoleon to occupy Moscow and await a Russian surrender that would never come.

Casualties

The casualties of the battle were staggering: at least 28,000 French soldiers and 29 generals were reported as dead, wounded, or missing. 52,000 Russian troops also were reported as dead, wounded or missing, although 8,000 Russians would later return to their formations bringing Russian losses to around 44,000. 22 Russian generals were dead or wounded, including Prince Bagration.Riehn, p. 255.] It should be noted that a wound upon that battlefield was a death sentence as often as not, there not being enough food for the healthy. As many wounded died of starvation as from their wounds or lack of care. [Riehn, p. 261.]

French infantrymen had expended almost two million rounds of ammunition, while their artillery had expended some 60,000 rounds. This amount of flying metal had severe effects on the participants. Around 8,500 casualties were sustained during each hour of the conflict — the equivalent of a full-strength company wiped out every minute. In some divisions casualties exceeded 80 percent of reported strength prior to the battle. [Alexander Mikaberidze, «The Battle of Borodino: Napoleon Against Kutuzov», London: Pen & Sword, 2007, ISBN-10 1844156036 ISBN-13 978-1844156030] .

Legacy

Napoleon’s own account of the battle gives a good understanding of it: «Of the fifty battles I have fought, the most terrible was that before Moscow. The French showed themselves to be worthy victors, and the Russians can rightly call themselves invincible.» [http://www.napoleon.org/en/magazine/museums/files/Borodino.asp Borodino] , Napoleon.org.]

Poet Mikhail Lermontov romanticised the battle in his poem [http://www.stihi-rus.ru/1/Lermontov/11-1.htm Borodino] , based on the account of his uncle, a combat participant. The battle was famously described by Count Leo Tolstoy in his novel «War and Peace» as «a continuous slaughter which could be of no avail either to the French or the Russians». A huge panorama representing the battle was painted by Franz Roubaud for the centenary of Borodino and installed on the Poklonnaya Hill in Moscow to mark the 150th anniversary of the event. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky also composed his «1812 Overture» to commemorate the battle.

There exists today a tradition of reenacting the battle on August 26. On the battlefield itself, the Bagration «fleches» are still preserved and there is a modest monument to the French soldiers who fell in the battle. There are also remnants of trenches from the seven-day battle fought at the same battlefield in 1941 between the Soviet and German forces (which took fewer human lives than the one of 1812).

A commemorative 1-ruble coin was released in the USSR in 1987 to commemorate the 175th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino, and four million of them were minted. [ [http://mint.hobby.ru/pm032.htm Добро пожаловать на сервер «Монетный двор» ] ] A minor planet 3544 Borodino, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1977 was named after the village Borodino. [cite book|last= Schmadel|first=Lutz D.|title=Dictionary of Minor Planet Names|pages=p. 298|edition=5th|year=2003|publisher=Springer Verlag |location=New York|url=http://books.google.com/books?q=3543+Ningbo+1964|id=ISBN 3540002383]

Footnotes

References

* Chandler, David G. «Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars» London: Wordsworth editions Ltd., 1999.

* Chandler, David G. «The Campaigns of Napoleon.» New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-02-523660-1

* Duffy, Christopher, «Borodino and the War of 1812». London: Cassell & Company, 1972.

* Hourtoulle, F.G. «Borodino/The Moskova: The Battle for the Redoubts». Paris: Histoire & Collections, 2000.

* Mikaberidze, Alexander. «The Battle of Borodino: Napoleon Against Kutuzov». London: Pen & Sword, 2007.

* Markham, David. «Napoleon for Dummies» New York: Wiley Pub Inc., 2005).

* Nafziger, George F. «Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia». Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1988.

* Riehn, Richard K. «Napoleon’s Russian Campaign», John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

* Smith, D(?), «The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book». London: Greenhill Books, 1998.

* Troitskiy, N.A. Фельдмаршал Кутузов: Мифы и Факты, Центрполиграф («Field Marshal Kutuzov: Myths and Facts»), (publisher unknown) 2002.

* «История военного искусства» («History of Military Art»), М. Воениздат, 1966. — Russian source (publisher and translation of author’s name?)

Monuments

External links

* [http://www.wtj.com/archives/lejeune1.htm First-hand account of the battle] by Louis-François, Baron Lejeune a French aide-de-camp

* [http://www.fortunecity.com/victorian/riley/787/Napoleon/1812/boro1.html A very detailed description of the battle]

* [http://napoleonistyka.atspace.com/Borodino_battle.htm Borodino: maps, diagrams, illustrations]

* [http://www.hamilton.edu/academics/Russian/warandpeace/vb/ The Virtual Battle of Borodino]

* [http://www.allworldwars.com/The%20Batlle%20of%20Borodino%20September%207%201812.html The Battle of Borodino, situation at 12.30 p.m. Visual tour of Borodino Panorama by Franz A. Roubaud]

* [http://izpitera.ru/foto/2007-09-02_borodino/ «The battle of Borodino reconstruction. 195 Anniversary Photos»]

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

-

1

the battle of Borodino

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > the battle of Borodino

-

2

(the) battle of Stalingrad

Сталинградская (Бородинская, Курская) битва

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > (the) battle of Stalingrad

-

3

при

предл.;

(ком-л./чем-л.)

1) by, at, near;

of при впадении Оки в Волгу ≈ where the Oka flows into the Volga битва при Бородине ≈ the battle of Borodino быть при смерти ≈ to be near death

2) attached to ясли при заводе ≈ nursery attached to a factory

3) in the presence of при мне ≈ in my presence при свидетелях ≈ in the presence of witnesses

4) during при жизни( кого-л.) ≈ during the life (of)

5) (при правителе или режиме) under, in the time of при Сталине

6) at, on, upon, when при переходе через улицу ≈ when crossing the street при упоминании

7) on the person (of) документы при себе ≈ documents on one’s person

having, possessing быть при деньгах ≈ to have plenty of money

9) under, in view (of), given при таких условиях ≈ under such conditions при всем том ≈ for all that быть ни при чем ≈ have nothing to do with (it), not to be smb.’s fault при сем ≈ herewith;

enclosedБольшой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > при

См. также в других словарях:

-

Battle of Borodino — Infobox Military Conflict conflict=Battle of Borodino partof=French invasion of Russia (1812) caption=An unnamed painting of the Battle of Borodino by an unspecified artist date=September 7, 1812 place=Borodino, Russia result= French victory… … Wikipedia

