Законодательство США в части регулирования деятельности адвокатуры значительно отличается от аналогичных норм стран континентальной системы права, что делает его весьма привлекательным для исследования.

При этом сразу следует уточнить, что в американском праве отсутствует привычный российским юристам термин «адвокат». Вместо него американские коллеги используют термин «юрист, имеющий право заниматься юридической практикой» («practice of law»). Для того чтобы стать практикующим юристом в США и иметь возможность представлять интересы клиента в суде необходимо состоять в сообществе юристов («bar», в дальнейшем в настоящей статье вместо американского термина «bar» мы будем использовать термин «Ассоциация юристов»). При этом, в отличие от Российской Федерации, где требования к получению статуса адвоката устанавливаются на федеральном уровне, каждый штат США и аналогичная юрисдикция (например, территории под федеральным контролем) имеет свою собственную судебную систему и устанавливает свои собственные правила приема в ассоциацию юристов штата.

Используемый в американском праве термин «bar» (American Bar Association, State bar of Illinois и т.д.) в дословном переводе означает «перила». В начале 16-го века перила разделяли зал в английском Иннс-Корт на 2 части — в одной находились преподаватели, а в другой части находились ученики и слушатели. Студенты, которые успешно проходили обучение и официально становились адвокатами, «призывались в сообщество [юристов]», пересекая символический физический барьер («bar») и, таким образом, становились «допущенными в сообщество [юристов]». Позже этот термин означал деревянные перила, отделяющие место судьи в зале заседании от места, где находились обвиняемые вместе со своим адвокатом. Первый юридический квалификационный экзамен на территории Соединенных Штатов, был установлен колонией Делавэр в 1763 году в форме устного экзамена, который принимал действующий судья. К концу 19-го века экзамены принимались уже комиссией адвокатов, причем в письменной форме.

Как мы указали ранее, каждый штат имеет свои собственные правила приема в Ассоциацию юристов, которые должны быть соблюдены юристом, желающим заниматься юридической практикой. Проанализировав требования различных штатов к кандидатам, мы приходим к выводу, что для получения статуса адвоката в США кандидату необходимо получить юридическое образование, успешно пройти экзамен на проверку личностных качеств, сдать квалификационный экзамен и оплатить членский взнос. Рассмотрим каждое указанные требования более подробно.

По общему для большинства штатов правилу кандидат на получение статуса адвоката должен иметь как минимум степень бакалавра юриспруденции (Juris Doctor), полученную в аккредитованном Американской ассоциацией юристов (American Bar Association) учебном заведении.

В таких штатах как Калифорния и Джорджия правила получения статуса требуют прохождения обучения в учебных заведениях, утвержденных государственными органами, но при этом не аккредитованных Американской ассоциацией юристов. В штате Нью-Йорк особое внимание уделяется лицам, получившим зарубежное юридическое образование, причем большинство обладателей степени бакалавра юриспруденции имеют право сдавать экзамен в баре и, после успешного прохождения, получить статус адвоката.

Иной подход к оценке полученного кандидатом применяется в штате Аризона, где к квалификационному экзамену не допускаются лица, получившие юридическое образование учебных заведениях, не аккредитованных Американской ассоциацией юристов. Законность такого правила неоднократно была предметом рассмотрения в судах Аризоны, однако суд всегда поддерживал доводы Ассоциации юристов Аризоны. Иными словами, выпускники учебных заведений, не аккредитованных в Американской ассоциации юристов, не могут получить статус адвоката в штате Аризона, однако это не является препятствием к получению статуса в других штатах.

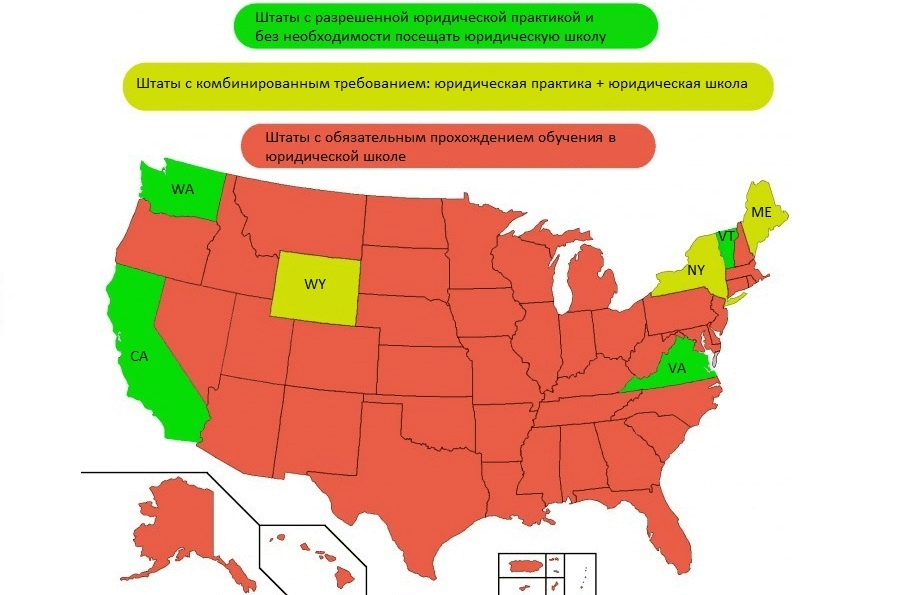

Особенностью американского законодательства в части требований к кандидатам на получение статуса адвоката является возможность приобретения такого статуса без получения юридического образования. Для этого претендент должен (если это разрешено нормами конкретного штата) успешно пройти программу «Чтение закона» («Reading the law»). Дополнительные требования предъявляются в штате Нью-Йорк, согласно которым заявители, прошедшие программу «Чтение закона», должны также не менее одного года обучаться в юридической школе.

Во всех штатах США претенденты на получение статуса адвоката проходят многоступенчатую профессиональную экспертизу (Multistate Professional Responsibility Examinatio (MPRE) — экзамен, проверяющий знание правил профессиональной ответственности адвокатов. Этот тест не содержит каких-либо вопросов, касающихся квалификации юриста, и не проводится одновременно с квалификационным экзаменом. Большинство кандидатов к моменту окончания обучения уже сдали такой экзамен, как правило он сдается сразу после изучения предмета «Профессиональная ответственность юриста» (необходимый курс во всех аккредитованных Американской ассоциацией юристов учебных заведениях).

Следующим необходимым для получения статуса адвоката этапом является сдача квалификационного экзамена, который проводится Ассоциацией юристов или Верховным судом конкретного штата. В большинстве штатов проводится унифицированный квалификационный экзамен (Uniform Bar Examination (UBE) с целью «проверки знаний и навыков, которые каждый адвокат должен продемонстрировать до того, как он будет признан практикующим юристом», и для «единообразного подхода к предъявляемым требованиям к квалификации практикующих юристов». В штатах, где проводится UBE разрешено дополнительно проверять знания кандидатов по федеральному законодательству посредством теста. Унифицированный экзамен состоит из трех частей:

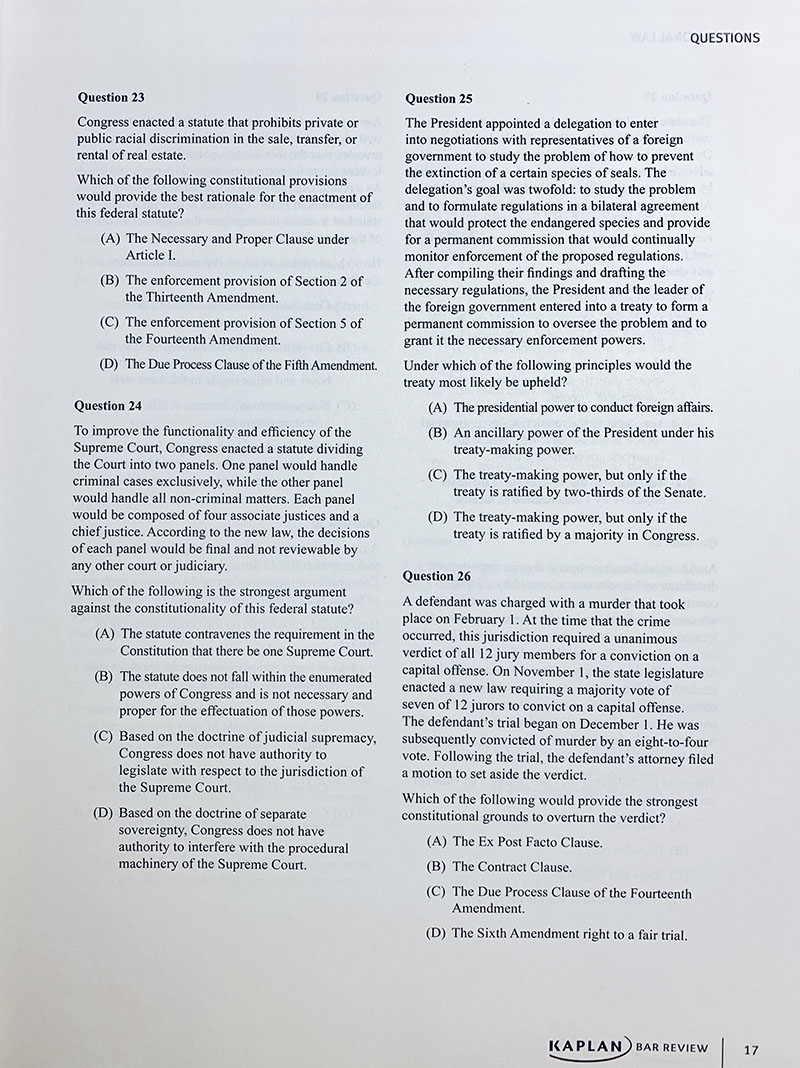

Экзамен (Multistate Bar Examination, MBE), стандартизированный тест, состоящий из 200 вопросов с множественным выбором, охватывающих ключевые области права: конституционное право, обязательственное право, уголовное право и процесс, федеральные правила гражданского судопроизводства, Федеральные правила доказывания и Земельное право. У претендента на получение статуса есть три часа, чтобы ответить на 100 вопросов на утренней сессии и столько же времени для ответа на вопросы дневной сессии (экзамен сдается в феврале и июле);

- Эссе (MultistateEssayExamination, MEE) — унифицированный, хотя и не стандартизованный тест, который анализирует способность кандидата анализировать правовые вопросы и эффективно передавать их в письменной форме. Темы варьируются от выше упомянутых тем и включают вопросы в таких областях как корпоративное право, коммерческое право, наследование и семейное право (экзамен также сдается в феврале и июле);

- Тест на производительность (MultistatePerformanceTest, MPT) — тест, в котором каждый кандидат должен выполнить стандартную для юриста задачу (например, составить заявление или письмо). Кандидату предоставляются материала дела и «библиотека», в которой содержатся необходимые материалы судебной практики плюс некоторые несоответствующие материалы.

В тех штатах, которые не принимают унифицированный квалификационный экзамен, кандидаты должны пройти квалификационный экзамен, а также экзамен на профессиональную ответственность («этика»), включенный в качестве части основного экзамена.

В дополнение к требованиям к необходимому образованию и сдаче экзаменов, большинство штатов требуют от заявителя продемонстрировать высокие морально-этические качества. Комитеты по персоналу Ассоциаций юристов штатов обращаются к истории заявителя, чтобы определить, будет ли человек вести себя достойным образом и в будущем. Для этого комиссия принимает во внимание наличие уголовные аресты или обвинительные приговоры, нарушения кодекса академической чести, предшествующие банкротства или доказательства финансовой безответственности, наличия психических расстройств, совершение преступлений или проступков сексуального проступка, предшествующие гражданские иски и даже историю вождения. Например, в начале 2009 года лицу, принятому в Ассоциацию юристов Нью-Йорка и имевшему задолженность более 400 000 долларов, было отказано в приеме на работу в Апелляционный отдел Верховного суда штата Нью-Йорк из-за чрезмерной задолженности. Позднее лицо было исключено из реестра адвокатов штата Нью-Йорк.

При подаче заявки на участие в адвокатской проверке штата заявители должны заполнить множество анкет, требующих раскрытия важной личной, финансовой и профессиональной информации. Например, в штате Вирджиния каждый заявитель должен заполнить 24-страничный вопросник и может быть вызван в комитет Ассоциации юристов штата для уточнения информации. При заполнении анкет и на всех этапах процесса получения статуса адвоката честность имеет первостепенное значение. Заявитель, который не раскрывает существенные факты, независимо от того, ложными или неточными являются предоставляемые им сведения, ставит под угрозу свои шансы попадания в реестр адвокатов.

После сдачи всех необходимых экзаменов и в случае соблюдения всех рассмотренных выше требований для получения статуса адвоката кандидату остается пройти процедуру присяги. Механика этой процедуры широко варьируется в зависимости от штата, но в целом суть сводится к присяге кандидата соблюдать закон и последующем включении кандидата в реестр практикующих юристов.

Например, в штате Калифорния, кандидат дает клятву перед любым государственным судьей или нотариусом, который затем подписывает специальную форму, которая передается в Ассоциацию юристов штата. Получив подписанную форму, Ассоциация юристов Калифорнии добавляет успешных кандидатов в список претендентов, рекомендованных для приема в адвокатуру, который автоматически ратифицируется Верховным судом Калифорнии на следующем очередном еженедельном заседании; затем кандидат включается в официальный реестр адвокатов.

После внесения юриста в реестр адвокатов он может практиковать право в пределах того штата, в Ассоциации юристов которого он состоит, поэтому большинство адвокатов получают возможность практиковать права только в одном штате. Тем не менее, законодательство различных штатов прямо не запрещает получение возможности вести свою деятельность на территории нескольких штатов — либо с помощью сдачи экзаменов в других штатах, либо после прохождения процедуры признания статуса в другом штате. Это характерно для тех, кто живет и работают в мегаполисах, которые разрастаются на несколько штатов (Вашингтон, Нью-Йорк, Чикаго). Адвокаты, ведущие свою деятельность около границ штата, часто стремятся попасть в реестры нескольких штатов, чтобы расширить свою клиентскую базу.

Однако необходимо учитывать, что даже при подтверждении статуса адвоката в другом штате, возможность ведения практики одновременно в нескольких штатах видится весьма призрачной. Например, юристы, имеющие право практиковать в Вирджинии, должны предъявить доказательства намерения практиковать полный рабочий день в штате Вирджиния и им запрещается поддерживать офис в любом другом штате. Кроме того, юристы исключаются из реестра адвокатов, если они больше не поддерживают офис в пределах одного штата.

БЫРЛЭДЯНУ Денис Викторович

аспирант кафедры конституционного и муниципального права Среднерусского института управления — филиала Российской академии народного хозяйства и государственной службы при Президенте Российской Федерации, г. Орёл

Профессия юриста является одной из самых престижных и востребованных в США, в стране, где о правах человека говорят чаще, чем в любом другом государстве мира. Это – сложная наука для самих американцев, требующая максимум усилий и высокой конкурентоспособности. Что же в таком случае делать юристу с иностранным дипломом, мечтающим стать частью правовой системы Америки?

Для юриста с иностранным образованием, желающим сделать карьеру по специальности в США, в первую очередь должен задаться вопросом: в каком штате я хочу жить и вести практику юриста? Независимо оттого, иностранец он или американец, у юриста будет лицензия на юридическую деятельность только в том штате, где он сдал экзамен (Bar exam, как его называют).

К сожалению, прохождение этого экзамена может обернуться для юриста, получившего образование за границей, очень сложной задачей. Образование, полученное в юридической школе США (1 год для специалиста с признанным иностранным дипломом), требуется в большинстве штатов страны. Но не во всех. Нью-Йорк, Калифорния и Вирджиния в числе тех штатов, где единственное, что требуется от юриста, это прохождение экзамена без учебы в местной юридической школе.

В любом случае, специалисты, получившие образование за рубежом, должны иметь диплом, проверенный Американской ассоциацией юристов. Сама проверка знаний занимает довольно много времени – год и больше. Но если диплом принят, то юрист-иностранец может приступать к подготовке к экзамену на получение лицензии.

Bar examination. Что представляет собой экзамен на получение юридической лицензии

Экзамен традиционно проводится два раз в год: в феврале и июле. Он занимает 2-3 дня в зависимости от выбранной им юрисдикции и штата. Один из дней отводится на проверку знаний по общему федеральному законодательству, касающегося не уникальных для каждого штата положений. В другой день вниманию экзаменуемых представляется тест по законам, работающих на территории того штата, в котором экзаменуемый планирует вести юридическую практику. В перечень испытаний входят:

- тест множественного выбора;

- тест с вопросами-ситуациями;

- тест, требующий развернутых ответов.

