Движение луддитов в Англии

4.8

Средняя оценка: 4.8

Всего получено оценок: 139.

Обновлено 22 Декабря, 2021

4.8

Средняя оценка: 4.8

Всего получено оценок: 139.

Обновлено 22 Декабря, 2021

Движение луддитов в Англии стало следствием начавшейся в 18 веке промышленной революции, сопровождавшейся вытеснением мануфактуры фабрикой. Оно пришлось на правление короля Георга III, который занимал престол с 1760 по 1820 год. Участники движения луддитов ломали станки, так как считали, что из-за внедрения в производство машин снижается доля занятых.

Начало движения и его особенности

Основателем движения считается рабочий-ткач Нед Лудд. Скорее всего, он был вымышленной фигурой и стал народным героем, как Робин Гуд на несколько веков ранее.

Известно, что в 1779 году он сломал два станка, но датой начала движения луддитов стал конец 1811 года. Рабочие, которые ломали станки, считали своим идейным предводителем Лудда и даже называли его генералом.

Вопрос о причинах действий луддитов до сих пор остаётся открытым. Ряд историков считают, что они хотели с помощью таких действий договориться с работодателями, которые нанимали менее квалифицированных и менее оплачиваемых рабочих для обслуживания новых станков. Особенностью движения луддитов является отсутствие политической организации.

Условия труда на фабриках Англии в начале XIX века были суровыми, но эффективность предприятий была высокой из-за использования текстильных станков, то есть новых технологий. Благодаря техническому прогрессу текстиль становился дешевле, а Великобритания стала первой экономикой мира до конца века.

Действия луддитов и властей

Основным очагом движения стало графство Ноттингемшир, но в начале 1812 года оно перекинулось на Йоркшир и Ланкашир. Суть тактики луддитов заключалась в том, что они собирались по ночам вблизи крупных промышленных центров и создавали отряды, в которых шла строевая подготовка.

Луддиты занимались не только индустриальным саботажем. Им приходилось вступать в бой с правительственными войсками и нападать на владельцев фабрик. В ряде случаев они ограничивались отправкой писем с угрозами.

С 1813 года власти ввели смертную казнь за уничтожение станков. Известно, что было повешено 17 человек. Некоторых пойманных луддитов отправляли на каторгу в Австралию. Отдельные случаи луддизма были зафиксированы в 1816 году, а затем и в 1817, когда безработный чулочный мастер Иеремия Брандрет организовал народное выступление в графстве Дербишир. Оно уже не было связано с уничтожением машин.

Движение луддитов совпало с войной шестой коалиции против Наполеона в 1813–1814 годах. Часть британской армии пришлось задействовать против луддитов. Итогом движения стал его разгром властями, а также появление термина «луддизм», а затем и «неолуддизм». Так называют критиков инноваций и научно-технического прогресса.

Что мы узнали?

Движение луддитов существовало в Англии краткий период с 1811 по 1813 год. Оно стало примером того, как технические новинки вошли в противоречие с интересами той части общества, которая хотела сохранения старых порядков.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Никита Червоненко

4/5

Оценка доклада

4.8

Средняя оценка: 4.8

Всего получено оценок: 139.

А какая ваша оценка?

- Взрослым: Skillbox, Хекслет, Eduson, XYZ, GB, Яндекс, Otus, SkillFactory.

- 8-11 класс: Умскул, Лектариум, Годограф, Знанио.

- До 7 класса: Алгоритмика, Кодланд, Реботика.

- Английский: Инглекс, Puzzle, Novakid.

1810-е. Движение луддитов в Англии

Промышленная революция в Англии спровоцировала быстрый экономический рост, но для населения массовое применение машин обернулось массовой безработицей, падением доходов и ростом цен на продовольствие. В первой четверти XIX века появилась форма протеста против механизации промышленности — рабочее движение луддитов, которые выражали свое недовольство погромами на мануфактурах и порчей станков.

Промышленная революция в Англии

К началу XIX века Англия благодаря техническому перевороту в промышленности была наиболее экономически развитым государством в мире. Легкая промышленность, особенно текстильная, а затем тяжелая промышленность развивались быстрыми темпами за счет расширения рынков сбыта, причиной чего были рост населения и войны. Наконец, развитие науки также сказывалось на промышленном производстве.

В промышленности широко внедрялись машины. В 1769 году Д. Уаттом был усовершенствован паровой двигатель, изобретенный задолго до этого. Уже в конце XVIII века он стал основой для высокопроизводительного ткацкого станка, что резко увеличило спрос на топливо и сырье, а затем обусловило технический переворот в смежных отраслях. Увеличение количества вводимых в строй машин, крупные правительственные заказы на вооружение армии и флота, а также рост железнодорожного и морского транспорта привели к развитию металлургии.

В 1810 году в Англии насчитывалось около 5 тысяч паровых машин в разных отраслях промышленности и ежегодно их количество в среднем увеличивалось еще на тысячу. Повсеместно появлялись заводы и фабрики. В промышленности страны была занята почти половина населения — это были прежде всего рабочие и мелкие ремесленники, но быстро росло число и индустриальных рабочих, которые в итоге сформировали массовый рабочий класс.

Формирование рабочего движения

Усовершенствование технического оснащения заводов, экспорт в другие страны — все это требовало огромных расходов. Хозяева фабрик, стараясь снизить цену на продукцию, экономили на заработной плате и условиях труда рабочих. Последним идти было некуда, так как механизация вызвала разорение ремесленников и мелких промышленников, поэтому они вынуждены были соглашаться на предлагаемые условия.

Рабочие были поставлены на грань выживания, ради заработка на фабрики выходили жены и дети рабочих, хотя их труд оплачивался гораздо ниже. В начале XIX века рабочих-мужчин старше 18 лет на заводах было лишь 27%, остальные фабричные рабочие были женщинами и детьми.

Несмотря на нескончаемую работу, большая часть населения жила в нищете. Рост стоимости жизни опережал рост зарплат рабочих, цены на продовольствие повышались, в стране было огромное количество демобилизованных солдат и разорившихся ремесленников, теперь оставшихся без работы и средства заработка.

В итоге промышленные рабочие начали объединяться для защиты собственных интересов. Первым рабочим движением стал луддизм на мануфактурах Средней и Северной Англии.

Луддиты

В своем бедственном положении рабочие винили машины, с появлением которых они связывали низкие зарплаты, безработицу и неуважительное отношение хозяев к своему труду. Не меньшее недовольство вызывала политика правительства, которое не предпринимало никаких мер для улучшения ситуации.

Согласно легенде, один из рабочих ткацкой фабрики по имени Нед Лудд (его реальность не доказана) первым сломал чулочные станки — отсюда пошло и название движения. Пик активности луддитов пришелся на 1811-1813 гг, и первыми от них пострадали шерстяные и хлопкообрабатывающие фабрики. По стране распространялись слухи о том, что рабочие намерены уничтожить все мануфактуры и вернуть использование в промышленности ручного труда.

В ноябре 1811 года вспыхнуло восстание луддитов в Ноттингемшире, в начале 1812 года — в Йоркшире и Ланкашире. От нападений страдали не только фабрики, но и члены городской администрации вместе с торговцами, которых обвиняли в завышении цен.

Впрочем, луддиты не походили на стихийную толпу, которая крушила все на своем пути. Их нападения были бескровны и отлично организованы. Судебные отчеты содержат информацию о том, что в ноябре 1811 года рабочие прежде прислали хозяину фабрики предупреждение с указанием сроков, когда они придут и потребуют выдачи станков. Предприниматель успел вооружить слуг, но луддиты все же выломали дверь и осуществили задуманное.

Конец движения

Для контроля над рабочими в разгар движения луддитов в промышленных районах было размещено до 12 тысяч солдат британской регулярной армии. Однако это не могло полностью поправить положение, так как взять под охрану все мастерские и станки в них было физически невозможно.

Происходящее вынудило правительство принять репрессивные законы для борьбы с порчей станков. 20 марта 1812 года был принят временный акт, согласно которому за намеренное разрушение машин (индустриальный саботаж) полагалась смертная казнь. В соответствии с этим законом было повешено 17 луддитов, еще несколько сотен было выслано в Австралию.