-

Battle at Borodino Field — Infobox Military Conflict conflict=Battle at Borodino Field caption= partof=the Battle of Moscow place=Borodino, Russian SSR date=13 October 1941 18 January, 1942 result=German victory combatant1=flag|Nazi Germany|name=Germany… … Wikipedia

-

Borodino (disambiguation) — Borodino is a village of Russia famous for the Battle of Borodino.Borodino may also refer to one of the following.*Borodino class battleship, a class of Russian pre dreadnought battleships *Borodino class battlecruiser, a class of Russian… … Wikipedia

-

Borodino (poem) — Borodino ( ru. Бородино) is a poem by Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov which describes the Battle of Borodino, the turning point of the Napoleon s invasion of Russia. It was first published in 1837 in literary magazine Sovremennik on the occasion… … Wikipedia

-

Borodino — ( ru. Бородино) is a village in Moscow Oblast, Russia, 12 km southwards of Mozhaysk.The village is famous as the location of the Battle of Borodino, which occurred in what is now known as the Borodino Battlefield (Бородинское поле). The State… … Wikipedia

-

Borodino class battleship — The five Borodino class battleships (also known as the Suvorov class) were pre dreadnoughts built between 1899 and 1905 for the Imperial Russian Navy. Three of the class were sunk and one captured by the Imperial Japanese Navy in a decisive naval … Wikipedia

-

battle — battle1 battler, n. /bat l/, n., v., battled, battling. n. 1. a hostile encounter or engagement between opposing military forces: the battle of Waterloo. 2. participation in such hostile encounters or engagements: wounds received in battle. 3. a… … Universalium

-

Battle of Moscow — For the 1812 battle during the Napoleonic Wars, see Battle of Borodino. Battle of Moscow Part of the Eastern Front of World War II … Wikipedia

-

Battle of Tarutino — Infobox Military Conflict conflict=Battle of Tarutino partof=French invasion of Russia (1812) caption= Battle of Tarutino , by Piter von Hess date=October 18, 1812 place=Tarutino, Russia result=Russian victory combatant1= combatant2=… … Wikipedia

-

Battle of Tsushima — Part of the Russo Japanese War … Wikipedia

-

Battle of Maloyaroslavets — Part of the French invasion of Russia (1812) Battle of Maloyaroslavets, by Piter von Hess … Wikipedia

- The exact number of soldiers fallen on Borodino Field remains unknown. In 1812, at least 40,000 Russian soldiers are estimated to have been killed in battle here.

- On Borodino Field there are some 40 monuments, a museum devoted to the Patriotic War of 1812, the Spaso-Borodinsky Convent and the Church of the Smolensk Icon of the Mother of God (17th-18th)

- Fortifications dating back to the Battle of Borodino have been restored here.

- The Spaso-Borodinsky Convent features, in addition to the religious buildings, the house of hegumenia Maria (Tuchkova) and the gallery of the Battle of Borodino.

- The Borodino War Museum displays weapons, costumes and household items unearthed during excavations as well as a small-scale replica of the battlefield.

- Information in the museums is available in Russian only.

Borodino fieldRussian: Borodinskoe pole or Бородинское поле is a huge memorial monument built in honour of the Russian military. Situated not far from the settlement of BorodinoRussian: Бородино, it is built on the site of two major battles which occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries. Napoleon’s Grand army and the Russian troops led by M. Kutuzova Field Marshal of the Russian Empire, who served as one of the finest military officers and diplomats of Russia under the reign of Catherine II, Paul I and Alexander I fought here on 26 August, 1812. In 1941 and 1942, a second battle, the Moscow Battle, raged here with the Soviet Army fighting Nazi troops.

SPASO-BORODINSKY CONVENT AND ITS MEMORIAL EXHIBITIONS

Tuchkov’s widow never did find her husband’s body. She began, however, the construction of a church dedicated to the icon of Saviour Not Made by HandsRussian: ikona Spasa Nerukotvornogo or икона Спаса Нерукотворного on the alleged site of her husband’s death. She had to sell her family jewelry to buy a plot of land and build the church on it. When Emperor Alexander Ireigned as Emperor of Russia from 1801 to 1825 learned about this, he donated a considerable amount of money for the cause. This is how a convent appeared on the field, together with the church. Later, Margarita Tuchkova took monastic vows, becoming the convent’s hegumenia, or Mother Superior, after the deaths of her son and brother. Her body rests here, too.

Borodino field features another structure that appeared here even before those dire events, the Church of the Smolensk Icon of the Mother of God constructed in the late 17 and early 18th centuries. Typical of its time (an octagon placed on a quadrangle, with a bell tower), it has become both an architectural and historic monument, and it is from this bell tower that the Russian commanders observed the battle.

This sight is located far away from the city center, and it is comfortable to use a taxi to reach it. If you are interested in cabs in Moscow, you can read about it on our website page “Taxi in Moscow”.

BORODINO WAR MUSEUM

© 2016-2022 moscovery.com

How interesting and useful was this article for you?

Ответы

Ответ добавил: Гость

1. he lives in pushkin street.

2. they stayed in st. petersburg for five days.

3. we saw a lot of well-known pictures in this museum.

4. my father works from morning till late evening.

5. ann has never been to the tower of london before.

6. could you tell me how to get to westminister abbey?

Ответ добавил: Гость

who is going to take an umbrell?

are you going to take an umbrella or a rain coat?

i`m not going to take an umbrella, am i?

what am i going to take?

am i going to take an umbrella?

Ответ добавил: Гость

it is grey — он серый

his rabbit is big and fat — его кролик большой и толстый

it can sit and skip — он может сидеть и прыгать

Ответ добавил: Гость

мин сиңа ярдәм итә алам, син монда язган, дип әйт ?

Больше вопросов по английскому языку

| Battle of Borodino | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French invasion of Russia | ||||||||

Battle of Moscow, 7th September 1812, 1822 by Louis-François Lejeune |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| |

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| 103,000–135,000 | 125,000–160,000 | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| 28,000–40,000 killed, wounded or captured | 40,000–45,000 killed, wounded or captured |

current battle

Prussian corps

Napoleon

Austrian corps

The Battle of Borodino (Russian pronunciation: [bərədʲɪˈno])[a] took place near the village of Borodino on 7 September [O.S. 26 August] 1812 during Napoleon’s French invasion of Russia. The Grande Armée won the battle against the Imperial Russian Army with casualties in a ratio 2:3, but failed to gain a decisive victory. Napoleon fought against General Mikhail Kutuzov, whom the Emperor Alexander I of Russia had appointed to replace Barclay de Tolly on 29 August [O.S. 17 August] 1812 after the Battle of Smolensk. After the Battle of Borodino, Napoleon remained on the battlefield with his army; the Russian forces retreated in an orderly fashion to the south of Moscow.

