Crime is a violation of a law that forbids or commands an activity. Such crimes as murder, rape, arson are on the books of every country. Because crime is a violation of public order, the government prosecutes criminal cases.

Courts decide both criminal and civil cases. Civil cases stem from disputed claims to something of value. Disputes arise from accidents, contractual obligations, and divorce, for example.

Most countries make a rather clear distinction between civil and criminal procedures. For example, an English criminal court may force a defendant to pay a fine as punishment for his crime, and he may sometimes have to pay legal costs of the prosecution. But the victim of the crime pursues his claim for compensation in a civil, not a criminal, action.

Criminal and civil procedures are different. Although some systems, including English, allow a private citizen to bring a criminal prosecution against another citizen, criminal actions are nearly always started by the state. Civil actions, on the other hand, are usually started by individuals.

Some courts, such as the English Magistrates Courts and the Japanese Family Court, deal with both civil and criminal matters. Others, such as the English Crown Court, deal exclusively with one or the other.

In Anglo-American law, the party bringing a criminal action (that is, in most cases the state) is called the prosecution, but the party bringing a civil action is the plaintiff. In both kinds of action the other party is known as the defendant. A criminal case against a person called Ms. Brown would be described as «The People vs. (versus, or against) Brown» in the United States and «R. (Regina, that is, the Queen) vs. Brown» in England. But a civil action between Ms. Brown and Mr. Smith would be «Brown vs. Smith” if it was started by Brown and «Smith vs. Brown» if it was started by Mr. Smith.

Evidence from a criminal trial is not necessarily admissible as evidence in a civil action about the same matter. For example, the victim of a road accident does not directly benefit if the driver who injured him is found guilty of the crime of careless driving. He still has to prove his case in a civil action. In fact he may be able to prove his civil case even when the driver is found not guilty in the criminal trial.

Once the plaintiff has shown that the defendant is liable, the main argument in a civil court is about the amount of money, or damages, which the defendant should pay to the plaintiff.

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

Преступление является нарушением закона, который запрещает или команды действие. Такие преступления, как убийство, изнасилование, поджог находятся на книги в каждой стране. Поскольку преступление представляет собой нарушение общественного порядка, правительство осуществляет судебное преследование уголовных дел. Суды принимают решения уголовных и гражданских дел. Гражданские дела вытекают из спорных претензий к что-то ценное. Споры возникают от несчастных случаев, договорные обязательства и развода, например. Большинство стран сделать довольно четкое различие между гражданской и уголовной процедуры. Например английский уголовный суд может принудить ответчика уплатить штраф в качестве наказания за его преступления, и он иногда, возможно, придется оплатить судебные издержки судебного преследования. Но жертвы преступления преследует его иск о компенсации в гражданском, не уголовного, действий. Уголовные и гражданские процедуры различны. Хотя некоторые системы, включая английский, позволяют частное лицо довести уголовное преследование против другого гражданина, преступные действия почти всегда запускаются государством. С другой стороны, гражданских действий, обычно запускаются отдельными лицами. Некоторые суды, например, английские суды магистратов и японские семейного суда, дело с гражданским и уголовным делам. Другие, такие как английский суд короны, занимаются исключительно один или другой. В англо-американском праве, сторона, подавшая уголовное дело (то есть, в большинстве случаев государства) называется обвинения, но партия возбуждения гражданского иска является истцом. В обоих видах действий другой стороны известен как ответчик. Уголовное дело против лица, привлекаемого г-жа Браун будет описано как «народ против (против или против) Браун» в Соединенных Штатах и «Р. (Регина, то есть, королева) vs. Браун» в Англии. Однако гражданский иск между г-ном Смитом и г-жа Браун будет «Браун vs. Смит», если он был запущен Браун и «Смит против Брауна», если он был запущен г-ном Смитом. Свидетельство от уголовного разбирательства не обязательно приемлемым в качестве доказательства в гражданский иск о тот же вопрос. Например жертва дорожно-транспортного происшествия не пользу непосредственно, если водитель, кто ранен его виновным преступления неосторожное поведение на дорогах. Он до сих пор доказать свою правоту в гражданский иск. В действительности он может иметь возможность доказать его гражданское дело даже тогда, когда драйвер не будет найден виновным в уголовном процессе. После того, как истец показал, что ответчик несет ответственность, главный аргумент в гражданском суде, о количестве денег, или повреждения, которые ответчик должен выплатить истцу.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Преступление является нарушением закона , который запрещает или команды активностью. Такие преступления , как убийство, изнасилование, поджог находятся на балансе каждой страны. Поскольку преступление является нарушением общественного порядка, правительство расследует уголовные дела.