Со временем движение луддитов изменило характер. Его участники стали больше походить на боевые отряды, с которыми властям было проще бороться, в том числе за счет внедрения доносчиков и провокаторов. Погромы станков превращались в ограбления продуктовых лавок, что сильно вредило луддитам в общественном мнении.

Жесткая политика центральной администрации, запрет на создание профессиональных союзов в 1824 году вкупе с мерами по улучшению экономического положения рабочих принесли свои плоды и движение постепенно затухло.

- Взрослым: Skillbox, Хекслет, Eduson, XYZ, GB, Яндекс, Otus, SkillFactory.

- 8-11 класс: Умскул, Лектариум, Годограф, Знанио.

- До 7 класса: Алгоритмика, Кодланд, Реботика.

- Английский: Инглекс, Puzzle, Novakid.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Not to be confused with Ludites.

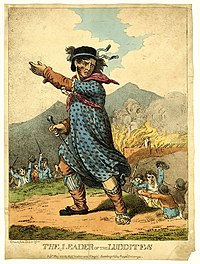

The Leader of the Luddites, 1812. Hand-coloured etching.

The Luddites were a secret oath-based organisation[1] of English textile workers in the 19th century who formed a radical faction which destroyed textile machinery. The group is believed to have taken its name from Ned Ludd, a legendary weaver supposedly from Anstey, near Leicester. They protested against manufacturers who used machines in what they called «a fraudulent and deceitful manner» to get around standard labour practices.[2] Luddites feared that the time spent learning the skills of their craft would go to waste, as machines would replace their role in the industry.[3]

Many Luddites were owners of workshops that had closed because factories could sell similar products for less. But when workshop owners set out to find a job at a factory, it was very hard to find one because producing things in factories required fewer workers than producing those same things in a workshop. This left many people unemployed and angry.[4]

The Luddite movement began in Nottingham in England and culminated in a region-wide rebellion that lasted from 1811 to 1816.[5] Mill and factory owners took to shooting protesters and eventually the movement was suppressed with legal and military force, which included execution and penal transportation of accused and convicted Luddites.[6]

Over time, the term has come to mean one opposed to industrialisation, automation, computerisation, or new technologies in general.[7]

Etymology[edit]

The name Luddite () is of uncertain origin. The movement was said to be named after Ned Ludd, an apprentice who allegedly smashed two stocking frames in 1779 and whose name had become emblematic of machine destroyers. Ned Ludd, however, was probably completely fictional and used as a way to shock and provoke the government.[8][9][10] The name developed into the imaginary General Ludd or King Ludd, who was reputed to live in Sherwood Forest like Robin Hood.[11][a]

‘Lud’ or ‘Ludd’ (Welsh: Lludd map Beli Mawr), according to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s legendary History of the Kings of Britain and other medieval Welsh texts, was a Celtic King of ‘The Islands of Britain’ in pre-Roman times, who supposedly founded London and was buried at Ludgate.[14] In the Welsh versions of Geoffrey’s Historia, usually called Brut y Brenhinedd, he is called Lludd fab Beli, establishing the connection to the early mythological Lludd Llaw Eraint.[15]

Historical precedents[edit]

In 1779, Ned Ludd, a weaver from Anstey, near Leicester, England, is supposed to have broken two stocking frames in a fit of rage. When the «Luddites» emerged in the 1810s, his identity was appropriated to become the folkloric character of Captain Ludd, also known as King Ludd or General Ludd, the Luddites’ alleged leader and founder.

The lower classes of the 18th century were not openly disloyal to the king or government, generally speaking,[16] and violent action was rare because punishments were harsh. The majority of individuals were primarily concerned with meeting their own daily needs.[17] Working conditions were harsh in the English textile mills at the time, but efficient enough to threaten the livelihoods of skilled artisans.[18] The new inventions produced textiles faster and cheaper because they were operated by less-skilled, low-wage labourers, and the Luddite goal was to gain a better bargaining position with their employers.[19]

Kevin Binfield asserts that organized action by stockingers had occurred at various times since 1675, and he suggests that the movements of the early 19th century should be viewed in the context of the hardships suffered by the working class during the Napoleonic Wars, rather than as an absolute aversion to machinery.[20][21][22] Irregular rises in food prices provoked the Keelmen to riot in the port of Tyne in 1710[23] and tin miners to steal from granaries at Falmouth in 1727. There was a rebellion in Northumberland and Durham in 1740, and an assault on Quaker corn dealers in 1756. Skilled artisans in the cloth, building, shipbuilding, printing, and cutlery trades organized friendly societies to peacefully insure themselves against unemployment, sickness, and intrusion of foreign labour into their trades, as was common among guilds.[24][b]

Malcolm L. Thomis argued in his 1970 history The Luddites that machine-breaking was one of a very few tactics that workers could use to increase pressure on employers, to undermine lower-paid competing workers, and to create solidarity among workers. «These attacks on machines did not imply any necessary hostility to machinery as such; machinery was just a conveniently exposed target against which an attack could be made.»[22] An agricultural variant of Luddism occurred during the widespread Swing Riots of 1830 in southern and eastern England, centering on breaking threshing machines.[25]

Birth of the movement[edit]

- See also Barthélemy Thimonnier, whose sewing machines were destroyed by tailors who believed that their jobs were threatened

Handloom weavers burned mills and pieces of factory machinery. Textile workers destroyed industrial equipment during the late 18th century,[2] prompting acts such as the Protection of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1788.

The Luddite movement emerged during the harsh economic climate of the Napoleonic Wars, which saw a rise of difficult working conditions in the new textile factories. Luddites objected primarily to the rising popularity of automated textile equipment, threatening the jobs and livelihoods of skilled workers as this technology allowed them to be replaced by cheaper and less skilled workers.[2][failed verification] The movement began in Arnold, Nottingham, on 11 March 1811 and spread rapidly throughout England over the following two years.[26][2] The British economy suffered greatly in 1810 to 1812, especially in terms of high unemployment and inflation. The causes included the high cost of the wars with Napoleon, Napoleon’s Continental System of economic warfare, and escalating conflict with the United States. The crisis led to widespread protest and violence, but the middle classes and upper classes strongly supported the government, which used the army to suppress all working class unrest, especially the Luddite movement.[27][28]

The Luddites met at night on the moors surrounding industrial towns to practice military-like drills and manoeuvres. Their main areas of operation began in Nottinghamshire in November 1811, followed by the West Riding of Yorkshire in early 1812, and then Lancashire by March 1813. They smashed stocking frames and cropping frames among other things. There does not seem to have been any political motivation behind the Luddite riots and there was no national organization; the men were merely attacking what they saw as the reason for the decline in their livelihoods.[29] Luddites clashed with government troops at Burton’s Mill in Middleton and at Westhoughton Mill, both in Lancashire.[30] The Luddites and their supporters anonymously sent death threats to, and possibly attacked, magistrates and food merchants. Activists smashed Heathcote’s lacemaking machine in Loughborough in 1816.[31] He and other industrialists had secret chambers constructed in their buildings that could be used as hiding places during an attack.[32]

In 1817, an unemployed Nottingham stockinger and probably ex-Luddite, named Jeremiah Brandreth led the Pentrich Rising. While this was a general uprising unrelated to machinery, it can be viewed as the last major Luddite act.[33]

Government response[edit]

The British government ultimately dispatched 12,000 troops to suppress Luddite activity, which as historian Eric Hobsbawm noted was a larger number than the army which the Duke of Wellington led during the Peninsular War.[34][c] Four Luddites, led by a man named George Mellor, ambushed and assassinated mill owner William Horsfall of Ottiwells Mill in Marsden, West Yorkshire, at Crosland Moor in Huddersfield. Horsfall had remarked that he would «Ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood».[35] Mellor fired the fatal shot to Horsfall’s groin, and all four men were arrested. One of the men, Benjamin Walker, turned informant, and the other three were hanged.[36][37][38] Lord Byron denounced what he considered to be the plight of the working class, the government’s inane policies and ruthless repression in the House of Lords on 27 February 1812: «I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey; but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return, in the very heart of a Christian country».[39]