В некоторых штатах может быть предложено пройти устный экзамен перед специальной комиссией.

Примерно 30% экзаменуемых составляют именно иностранные специалисты. Стоит отметить, что к сторонней помощи в подготовке к этому экзамену (курсы, репетиторы) часто прибегают даже сами американцы, что уж говорить об иностранцах, планирующих успешно сдать экзамен с первого раза.

Что стоит учесть перед переездом в США?

Прежде чем начать новую жизнь иностранному юристу предстоит обдумать ряд вопросов. Очень важно понимать, какой именно штат отвечает тем экономическим и бизнес-запросам, которые будут важны в его практике. Ведь у каждого из 50 штатов (+ округ Колумбия) есть своя специфика, учитывая которую легче сделать карьеру. Кроме того, будущему американскому юристу необходимо определиться с тем, какая инфраструктура, какое окружение и возможности города/штата подходят ему лично и его семье.

Выбор юрисдикции также занимает одно из центральных мест в приоритетах при планировании переезда в Америку. Ведь от нее напрямую может зависеть образ жизни, который планирует вести будущий юрист США.

При всем многообразии компаний, готовых помочь иностранному юристу в Америке, ему стоит понимать, что придется очень серьезно потрудиться, чтобы реализовать свою американскую мечту.

Подготовка и экзамен на статус адвоката в США

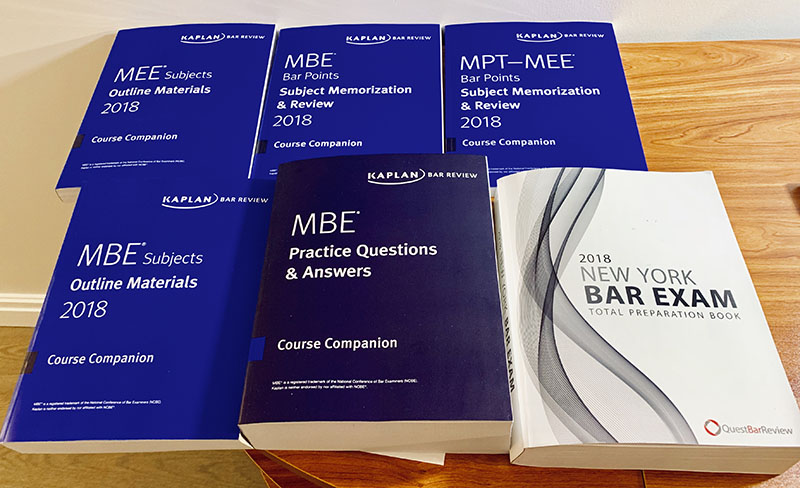

Адвокатура основная часть правовой культуры любой страны. Интересен сравнительный анализ с Россией. В США подготовкой занимаются две фирмы конкурента – BARBRI Bar exam Tutoring и KAPLAN Barexam.

Цена подготовительных двух месячных курсов 2500 долларов, это онлайн программа и живая система лекционной подготовки с приложением огромного объёма учебной литературы.

Когда я написал учебное пособие для будущих российских адвокатов на 1300 страниц, выдержавшее 5 изданий, думал это много, но по сравнению с США? Основной учебник аналогичен нашему, вопрос и ответ, но в США это система тест-вопроса и намеренно обманчивых нескольких ответов, без глубокого знания обязательно промахнёшься. Вопросы практически-прикладного характера, где основа не просто знание нормативной базы, а ее применение на скорости.

В Калифорнии, Вашингтоне ДС, и Нью-Йорке можно быть допущенным к bar-экзамену, имея иностранное юридическое образование или практикующему иностранному адвокату. Необходимо предоставить диплом, удостоверение, заполнить анкету, сдать отпечатки пальцев, сообщить о всех совершенных правонарушениях (даже о ДТП), представить перечень всех долгов, пройти собеседование с комиссией и экзамен, он платный — 700 долларов.

Экзамен продолжается два дня. Первый – предоставляется файл с материалами дела и актами законодательства, которые нужно подготовить меморандум, ответ адвокату оппонента, т.п. За 3 часа кандидат должен, проанализировать, разработать стратегию написать эссе из нескольких сфер права.

Следующий день — тесты по 8 «ключевым» сферам права (200 вопросов-ситуаций с предполагаемыми ответами, на вопрос 1,8 минуты) 6 часов с перерывом. Результаты экзамена публикуются в открытой печати,с последующей выдачей соответствующей лицензии после присяги.

Экзамены похожи на участие в конкурсе — у каждого участника свой браслет-номер. Экзаменаторы не знают, кто идет под этим номером, сын президента или простой гражданин.Сумки проносить в аудиторию, где проходит экзамен запрещено. Разрешается взять с собой лишь маленький прозрачный пакетик с самым необходимым: ручками, карандашами. Можно бутерброд и беруши, что бы не отвлекаться.

На сегодняшний день в США более 1,000,000 адвокатов, в России более 75 тыс. адвокатов. Около 40,000 новых адвокатов сдают bar examination в США каждый год.

В Штате Нью-Йорк– 15 юридических школ (Albany, Brooklyn, Cardozo, Columbia, Cornell, Fordham, Hofstra, New York Law School, NYU, Pace, St. John’s, Syracuse, Touro (Fuchsberg), SUNY Buffalo CUNY Queens College).

Download Article

Download Article

If you want to be a lawyer, you have to pass the Bar exam in the state where you want to practice – and usually, that means you have to graduate from law school first. California is one of only a handful of states that allows people to take the bar exam without going to law school. However, you should keep in mind that your odds of actually passing are extremely low. In law school, you learn to think like a lawyer and you use that critical thinking to help increase your likelihood of passing the bar exam. The California Bar exam has a passage rate of less than 50 percent, and that rate shrinks to less than 5 percent among exam takers who didn’t graduate from law school.[1]

Even if you are fortunate enough to pass the bar exam without a law degree, it is nearly impossible to be hired from any law firm without graduating from an ABA-accredited law school.

-

1

Complete the required pre-legal education. Before you start studying law, you must finish at least two years of college work, or take the CLEP (College Level Equivalency Program) test.[2]

- Two years equates to at least 60 semester hours or 90 quarter hours of credit.

- You must have a grade average high enough to qualify for a degree, had you completed the full four years.[3]

-

2

Find an attorney or judge to supervise you as your mentor. It’s up to you to find someone willing to mentor you for the next four years without receiving any pay or even continuing education credit.

- The attorney or judge you choose must be admitted to the active practice of law in California, and have been in good standing for at least five years.

- You will not be working for your mentor. Rather, you will be following a course of study proposed by the attorney or judge, who will personally supervise you at least five hours a week.[4]

- Try to study law under an attorney who practices the same type of law you want to practice after you pass the bar exam.[5]

- Your mentor also must examine you at least once a month on the material you studied that month.

- Once every six months, your mentor will report to the Committee of Bar Examiners the hours you studied each week and the subjects and materials you studied.[6]

Advertisement

-

3

Register as a law student. Before you submit any other forms, you must apply with the State Bar of California Office of Admissions to register as a law student.[7]

Your application for registration must include a $113 fee.[8]

-

4

Submit a Notice of Intent to Study in a Law Office or Judge’s Chambers. Within 30 days[9]

of the day you start your study program, you must submit the state’s form along with a $150 fee.[10]

-

5

Plan your program of study. Since you have to pass the Bar exam before you can start practicing law, your study should focus primarily on Bar subjects.

- Subjects tested on the California Bar include business associations, civil procedure, community property, constitutional law, contracts, criminal law and procedure, evidence, real property, torts, and wills and trusts.[11]

- You must study at least 18 hours a week for 48 weeks to acquire credit for one year of legal study. You must have at least four years of legal study at a law office or judge’s chambers before you can take the California Bar exam.[12]

- To qualify, your study hours must happen in the law office or the judge’s chambers during regular business hours.[13]

- Within 30 days of the day you begin your study, your mentor must send the Committee of Bar Examiners an outline of your course of study. The Committee doesn’t critique this outline or oversee any of your work while you study.[14]

- Subjects tested on the California Bar include business associations, civil procedure, community property, constitutional law, contracts, criminal law and procedure, evidence, real property, torts, and wills and trusts.[11]

-

6

Submit semi-annual reports. Within 30 days of the conclusion of a six-month period of study, you and your mentor must send a report of your studies for that time accompanied by a $100 fee.