Суды решают как уголовные и гражданские дела. Гражданские дела вытекают из оспариваемых требований к что — то ценное. Споры возникают в результате несчастных случаев, договорных обязательств, и развод, например.

Большинство стран делают довольно четкое различие между гражданским и уголовным процедурам. Например, английский уголовный суд может вынудить ответчика выплатить штраф в качестве наказания за его преступления, и он может иногда придется платить судебные издержки обвинения. Но жертва преступления преследует его требование о компенсации в гражданском, а не уголовного, действия.

Уголовные и гражданские процедуры различны. Хотя некоторые системы, включая английский, позволяют частное лицо возбудить уголовное преследование в отношении другого гражданина, преступные действия почти всегда начинались государством. Гражданские иски, с другой стороны, обычно запускаются отдельными лицами.

Некоторые суды, такие как английский судах магистратов и японском суде по семейным делам, имеют дело с гражданским и уголовным делам. Другие, такие как английский коронного суда, дело исключительно с одной или другой стороны .

В англо-американском праве, партия в результате чего уголовное дело (то есть, в большинстве случаев государство) называется обвинение, но партия в результате чего гражданское действие истец. В обоих видах действия другая сторона известна в качестве ответчика. Возбуждено уголовное дело в отношении лица , называется г — жа Браун будет описана как «Народ против (против или против) Браун» в Соединенных Штатах и «Р. (Regina, то есть, Королева) против Брауна» в Англии , Но гражданский иск между г — жи Браун и г — н Смит будет «Браун против Смита» , если он был запущен Браун и «Смит против Брауна» , если он был начат г — н Смит.

Данные из уголовного процесса не обязательно в качестве доказательства в гражданском деле о том же. Например, жертвой дорожно — транспортного происшествия непосредственно не выиграет , если водитель , который ранил его признан виновным в совершении преступления неосторожного вождения. Он все еще должен доказать свое дело в рамках гражданского иска. на самом деле он может быть в состоянии доказать свое гражданское дело даже тогда , когда водитель был признан невиновным в уголовном процессе.

После того, как истец показал , что ответчик несет ответственность, главный аргумент в гражданском суде о размере деньги, или ущерб, которые ответчик должен выплатить истцу.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

|

Practice Test 19 |

ЧАСТЬ 2 – ЧТЕНИЕ |

||||

|

In the first paragraph, the author implies that Jack is someone who |

|||||

|

14 |

|||||

|

A15 |

1 |

||||

|

is careless with his possessions. |

|||||

|

2 |

always expects the worst. |

||||

|

3 |

learns from experience. |

||||

|

4 |

is quite forgetful. |

||||

|

In |

the second paragraph, we learn that Jack |

||||

|

15 |

|||||

|

A16 |

1 |

didn’t go fishing very often. |

|||

|

2 |

didn’t take fishing very seriously. |

||||

|

3 |

had taught himself how to fish. |

||||

|

4 |

had only recently taken up fishing. |

||||

|

A1716 |

‘them’ (line 6, paragraph three) refers to Jack’s |

||||

|

1 |

week-day evenings. |

||||

|

2 |

work colleagues. |

||||

|

3 |

flatmates. |

||||

|

4 |

fishing trips. |

||||

|

A1817 |

When the writer says in paragraph four that Jack was ‘put out’ by his flatmates’ jokes, |