Government officials sought to suppress the Luddite movement with a mass trial at York in January 1813, following the attack on Cartwrights Mill at Rawfolds near Cleckheaton. The government charged over 60 men, including Mellor and his companions, with various crimes in connection with Luddite activities. While some of those charged were actual Luddites, many had no connection to the movement. Although the proceedings were legitimate jury trials, many were abandoned due to lack of evidence and 30 men were acquitted. These trials were certainly intended to act as show trials to deter other Luddites from continuing their activities. The harsh sentences of those found guilty, which included execution and penal transportation, quickly ended the movement.[6][40] Parliament made «machine breaking» (i.e. industrial sabotage) a capital crime with the Frame Breaking Act of 1812.[41] Lord Byron opposed this legislation, becoming one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites after the treatment of the defendants at the York trials.[42]

Legacy[edit]

In the 19th century, occupations that arose from the growth of trade and shipping in ports, also in «domestic» manufacturers, were notorious for precarious employment prospects. Underemployment was chronic during this period,[24] and it was common practice to retain a larger workforce than was typically necessary for insurance against labour shortages in boom times.[24]

Moreover, the organization of manufacture by merchant-capitalists in the textile industry was inherently unstable. While the financiers’ capital was still largely invested in raw material, it was easy to increase commitment where trade was good and almost as easy to cut back when times were bad. Merchant-capitalists lacked the incentive of later factory owners, whose capital was invested in building and plants, to maintain a steady rate of production and return on fixed capital. The combination of seasonal variations in wage rates and violent short-term fluctuations springing from harvests and war produced periodic outbreaks of violence.[24]

Modern usage[edit]

Nowadays, the term «Luddite» often is used to describe someone who is opposed or resistant to new technologies.[43]

In 1956, during a British Parliamentary debate, a Labour spokesman said that «organised workers were by no means wedded to a ‘Luddite Philosophy’.»[44] By 2006, the term neo-Luddism had emerged to describe opposition to many forms of technology.[45] According to a manifesto drawn up by the Second Luddite Congress (April 1996; Barnesville, Ohio), neo-Luddism is «a leaderless movement of passive resistance to consumerism and the increasingly bizarre and frightening technologies of the Computer Age».[46]

The term «Luddite fallacy» is used by economists in reference to the fear that technological unemployment inevitably generates structural unemployment and is consequently macroeconomically injurious. If a technological innovation results in a reduction of necessary labour inputs in a given sector, then the industry-wide cost of production falls, which lowers the competitive price and increases the equilibrium supply point that, theoretically, will require an increase in aggregate labour inputs.[47] During the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, the dominant view among economists has been that belief in long-term technological unemployment was indeed a fallacy. More recently, there has been increased support for the view that the benefits of automation are not equally distributed.[48][49][50]

See also[edit]

- Development criticism

- Ted Kaczynski

- Ruddington Framework Knitters’ Museum – features a Luddite gallery

- Simple living

- Technophobia

- Turner Controversy – return to pre-industrial methods of production

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Historian Eric Hobsbawm has called their machine wrecking «collective bargaining by riot», which had been a tactic used in Britain since the Restoration because manufactories were scattered throughout the country, and that made it impractical to hold large-scale strikes.[12][13]

- ^ The Falmouth magistrates reported to the Duke of Newcastle (16 November 1727) that «the unruly tinners» had «broke open and plundered several cellars and granaries of corn.» Their report concludes with a comment which suggests that they were not able to understand the rationale of the direct action of the tinners: «the occasion of these outrages was pretended by the rioters to be a scarcity of corn in the county, but this suggestion is probably false, as most of those who carried off the corn gave it away or sold it at quarter price.» PRO, SP 36/4/22.

- ^ Hobsbawm has popularized this comparison and refers to the original statement in Frank Ongley Darvall (1934) Popular Disturbances and Public Order in Regency England, London, Oxford University Press, p. 260.

References[edit]

- ^ Byrne, Richard (August 2013). «A Nod to Ned Ludd». The Baffler. 23 (23): 120–128. doi:10.1162/BFLR_a_00183. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d Conniff, Richard (March 2011). «What the Luddites Really Fought Against». Smithsonian. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ «Who were the Luddites?». History.com. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ «Economix Comix». economixcomix.com. 25 June 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Linton, David (Fall 1992). «THE LUDDITES: How Did They Get That Bad Reputation?». Labor History. 33 (4): 529–537. doi:10.1080/00236569200890281. ISSN 0023-656X.

- ^ a b «Luddites in Marsden: Trials at York». Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ «Luddite»[dead link]. Compact Oxford English Dictionary at AskOxford.com. Accessed 22 February 2010.

- ^ Anstey at Welcome to Leicester (visitoruk.com) According to this source, «A half-witted Anstey lad, Ned Ludlam or Ned Ludd, gave his name to the Luddites, who in the 1800s followed his earlier example by expressing violence against machinery in protest against the Industrial Revolution.» It is a known theory that Ned Ludd was the group leader of the Luddites.

- ^ Palmer, Roy, 1998, The Sound of History: Songs and Social Comment, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-215890-1, p. 103

- ^ Chambers, Robert (2004), Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Part 1, Kessinger, ISBN 978-0-7661-8338-4, p. 357

- ^ «Power, Politics and Protest | the Luddites». Learning Curve. The National Archives. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Hobsbawm 1952, p. 59.

- ^ Autor, D. H.; Levy, F.; Murnane, R. J. (1 November 2003). «The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration». The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 118 (4): 1279–1333. doi:10.1162/003355303322552801. hdl:1721.1/64306. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010.

- ^ Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae 3.20

- ^ Rachel Bromwich (ed.), Trioedd Ynys Prydein (Cardiff, 1991; 1991), s.v. ‘Lludd fab Beli’.

- ^ Robert Featherstone Wearmouth (1945). Methodism and the common people of the eighteenth century. Epworth Press. p. 51. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ R. F. Wearmouth, Methodism and the Common People of the Eighteenth Century. (1945), esp. chs. 1 and 2.

- ^ Clancy, Brett (October 2017). «Rebel or Rioter? Luddites Then and Now». Society. 54 (5): 392–398. doi:10.1007/s12115-017-0161-6. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 148899583.

- ^ Merchant, Brian (2 September 2014). «You’ve Got Luddites All Wrong». Vice. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Binfield, Kevin (2004). Luddites and Luddism. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Rude, George (2001). The Crowd in History: A Study of Popular Disturbances in France and England, 1730–1848. Serif.

- ^ a b Thomis, Malcolm (1970). The Luddites: Machine Breaking in Regency England. Shocken.

- ^ «Historical events – 1685–1782 | Historical Account of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (pp. 47–65)». British History Online. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Charles Wilson, England’s Apprenticeship, 1603–1763 (1965), pp. 344–45. PRO, SP 36/4/22.

- ^ Harrison, J. F. C. (1984). The Common People: A History from the Norman Conquest to the Present. London, Totowa, N.J: Croom Helm. pp. 249–53. ISBN 0709901259. OL 16568504M.

- ^ Beckett, John. «Luddites». The Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway. Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Roger Knight, Britain Against Napoleon (2013), pp 410–412.

- ^ Francois Crouzet, Britain Ascendant (1990) pp 277–279.

- ^ «The Luddites 1811–1816». victorianweb.org. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Dinwiddy, J.R. (1992). «Luddism and Politics in the Northern Counties». Radicalism and Reform in Britain, 1780–1850. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 371–401. ISBN 9781852850623.

- ^ Sale 1995, p. 188.

- ^ «Workmen discover secret chambers». BBC News. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Summer D. Leibensperger, «Brandreth, Jeremiah (1790–1817) and the Pentrich Rising.» The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (2009): 1–2.

- ^ Hobsbawm 1952, p. 58: «The 12,000 troops deployed against the Luddites greatly exceeded in size the army which Wellington took into the Peninsula in 1808.»

- ^ Sharp, Alan (4 May 2015). Grim Almanac of York. The History Press. ISBN 9780750964562.