Background[edit]

Napoleon’s invasion of Russia[edit]

Napoleon with the French Grande Armée began his invasion of Russia on 24 June 1812 by crossing the Niemen.

As his Russian army was outnumbered by far, Mikhail Bogdanovich Barclay de Tolly successfully used a «delaying operation», defined as an operation in which a force under pressure trades space for time by slowing down the enemy’s momentum and inflicting maximum damage on the enemy without, in principle, becoming decisively engaged,[better source needed] by retreating further eastwards into Russia without giving battle. But the Tsar replaced the unpopular Barclay de Tolly with Kutuzov, who on 18 August took over the army at Tsaryovo-Zaymishche and ordered his men to prepare for battle. Kutuzov understood that Barclay’s decision to retreat had been correct, but the Tsar, the Russian troops and Russia could not accept further retreat. A battle had to occur in order to preserve the morale of the soldiers and the nation. He then ordered not another retreat eastwards but a search for a battleground eastwards to Gzhatsk (Gagarin) on 30 August, by which time the ratio of French to Russian forces had shrunk from 3:1 to 5:4 thus using Barclay’s delaying operation again. The main part of Napoleon’s army had entered Russia with 286,000 men but by the time of the battle was reduced mostly through starvation and disease

Kutuzov’s army established a defensive line near the village of Borodino. Although the Borodino field was too open and had too few natural obstacles to protect the Russian center and the left flank, it was chosen because it blocked both Smolensk–Moscow roads and because there were simply no better locations. Starting on 3 September, Kutuzov strengthened the line with earthworks, including the Raevski Redoubt in the center-right of the line and three open, arrow-shaped «Bagration flèches» (named after Pyotr Bagration) on the left.

Battle of Shevardino Redoubt[edit]

The initial Russian position, which stretched south of the new Smolensk Highway (Napoleon’s expected route of advance), was anchored on its left by a pentagonal earthwork redoubt erected on a mound near the village of Shevardino. The Russian generals soon realized that their left wing was too exposed and vulnerable,[18] so the Russian line was moved back from this position, but the Redoubt remained manned, Kutuzov stating that the fortification was manned simply to delay the advance of the French forces. Historian Dmitry Buturlin reports that it was used as an observation point to determine the course of the French advance. Historians Witner and Ratch, and many others, reported it was used as a fortification to threaten the French right flank, despite being beyond the effective reach of guns of the period.

The Chief of Staff of the Russian 1st Army, Aleksey Yermolov, related in his memoirs that the Russian left was shifting position when the French Army arrived sooner than expected; thus, the Battle of Shevardino became a delaying effort to shield the redeployment of the Russian left. The construction of the redoubt and its purpose is disputed by historians to this day.

The conflict began on September 5 when Marshal Joachim Murat’s French forces met Konovnitzyn’s Russians in a massive cavalry clash, the Russians eventually retreating to the Kolorzkoi Cloister when their flank was threatened. Fighting resumed the next day but Konovnitzyn again retreated when Viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais’ Fourth Corps arrived, threatening his flank. The Russians withdrew to the Shevardino Redoubt, where a pitched battle ensued. Murat led Nansouty’s First Cavalry Corps and Montbrun’s Second Cavalry Corps, supported by Compans’s Division of Louis Nicolas Davout’s First Infantry Corps against the redoubt. Simultaneously, Prince Józef Poniatowski’s Polish infantry attacked the position from the south. Fighting was heavy and very fierce, as the Russians refused to retreat until Kutuzov personally ordered them to do so.[18] The French captured the redoubt, at a cost of 4,000–5,000 French and 6,000 Russian casualties. The small redoubt was destroyed and covered by the dead and dying of both sides.

The unexpected French advance from the west and the fall of the Shevardino redoubt threw the Russian formation into disarray. Since the left flank of their defensive position had collapsed, Russian forces withdrew to the east, constructing a makeshift position centered around the village of Utitsa. The left flank of the Russian position was thus ripe for a flanking attack.

Opposing forces[edit]

Battle of Borodino, by Peter von Hess, 1843. In the center it shows Bagration after being wounded.

A series of reforms to the Russian army had begun in 1802, creating regiments of three battalions, each battalion having four companies. The defeats of Austerlitz, Eylau, and Friedland led to important additional reforms, though continuous fighting in the course of three wars with France, two with Sweden, and two with the Ottoman Empire had not allowed time for these to be fully implemented and absorbed. A divisional system was introduced in 1806, and corps were established in 1812. Prussian influence may be seen in the organizational setup. By the time of Borodino the Russian army had changed greatly from the force which met the French in 1805–07.[citation needed]

Russian forces present at the battle included 180 infantry battalions, 164 cavalry squadrons, 20 Cossack regiments, and 55 artillery batteries (637 artillery pieces). In total, the Russians fielded 155,200 troops. There were 10,000 Cossacks as well as 33,000 Russian militiamen in the area who did not participate in the battle. After the battle the militia units were broken up to provide reinforcements to depleted regular infantry battalions. Of the 637 Russian artillery pieces, 300 were held in reserve and many of these were never committed to the battle.

According to historian Alexander Mikaberidze, the French army remained the finest army of its day by a good margin. The fusion of the legacy of the Ancien Régime with the formations of the French revolution and Napoleon’s reforms had transformed it into a military machine that had dominated Europe since 1805. Each corps of the French army was in fact its own mini-army capable of independent action.

French forces included 214 battalions of infantry, 317 squadrons of cavalry and 587 artillery pieces totaling 128,000 troops. However, the French Imperial Guard, which consisted of 30 infantry battalions, 27 cavalry squadrons and 109 artillery pieces—a total of 18,500 troops—never committed to action.