||||

|

it means he was |

|||||

|

1 |

puzzled. |

||||

|

2 |

encouraged. |

||||

|

3 |

annoyed. |

||||

|

4 |

amused. |

||||

|

In paragraph five, the writer suggests that Jack |

|||||

|

A1918 |

|||||

|

1 |

doubted the quality of his poems. |

||||

|

2 |

had been discouraged by others’ opinions of his poems. |

||||

|

3 |

didn’t really care what others thought of his poems. |

||||

|

4 |

dreamt of publishing a book of poems. |

||||

|

A2019 |

When the writer says that Jack ‘had high hopes’ in paragraph six, he means that he |

||||

|

1 |

thought he might be disappointed by his trip. |

||||

|

2 |

was looking forward to a relaxing afternoon. |

||||

|

3 |

felt that he would achieve a lot that day. |

||||

|

4 |

felt that his afternoon would improve his mood. |

||||

|

A2120 |

The writer suggests that Jack was having difficulty writing because |

||||

|

1 |

the day was too hot. |

||||

|

2 |

he got distracted by reading old poems. |

||||

|

3 |

he lacked inspiration. |

||||

|

4 |

he was more focused on fishing. |

153

ЧАСТЬ 3 – ГРАММАТИКА И ЛЕКСИКА Practice Test 19

1Прочитайте приведённый ниже текст. Преобразуйте, если необходимо, сло& ва, напечатанные заглавными буквами в конце строк, обозначенных номера& ми B4–B10, так, чтобы они грамматически соответствовали содержанию текста. Заполните пропуски полученными словами. Каждый пропуск соответствует отдельному заданию из группы B4–B10.

|

B5 |

will be |

|

B6 |

Have you got |

|

B7 |

has been waiting |

|

B8 |

picking |

|

B9 hadn’t been driving |

|

|

B10 |

will leave |

2 Прочитайте приведённый ниже текст. Преобразуйте, если необходимо, слова, напечатанные заглавными буквами в конце строк, обозначенных номерами В11–B16, так, чтобы они грамматически и лексически соответ& ствовали содержанию текста. Заполните пропуски полученными словами. Каждый пропуск соответствует отдельному заданию из группы В11–В16.

|

Chess |

||

|

Chess is a fun and |

challenging |

board game played between two players. To |

beat an opponent, a player has to move their chess pieces on a chequered board in order to try to capture their opponent’s king.

This is not a new game. It has been played competitively since the 16th century. The first official

|

chess |

B129) |

competition |

was held in Madrid in 1560 and was won by a priest, |

|

|

Father Ruy |

Lopez de Segura. Centuries later, in 1886, the first official World Chess |

|||

|

Championship |

took place. |

|||

|

10) ………………………… |

||||

|

B13 |

Russia has a long history with the game of chess. In fact, Russia has produced more chess

|

champions than any other country. The most 11)B14 |

amazing |

of these players |

is Garry Kasparov. He holds the record for the most victories won in a row by any chess player.

|

In 1989, he even played against |

a chess playing computer Deep Thought. He won |

||

|

easily |

|||

|

12)B15 |

fortunate |

||

|

. |

|||

|

However, he wasn’t so |

13)B16 |

in 1997 when he lost against a newer |

|

computer, Deep Blue.

Despite this, Kasparov still remains the best player in the history of Chess.

CHALLENGE

COMPETE

CHAMPION

AMAZE

EASY FORTUNE

154

|

Practice Test 19 |

ЧАСТЬ 3 – ГРАММАТИКА И ЛЕКСИКА |

3Прочитайте текст с пропусками, обозначенными номерами А22–А28. Эти номера соответствуют заданиям A22–A28, в которых представлены возмож& ные варианты ответов. Обведите номер выбранного вами варианта ответа.

The First Mobile Phone

|

On April 3, 1972, a man came out of the Hilton Hotel in New York, USA, and started walking |

……..14)A22 |

the street. He stopped, |

|

|

15)A23…….. |

a strange object against his ear and started talking into it. The man was Martin Cooper, General Manager of a major |

communications company, and he was making the world’s first telephone call on a mobile phone, nicknamed ‘the shoe’ because

of its unusual 16)A24…….. .