- ^ Murder of William Horsfall – Newspaper report on the murder of William Horsfall

- ^ Huddersfield Exposed – William Horsfall (1770–1812).

- ^ «8th January 1813: The execution of George Mellor, William Thorpe & Thomas Smith». The Luddite Bicentenary – 1811–1817. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2020 – via ludditebicentenary.blogspot.com.

- ^ Lord Byron, Debate on the 1812 Framework Bill, Hansard, http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/1812/feb/27/frame-work-bill#S1V0021P0_18120227_HOL_7

- ^ Elizabeth Gaskell: The Life of Charlotte Bronte, Vol. 1, Ch. 6, for contemporaneous description of attack on Cartwright.

- ^ «Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1812» at books.google.com

- ^ «Lord Byron and the Luddites | The Socialist Party of Great Britain». worldsocialism.org. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ «Luddite Definition & Meaning | Dictionary.com».

- ^ Sale 1995, p. 205.

- ^ Jones 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (1 February 1997). «America’s New Luddites». Le Monde diplomatique. Archived from the original on 30 June 2002.

- ^ Jerome, Harry (1934). Mechanization in Industry, National Bureau of Economic Research. pp. 32–35.

- ^

Krugman, Paul (12 June 2013). «Sympathy for the Luddites». The New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2015. - ^ Ford 2009, Chpt 3, ‘The Luddite Fallacy’

- ^ Lord Skidelsky (12 June 2013). «Death to Machines?». Project Syndicate. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

Sources[edit]

- Ford, Martin R. (2009), The Lights in the Tunnel: Automation, Accelerating Technology and the Economy of the Future, Acculant Publishing, ISBN 978-1448659814. (e-book available free online.)

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, Gary M., and Robert D. Tollison. «Luddism as cartel enforcement.» Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft 142.4 (1986): 727–738. JSTOR 40750927.

- Archer, John E. (2000). «Chapter 4: Industrial Protest». Social unrest and popular protest in England, 1780–1840. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57656-7.

- Bailey, Brian J (1998). The Luddite Rebellion. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-1335-1.

- Darvall, F. Popular Disturbances and Public Order in Regency England (Oxford University Press, 1934)

- Dinwiddy, John. «Luddism and politics in the northern counties.» Social History 4.1 (1979): 33–63.

- Fox, Nicols (2003). Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite History in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-860-5.

- Grint, Keith & Woolgar, Steve (1997). «The Luddites: Diablo ex Machina«. The machine at work: technology, work, and organization. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-7456-0924-9.

- Haywood, Ian. «Unruly People: The Spectacular Riot.» in Bloody Romanticism (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2006) pp. 181–222.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (1952). «The Machine Breakers». Past & Present. 1 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1093/past/1.1.57.

- Horn, Jeff. «Machine-Breaking and the ‘Threat from Below’ in Great Britain and France during the Early Industrial Revolution.» in Crowd actions in Britain and France from the middle ages to the modern world (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2015) pp. 165–178.

- Jones, Steven E. (2006). Against technology: from the Luddites to Neo-Luddism. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-97868-2.

- Linebaugh, Peter. Ned Ludd & Queen Mab: machine-breaking, romanticism, and the several commons of 1811-12 (PM Press, 2012).

- Linton, David. «The Luddites: How did they get that bad reputation?» Labor History 33.4 (1992): 529–537. doi:10.1080/00236569200890281.

- McGaughey, Ewan (2018). «Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy». ssrn.com. SSRN 3044448.

- Munger, Frank. «Suppression of Popular Gatherings in England, 1800–1830». American Journal of Legal History 25 (1981): 111+.

- Navickas, Katrina. «The search for ‘general Ludd’: The mythology of Luddism.» Social History 30.3 (2005): 281–295.

- O’Rourke, Kevin Hjortshøj, Ahmed S. Rahman, and Alan M. Taylor. «Luddites, the industrial revolution, and the demographic transition.» Journal of Economic Growth 18.4 (2013): 373–409. JSTOR 42635331.

- Pallas, Stephen J. «‘The Hell that Bigots Frame’: Queen Mab, Luddism, and the Rhetoric of Working-Class Revolution». Journal for the Study of Radicalism 12.2 (2018): 55–80. doi:10.14321/jstudradi.12.2.0055. JSTOR 10.14321/jstudradi.12.2.0055.

- Patterson, A. Temple. «Luddism, Hampden Clubs, and Trade Unions in Leicestershire, 1816–17.» English Historical Review 63.247 (1948): 170–188. online

- Poitras, Geoffrey. «The Luddite trials: Radical suppression and the administration of criminal justice». Journal for the Study of Radicalism 14.1 (2020): 121–166.

- Pynchon, Thomas (28 October 1984). «Is It O.k. to Be a Luddite?». The New York Times.

- Randall, Adrian (2002). Before the Luddites: Custom, Community and Machinery in the English Woollen Industry, 1776–1809. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89334-3.

- Rude, George (2005). «Chapter 5, Luddism». The crowd in History, 1730–1848. Serif. ISBN 978-1-897959-47-3.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick (1995). Rebels against the future: the Luddites and their war on the Industrial Revolution: lessons for the computer age. Basic Books. ISBN 0-201-40718-3.

- Stöllinger, Roman. «The Luddite rebellion: Past and present». wiiw Monthly Report 11 (2018): 6–11.

- Thomis, Malcolm I. The Luddites: Machine-Breaking in Regency England (Archon Books. 1970).

- Thompson, E. P. (1968). The Making of the English Working Class.

- Wasserstrom, Jeffrey. «‘Civilization’ and Its Discontents: The Boxers and Luddites as Heroes and Villains.» Theory and Society (1987): 675–707. JSTOR 657679.

Primary sources[edit]

- Binfield, Kevin (2004). Writings of the Luddites. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-7612-5.

External links[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Luddite.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luddism.

Look up Luddite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Luddite Bicentenary – Comprehensive chronicle of the Luddite uprisings

- The Luddite Link – Comprehensive historical resources for the original West Yorkshire Luddites, University of Huddersfield

- Luddism and the Neo-Luddite Reaction by Martin Ryder, University of Colorado at Denver School of Education

- The Luddites and the Combination Acts from the Marxists Internet Archive

- The Luddites (1988)—Thames Television drama-documentary about the West Riding Luddites.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Not to be confused with Ludites.

The Leader of the Luddites, 1812. Hand-coloured etching.

The Luddites were a secret oath-based organisation[1] of English textile workers in the 19th century who formed a radical faction which destroyed textile machinery. The group is believed to have taken its name from Ned Ludd, a legendary weaver supposedly from Anstey, near Leicester. They protested against manufacturers who used machines in what they called «a fraudulent and deceitful manner» to get around standard labour practices.[2] Luddites feared that the time spent learning the skills of their craft would go to waste, as machines would replace their role in the industry.[3]

Many Luddites were owners of workshops that had closed because factories could sell similar products for less. But when workshop owners set out to find a job at a factory, it was very hard to find one because producing things in factories required fewer workers than producing those same things in a workshop. This left many people unemployed and angry.[4]

The Luddite movement began in Nottingham in England and culminated in a region-wide rebellion that lasted from 1811 to 1816.[5] Mill and factory owners took to shooting protesters and eventually the movement was suppressed with legal and military force, which included execution and penal transportation of accused and convicted Luddites.[6]

Over time, the term has come to mean one opposed to industrialisation, automation, computerisation, or new technologies in general.[7]

Etymology[edit]

The name Luddite () is of uncertain origin. The movement was said to be named after Ned Ludd, an apprentice who allegedly smashed two stocking frames in 1779 and whose name had become emblematic of machine destroyers. Ned Ludd, however, was probably completely fictional and used as a way to shock and provoke the government.[8][9][10] The name developed into the imaginary General Ludd or King Ludd, who was reputed to live in Sherwood Forest like Robin Hood.[11][a]

‘Lud’ or ‘Ludd’ (Welsh: Lludd map Beli Mawr), according to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s legendary History of the Kings of Britain and other medieval Welsh texts, was a Celtic King of ‘The Islands of Britain’ in pre-Roman times, who supposedly founded London and was buried at Ludgate.[14] In the Welsh versions of Geoffrey’s Historia, usually called Brut y Brenhinedd, he is called Lludd fab Beli, establishing the connection to the early mythological Lludd Llaw Eraint.[15]

Historical precedents[edit]

In 1779, Ned Ludd, a weaver from Anstey, near Leicester, England, is supposed to have broken two stocking frames in a fit of rage. When the «Luddites» emerged in the 1810s, his identity was appropriated to become the folkloric character of Captain Ludd, also known as King Ludd or General Ludd, the Luddites’ alleged leader and founder.