- The report may include the hours you studied, the areas of law you covered and course materials you used, cases you read, exercises you completed, and evaluation of your performance on monthly exams.[15]

- The report may include the hours you studied, the areas of law you covered and course materials you used, cases you read, exercises you completed, and evaluation of your performance on monthly exams.[15]

Advertisement

-

1

Study for the First-Year Law Students’ Examination (FYLSX). After you’ve completed one year of legal education, you must take and pass the FYLSX, also known as the «Baby Bar.»[16]

- The FYLSX takes one day. During the morning session you have approximately four hours to answer four essay questions. After a lunch break, the test day concludes with a three-hour afternoon session during which you’ll answer 100 multiple-choice questions.[17]

- Since the exam covers contracts, criminal law, and torts, these subjects should be the focus of your first year of study.[18]

- Study aids and sample essay exam questions with answers are available from the Office of Admissions of the California Bar.

- The FYLSX takes one day. During the morning session you have approximately four hours to answer four essay questions. After a lunch break, the test day concludes with a three-hour afternoon session during which you’ll answer 100 multiple-choice questions.[17]

-

2

Apply to take the FYLSX. The exam is offered in June and October each year, and must be taken either in Los Angeles or San Francisco.[19]

- Your application must be accompanied by a fee of $566.[20]

- If you file your application after the regular deadline passes, expect to pay additional late filing fees which can be as much as $200.[21]

- After you apply, your mentor will be sent a certification form to prove you’ve completed a year of law study. You have until the final eligibility deadline to submit your certification.[22]

- Your application must be accompanied by a fee of $566.[20]

-

3

Take the FYLSX. A passing score on the exam is a total score of 560 or higher.

- Your multiple-choice score consists of the number of questions you answered correctly, converted to a 400-point scale that adjusts for variations in difficulty across the different versions of the test.

- Your total raw essay score ranges between 160 and 400 points. This score is converted to the same 400-point scale used for the multiple-choice questions.

- Your converted essay scores and converted multiple-choice scores are added together to produce your total score.[23]

- If you don’t pass the Baby Bar on the first try, you can try again. The California Bar gives you a total of three chances to pass the exam. If it takes you more than three attempts, you only get credit for a single year of legal education – which means you wouldn’t get credit for any time you spent studying while you were retaking the FYLSX.[24]

Advertisement

-

1

Gather materials necessary to complete your application. The Committee conducts a thorough and intense background examination before determining you have sufficient moral character to practice law in California.

- For example, to complete the application you will need to list employment history going back to your 18th birthday. You may not recall the addresses of places you worked part-time, or the names of your supervisors. You’ll need to track down this information.

- Read the entire application through once before you answer any questions, and make notes of information you need. Then find that information before you sit down to fill out the application.[25]

-

2

Have a set of fingerprints made. If you live in California, you must submit fingerprints using California Live Scan Technology. If you live outside the state you can submit a fingerprint card along with a request for exemption.[26]

-

3

Complete your application. You must answer all questions on the application completely and correctly or your application will be considered incomplete and won’t be reviewed.[27]

-

4

Submit your application. If you have completed the application online, you must mail a hard copy to the Office of Admissions in Los Angeles within 30 days of submitting it online.[28]

- Use the checklist that prints with your application to double-check and ensure that all the forms and pages have been completed, and that you’ve signed all the forms that require your signature.[29]

- Your application will be considered abandoned if it isn’t complete within 60 days of filing.[30]

- You can file your application at any time after you begin your law study,[31]

but the Committee recommends you file at least eight to ten months prior to the date you anticipate being admitted to practice law in California.[32]

- Your application must be accompanied by a filing fee of $525.[33]

- The Committee will send confidential reference questionnaires to any references, employers, or law schools that are listed on your application.

- Use the checklist that prints with your application to double-check and ensure that all the forms and pages have been completed, and that you’ve signed all the forms that require your signature.[29]

-

5

Wait for a determination on your application. It takes at least 180 days for the Committee to complete the background check, finish processing an application, and make a decision.[34]

- You will receive a notice from the Committee within 180 days. Either the notice will tell you the determination is positive, or it will tell you that the Committee requires further information from you, a government agency, or another source. If the Committee requests additional information from you, you should submit it promptly.[35]

- If the Committee still has questions about or issues with your application, you may receive an invitation to an informal hearing. You don’t have to attend, and it won’t affect the Committee’s decision if you decide not to go.[36]

However, attending the hearing could allow you to clear up problems that are keeping you from getting a positive determination.

- You will receive a notice from the Committee within 180 days. Either the notice will tell you the determination is positive, or it will tell you that the Committee requires further information from you, a government agency, or another source. If the Committee requests additional information from you, you should submit it promptly.[35]

-

6

Update your application as necessary until you are admitted to the Bar. Until you pass the Bar exam, you are responsible for amending your application when any of the information you provided changes, or you have new information that should be added. Failure to do so within 30 days of your knowledge of the change may result in the suspension of a positive determination.[37]

- To submit amendments, you can either print your application and mark the places where changes need to be made, or send in a separate sheet of paper on which you’ve written the changes or additions down and signed it.[38]

- Amendments may be submitted with your hard copy application or mailed separately to the Los Angeles Office of Admissions.[39]

- To submit amendments, you can either print your application and mark the places where changes need to be made, or send in a separate sheet of paper on which you’ve written the changes or additions down and signed it.[38]

-

7

File for an extension. A positive moral character determination is valid for 36 months.[40]

If you haven’t passed the Bar in that time, you can submit an application for an extension along with a fee of $252.[41]

Advertisement

-

1

Study for the MPRE. The MPRE is administered and graded by the National Conference of Bar Examiners,[42]

and tests your understanding of the American Bar Association Model Rules of Professional Conduct, the ABA Model Rules of Judicial Conduct, and other court decisions or rules of procedure and evidence that deal with attorney ethics and professional conduct.[43]

- The test consists of 60 multiple-choice questions, only 10 of which are scored. You will have two hours to complete the test. Each question presents a hypothetical set of facts followed by a question. You must pick the best possible answer to the question from the four options presented.[44]

- In addition to reading the ABA Model Rules, you can study for the MPRE by taking sample test questions or by purchasing and taking the MPRE online practice exam.[45]

- The test consists of 60 multiple-choice questions, only 10 of which are scored. You will have two hours to complete the test. Each question presents a hypothetical set of facts followed by a question. You must pick the best possible answer to the question from the four options presented.[44]

-

2

Register for the MPRE. You can take the MPRE in August, November, or March each year. The fee for the exam is $80 if you register by the regular deadline, or $160 if you register by the late deadline.[46]

- You will receive an admission ticket, which will indicate your test date and assigned testing center.

- You must complete the photo identification section of the admission ticket and attach a passport-type photograph of yourself that was taken within the last six months.[47]

-

3

Take the MPRE. To be admitted to practice law in California, you must receive a scaled score of 86.00 or greater.[48]

- On your test day, report to your assigned testing center at the time listed on your admission ticket to take the exam.

- You should try to arrive at least a half hour before the test begins so you can get checked in, and to give yourself some time because late arrivals won’t be admitted.

- You must bring a government-issued photo ID, with a first and last name that match the first and last name on your admission ticket.

- Review the list of prohibited items before you enter the testing center, and if you have anything with you that won’t be allowed, such as a mobile phone or a watch, leave it at home or in your car.[49]

Advertisement

-

1

Study for the Bar exam. In addition to your four years of law office study, you should consider taking a Bar prep course to learn how to succeed at the Bar exam itself.