Battle[edit]

Position[edit]

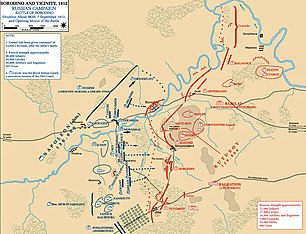

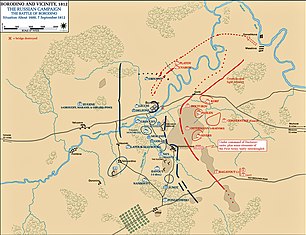

Situation about 0630

Situation about 0930

Situation about 1600

(by West Point Military Academy)

According to Carl von Clausewitz, although the Russian left was on marginally higher ground, this was but a superficial matter and did not provide much of a defensive advantage. The positioning of the Russian right was such that for the French the left seemed an obvious choice. The Russian position at Borodino consisted of a series of disconnected earthworks running in an arc from the Moskva River on the right, along its tributary, the Kolocha (whose steep banks added to the defense), and towards the village of Utitsa on the left. Thick woods interspersed along the Russian left and center (on the French side of the Kolocha) made the deployment and control of French forces difficult, aiding the defenders. The Russian center was defended by the Raevsky Redoubt, a massive open-backed earthwork mounting nineteen 12-pounder cannons which had a clear field of fire all the way to the banks of the Kolocha stream.[citation needed]

Kutuzov was very concerned that the French might take the New Smolensk Road around his positions and on to Moscow so placed the more powerful 1st Army under Barclay on the right, in positions which were already strong and virtually unassailable by the French. The 2nd Army under Bagration was expected to hold the left. The fall of Shevardino unanchored the Russian left flank but Kutuzov did nothing to change these initial dispositions despite the repeated pleas of his generals to redeploy their forces.

Thus, when the action began and became a defensive rather than an offensive battle for the Russians, their heavy preponderance in artillery was wasted on a right wing that would never be attacked, while the French artillery did much to help win the battle Colonel Karl Wilhelm von Toll and others would make attempts to cover up their mistakes in this deployment and later attempts by historians would compound the issue. Indeed, Clausewitz also complained about Toll’s dispositions being so narrow and deep that needless losses were incurred from artillery fire. The Russian position therefore was just about 8 kilometres (5 mi) long with about 80,000 of the 1st Army on the right and 34,000 of the 2nd Army on the left.

Bagration’s flèches[edit]

The first area of operations was on the Bagration flèches, as had been predicted by both Barclay de Tolly and Bagration.

Napoleon, in command of the French forces, made errors similar to those of his Russian adversary, deploying his forces inefficiently and failing to exploit the weaknesses in the Russian line. Despite Marshal Davout’s suggestion of a maneuver to outflank the weak Russian left, the Emperor instead ordered Davout’s First Corps to move directly forward into the teeth of the defense, while the flanking maneuver was left to the weak Fifth Corps of Prince Poniatowski.

The initial French attack was aimed at seizing the three Russian positions collectively known as the Bagration flèches, three arrow-head shaped, open-backed earthworks which arced out to the left en échelon in front of the Kolocha stream. These positions helped support the Russian left, which had no terrain advantages. There was much to be desired in the construction of the flèches, one officer noting that the ditches were much too shallow, the embrasures open to the ground, making them easy to enter, and that they were much too wide, exposing infantry inside them. The flèches were supported by artillery from the village of Semyanovskaya, whose elevation dominated the other side of the Kolocha.

The battle began at 06:00 with the opening of the 102-gun French grand battery against the Russian center. Davout sent Compans’s Division against the southernmost of the flèches, with Dessaix’s Division echeloned out to the left. When Compans exited the woods on the far bank of the Kolocha, he was hit by massed Russian cannon fire; both Compans and Dessaix were wounded, but the French continued their assault.

Davout, seeing the confusion, personally led the 57th Line Regiment (Le Terrible) forward until he had his horse shot from under him; he fell so hard that General Sorbier reported him as dead. General Rapp arrived to replace him, only to find Davout alive and leading the 57th forward again. Rapp then led the 61st Line Regiment forward when he was wounded (for the 22nd time in his career).[citation needed]

By 07:30, Davout had gained control of the three flèches. Prince Bagration quickly led a counterattack that threw the French out of the positions, only to have Marshal Michel Ney lead a charge by the 24th Regiment that retook them. Although not enamoured of Barclay, Bagration turned to him for aid, ignoring Kutuzov altogether; Barclay, to his credit, responded quickly, sending three guard regiments, eight grenadier battalions, and twenty-four 12-pounder cannon at their best pace to bolster Semyаnovskaya. Colonel Toll and Kutuzov moved the Guard Reserve units forward as early as 09:00 hours.

Ney’s infantry push Russian grenadiers back from the flèches (which can be seen from the rear in the background). Detail from the Borodino Panorama.

During the confused fighting, French and Russian units moved forward into impenetrable smoke and were smashed by artillery and musketry fire that was horrendous even by Napoleonic standards. Infantry and cavalrymen had difficulty maneuvering over the heaps of corpses and masses of wounded. Murat advanced with his cavalry around the flèches to attack Bagration’s infantry, but was confronted by General Duka’s 2nd Cuirassier Division supported by Neverovsky’s infantry.

The French carried out seven assaults against the flèches and each time were beaten back in fierce close combat. Bagration in some instances was personally leading counterattacks, and in a final attempt to push the French completely back he got hit in the leg by cannonball splinters somewhere around 11:00 hours. He insisted on staying on the field to observe Duka’s decisive cavalry attack.

This counter-punch drove Murat to seek the cover of allied Württemberger infantry. Barclay’s reinforcements, however, were sent into the fray only to be torn to pieces by French artillery, leaving Friant’s Division in control of the Russian forward position at 11:30. Dust, smoke, confusion, and exhaustion all combined to keep the French commanders on the field (Davout, Ney, and Murat) from comprehending that all the Russians before them had fallen back, were in confusion, and ripe for the taking.

The 2nd Army’s command structure fell apart as Bagration was removed from the battlefield and the report of his being hit quickly spread and caused morale collapse. Napoleon, who had been sick with a cold and was too far from the action to really observe what was going on, refused to send his subordinates reinforcements. He was hesitant to release his last reserve, the Imperial Guard, so far from France.

First attacks on the Raevsky redoubt[edit]

Saxon cuirassiers and Polish lancers of Latour-Maubourg’s cavalry corps clash with Russian cuirassiers. The rise of Raevsky redoubt is on the right, the steeple of Borodino church in the background. Detail from the Borodino Panorama.