The reason Mr Cooper had gone to New York was to 17)A25…….. the new phone. The call he made was to Joe Engel who worked at a rival company. Engel was responsible 18)A26…….. the development of radiophones for cars. “I said that I was talking on a real mobile phone that I was holding in my hand,” Cooper reported. “I don’t remember what he said in 19)A27…….., but I’m sure he wasn’t happy.”

The quality of the call made that day was very good, because although New York had only one base station at the 20)A28…….., it was being used by only one user — Martin Cooper!

|

A22 |

1 |

to |

2 |

by |

3 |

down |

4 |

through |

|

A23 |

1 |

held |

2 |

pulled |

3 |

caught |

4 |

kept |

|

A24 |

1 |

build |

2 |

pattern |

3 |

model |

4 |

shape |

|

A25 |

1 |

introduce |

2 |

welcome |

3 |

insert |

4 |

begin |

|

A26 |

1 |

for |

2 |

of |

3 |

about |

4 |

to |

|

A27 |

1 |

explanation |

2 |

reply |

3 |

answer |

4 |

reaction |

|

A28 |

1 |

occasion |

2 |

point |

3 |

moment |

4 |

time |

ЧАСТЬ 4 – ПИСЬМО

C11 You have received a letter from your English speaking pen friend Jamie who writes:

… I just got a new computer for my birthday. I’m so excited about it! How about you – do you have a computer? What do you use computers for? What other high tech gadget would you like to have?

My latest news is that I’ve broken my arm …

Write a letter to Jamie. In your letter ● answer her questions

● ask 3 questions about her broken arm Write 100 140 words. Remember the rules of letter writing.

C22 Comment on the following statement.

“Living in a city has many disadvantages. Living in the country also brings its own share of problems.”

What is your opinion? Would you rather live in the city or the country? Write 200 250 words.

Use the following plan:

●write an introduction (state the problem/topic)

●express your personal opinion and give reasons for it

●give arguments for the other point of view and explain why you don’t agree with it

●draw a conclusion

155

|

ЧАСТЬ 1 – АУДИРОВАНИЕ |

Practice Test 20 |

1 Вы услышите высказывания шести людей о различной еде. Установите соответствие между высказываниями каждого говорящего 1–6 и утверж дениями, данными в списке A–G. Используйте каждое утверждение, обозна ченное буквой, только один раз. В задании есть одно лишнее утверждение.

Вы услышите запись дважды. Занесите свои ответы в таблицу B1.

A I don’t have this food often because I know I shouldn’t.

B Preparing and eating this food relaxes me.

C I don’t like this food as much as most other people do.

D I only recently discovered this food.

E I eat too much of this food.

F I’ve changed my mind about this food.

G This food brings back happy memories for me.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

B1 A |

C |

G |

D |

F |

B |

2Вы услышите беседу двух друзей об игре на музыкальных инструментах. Определите, какие из приведённых утверждений А1–А7 соответствуют содержанию текста (1– True), какие не соответствуют (2 – False) и о чём в тексте не сказано, то есть на основании текста нельзя дать ни положи тельного, ни отрицательного ответа (3 – Not stated). Вы услышите запись дважды. Обведите правильный ответ.

|

A17 |

Tim was advised not to learn to play the violin. |

||||||

|

1 |

True |

2 |

False |

3 |

Not stated |

||

|

Tim thought learning to play the violin would be easy. |

|||||||

|

A28 |

|||||||

|

1 |

True |

2 |

False |

3 |

Not stated |

A39 Chloe plays the piano really well.

1 True 2 False 3 Not stated

A410 Tim’s parents made him start having music lessons.

|

1 True |

2 False |

3 Not stated |

A511 Chloe did not like her music teacher.

|

1 |

True |

2 |

False |

3 |

Not stated |

|||

|

Tim doesn’t think that he practises |

a lot. |

|||||||

|

A612 |

||||||||

|

1 |

True |

2 |

False |

3 |

Not stated |

|||

|

Tim’s ambition is to join an orchestra. |

||||||||

|

A713 |

||||||||

|

1 |

True |

2 |

False |

3 |

Not stated |

|||

156

|

Practice Test 20 |

ЧАСТЬ 1 – АУДИРОВАНИЕ |

3Вы услышите мужчину, рассказывающего о смене своего рода деятельности. В заданиях А8–А14 обведите цифру 1, 2 или 3, соответствующую номеру выбранного вами варианта ответа. Вы услышите запись дважды.