The lower classes of the 18th century were not openly disloyal to the king or government, generally speaking,[16] and violent action was rare because punishments were harsh. The majority of individuals were primarily concerned with meeting their own daily needs.[17] Working conditions were harsh in the English textile mills at the time, but efficient enough to threaten the livelihoods of skilled artisans.[18] The new inventions produced textiles faster and cheaper because they were operated by less-skilled, low-wage labourers, and the Luddite goal was to gain a better bargaining position with their employers.[19]

Kevin Binfield asserts that organized action by stockingers had occurred at various times since 1675, and he suggests that the movements of the early 19th century should be viewed in the context of the hardships suffered by the working class during the Napoleonic Wars, rather than as an absolute aversion to machinery.[20][21][22] Irregular rises in food prices provoked the Keelmen to riot in the port of Tyne in 1710[23] and tin miners to steal from granaries at Falmouth in 1727. There was a rebellion in Northumberland and Durham in 1740, and an assault on Quaker corn dealers in 1756. Skilled artisans in the cloth, building, shipbuilding, printing, and cutlery trades organized friendly societies to peacefully insure themselves against unemployment, sickness, and intrusion of foreign labour into their trades, as was common among guilds.[24][b]

Malcolm L. Thomis argued in his 1970 history The Luddites that machine-breaking was one of a very few tactics that workers could use to increase pressure on employers, to undermine lower-paid competing workers, and to create solidarity among workers. «These attacks on machines did not imply any necessary hostility to machinery as such; machinery was just a conveniently exposed target against which an attack could be made.»[22] An agricultural variant of Luddism occurred during the widespread Swing Riots of 1830 in southern and eastern England, centering on breaking threshing machines.[25]

Birth of the movement[edit]

- See also Barthélemy Thimonnier, whose sewing machines were destroyed by tailors who believed that their jobs were threatened

Handloom weavers burned mills and pieces of factory machinery. Textile workers destroyed industrial equipment during the late 18th century,[2] prompting acts such as the Protection of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1788.

The Luddite movement emerged during the harsh economic climate of the Napoleonic Wars, which saw a rise of difficult working conditions in the new textile factories. Luddites objected primarily to the rising popularity of automated textile equipment, threatening the jobs and livelihoods of skilled workers as this technology allowed them to be replaced by cheaper and less skilled workers.[2][failed verification] The movement began in Arnold, Nottingham, on 11 March 1811 and spread rapidly throughout England over the following two years.[26][2] The British economy suffered greatly in 1810 to 1812, especially in terms of high unemployment and inflation. The causes included the high cost of the wars with Napoleon, Napoleon’s Continental System of economic warfare, and escalating conflict with the United States. The crisis led to widespread protest and violence, but the middle classes and upper classes strongly supported the government, which used the army to suppress all working class unrest, especially the Luddite movement.[27][28]

The Luddites met at night on the moors surrounding industrial towns to practice military-like drills and manoeuvres. Their main areas of operation began in Nottinghamshire in November 1811, followed by the West Riding of Yorkshire in early 1812, and then Lancashire by March 1813. They smashed stocking frames and cropping frames among other things. There does not seem to have been any political motivation behind the Luddite riots and there was no national organization; the men were merely attacking what they saw as the reason for the decline in their livelihoods.[29] Luddites clashed with government troops at Burton’s Mill in Middleton and at Westhoughton Mill, both in Lancashire.[30] The Luddites and their supporters anonymously sent death threats to, and possibly attacked, magistrates and food merchants. Activists smashed Heathcote’s lacemaking machine in Loughborough in 1816.[31] He and other industrialists had secret chambers constructed in their buildings that could be used as hiding places during an attack.[32]

In 1817, an unemployed Nottingham stockinger and probably ex-Luddite, named Jeremiah Brandreth led the Pentrich Rising. While this was a general uprising unrelated to machinery, it can be viewed as the last major Luddite act.[33]

Government response[edit]

The British government ultimately dispatched 12,000 troops to suppress Luddite activity, which as historian Eric Hobsbawm noted was a larger number than the army which the Duke of Wellington led during the Peninsular War.[34][c] Four Luddites, led by a man named George Mellor, ambushed and assassinated mill owner William Horsfall of Ottiwells Mill in Marsden, West Yorkshire, at Crosland Moor in Huddersfield. Horsfall had remarked that he would «Ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood».[35] Mellor fired the fatal shot to Horsfall’s groin, and all four men were arrested. One of the men, Benjamin Walker, turned informant, and the other three were hanged.[36][37][38] Lord Byron denounced what he considered to be the plight of the working class, the government’s inane policies and ruthless repression in the House of Lords on 27 February 1812: «I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey; but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return, in the very heart of a Christian country».[39]

Government officials sought to suppress the Luddite movement with a mass trial at York in January 1813, following the attack on Cartwrights Mill at Rawfolds near Cleckheaton. The government charged over 60 men, including Mellor and his companions, with various crimes in connection with Luddite activities. While some of those charged were actual Luddites, many had no connection to the movement. Although the proceedings were legitimate jury trials, many were abandoned due to lack of evidence and 30 men were acquitted. These trials were certainly intended to act as show trials to deter other Luddites from continuing their activities. The harsh sentences of those found guilty, which included execution and penal transportation, quickly ended the movement.[6][40] Parliament made «machine breaking» (i.e. industrial sabotage) a capital crime with the Frame Breaking Act of 1812.[41] Lord Byron opposed this legislation, becoming one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites after the treatment of the defendants at the York trials.[42]

Legacy[edit]

In the 19th century, occupations that arose from the growth of trade and shipping in ports, also in «domestic» manufacturers, were notorious for precarious employment prospects. Underemployment was chronic during this period,[24] and it was common practice to retain a larger workforce than was typically necessary for insurance against labour shortages in boom times.[24]

Moreover, the organization of manufacture by merchant-capitalists in the textile industry was inherently unstable. While the financiers’ capital was still largely invested in raw material, it was easy to increase commitment where trade was good and almost as easy to cut back when times were bad. Merchant-capitalists lacked the incentive of later factory owners, whose capital was invested in building and plants, to maintain a steady rate of production and return on fixed capital. The combination of seasonal variations in wage rates and violent short-term fluctuations springing from harvests and war produced periodic outbreaks of violence.[24]

Modern usage[edit]

Nowadays, the term «Luddite» often is used to describe someone who is opposed or resistant to new technologies.[43]

In 1956, during a British Parliamentary debate, a Labour spokesman said that «organised workers were by no means wedded to a ‘Luddite Philosophy’.»[44] By 2006, the term neo-Luddism had emerged to describe opposition to many forms of technology.[45] According to a manifesto drawn up by the Second Luddite Congress (April 1996; Barnesville, Ohio), neo-Luddism is «a leaderless movement of passive resistance to consumerism and the increasingly bizarre and frightening technologies of the Computer Age».[46]

The term «Luddite fallacy» is used by economists in reference to the fear that technological unemployment inevitably generates structural unemployment and is consequently macroeconomically injurious. If a technological innovation results in a reduction of necessary labour inputs in a given sector, then the industry-wide cost of production falls, which lowers the competitive price and increases the equilibrium supply point that, theoretically, will require an increase in aggregate labour inputs.[47] During the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, the dominant view among economists has been that belief in long-term technological unemployment was indeed a fallacy. More recently, there has been increased support for the view that the benefits of automation are not equally distributed.[48][49][50]

See also[edit]

- Development criticism

- Ted Kaczynski

- Ruddington Framework Knitters’ Museum – features a Luddite gallery

- Simple living

- Technophobia

- Turner Controversy – return to pre-industrial methods of production

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Historian Eric Hobsbawm has called their machine wrecking «collective bargaining by riot», which had been a tactic used in Britain since the Restoration because manufactories were scattered throughout the country, and that made it impractical to hold large-scale strikes.[12][13]

- ^ The Falmouth magistrates reported to the Duke of Newcastle (16 November 1727) that «the unruly tinners» had «broke open and plundered several cellars and granaries of corn.» Their report concludes with a comment which suggests that they were not able to understand the rationale of the direct action of the tinners: «the occasion of these outrages was pretended by the rioters to be a scarcity of corn in the county, but this suggestion is probably false, as most of those who carried off the corn gave it away or sold it at quarter price.» PRO, SP 36/4/22.