- Bar prep courses typically offer a combination of in-person and online instruction over several weeks, and cost a few thousand dollars.[50]

- Bar prep courses boast far higher passage rates than the state averages. For example, Themis states that 75 percent of first-time test takers who completed their program passed the California bar.[51]

- Bar prep courses typically offer a combination of in-person and online instruction over several weeks, and cost a few thousand dollars.[50]

-

2

Understand that you probably won’t pass. In July of 2014, four candidates took the California Bar for the first time after completing the four year study program. None of them passed.[52]

- Of the 23 exam takers who were on their second or third attempt to pass the bar, only one passed.[53]

- Of the 23 exam takers who were on their second or third attempt to pass the bar, only one passed.[53]

-

3

Apply to take the Bar exam. Once you’ve completed your four years of study, you can apply to take the California Bar exam[54]

by filling out the application and paying the $645 fee to take the California Bar as a general applicant.[55]

- The exam is administered in July and February of each year. If you file your application in April for the July exam, or in November for the February exam, you’ll pay an additional $50 late filing fee. Anytime later, up until the final filing deadline, you can only apply if you pay an additional $250.[56]

- If you want to use a laptop for the exam, you’ll pay an additional fee of $146. You should decide if you want to use a laptop when you initially file your application, because if you change your mind and decide later that you want to use one, you’ll have to pay an additional $15 late laptop fee.[57]

- The exam is administered in July and February of each year. If you file your application in April for the July exam, or in November for the February exam, you’ll pay an additional $50 late filing fee. Anytime later, up until the final filing deadline, you can only apply if you pay an additional $250.[56]

-

4

Take the Bar exam. The California General Bar Examination consists of a written section that includes six essay questions and two performance tests along with the 200 multiple-choice questions for the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE).[58]

- For example, the July 2014 examination included essays on contracts and remedies, evidence, business associations and professional responsibility, criminal law and procedure, trusts and community property, and torts. The two performance tests were writing an objective memorandum and writing a persuasive brief.[59]

- You will receive an admissions ticket that includes the dates and times of your exam and the location of your assigned testing center. You also will receive a bulletin that describes the schedule for testing each day and provides a list of items prohibited at the testing center.[60]

- Carefully review the rules regarding items such as mobile phones that are prohibited in the testing center, and make sure you don’t bring anything with you that isn’t allowed.[61]

- The California Bar exam takes three days. Each of those days begins at 8:30 a.m. and consists of two three-hour testing sessions broken up by a lunch break.[62]

- For example, the July 2014 examination included essays on contracts and remedies, evidence, business associations and professional responsibility, criminal law and procedure, trusts and community property, and torts. The two performance tests were writing an objective memorandum and writing a persuasive brief.[59]

-

5

Pass the Bar exam. To pass the exam, you must have a total scaled score of 1440 points out of a possible 2000 points.[63]

- Your result letter will include your raw scores on each of the eight parts of the exam, your total raw and scaled written score, your MBE scaled score, and your total scaled score.[64]

- Your result letter will include your raw scores on each of the eight parts of the exam, your total raw and scaled written score, your MBE scaled score, and your total scaled score.[64]

Advertisement

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 162,040 times.

Did this article help you?

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow’s weekly email newsletter

Subscribe

You’re all set!

Download Article

Download Article

If you want to be a lawyer, you have to pass the Bar exam in the state where you want to practice – and usually, that means you have to graduate from law school first. California is one of only a handful of states that allows people to take the bar exam without going to law school. However, you should keep in mind that your odds of actually passing are extremely low. In law school, you learn to think like a lawyer and you use that critical thinking to help increase your likelihood of passing the bar exam. The California Bar exam has a passage rate of less than 50 percent, and that rate shrinks to less than 5 percent among exam takers who didn’t graduate from law school.[1]

Even if you are fortunate enough to pass the bar exam without a law degree, it is nearly impossible to be hired from any law firm without graduating from an ABA-accredited law school.

-

1

Complete the required pre-legal education. Before you start studying law, you must finish at least two years of college work, or take the CLEP (College Level Equivalency Program) test.[2]

- Two years equates to at least 60 semester hours or 90 quarter hours of credit.

- You must have a grade average high enough to qualify for a degree, had you completed the full four years.[3]

-

2

Find an attorney or judge to supervise you as your mentor. It’s up to you to find someone willing to mentor you for the next four years without receiving any pay or even continuing education credit.

- The attorney or judge you choose must be admitted to the active practice of law in California, and have been in good standing for at least five years.

- You will not be working for your mentor. Rather, you will be following a course of study proposed by the attorney or judge, who will personally supervise you at least five hours a week.[4]

- Try to study law under an attorney who practices the same type of law you want to practice after you pass the bar exam.[5]

- Your mentor also must examine you at least once a month on the material you studied that month.

- Once every six months, your mentor will report to the Committee of Bar Examiners the hours you studied each week and the subjects and materials you studied.[6]

Advertisement

-

3

Register as a law student. Before you submit any other forms, you must apply with the State Bar of California Office of Admissions to register as a law student.[7]

Your application for registration must include a $113 fee.[8]

-

4

Submit a Notice of Intent to Study in a Law Office or Judge’s Chambers. Within 30 days[9]

of the day you start your study program, you must submit the state’s form along with a $150 fee.[10]

-

5

Plan your program of study. Since you have to pass the Bar exam before you can start practicing law, your study should focus primarily on Bar subjects.

- Subjects tested on the California Bar include business associations, civil procedure, community property, constitutional law, contracts, criminal law and procedure, evidence, real property, torts, and wills and trusts.[11]

- You must study at least 18 hours a week for 48 weeks to acquire credit for one year of legal study. You must have at least four years of legal study at a law office or judge’s chambers before you can take the California Bar exam.[12]

- To qualify, your study hours must happen in the law office or the judge’s chambers during regular business hours.[13]

- Within 30 days of the day you begin your study, your mentor must send the Committee of Bar Examiners an outline of your course of study. The Committee doesn’t critique this outline or oversee any of your work while you study.[14]

- Subjects tested on the California Bar include business associations, civil procedure, community property, constitutional law, contracts, criminal law and procedure, evidence, real property, torts, and wills and trusts.[11]

-

6

Submit semi-annual reports. Within 30 days of the conclusion of a six-month period of study, you and your mentor must send a report of your studies for that time accompanied by a $100 fee.

- The report may include the hours you studied, the areas of law you covered and course materials you used, cases you read, exercises you completed, and evaluation of your performance on monthly exams.[15]

- The report may include the hours you studied, the areas of law you covered and course materials you used, cases you read, exercises you completed, and evaluation of your performance on monthly exams.[15]

Advertisement

-

1

Study for the First-Year Law Students’ Examination (FYLSX). After you’ve completed one year of legal education, you must take and pass the FYLSX, also known as the «Baby Bar.»[16]

- The FYLSX takes one day. During the morning session you have approximately four hours to answer four essay questions. After a lunch break, the test day concludes with a three-hour afternoon session during which you’ll answer 100 multiple-choice questions.[17]

- Since the exam covers contracts, criminal law, and torts, these subjects should be the focus of your first year of study.[18]

- Study aids and sample essay exam questions with answers are available from the Office of Admissions of the California Bar.

- The FYLSX takes one day. During the morning session you have approximately four hours to answer four essay questions. After a lunch break, the test day concludes with a three-hour afternoon session during which you’ll answer 100 multiple-choice questions.[17]

-

2

Apply to take the FYLSX. The exam is offered in June and October each year, and must be taken either in Los Angeles or San Francisco.[19]

- Your application must be accompanied by a fee of $566.[20]

- If you file your application after the regular deadline passes, expect to pay additional late filing fees which can be as much as $200.[21]

- After you apply, your mentor will be sent a certification form to prove you’ve completed a year of law study. You have until the final eligibility deadline to submit your certification.[22]

- Your application must be accompanied by a fee of $566.[20]

-

3

Take the FYLSX. A passing score on the exam is a total score of 560 or higher.

- Your multiple-choice score consists of the number of questions you answered correctly, converted to a 400-point scale that adjusts for variations in difficulty across the different versions of the test.

- Your total raw essay score ranges between 160 and 400 points. This score is converted to the same 400-point scale used for the multiple-choice questions.

- Your converted essay scores and converted multiple-choice scores are added together to produce your total score.[23]

- If you don’t pass the Baby Bar on the first try, you can try again. The California Bar gives you a total of three chances to pass the exam. If it takes you more than three attempts, you only get credit for a single year of legal education – which means you wouldn’t get credit for any time you spent studying while you were retaking the FYLSX.[24]

Advertisement

-

1

Gather materials necessary to complete your application. The Committee conducts a thorough and intense background examination before determining you have sufficient moral character to practice law in California.

- For example, to complete the application you will need to list employment history going back to your 18th birthday. You may not recall the addresses of places you worked part-time, or the names of your supervisors. You’ll need to track down this information.