Prince Eugène de Beauharnais advanced his corps against Borodino, rushing the village and capturing it from the Russian Guard Jägers. However, the advancing columns rapidly lost their cohesion; shortly after clearing Borodino, they faced fresh Russian assault columns and retreated back to the village. General Delzons was posted to Borodino to prevent the Russians retaking it.

Morand’s division then crossed to the north side of the Semyenovka stream, while the remainder of Eugène’s forces traversed three bridges across the Kolocha to the south, placing them on the same side of the stream as the Russians. He then deployed most of his artillery and began to push the Russians back toward the Raevsky redoubt. Broussier and Morand’s divisions then advanced together with furious artillery support. The redoubt changed hands as Barclay was forced to personally rally Paskevitch’s routed regiment.

Kutuzov ordered Yermolov to take action; the general brought forward three horse artillery batteries that began to blast the open-ended redoubt, while the 3rd Battalion of the Ufa Regiment and two Jäger regiments brought up by Barclay rushed in with the bayonet to eliminate Bonami’s Brigade. The Russian reinforcements’ assault returned the redoubt to Russian control.

French and Russian cavalry clash behind the Raevsky redoubt. Details from Roubaud’s panoramic painting.

Eugène’s artillery continued to pound Russian support columns, while Marshals Ney and Davout set up a crossfire with artillery positioned on the Semyonovskaya heights. Barclay countered by moving the Prussian General Eugen over to the right to support Miloradovich in his defense of the redoubt. The French responded to this move by sending forward General Sorbier, commander of the Imperial Guard artillery. Sorbier brought forth 36 artillery pieces from the Imperial Guard Artillery Park and also took command of 49 horse artillery pieces from Nansouty’s Ist Cavalry Corps and La Tour Maubourg’s IV Cavalry Corps, as well as of Viceroy Eugène’s own artillery, opening up a massive artillery barrage.

When Barclay brought up troops against an attacking French brigade, he described it as «a walk into Hell». During the height of the battle, Kutuzov’s subordinates were making all of the decisions for him; according to Colonel Karl von Clausewitz, famous for his work On War, the Russian commander «seemed to be in a trance.» With the death of General Kutaisov, Chief of Artillery, most of the Russian cannon sat useless on the heights to the rear and were never ordered into battle, while the French artillery wreaked havoc on the Russians.

Cossack raid on the northern flank[edit]

On the morning of the battle at around 07:30, Don Cossack patrols from Matvei Platov’s pulk had discovered a ford across the Kolocha river, on the extreme Russian right (northern) flank. Seeing that the ground in front of them was clear of enemy forces, Platov saw an opportunity to go around the French left flank and into the enemy’s rear. He at once sent one of his aides to ask for permission from Kutuzov for such an operation. Platov’s aide was lucky enough to encounter Colonel von Toll, an enterprising member of Kutuzov’s staff, who suggested that General Uvarov’s Ist Cavalry Corps be added to the operation and at once volunteered to present the plan to the commander-in-chief.[18]

Together, they went to see Kutuzov, who nonchalantly gave his permission. There was no clear plan and no objectives had been drawn up, the whole manoeuvre being interpreted by both Kutuzov and Uvarov as a feint. Uvarov and Platov thus set off, having just around 8000 cavalrymen and 12 guns in total, and no infantry support. As Uvarov moved southwest and south and Platov moved west, they eventually arrived in the undefended rear of Viceroy Eugène’s IV Corps. This was towards midday, just as the Viceroy was getting his orders to conduct another assault on the Raevski redoubt.[18]

The sudden appearance of masses of enemy cavalry so close to the supply train and the Emperor’s headquarters caused panic and consternation, prompting Eugène to immediately cancel his attack and pull back his entire Corps westwards to deal with the alarming situation. Meanwhile, the two Russian cavalry commanders tried to break what French infantry they could find in the vicinity. Having no infantry of their own, the poorly coordinated Russian attacks came to nothing.[18]

Unable to achieve much else, Platov and Uvarov moved back to their own lines and the action was perceived as a failure by both Kutuzov and the Russian General Staff. As it turned out, the action had the utmost importance in the outcome of the battle, as it delayed the attack of the IV Corps on the Raevski redoubt for a critical two hours. During these two hours, the Russians were able to reassess the situation, realize the terrible state of Bagration’s 2nd Army and send reinforcements to the front line. Meanwhile, the retreat of Viceroy Eugène’s Corps had left Montbrun’s II French Cavalry Corps to fill the gap under the most murderous fire, which used up and demoralized these cavalrymen, greatly reducing their combat effectiveness. The delay contradicted a military principle the Emperor had stated many times: «Ground I may recover, time never.» The Cossack raid contributed to Napoleon’s later decision not to commit his Imperial Guard to battle.[18]

Final attack on Raevsky redoubt[edit]

At 14:00, Napoleon renewed the assault against the redoubt, as Broussier’s, Morand’s, and Gérard’s divisions launched a massive frontal attack, with Chastel’s light cavalry division on their left and the II Reserve Cavalry Corps on their right;

The Russians sent Likhachov’s 24th Division into the battle, who fought bravely under Likhachov’s motto: «Brothers, behind us is Moscow!» But the French troops approached too close for the cannons to fire, and the cannoneers fought a pitched close-order defence against the attackers.[18] General Caulaincourt ordered Watier’s cuirassier division to lead the assault. Barclay saw Eugène’s preparations for the assault and attempted to counter it, moving his forces against it. The French artillery, however, began bombarding the assembling force even as it gathered. Caulaincourt led Watier’s cuirassiers in an assault on the opening at the back of the redoubt; he was killed as the charge was beaten off by fierce Russian musketry.

General Thielmann then led eight Saxon and two Polish cavalry squadrons against the back of the redoubt, while officers and sergeants of his command actually forced their horses through the redoubt’s embrasures, sowing confusion amongst the defenders and allowing the French cavalry and infantry to take the position. The battle had all but ended, with both sides so exhausted that only the artillery was still at work. At 15:30, the Raevsky redoubt fell with most of the 24th Division’s troops. General Likhachov was captured by the French.

Utitsa[edit]

The third area of operations was around the village of Utitsa. The village was at the southern end of the Russian positions and lay along the old Smolensk road. It was rightly perceived as a potential weak point in the defense as a march along the road could turn the entire position at Borodino. Despite such concerns the area was a tangle of rough country thickly covered in heavy brush well suited for deploying light infantry. The forest was dense, the ground marshy, and Russian Jaegers were deployed there in some numbers. Russian General Nikolay Tuchkov had some 23,000 troops but half were untrained Opolchenye (militia) armed only with pikes and axes and not ready for deployment.