- ^ Hobsbawm has popularized this comparison and refers to the original statement in Frank Ongley Darvall (1934) Popular Disturbances and Public Order in Regency England, London, Oxford University Press, p. 260.

References[edit]

- ^ Byrne, Richard (August 2013). «A Nod to Ned Ludd». The Baffler. 23 (23): 120–128. doi:10.1162/BFLR_a_00183. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d Conniff, Richard (March 2011). «What the Luddites Really Fought Against». Smithsonian. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ «Who were the Luddites?». History.com. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ «Economix Comix». economixcomix.com. 25 June 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Linton, David (Fall 1992). «THE LUDDITES: How Did They Get That Bad Reputation?». Labor History. 33 (4): 529–537. doi:10.1080/00236569200890281. ISSN 0023-656X.

- ^ a b «Luddites in Marsden: Trials at York». Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ «Luddite»[dead link]. Compact Oxford English Dictionary at AskOxford.com. Accessed 22 February 2010.

- ^ Anstey at Welcome to Leicester (visitoruk.com) According to this source, «A half-witted Anstey lad, Ned Ludlam or Ned Ludd, gave his name to the Luddites, who in the 1800s followed his earlier example by expressing violence against machinery in protest against the Industrial Revolution.» It is a known theory that Ned Ludd was the group leader of the Luddites.

- ^ Palmer, Roy, 1998, The Sound of History: Songs and Social Comment, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-215890-1, p. 103

- ^ Chambers, Robert (2004), Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Part 1, Kessinger, ISBN 978-0-7661-8338-4, p. 357

- ^ «Power, Politics and Protest | the Luddites». Learning Curve. The National Archives. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Hobsbawm 1952, p. 59.

- ^ Autor, D. H.; Levy, F.; Murnane, R. J. (1 November 2003). «The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration». The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 118 (4): 1279–1333. doi:10.1162/003355303322552801. hdl:1721.1/64306. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010.

- ^ Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae 3.20

- ^ Rachel Bromwich (ed.), Trioedd Ynys Prydein (Cardiff, 1991; 1991), s.v. ‘Lludd fab Beli’.

- ^ Robert Featherstone Wearmouth (1945). Methodism and the common people of the eighteenth century. Epworth Press. p. 51. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ R. F. Wearmouth, Methodism and the Common People of the Eighteenth Century. (1945), esp. chs. 1 and 2.

- ^ Clancy, Brett (October 2017). «Rebel or Rioter? Luddites Then and Now». Society. 54 (5): 392–398. doi:10.1007/s12115-017-0161-6. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 148899583.

- ^ Merchant, Brian (2 September 2014). «You’ve Got Luddites All Wrong». Vice. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Binfield, Kevin (2004). Luddites and Luddism. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Rude, George (2001). The Crowd in History: A Study of Popular Disturbances in France and England, 1730–1848. Serif.

- ^ a b Thomis, Malcolm (1970). The Luddites: Machine Breaking in Regency England. Shocken.

- ^ «Historical events – 1685–1782 | Historical Account of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (pp. 47–65)». British History Online. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Charles Wilson, England’s Apprenticeship, 1603–1763 (1965), pp. 344–45. PRO, SP 36/4/22.

- ^ Harrison, J. F. C. (1984). The Common People: A History from the Norman Conquest to the Present. London, Totowa, N.J: Croom Helm. pp. 249–53. ISBN 0709901259. OL 16568504M.

- ^ Beckett, John. «Luddites». The Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway. Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Roger Knight, Britain Against Napoleon (2013), pp 410–412.

- ^ Francois Crouzet, Britain Ascendant (1990) pp 277–279.

- ^ «The Luddites 1811–1816». victorianweb.org. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Dinwiddy, J.R. (1992). «Luddism and Politics in the Northern Counties». Radicalism and Reform in Britain, 1780–1850. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 371–401. ISBN 9781852850623.

- ^ Sale 1995, p. 188.

- ^ «Workmen discover secret chambers». BBC News. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Summer D. Leibensperger, «Brandreth, Jeremiah (1790–1817) and the Pentrich Rising.» The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (2009): 1–2.

- ^ Hobsbawm 1952, p. 58: «The 12,000 troops deployed against the Luddites greatly exceeded in size the army which Wellington took into the Peninsula in 1808.»

- ^ Sharp, Alan (4 May 2015). Grim Almanac of York. The History Press. ISBN 9780750964562.

- ^ Murder of William Horsfall – Newspaper report on the murder of William Horsfall

- ^ Huddersfield Exposed – William Horsfall (1770–1812).

- ^ «8th January 1813: The execution of George Mellor, William Thorpe & Thomas Smith». The Luddite Bicentenary – 1811–1817. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2020 – via ludditebicentenary.blogspot.com.

- ^ Lord Byron, Debate on the 1812 Framework Bill, Hansard, http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/1812/feb/27/frame-work-bill#S1V0021P0_18120227_HOL_7

- ^ Elizabeth Gaskell: The Life of Charlotte Bronte, Vol. 1, Ch. 6, for contemporaneous description of attack on Cartwright.

- ^ «Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1812» at books.google.com

- ^ «Lord Byron and the Luddites | The Socialist Party of Great Britain». worldsocialism.org. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ «Luddite Definition & Meaning | Dictionary.com».

- ^ Sale 1995, p. 205.

- ^ Jones 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (1 February 1997). «America’s New Luddites». Le Monde diplomatique. Archived from the original on 30 June 2002.

- ^ Jerome, Harry (1934). Mechanization in Industry, National Bureau of Economic Research. pp. 32–35.

- ^

Krugman, Paul (12 June 2013). «Sympathy for the Luddites». The New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2015. - ^ Ford 2009, Chpt 3, ‘The Luddite Fallacy’

- ^ Lord Skidelsky (12 June 2013). «Death to Machines?». Project Syndicate. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

Sources[edit]

- Ford, Martin R. (2009), The Lights in the Tunnel: Automation, Accelerating Technology and the Economy of the Future, Acculant Publishing, ISBN 978-1448659814. (e-book available free online.)

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, Gary M., and Robert D. Tollison. «Luddism as cartel enforcement.» Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft 142.4 (1986): 727–738. JSTOR 40750927.

- Archer, John E. (2000). «Chapter 4: Industrial Protest». Social unrest and popular protest in England, 1780–1840. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57656-7.

- Bailey, Brian J (1998). The Luddite Rebellion. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-1335-1.

- Darvall, F. Popular Disturbances and Public Order in Regency England (Oxford University Press, 1934)

- Dinwiddy, John. «Luddism and politics in the northern counties.» Social History 4.1 (1979): 33–63.

- Fox, Nicols (2003). Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite History in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-860-5.

- Grint, Keith & Woolgar, Steve (1997). «The Luddites: Diablo ex Machina«. The machine at work: technology, work, and organization. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-7456-0924-9.

- Haywood, Ian. «Unruly People: The Spectacular Riot.» in Bloody Romanticism (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2006) pp. 181–222.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (1952). «The Machine Breakers». Past & Present. 1 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1093/past/1.1.57.

- Horn, Jeff. «Machine-Breaking and the ‘Threat from Below’ in Great Britain and France during the Early Industrial Revolution.» in Crowd actions in Britain and France from the middle ages to the modern world (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2015) pp. 165–178.