- Read the entire application through once before you answer any questions, and make notes of information you need. Then find that information before you sit down to fill out the application.[25]

-

2

Have a set of fingerprints made. If you live in California, you must submit fingerprints using California Live Scan Technology. If you live outside the state you can submit a fingerprint card along with a request for exemption.[26]

-

3

Complete your application. You must answer all questions on the application completely and correctly or your application will be considered incomplete and won’t be reviewed.[27]

-

4

Submit your application. If you have completed the application online, you must mail a hard copy to the Office of Admissions in Los Angeles within 30 days of submitting it online.[28]

- Use the checklist that prints with your application to double-check and ensure that all the forms and pages have been completed, and that you’ve signed all the forms that require your signature.[29]

- Your application will be considered abandoned if it isn’t complete within 60 days of filing.[30]

- You can file your application at any time after you begin your law study,[31]

but the Committee recommends you file at least eight to ten months prior to the date you anticipate being admitted to practice law in California.[32]

- Your application must be accompanied by a filing fee of $525.[33]

- The Committee will send confidential reference questionnaires to any references, employers, or law schools that are listed on your application.

- Use the checklist that prints with your application to double-check and ensure that all the forms and pages have been completed, and that you’ve signed all the forms that require your signature.[29]

-

5

Wait for a determination on your application. It takes at least 180 days for the Committee to complete the background check, finish processing an application, and make a decision.[34]

- You will receive a notice from the Committee within 180 days. Either the notice will tell you the determination is positive, or it will tell you that the Committee requires further information from you, a government agency, or another source. If the Committee requests additional information from you, you should submit it promptly.[35]

- If the Committee still has questions about or issues with your application, you may receive an invitation to an informal hearing. You don’t have to attend, and it won’t affect the Committee’s decision if you decide not to go.[36]

However, attending the hearing could allow you to clear up problems that are keeping you from getting a positive determination.

- You will receive a notice from the Committee within 180 days. Either the notice will tell you the determination is positive, or it will tell you that the Committee requires further information from you, a government agency, or another source. If the Committee requests additional information from you, you should submit it promptly.[35]

-

6

Update your application as necessary until you are admitted to the Bar. Until you pass the Bar exam, you are responsible for amending your application when any of the information you provided changes, or you have new information that should be added. Failure to do so within 30 days of your knowledge of the change may result in the suspension of a positive determination.[37]

- To submit amendments, you can either print your application and mark the places where changes need to be made, or send in a separate sheet of paper on which you’ve written the changes or additions down and signed it.[38]

- Amendments may be submitted with your hard copy application or mailed separately to the Los Angeles Office of Admissions.[39]

- To submit amendments, you can either print your application and mark the places where changes need to be made, or send in a separate sheet of paper on which you’ve written the changes or additions down and signed it.[38]

-

7

File for an extension. A positive moral character determination is valid for 36 months.[40]

If you haven’t passed the Bar in that time, you can submit an application for an extension along with a fee of $252.[41]

Advertisement

-

1

Study for the MPRE. The MPRE is administered and graded by the National Conference of Bar Examiners,[42]

and tests your understanding of the American Bar Association Model Rules of Professional Conduct, the ABA Model Rules of Judicial Conduct, and other court decisions or rules of procedure and evidence that deal with attorney ethics and professional conduct.[43]

- The test consists of 60 multiple-choice questions, only 10 of which are scored. You will have two hours to complete the test. Each question presents a hypothetical set of facts followed by a question. You must pick the best possible answer to the question from the four options presented.[44]

- In addition to reading the ABA Model Rules, you can study for the MPRE by taking sample test questions or by purchasing and taking the MPRE online practice exam.[45]

- The test consists of 60 multiple-choice questions, only 10 of which are scored. You will have two hours to complete the test. Each question presents a hypothetical set of facts followed by a question. You must pick the best possible answer to the question from the four options presented.[44]

-

2

Register for the MPRE. You can take the MPRE in August, November, or March each year. The fee for the exam is $80 if you register by the regular deadline, or $160 if you register by the late deadline.[46]

- You will receive an admission ticket, which will indicate your test date and assigned testing center.

- You must complete the photo identification section of the admission ticket and attach a passport-type photograph of yourself that was taken within the last six months.[47]

-

3

Take the MPRE. To be admitted to practice law in California, you must receive a scaled score of 86.00 or greater.[48]

- On your test day, report to your assigned testing center at the time listed on your admission ticket to take the exam.

- You should try to arrive at least a half hour before the test begins so you can get checked in, and to give yourself some time because late arrivals won’t be admitted.

- You must bring a government-issued photo ID, with a first and last name that match the first and last name on your admission ticket.

- Review the list of prohibited items before you enter the testing center, and if you have anything with you that won’t be allowed, such as a mobile phone or a watch, leave it at home or in your car.[49]

Advertisement

-

1

Study for the Bar exam. In addition to your four years of law office study, you should consider taking a Bar prep course to learn how to succeed at the Bar exam itself.

- Bar prep courses typically offer a combination of in-person and online instruction over several weeks, and cost a few thousand dollars.[50]

- Bar prep courses boast far higher passage rates than the state averages. For example, Themis states that 75 percent of first-time test takers who completed their program passed the California bar.[51]

- Bar prep courses typically offer a combination of in-person and online instruction over several weeks, and cost a few thousand dollars.[50]

-

2

Understand that you probably won’t pass. In July of 2014, four candidates took the California Bar for the first time after completing the four year study program. None of them passed.[52]

- Of the 23 exam takers who were on their second or third attempt to pass the bar, only one passed.[53]

- Of the 23 exam takers who were on their second or third attempt to pass the bar, only one passed.[53]

-

3

Apply to take the Bar exam. Once you’ve completed your four years of study, you can apply to take the California Bar exam[54]

by filling out the application and paying the $645 fee to take the California Bar as a general applicant.[55]

- The exam is administered in July and February of each year. If you file your application in April for the July exam, or in November for the February exam, you’ll pay an additional $50 late filing fee. Anytime later, up until the final filing deadline, you can only apply if you pay an additional $250.[56]

- If you want to use a laptop for the exam, you’ll pay an additional fee of $146. You should decide if you want to use a laptop when you initially file your application, because if you change your mind and decide later that you want to use one, you’ll have to pay an additional $15 late laptop fee.[57]

- The exam is administered in July and February of each year. If you file your application in April for the July exam, or in November for the February exam, you’ll pay an additional $50 late filing fee. Anytime later, up until the final filing deadline, you can only apply if you pay an additional $250.[56]

-

4

Take the Bar exam. The California General Bar Examination consists of a written section that includes six essay questions and two performance tests along with the 200 multiple-choice questions for the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE).[58]

- For example, the July 2014 examination included essays on contracts and remedies, evidence, business associations and professional responsibility, criminal law and procedure, trusts and community property, and torts. The two performance tests were writing an objective memorandum and writing a persuasive brief.[59]

- You will receive an admissions ticket that includes the dates and times of your exam and the location of your assigned testing center. You also will receive a bulletin that describes the schedule for testing each day and provides a list of items prohibited at the testing center.[60]

- Carefully review the rules regarding items such as mobile phones that are prohibited in the testing center, and make sure you don’t bring anything with you that isn’t allowed.[61]

- The California Bar exam takes three days. Each of those days begins at 8:30 a.m. and consists of two three-hour testing sessions broken up by a lunch break.[62]

- For example, the July 2014 examination included essays on contracts and remedies, evidence, business associations and professional responsibility, criminal law and procedure, trusts and community property, and torts. The two performance tests were writing an objective memorandum and writing a persuasive brief.[59]

-

5

Pass the Bar exam. To pass the exam, you must have a total scaled score of 1440 points out of a possible 2000 points.[63]

- Your result letter will include your raw scores on each of the eight parts of the exam, your total raw and scaled written score, your MBE scaled score, and your total scaled score.[64]

- Your result letter will include your raw scores on each of the eight parts of the exam, your total raw and scaled written score, your MBE scaled score, and your total scaled score.[64]

Advertisement

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 162,040 times.

Did this article help you?

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow’s weekly email newsletter

Subscribe

You’re all set!