Poniatowski had about 10,000 men, all trained and eager to fight, but his first attempt did not go well. It was at once realized the massed troops and artillery could not move through the forest against Jaeger opposition so had to reverse to Yelnya and then move eastward. Tuchkov had deployed his 1st Grenadier Division in line backing it with the 3rd division in battalion columns. Some four regiments were called away to help defend the redoubts that were under attack and another 2 Jaeger regiments were deployed in the Utitsa woods, weakening the position.

The Polish contingent contested control of Utitsa village, capturing it with their first attempt. Tuchkov later ejected the French forces by 08:00. General Jean-Andoche Junot led the Westphalians to join the attack and again captured Utitsa, which was set on fire by the departing Russians. After the village’s capture, Russians and Poles continued to skirmish and cannonade for the rest of the day without much progress. The heavy undergrowth greatly hindered Poniatowski’s efforts but eventually he came near to cutting off Tuchkov from the rest of the Russian forces.

General Barclay sent help in the form of Karl Gustav von Baggovut with Konovnitzyn in support. Any hope of real progress by the Poles was then lost.

Napoleon’s refusal to commit the Guard[edit]

Towards 15:00, after hours of resistance, the Russian army was in dire straits, but the French forces were exhausted and had neither the necessary stamina nor will to carry out another assault. Both armies were exhausted after the battle and the Russians withdrew from the field the following day. Borodino represented the last Russian effort at stopping the French advance on Moscow, which fell a week later. At this crucial juncture, Murat’s chief of staff, General Augustin Daniel Belliard rode straight to the Emperor’s Headquarters and, according to General Ségur who wrote an account of the campaign, told him that the Russian line had been breached, that the road to Mozhaysk, behind the Russian line, was visible through the gaping hole the French attack had pierced, that an enormous crowd of runaways and vehicles were hastily retreating, and that a final push would be enough to decide the fate of the Russian army and of the war. Generals Daru, Dumas and Marshal Louis Alexandre Berthier also joined in and told the Emperor that everyone thought the time had come for the Guard to be committed to battle.[citation needed]

Given the ferocity of the Russian defense, everyone was aware that such a move would cost the lives of thousands of Guardsmen, but it was thought that the presence of this prestigious unit would bolster the morale of the entire army for a final decisive push. A notable exception was Marshal Bessières, commander of the Guard cavalry, who was one of the very few senior generals to strongly advise against the intervention of the Guard. As the general staff were discussing the matter, General Rapp, a senior aide-de-camp to the Emperor, was being brought from the field of battle, having been wounded in action.

Rapp immediately recommended to the Emperor that the Guard be deployed for action at which the Emperor is said to have retorted: «I will most definitely not; I do not want to have it blown up. I am certain of winning the battle without its intervention.» Determined not to commit this valuable final reserve so far away from France, Napoleon rejected another such request, this time from Marshal Ney. Instead, he called the commander of the «Young Guard», Marshal Mortier and instructed him to guard the field of battle without moving forward or backward, while at the same time unleashing a massive cannonade with his 400 guns.

End of the battle[edit]

Napoleon went forward to see the situation from the former Russian front lines shortly after the redoubts had been taken. The Russians had moved to the next ridge-line in much disarray; however, that disarray was not clear to the French, with dust and haze obscuring the Russian dispositions. Kutuzov ordered the Russian Guard to hold the line and so it did. All of the artillery that the French army had was not enough to move it. Those compact squares made good artillery targets and the Russian Guard stood in place from 4 pm to 6 pm unmoving under its fire, resulting in huge casualties. All he could see were masses of troops in the distance and thus nothing more was attempted. Neither the attack, which relied on brute force, nor the refusal to use the Guard to finish the day’s work, showed any brilliance on Napoleon’s part.

M. I. Kutuzov and his staff in the meeting at Fili village, when Kutuzov decided that the Russian army had to retreat from Moscow.

Painting by Aleksey Kivshenko.

Both the Prussian Staff Officer Karl von Clausewitz, the historian and future author of On War, and Alexander I of Russia noted that the poor positioning of troops in particular had hobbled the defense. Barclay communicated with Kutuzov in order to receive further instructions. According to Ludwig von Wolzogen (in an account dripping with sarcasm), the commander was found a half-hour away on the road to Moscow, encamped with an entourage of young nobles and grandly pronouncing he would drive Napoleon off the next day.

Despite his bluster, Kutuzov knew from dispatches that his army had been too badly hurt to fight a continuing action the following day. He knew exactly what he was doing: by fighting the pitched battle, he could now retreat with the Russian army still intact, lead its recovery, and force the weakened French forces to move even further from their bases of supply. The dénouement became a textbook example of what a hold logistics placed upon an army far from its center of supply. On September 8, the Russian army moved away from the battlefield in twin columns, allowing Napoleon to occupy Moscow and await for five weeks a Russian surrender that would never come.

Kutuzov would proclaim over the course of several days that the Russian Army would fight again before the walls of Moscow. In fact, a site was chosen near Poklonnaya Gora within a few miles of Moscow as a battle site. However, the Russian Army had not received enough reinforcements, and it was too risky to cling to Moscow at all costs. Kutuzov understood that the Russian people never wanted to abandon Moscow, the city which was regarded as Russia’s «second capital»; however he also believed that the Russian Army did not have enough forces to protect that city. Kutuzov called for a council of war in the afternoon of 13 September at Fili village. In a heated debate that split the council five to four in favour of giving battle, Kutuzov, after listening to each General, endorsed retreat. Thus passed the last chance of battle before Moscow was taken.[18]