- Jones, Steven E. (2006). Against technology: from the Luddites to Neo-Luddism. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-97868-2.

- Linebaugh, Peter. Ned Ludd & Queen Mab: machine-breaking, romanticism, and the several commons of 1811-12 (PM Press, 2012).

- Linton, David. «The Luddites: How did they get that bad reputation?» Labor History 33.4 (1992): 529–537. doi:10.1080/00236569200890281.

- McGaughey, Ewan (2018). «Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy». ssrn.com. SSRN 3044448.

- Munger, Frank. «Suppression of Popular Gatherings in England, 1800–1830». American Journal of Legal History 25 (1981): 111+.

- Navickas, Katrina. «The search for ‘general Ludd’: The mythology of Luddism.» Social History 30.3 (2005): 281–295.

- O’Rourke, Kevin Hjortshøj, Ahmed S. Rahman, and Alan M. Taylor. «Luddites, the industrial revolution, and the demographic transition.» Journal of Economic Growth 18.4 (2013): 373–409. JSTOR 42635331.

- Pallas, Stephen J. «‘The Hell that Bigots Frame’: Queen Mab, Luddism, and the Rhetoric of Working-Class Revolution». Journal for the Study of Radicalism 12.2 (2018): 55–80. doi:10.14321/jstudradi.12.2.0055. JSTOR 10.14321/jstudradi.12.2.0055.

- Patterson, A. Temple. «Luddism, Hampden Clubs, and Trade Unions in Leicestershire, 1816–17.» English Historical Review 63.247 (1948): 170–188. online

- Poitras, Geoffrey. «The Luddite trials: Radical suppression and the administration of criminal justice». Journal for the Study of Radicalism 14.1 (2020): 121–166.

- Pynchon, Thomas (28 October 1984). «Is It O.k. to Be a Luddite?». The New York Times.

- Randall, Adrian (2002). Before the Luddites: Custom, Community and Machinery in the English Woollen Industry, 1776–1809. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89334-3.

- Rude, George (2005). «Chapter 5, Luddism». The crowd in History, 1730–1848. Serif. ISBN 978-1-897959-47-3.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick (1995). Rebels against the future: the Luddites and their war on the Industrial Revolution: lessons for the computer age. Basic Books. ISBN 0-201-40718-3.

- Stöllinger, Roman. «The Luddite rebellion: Past and present». wiiw Monthly Report 11 (2018): 6–11.

- Thomis, Malcolm I. The Luddites: Machine-Breaking in Regency England (Archon Books. 1970).

- Thompson, E. P. (1968). The Making of the English Working Class.

- Wasserstrom, Jeffrey. «‘Civilization’ and Its Discontents: The Boxers and Luddites as Heroes and Villains.» Theory and Society (1987): 675–707. JSTOR 657679.

Primary sources[edit]

- Binfield, Kevin (2004). Writings of the Luddites. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-7612-5.

External links[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Luddite.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luddism.

Look up Luddite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Luddite Bicentenary – Comprehensive chronicle of the Luddite uprisings

- The Luddite Link – Comprehensive historical resources for the original West Yorkshire Luddites, University of Huddersfield

- Luddism and the Neo-Luddite Reaction by Martin Ryder, University of Colorado at Denver School of Education

- The Luddites and the Combination Acts from the Marxists Internet Archive

- The Luddites (1988)—Thames Television drama-documentary about the West Riding Luddites.

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ.

ЕГЭ. Мировая история. Кодификатор тем.

1066

Нормандское завоевание Англии

1095-1291

Крестовые походы

1204

Захват Константинополя крестоносцами

1215

Принятие Великой хартии вольности в Англии

1265

Возникновение Английского парламента

1302

Созыв Генеральных штатов во Франции

1337-1453

Столетняя война

1358

Жакерия во Франции

1381

Восстание под предводительством У. Тайлера в Англии

1389

Битва на Косовом поле

1419-1434

Гуситские войны

1445( середина 1440-х)

Изобретение книгопечатания И. Гуттенбергом

1455-1485

Война Алой и Белой розы в Англии

1461-1483

Правление Людовика XI во Франции

1453

Падение Византийской империи

1485-1509

Правление Генриха VII в Англии

1492

Открытие Америки Христофором Колумбом

1492

Завершение Реконкисты на Пиренейском полуострове

1498

Открытие Васко да Гамой морского пути в Индию

1517

Выступление М. Лютера с 95 тезисами, начало Реформации в Германии

1519-1521+

Кругосветное плавание экспедиции Ф. Магеллана

1521

Вормсский рейхстаг.Осуждение М. Лютера

1524-1525

Крестьянская война в Германии

1534

Начало Реформации в Англии

1555

Аугсбургский религиозный мир

1562-1598

Религиозные войны во Франции

1566-1609

Освободительная война в Нидерландах

1569

Образование Речи Посполитой

1572

Варфоломеевская ночь во Франции

1579

Утрехтская уния

1588

Разгром Англией Непобедимой армады

1598

Нантский эдикт Генриха IV во Франции

1618-1648

Тридцатилетняя война

1585-1642

(с 1624-1-ый министр )

Деятельность кардинала Ришелье на посту первого министра Франции

1640 ( до 1660)

Начало деятельности Долгого парламента в Англии, начало Английской буржуазной революции

1641

Принятие английским парламентом «Великой ремонстрации»

1642-1652

Гражданская война в Англии

1643-1715

Правление французского короля Людовика XIV

1648

Вестфальский мир

1649

Казнь английского короля Карла I

1649 ( до 1660)

Провозглашение Англии республикой

1653 ( до 1659)

Протекторат О. Кромвеля

1660

Реставрация династии Стюартов в Англии (восстановление на престоле династии Стюартов, свергнутых в 1649г)

1688

«Славная революция» в Англии( свергнут король Яков 2 Стюарт, взошёл на трон Вильгельм 3)

1643-1715

Правление Людовика XIV во Франции

1715-1774

Правление Людовика XV во Франции

1740-1786

Правление Фридриха II в Пруссии

Начало 19 века

Движение луддитов в Англии (выступали против внедрения машин в производство)

16 декабря 1773

«Бостонское чаепитие» — акция протеста американских колонистов в ответ на действия британского правительства, в результате которого в Бостонской гавани был уничтожен груз чая. Это событие стало началом Американской революции.

4 июля 1776

Принятие «Декларации независимости» США

1787

Принятие конституции США

1789

Начало революции во Франции ( 14 июля 1789- штурм Бастилии)

1789

Принятие Декларации прав человека и гражданина

1791

Принятие Билля о правах в США

1789 — 1797

Президентство Дж. Вашингтона в США — первого Президента США

20 апреля 1792 (по 17 ноября 1799)

Начало революционных войн Франции

1792

Крушение монархии во Франции

1793( по 1794)

Приход к власти во Франции якобинцев

1793

Казнь короля Людовика XVI во Франции

1796-1797

Итальянский поход Наполеона Бонапарта

1798-1801

Египетский поход Наполеона Бонапарта

9 ноября 1799

Государственный переворот Наполеона Бонапарта 18–19 брюмера

1804

Провозглашение Наполеона императором Франции

Ноябрь 1799- июнь 1815

Наполеоновские войны

1814

Свержение Наполеона

1 (20)марта 1815 – 7 (22 )июля 1815

«Сто дней» Наполеона

1823, 2 декабря

Провозглашение доктрины Монро в США («Америка для американцев»)

1830

Революция во Франции

1836-1848

Чартистское движение в Англии

1848-1849

«Весна народов»: революции в европейских странах

1861-1865

Гражданская война в США

1870

Объединение Италии

1862-1890

Деятельность Бисмарка во главе Пруссии и Германии

1870-1871

1871

Франко-прусская война

Провозглашение Германской империи

1868

Революция Мэйдзи в Японии

1879-1882

Создание Тройственного союза (Германия, Австро-Венгрия и Италия)

1904-1907

Создание Антанты (Россия, Англия и Франция)

1912-1913

Балканские войны

28 июня 1914

«Сараевский инцидент», убийство наследника австрийского престола эрцгерцога Франца Фердинанда