Admission to the bar in the United States is the granting of permission by a particular court system to a lawyer to practice law in the jurisdiction and before those courts. Each U.S. state and similar jurisdiction (e.g. territories under federal control) has its own court system and sets its own rules for bar admission, which can lead to different admission standards among states. In most cases, a person is «admitted» or «called» to the bar of the highest court in the jurisdiction and is thereby authorized to practice law in the jurisdiction. Federal courts, although often overlapping in admission standards with states, set their own requirements for practice in each of those courts.

Typically, lawyers seeking admission to the bar of one of the U.S. states must earn a Juris Doctor degree from a law school approved by the jurisdiction, pass a bar exam administered by the regulating authority of that jurisdiction, pass a professional responsibility examination, and undergo a character and fitness evaluation. However, there are exceptions to each of these requirements.

A lawyer who is admitted in one state is not automatically allowed to practice in any other. Some states have reciprocal agreements that allow attorneys from other states to practice without sitting for another full bar exam; such arrangements differ significantly among states and among federal courts.

Terminology[edit]

The use of the term «bar» to mean «the whole body of lawyers, the legal profession» comes ultimately from English custom. In the early 16th century, a railing divided the hall in the Inns of Court, with students occupying the body of the hall and readers or Benchers on the other side. Students who officially became lawyers were «called to the bar», crossing the symbolic physical barrier and thus «admitted to the bar».[1] Later, this was popularly assumed to mean the wooden railing marking off the area around the judge’s seat in a courtroom, where prisoners stood for arraignment and where a barrister stood to plead. In modern courtrooms, a railing may still be in place to enclose the space which is occupied by legal counsel as well as the criminal defendants and civil litigants who have business pending before the court.

History[edit]

The first bar exam in what is now the United States was instituted by Delaware Colony in 1763, as an oral examination before a judge. Many other American colonies soon followed suit.[2] In the early United States, most states’ requirements for admission to the bar included a period of study under a lawyer or judge (a practice called «reading the law») and a brief examination.[3] Examinations were generally oral, and applicants were sometimes exempted from the examination if they had clerked in a law office for a certain number of years.[4] During the 19th century, admission requirements became lower in many states. Most states continued to require both a period of apprenticeship and some form of examination, but these periods became shorter and examinations were generally brief and casual.[4]

After 1870, law schools began to emerge across the United States as an alternative to apprenticeship. This rise was accompanied by the practice of diploma privilege, wherein graduates of law schools would receive automatic admission to the bar. Diploma privilege reached its peak between 1879 and 1921.[4] In most states, diploma privilege only applied to those who had graduated law school in the state where they practiced.[5] Examinations continued to exist during this period as requirements for those ineligible for diploma privilege, and were often administered by committees of attorneys.[2] Between 1890 and 1920, most states replaced oral examinations with written bar examinations.[4] Written examinations became commonplace as lawyers began to practice in states other than those where they were trained.[3][4]

In 1921, the American Bar Association formally expressed a preference for required written bar examinations in place of diploma privilege for law school graduates. In subsequent decades, the prevalence of diploma privilege declined deeply.[4][5] By 1948, only 13 law schools in 9 states retained diploma privilege. By 1980, only Mississippi, Montana, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wisconsin honored diploma privilege.[5][6] As of 2020, only Wisconsin allows J.D. graduates of accredited law schools to seek admission to the state bar without passing a bar examination.[7][8][9]

Admission requirements[edit]

Today, each state or U.S. jurisdiction has its own rules which are the ultimate authority concerning admission to its bar. Generally, admission to a bar requires that the candidate do the following:

- Earn a Juris Doctor degree or read law

- Pass a professional responsibility examination or equivalent requirement

- Pass a bar examination (except in cases where diploma privilege is allowed)

- Undergo a character and fitness certification

- Formally apply for admission to a jurisdiction’s authority responsible for licensing lawyers and pay required fees

Educational requirement[edit]

Most jurisdictions require that candidates earn a Juris Doctor degree from an approved law school, usually meaning a school accredited by the American Bar Association (ABA).[10][a] Exceptions include Alabama, California,[11] Connecticut, Massachusetts, West Virginia, and Tennessee, which allow individuals to take the bar exam upon graduation from law schools approved by state bodies but not accredited by the ABA. The state of New York makes special provision for persons educated to degree-level in common law from overseas, with most LLB degree holders being qualified to take the bar exam and, upon passing, be admitted to the bar.[12] In California, certain law schools «registered» with the Committee of Bar Examiners of the State Bar of California (CBE)[13] are authorized to grant Juris Doctor degrees although they are not accredited by the ABA or CBE. Students at these schools must take and pass the First-Year Law Students’ Examination (commonly referred to as the «Baby Bar») administered by the CBE, and may continue their studies to obtain their J.D. degree upon passage of this exam.[11]

A few jurisdictions (California, Maine, New York, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia) allow applicants to study under a judge or practicing attorney for an extended period of time rather than attending law school.[14][15][16] This method is known as «reading law» or «reading the law». New York allows applicants who are reading the law, but only if they have at least one year of law school study.[17] Maine allows students with two years of law school to serve an apprenticeship in lieu of completing their third year. New Hampshire’s only law school has an alternative licensing program that allows students who have completed certain curricula and a separate exam to bypass the regular bar examination.[18] Until the late 19th century, reading the law was common and law schools were rare. For example, Abraham Lincoln did not attend law school, and did not even read with anyone else, stating in his autobiography that he «studied with nobody».[19]

The American legal system is unusual in that it has no formal apprenticeship or clinical training requirements prior to admission to the bar, with a few exceptions. Delaware requires that candidates for admission to the bar serve five months in a clerkship with a lawyer in the state.[20] Vermont had a similar requirement but eliminated it in 2016.[21] Washington requires, since 2005, that applicants must complete a minimum of four hours of approved pre-admission education.[22][23] Some law schools have tried to rectify this lack of experience by requiring supervised «Public Service Requirements» of all graduates.[24] States that encourage law students to undergo clinical training or perform public service in the form of pro bono representation may allow students to appear and practice in limited court settings under the supervision of an admitted attorney.[b]

Professional responsibility requirement[edit]

In all jurisdictions except Puerto Rico and Wisconsin, candidates must pass the Multistate Professional Responsibility Examination (MPRE), which covers the professional responsibility rules governing lawyers.[27] This test is not administered separately from bar examinations, and most candidates usually sit for the MPRE while still in law school, right after studying professional responsibility (a required course in all ABA-accredited law schools). Some states require that a candidate pass the MPRE before being allowed to sit for the bar exam. Connecticut and New Jersey waive the MPRE for candidates who have received a grade of C or better in a law school professional ethics class.[citation needed]

Bar examination requirement[edit]

In all jurisdictions except Wisconsin, candidates are required to pass a bar examination, usually administered by the state bar association or under the authority of the supreme court of the particular state. Wisconsin is the only state that does not require the bar examination; graduates of ABA-accredited law schools in the state may be admitted to the state bar through diploma privilege.

State bar examinations are usually administered by the state bar association or under the authority of the supreme court of the particular state. In 2011, the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) created the Uniform Bar Examination (UBE), which has since been adopted by 37 jurisdictions (out of a possible 56).[28] The UBE consists of three parts: the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE), a standardized test consisting of 200 multiple-choice questions; the Multistate Essay Examination (MEE), a uniform though not standardized test that examines a candidate’s ability to analyze legal issues and communicate them effectively in writing; and the Multistate Performance Test (MPT), a «closed-universe» test in which each candidate is required to perform a standard lawyering task, such as a memo or brief.