Historiography[edit]

| Estimates of the sizes of opposing forces | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| made at different times by different historians | |||

| Historian | French | Russian | Year |

| Buturlin | 190,000 | 132,000 | 1824 |

| Segur | 130,000 | 120,000 | 1824 |

| Chambray | 133,819 | 130,000 | 1825 |

| Fain | 120,000 | 133,500 | 1827 |

| Clausewitz | 130,000 | 120,000 | 1830s |

| Mikhailovsky-Danilivsky | 160,000 | 128,000 | 1839 |

| Bogdanovich | 130,000 | 120,800 | 1859 |

| Marbot | 140,000 | 160,000 | 1860 |

| Burton | 130,000 | 120,800 | 1914 |

| Garniich | 130,665 | 119,300 | 1956 |

| Tarle | 130,000 | 127,800 | 1962 |

| Grunward | 130,000 | 120,000 | 1963 |

| Beskrovny | 135,000 | 126,000 | 1968 |

| Chandler | 156,000 | 120,800 | 1966 |

| Thiry | 120,000 | 133,000 | 1969 |

| Holmes | 130,000 | 120,800 | 1971 |

| Duffy | 133,000 | 125,000 | 1972 |

| Tranie | 127,000 | 120,000 | 1981 |

| Nicolson | 128,000 | 106,000 | 1985 |

| Troitsky | 134,000 | 154,800 | 1988 |

| Vasiliev | 130,000 | 155,200 | 1997 |

| Smith | 133,000 | 120,800 | 1998 |

| Zemtsov | 127,000 | 154,000 | 1999 |

| Hourtoulle | 115,000 | 140,000 | 2000 |

| Bezotosny | 135,000 | 150,000 | 2004 |

| Dwyer | 113,000-135,00 | 125,000-155,000 | 2013 |

| Roberts | 103,000 | 120,800 | 2015 |

It is not unusual for a pivotal battle of this era to be difficult to document. Similar difficulties exist with the Battle of Waterloo or battles of the War of 1812 in North America, while the Battle of Borodino offers its own particular challenges to accuracy. It has been repeatedly subjected to overtly political uses.

Personal accounts of the battle frequently magnified an individual’s own role or minimised those of rivals. The politics of the time were complex and complicated by ethnic divisions between native Russian nobility and those having second and third-generation German descent, leading to rivalry for positions in command of the army. Not only does a historian have to deal with the normal problem of a veteran looking back and recalling events as he or she would have liked them to have been, but in some cases outright malice was involved. Nor was this strictly a Russian event, as bickering and sabotage were known amongst the French marshals and their reporting generals. To «lie like a bulletin» was a recognised phrase amongst his troops.[b] It was not just a French affair either, with Kutuzov in particular promoting an early form of misinformation that has continued to this day. Further distortions occurred during the Soviet years, when an adherence to a «formula» was the expectation during the Stalin years and for some time after that. The over-reliance of western histories on the battle and of the campaign on French sources has been noted by later historians.

The views of historians of the outcome of the battle changed with the passage of time and the changing political situations surrounding them. Kutuzov proclaimed a victory both to the army and to Emperor Alexander. While many a general throughout history claimed victory out of defeat (Ramses II of Egypt did so) and in this case, Kutuzov was commander-in-chief of the entire Russian army, and it was an army that, despite the huge losses, considered itself undefeated. Announcing a defeat would have removed Kutuzov from command, and damaged the morale of the proud soldiers. While Alexander was not deceived by the announcement, it gave him the justification needed to allow Kutuzov to march his army off to rebuild the Russian forces and later complete the near utter destruction of the French army. As such, what was said by Kutuzov and those supporting his views was allowed to pass into the histories of the time unchecked.

Histories during the Soviet era raised the battle to a mythic contest with serious political overtones and had Kutuzov as the master tactician on the battlefield, directing every move with the precision of a ballet master directing his troupe. Kutuzov’s abilities on the battlefield were, in the eyes of his contemporaries and fellow Russian generals, far more complex and often described in less than flattering terms. Noted author and historian David G. Chandler writing in 1966, echoes the Soviet era Russian histories in more than a few ways, asserting that General Kutuzov remained in control of the battle throughout, ordered counter-moves to Napoleon’s tactics personally rather than Bagration and Barclay doing so and put aside personal differences to overcome the dispositional mistakes of the Russian army. Nor is the tent scene played out; instead Kutuzov remains with the army. Chandler also has the Russian army in much better shape moving to secondary prepared positions and seriously considering attacking the next day.[62] Later historians Riehn and Mikaberidze have Kutuzov leaving most of the battle to Bagration and Barclay de Tolly, leaving early in the afternoon and relaying orders from his camp 30 minutes from the front.

His dispositions for the battle are described as a clear mistake leaving the right far too strong and the left much too weak. Only the fact that Bagration and Barclay were to cooperate fully saved the Russian army and did much to mitigate the bad positioning. Nothing would be more damning than 300 artillery pieces standing silent on the Russian right.

Casualties[edit]

The fighting involved around 250,000 troops and left at least 68,000 killed and wounded, making Borodino the deadliest day of the Napoleonic Wars and the bloodiest single day in the history of warfare until the First Battle of the Marne in 1914.

The casualties of the battle were staggering: according to French General Staff Inspector P. Denniee, the Grande Armée lost approximately 28,000 soldiers: 6,562 (including 269 officers) were reported as dead, 21,450 as wounded. But according to French historian Aristid Martinien, at least 460 French officers (known by name) were killed in battle. In total, the Grande Armée lost 1,928 officers dead and wounded, including 49 generals. The list of slain included French Generals of Division Auguste-Jean-Gabriel de Caulaincourt, Louis-Pierre Montbrun, Jean Victor Tharreau and Generals of Brigade Claude Antoine Compère, François Auguste Damas, Léonard Jean Aubry Huard de Saint-Aubin, Jean Pierre Lanabère, Charles Stanislas Marion, Louis Auguste Marchand Plauzonne, and Jean Louis Romeuf.

Suffering a wound on the Borodino battlefield was effectively a death sentence, as French forces did not possess enough food for the healthy, much less the sick; consequently, equal numbers of wounded soldiers starved to death, died of their injuries, or perished through neglect. The casualties were for a single day of battle, while the Russian figures are for the 5th and the 7th, combined. Using the same accounting method for both armies brings the actual French Army casualty count to 34,000–35,000.

The Russians suffered terrible casualties during the fighting, losing over a third of their army. Some 52,000 Russian troops were reported as dead, wounded or missing, including 1,000 prisoners; some 8,000 men were separated from their units and returned over the next few days, bringing the total Russian losses to 44,000. Twenty-two Russian generals were killed or wounded, including Prince Bagration, who died of his wounds on 24 September. Historian Gwynne Dyer compared the carnage at Borodino to «a fully-loaded 747 crashing, with no survivors, every 5 minutes for eight hours.» Taken as a one-day battle in the scope of the Napoleonic conflict, this was the bloodiest battle of this series of conflicts with combined casualties between 72,000 and 73,000. The next nearest battle would be Waterloo, at about 55,000 for the day.