28 июня 1914 – 11 ноября 1918

Первая мировая война

1918

Революция в Германии

1919-1921

Парижская мирная конференция

1919

Учреждение Лиги Наций

1921-1922

Вашингтонская конференция (об ограничении морских вооружений и проблемах Дальнего Востока и бассейна Тихого океана)

1922

Приход фашистов к власти в Италии

1929-1932

Мировой экономический кризис, «великая депрессия»

1933

Приход Гитлера к власти в Германии

1933

«Новый курс» Ф. Рузвельта в США (цель: вывести страну из кризиса 1929-1933)

Июль 1936-апрель 1939

Фашистский мятеж и гражданская война в Испании

1936

Антикоминтерновский пакт Германии и Японии

1938

Захват Австрии нацистской Германией (аншлюс)

1938

Подписание Мюнхенского соглашения

1 сентября 1939-2 сентября 1945

Вторая мировая война

1941, 7 декабря

Японская атака на Пёрл-Харбор и вступление США в войну

1944, 6 июня

Высадка англо-американских войск в Нормандии. Открытие Второго фронта

1945, 8 и 9 августа

Атомная бомбардировка США Хиросимы и Нагасаки

2 сентября 1945

Капитуляция Японии. Окончание Второй мировой войны

1945-1946

Нюрнбергский процесс над нацистскими преступниками

1949

Образование HATО

1949

Провозглашение Китайской Народной Республики

1959

Победа революции на Кубе

1965-1973

Война США во Вьетнаме

1966

«Культурная революция» в Китае

1989-1991

«Бархатные» революции в странах Центральной и Восточной Европы

1990

Объединение ГДР и ФРГ

Жизнь рабочих на фабриках была очень тяжёлой. Многие из них искали утешения в религии. Большой популярностью стало пользоваться новое движение в протестантизме — методизм. Джон Уэсли, основатель методизма, считал, что путь к богу лежит через свободу воли и строгое методичное соблюдение церковных обрядов. Он и его сторонники много проповедовали за пределами церквей, что было запрещено англиканской церковью. Популярным местом для проповедей стали фабрики и районы проживания рабочих. Методисты много внимания уделяли благотворительности, они основывали больницы и столовые для рабочих, старались улучшить их жизнь.

Рис. (1). Проповедь Джона Уэсли

Однако недовольство рабочих было столь велико, что выливалось в открытые протесты. В (1811) г. сформировалось движение луддитов. Это были рабочие, которые выступали против технического прогресса. Они видели «корень зла» в машинах, которые заменили рабочих и стали причиной безработицы и низких зарплат. Сначала они подавали петиции в парламент с требованиями запретить применение машин. Это не принесло результатов, поэтому они перешли к прямым действиям — стали ломать станки на фабриках, громить их и устраивать поджоги.

Движение луддитов получило название по имени рабочего Неда Лудда. По легенде он ещё в (1779) г. разбил два станка для вязания чулок. Однако историки не нашли никаких подтверждений, что такой человек существовал.

Рис. (2). Предводитель луддитов

Выступления луддитов были массовыми в (1810)-х гг. Они устраивали забастовки, ломали станки, поджигали фабрики, иногда устраивали потасовки и даже убивали владельцев фабрик. Парламент отреагировал на это ужесточением законов. С (1812) г. вывод из строя машин карался смертной казнью. Самым большим выступлением было Пинтричское восстание (1817) г. Несколько сотен человек с оружием направились в сторону Лондона. Для подавления восстания были применены силы армии. Множество луддитов были казнены, заключены в тюрьмы или высланы в Австралию.

Рис. (3). Луддиты, ломающие станки

Конституционный конвент в Филадельфии, подписание Конституции

Даты по зарубежной истории, представленные в кодификаторе ЕГЭ по истории за 2018 год, с краткими пояснениями.

| Событие | Дата |

|---|---|

| Правление Людовика XV во Франции – одно из самых длительных правлений в истории, участник Семилетней войны. Современник: мадам дэ Помпадур. | 1715-1774 |

| Правление Фридриха II в Пруссии – представитель просвещенного абсолютизма, участник Семилетней войны | 1740-1786 |

| «Бостонское чаепитие» – протест американских колонистов против британского правительства. Была уничтожена партия чая, принадлежавшая Ост-Индской кампании. | 16 декабря 1773 |

| Принятие Декларации независимости США – британские колонии в Северной Америки объявили о своей независимости от Великобритании | 4 июля 1776 |

| Принятие конституции США – первая в истории конституция. Утверждала разделение властей. | 17.09 1787 |

| Начало революции во Франции – ключевое событие – Взятие Бастилии, главной крепости-тюрьмы Франции. Персоналии: Людовик XVI (впоследствии казнённый), Робеспьер, Мария-Антуанетта | 1789 |

| Принятие Декларации прав человека и гражданина – ключевой документ Великой Французской революции | 1789 |

| Принятие Билля о правах в США – первые 10 поправок к Конституции США(свобода религии, слова, прессы, собраний, право на оружие). | 1789-1791 |

| Президентство Дж. Вашингтона в США – первый всенародно избранный президент США | 1789-1797 |

| Крушение монархии во Франции – штурм Тюильри (парижского дворца французских королей) | 1792 |

| Приход к власти во Франции якобинцев – радикальная революционная партия. Представители – Марат, Дальтон, Робеспьер | 1793 |

| Казнь короля Людовика XVI во Франции и его супруги Марии Антуанетты | 1793 |

| Итальянский (битва при Риволи – разгром революционным движением европейской коалиции) и Египетский (попытка завоевания Египта и конкуренции с Англией в вопросах колоний) походы Наполеона Бонапарта | 1796-1797, 1798-1801 |

| Переворот 18 брюмера – государственный переворот, в результате которого во Франции к власти приходит Наполеон. Брюмер – осенний месяц в республиканском календаре | 9 ноября 1799 |

| Провозглашение Наполеона императором Франции – первого «пожизненного» консула провозглашают императором | 1804 |

| Наполеоновские войны – войны с Россией, Австрией, Англией | 1800-1815 |

| «Сто дней» Наполеона – бегство Наполеона с острова Эльба, последняя битва при Ватерлоо и ссылка бывшего императора на остров Святой Елены | 1 марта-7 июня 1815 |

| Движение луддитов в Англии – «луддиты» – общественное движение против промышленной революции (внедрения машин в производство), которая лишала работы большое количество людей. | 1811-1813 |

| Провозглашение доктрины Монро в США – принцип взаимного невмешательства стран Американского и Европейского континентов во внутренние дела друг друга | 2 декабря 1823 |

| Революция во Франции – «три славных дня», свержение Карла Х, и возведение на престол короля Филиппа I. | 1830 |

| Чартистское движение в Англии – социальное движение в Англии, вызванное ростом безработицы | 1836-1848 |

| «Весна народов» – революции в европейских странах. Австрия, Венгрия, Чехия, Хорватия | 1848-1849 |

| Гражданская война в США – война между союзом рабовладельческих штатов (Конфедерацией) на юге и нерабовладельческих штатов на севере. Персоналии: Авраам Линкольн, Джефферсон Девис | 1861-1865 |

| Объединение Италии – рисорджименто или воссоединение, преодоление раздробленности Италии | сентябрь 1870 |

| Революция Мэйдзи в Японии – комплекс реформ, благодаря которым Япония из аграрной отсталой страны становится индустриальной | 1868 |

| Франко-прусская война – участники Бисмарк и Наполеон III. Итог: разгром Франции и повод к провозглашению Германской империи в 1871. | 1870-1871 |

| Создание Тройственного союза – Германия, Австро-Венгрия, Италия. Будущие участники Первой мировой войны. | 1879-1882 |

| Cоздание Антанты (с фр. «Сердечное согласие») – Россия, Англия, Франция. Будущие участники Первой мировой войны. | 1891-1907 |

Записаться на курсы ЕГЭ по истории в Красноярске вы можете позвонив по телефону +7(391)2-950-216, +7(391)2-4141-23

Глушенкова Ольга Александровна,

преподаватель истории и обществознания

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.