Non-UBE jurisdictions usually also include a combination of multiple-choice questions, essay questions, and performance tests. Many jurisdictions use some NCBE-created components. For example, all jurisdictions except Louisiana and Puerto Rico use the MBE. Many states also use state-specific content is usually included in the examination, such as essays in Washington, Minnesota and Massachusetts. Some states, such as Florida, include both essays and multiple-choice questions in their state-specific sections; Virginia uses full essays and short-answer questions in its state-specific section.[citation needed]

Character and fitness requirement[edit]

Most states also require an applicant to demonstrate good moral character. Character Committees look to an applicant’s history to determine whether the person will be fit to practice law in the future. This history may include prior criminal arrests or convictions, academic honor code violations, prior bankruptcies or evidence of financial irresponsibility, addictions or psychiatric disorders, sexual misconduct, prior civil lawsuits or driving history.[29] In recent years, such investigations have increasingly focused on the extent of an applicant’s financial debt, as increased student loans have prompted concern for whether a new lawyer will honor legal or financial obligations. For example, in early 2009, a person who had passed the New York bar and had over $400,000 in unpaid student loans was denied admission by the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division due to excessive indebtedness, despite being recommended for admission by the state’s character and fitness committee.[30] He moved to void the denial, but the court upheld its original decision in November 2009, by which time his debt had accumulated to nearly $500,000.[31] More recently, the Court of Appeals of Maryland rejected the application of a candidate who displayed a pattern of financial irresponsibility, applied for a car loan with false information, and failed to disclose a recent bankruptcy.[32]

When applying to take a state’s bar examination, applicants are required to complete extensive questionnaires seeking the disclosure of significant personal, financial and professional information. For example, in Virginia, each applicant must complete a 24-page questionnaire[33] and may appear before a committee for an interview if the committee initially rejects their application.[34] The same is true in the State of Maryland, and in many other jurisdictions, where the state’s supreme court has the ultimate authority to determine whether an applicant will be admitted to the bar.[35] In completing the bar application, and at all stages of this process, honesty is paramount. An applicant who fails to disclose material facts, no matter how embarrassing or problematic, will greatly jeopardize the applicant’s chance of practicing law.[29]

Formal admission[edit]

Once all prerequisites have been satisfied, an attorney must formally apply for admission. The mechanics of this final stage vary widely. For example, in California, the admittee simply takes an oath before any state judge or notary public, who then co-signs the admission form. Upon receiving the signed form, the State Bar of California adds the new admittee to a list of applicants recommended for admission to the bar which is automatically ratified by the Supreme Court of California at its next regular weekly conference; then everyone on the list is added to the official roll of attorneys. The State Bar also holds large-scale formal admission ceremonies in conjunction with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and the federal district courts, usually in the same convention centers where new admittees took the bar examination, but these are optional. In other jurisdictions, such as the District of Columbia, new admittees must attend a special session of court in person to take the oath of admission in open court; they cannot take the oath before any available judge or notary public.[citation needed]

A successful applicant is permitted to practice law after being sworn in as an officer of the Court; in most states, that means they may begin filing pleadings and appearing as counsel of record in any trial or appellate court in the state. Upon admission, a new lawyer is issued a certificate of admission, usually from the state’s highest court, and a membership card attesting to admission.[citation needed]

Two states are exceptions to the general rule of admission by the state’s highest court. In New York, admission is granted by one of the state’s four intermediate appellate courts corresponding generally to the Department of residence of the applicant; once admitted, however, the applicant can practice in any (non-federal) court in the state.[36] In Georgia, each new attorney is admitted to practice by the Superior Court of any county, typically the county in which he or she resides or desires to practice. The new attorney, although licensed to practice in any local trial court in the state, must separately seek admission to the Georgia Court of Appeals as well as the Georgia Supreme Court.[37]

In most states, lawyers are also issued a unique bar identification number. In states like California where unauthorized practice of law is a major problem,[clarification needed] the state bar number must appear on all documents submitted by a lawyer.[38]

Tactical considerations regarding admission in multiple states[edit]

Most attorneys seek and obtain admission only to the bar of one state, and then rely upon pro hac vice admissions for the occasional out-of-state matter. However, many new attorneys do seek admission in multiple states, either by taking multiple bar exams or applying for reciprocity. This is common for those living and working in metro areas which sprawl into multiple states, such as Washington, D.C. and New York City. Attorneys based in predominantly rural states or rural areas near state borders frequently seek admission in multiple states in order to enlarge their client base.

Note that in states that allow reciprocity, admission on motion may have conditions that do not apply to those admitted by examination. For example, attorneys admitted on motion in Virginia are required to show evidence of the intent to practice full-time in Virginia and are prohibited from maintaining an office in any other jurisdiction. Also, their licenses automatically expire when they no longer maintain an office in Virginia.[39][40]

Types of state bar associations[edit]

Admission to a state’s bar is not necessarily the same as membership in that state’s bar association. There are two kinds of state bar associations:

Mandatory (integrated) bar[edit]

Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia require membership in the state’s bar association to practice law there.[41] This arrangement is called having a mandatory, unified, or integrated bar.

For example, the State Bar of Texas is an agency of the judiciary and is under the administrative control of the Texas Supreme Court,[42] and is composed of those persons licensed to practice law in Texas; each such person is required by law to join the State Bar by registering with the clerk of the Texas Supreme Court.[43]

Voluntary and private bar associations[edit]

A voluntary bar association is a private organization of lawyers. Each may have social, educational, and lobbying functions, but does not regulate the practice of law or admit lawyers to practice or discipline lawyers. An example of this is the New York State Bar Association.

There is a statewide voluntary bar association in each of the eighteen states that have no mandatory or integrated bar association. There are also many voluntary bar associations organized by geographic area (e.g., Chicago Bar Association), interest group or practice area (e.g., Federal Communications Bar Association), or ethnic or identity community (e.g., Hispanic National Bar Association).

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a nationwide voluntary bar association with the largest membership in the United States. The National Bar Association was formed in 1925 to focus on the interests of African-American lawyers after they were denied membership by the ABA.[44]

Federal courts[edit]

Admission to a state bar does not automatically entitle an individual to practice in federal courts, such as the United States district courts or United States court of appeals. In general, an attorney is admitted to the bar of these federal courts upon payment of a fee and taking an oath of admission. An attorney must apply to each district separately. For instance, a Texas attorney who practices in federal courts throughout the state would have to be admitted separately to the Northern District of Texas, the Eastern District, the Southern District, and the Western District. To handle a federal appeal, the attorney would also be required to be admitted separately to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for general appeals and to the Federal Circuit for appeals that fall within that court’s jurisdiction. As the bankruptcy courts are divisions of the district courts, admission to a particular district court usually includes automatic admission to the corresponding bankruptcy court. The bankruptcy courts require that attorneys attend training sessions on electronic filing before they may file motions.

Some federal district courts have extra admission requirements. For instance, the Southern District of Texas requires attorneys seeking admission to attend a class on that District’s practice and procedures. The District of Puerto Rico has administered its own bar exam since 2004, part of which is an essay which tests for English proficiency. For some time, the Southern District of Florida administered an entrance exam, but that requirement was eliminated by Court order in February 2012.[45] The District of Rhode Island requires candidates to attend classes and to pass an examination.

An attorney wishing to practice before the Supreme Court of the United States must apply to do so, must be admitted to the bar of the highest court of a state for three years, must be sponsored by two attorneys already admitted to the Supreme Court bar, must pay a fee and must take either a spoken or written oath.[46]

Various specialized courts with subject-matter jurisdiction, including the United States Tax Court, have separate admission requirements. The Tax Court is unusual in that a non-attorney may be admitted to practice. However, the non-attorney must take and pass an examination administered by the Court to be admitted, while attorneys are not required to take the exam. Most members of the Tax Court bar are attorneys.

Admission to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit is open to any attorney admitted to practice and in good standing with the U.S. Supreme Court, any of the other federal courts of appeal, any federal district court, the highest court of any state, the Court of International Trade, the Court of Federal Claims, the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, or the District of Columbia Court of Appeals. An oath and fee are required.[47]

Some federal courts also have voluntary bar associations associated with them. For example, the Bar Association of the Fifth Federal Circuit, the Bar Association of the Third Federal Circuit, or the Association of the Bar of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit all serve attorneys admitted to practice before specific federal courts of appeals.

District Court Reciprocity[edit]

United States District Court reciprocity map

56 districts (around 60% of all district courts) require an attorney to be admitted to practice in the state where the district court sits. The other 39 districts (around 40% of all district courts) extend admission to certain lawyers admitted in other states, although conditions vary from court to court. Only 13 districts extend admission to attorneys admitted to any U.S. state bar.[48] This requirement is not necessarily consistent within a state. For example, in Ohio, the Southern District generally requires membership in the Ohio state bar for full admission,[49] while full admission to the Northern District is open to all attorneys in good standing with any U.S. jurisdiction.[50][51] In the Northern District of Ohio, admitted attorneys need not maintain an office in the district, or associate with a local attorney, unless ordered to do so by the court.[50][51] The District of Vermont requires membership in the Vermont State Bar or membership in the Bar of a federal district court in the First and Second Circuits.[52] The District of Connecticut, within the Second Circuit, will admit any member of the Connecticut bar or of the bar of any United States District Court.[53]

Patent practice[edit]