In the historiography of this battle, the figures would be deliberately inflated or underplayed by the generals of both sides attempting to lessen the impact the figures would have on public opinion both during aftermath of the battle or, for political reasons, later during the Soviet period.

Aftermath[edit]

Attrition warfare[edit]

The Battle of Borodino was a victory for Napoleon, as the Russian army retreated to the south of Moscow and the French army occupied Moscow. The next major conventional battle was the Battle of Tarutino about five weeks later. After «delayed operation» in his attrition warfare Kutuzov used scorched earth strategy by burning Moscow’s resources, guerrilla warfare by the Cossacks against any kind of transport and total war by the peasants against foraging. This kind of warfare weakened the French army at its most vulnerable point: logistics, as it was unable to pillage Russian land, which was insufficiently populated nor cultivated, meaning that starvation became the most dangerous enemy long before the cold joined in.

The feeding of horses by supply trains was extremely difficult, as a ration for a horse weighs about ten times as much as one for a man. It was tried in vain to feed and water all the horses by foraging expeditions.

Pyrrhic victory[edit]

Some scholars and contemporaries described Borodino as a Pyrrhic victory. Russian historian Oleg Sokolov posits that Borodino constituted a Pyrrhic victory for the French, which would ultimately cost Napoleon the war and his crown, although at the time none of this was apparent to either side. Sokolov adds that the decision to not commit the Guard saved the Russians from an Austerlitz-style defeat and quotes Marshal Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, one of Napoleon’s finest strategists, who analyzed the battle and concluded that an intervention of the Guard would have torn the Russian army to pieces and allowed Napoleon to safely follow his plans to take winter quarters in Moscow and resume his successful campaign in spring or offer the Tsar acceptable peace terms. Digby Smith calls Borodino ‘a draw’ but believes that posterity proved Napoleon right in his decision to not commit the Guard so far away from his homeland. According to Christopher Duffy, the battle of Borodino could be seen as a new Battle of Torgau, in which both of the sides sustained terrible losses but neither could achieve their tactical goals, and the battle itself did not have a clear result, although both sides claimed the battle as their own victory.

However, in what had become a war of attrition, the battle was just one more source of losses to the French when they were losing two men to one. Both the French and the Russians suffered terribly but the Russians had reserve troops, and a clear logistical advantage. The French Army supplies came over a long road lined with hostile forces. According to Riehn, so long as the Russian Army existed the French continued to lose.

This victory of Napoleon was not decisive, but it allowed the French emperor to occupy Moscow to await a surrender that would never come. The capture of Moscow proved a Pyrrhic victory, since the Russians had no intention of negotiating with Napoleon for peace. Historian Riehn notes that the Borodino victory allowed Napoleon to move on to Moscow, where—even allowing for the arrival of reinforcements—the French Army only possessed a maximum of 95,000 men, who would be ill-equipped to win a battle due to a lack of supplies and ammunition. The main part of the Grande Armée suffered more than 90,000 casualties by the time of the Moscow retreat, see Minard’s map; typhus, dysentery, starvation and hypothermia ensured that only about 10,000 men of the main force returned across the Russian border alive. Furthermore, although the Russian army suffered heavy casualties in the battle, it regrouped by the time of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow; it soon began to interfere with the French withdrawal and made it a catastrophe.

Legacy[edit]

Historical reenactment of 1812 battle near Borodino, 2011

1987 Soviet commemorative coin, reverse

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky also composed his 1812 Overture to commemorate the battle.

The battle was famously described by Leo Tolstoy in his novel War and Peace: «After the shock that had been received, the French army was still able to crawl to Moscow; but there, without any new efforts on the part of the Russian troops, it was doomed to perish, bleeding to death from the mortal wound received at Borodino.»

Poet Mikhail Lermontov romanticized the battle in his poem Borodino.[87]

A huge panorama representing the battle was painted by Franz Roubaud for the centenary of Borodino and installed on the Poklonnaya Hill in Moscow to mark the 150th anniversary of the event.

In Russia, the Battle of Borodino is reenacted yearly on the first Sunday of September.

On the battlefield itself, the Bagration flèches are preserved; a modest monument has been constructed in honour of the French soldiers who fell in the battle.

A commemorative 1-ruble coin was released in the Soviet Union in 1987 to commemorate the 175th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino, and four million were minted.[88]

A minor planet 3544 Borodino, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1977 was named after the village of Borodino.

From May 1813 to the present, at least 29 ships have been named Borodino after the battle (see list of ships named Borodino), and many others after participants in the battle: 24 ships in honor of Mikhail Kutuzov, 18 ships in honor of Matvei Platov, 15 ships in honor of Pyotr Bagration, 33 ships in honor of the Cossacks, 4 ships in honor of Denis Davydov, two ships each in honor of Louis-Alexandre Berthier, Jean-Baptiste Bessières and Michel Ney; and one ship each in honor of the officers of the Marine Guards crew I.P. Kartsov, N.P. Rimsky-Korsakov and M.N. Lermontov; Prince Vorontsov, generals Yermolov and Raevsky, Marshal of the Empire Louis-Nicolas Davout.

See also[edit]

- Military career of Napoleon Bonaparte

- Nikolay Vuich

- Ivan Shevich

- Andrei Miloradovich

- Avram Ratkov

- Ivan Adamovich

- Nikolay Bogdanov

- Ilya Duka

- Georgi Emmanuel

- Peter Ivelich

Explanatory Notes[edit]

- ^ Russian: Бopoди́нcкoe cpaже́ниe, tr. Borodínskoye srazhéniye; French: Bataille de la Moskova.

- ^ Napoleon was in the habit of issuing regular bulletins describing his campaigns.

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- Bell, David Avrom (2007). The First Total War: Napoleon’s Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It. Houghton, Mifflin and company.

- Chambray, George de (1823). Histoire de l’expédition de Russie. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Chandler, David G. (1999). Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Ware, UK: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-84022-203-6.

- Chandler, David; Nafziger, George F. (1988). Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia. Novato CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-89141-661-6.

- Clausewitz, Carl von (1873). On War. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- (in French) Denniee, P. (1842). Itineraire de l’Empereur Napoleon.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (2006). Napoleon; a History of the Art of War: From the beginning of the Peninsular war to the end of the Russian campaign, with a detailed account of the Napoleonic wars.