|

A814 |

The narrator decided to make a career change because |

|||||||

|

1 |

his family wanted him to. |

|||||||

|

2 |

he no longer looked forward to work. |

|||||||

|

3 |

he wanted a job with less responsibility. |

|||||||

|

When the narrator started his dog walking business, he |

||||||||

|

A915 |

||||||||

|

1 |

had no trouble finding clients. |

|||||||

|

2 |

found his previous knowledge of business useful. |

|||||||

|

3 |

had to advertise more than expected. |

|||||||

|

The narrator says that he was surprised by |

||||||||

|

16 |

||||||||

|

A10 |

||||||||

|

1 |

how challenging running a business was. |

|||||||

|

2 |

how quickly his business became successful. |

|||||||

|

3 |

how many other dog walking businesses there were. |

|||||||

|

The narrator criticises |

||||||||

|

A1117 |

||||||||

|

1 |

dog owners who insist that he does things a certain way. |

|||||||

|

2 |

people who think he charges too much for his services. |

|||||||

|

3 |

other dog walkers who don’t take their job seriously. |

|||||||

|

The narrator believes his success is due to his |

||||||||

|

A1218 |

||||||||

|

1 |

high standards. |

|||||||

|

2 |

reasonable prices. |

|||||||

|

3 |

good fortune. |

|||||||

|

When the narrator says he gets most new clients ‘by word-of-mouth’, he means |

||||||||

|

A1319 |

||||||||

|

1 |

his employees spend a lot of time telling people about his business. |

|||||||

|

2 |

he is good at persuading people to use his services. |

|||||||

|

3 |

his current clients recommend him to other dog owners. |

|||||||

|

The narrator ends by saying that |

||||||||

|

A1420 |

||||||||

|

1 |

dog walking isn’t suitable for everyone. |

|||||||

|

2 |

he wishes he’d become a dog walker sooner. |

|||||||

|

3 |

there are more disadvantages to dog walking than people think. |

157

|

ЧАСТЬ 2 – ЧТЕНИЕ |

Practice Test 20 |

1Установите соответствие между заголовками A–Н и текстами 1–7. Занесите свои ответы в таблицу B2. Используйте каждую букву только один раз. В задании один заголовок лишний.

|

A |

An exciting find |

E |

The great escape |

|

B |

Getting close to nature |

F |

An unusual contest |

|

C |

Upcoming show |

G |

Competition time |

|

D |

An exciting adventure |

H |

Looking for a good read |

of pollution and traffic. Many of the families that are moving are also excited by the idea of having a garden where their children can play outdoors safely.

7 If you are looking for a wild ride, then white water rafting is for you. This thrilling extreme sport involves moving along rapids and fastmoving rivers in a five-man boat. It can be dangerous but if you’re careful and properly equipped it can be fantastic fun. People of all ages can enjoy this activity and there are many exciting locations where you can try it out.

similarities to the famous authors of the time.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

B2 C |

G |

H |

A |

B |

E |

D |

158

|

Practice Test 20 |

ЧАСТЬ 2 – ЧТЕНИЕ |

2 Прочитайте текст и заполните пропуски 1–6 частями предложений, обозначенными буквами A–G. Одна из частей в списке А–G лишняя. Занесите букву, обозначающую соответствующую часть предложения, в таблицу B3.

The Norse people lived from about 200 500 A.D. in northern Europe and Scandinavia. After 700 A.D., they began to travel to find new lands and subsequently lived in parts of Britain, Iceland, Greenland and Russia. From this period on, the Norse were known as Vikings.

There were many different Norse tribes and clans who spoke a variety of languages 1) ….. . Their family lives, jobs, houses and traditions were very similar and they had the same beliefs.

Most Norse people lived on small farms, 2) ….. .

These were from 5 to 7 metres wide and from 15 to 75 metres long. They usually had stone bases, wooden walls and dirt floors.

The Norse people lit fires in the rooms of their houses to give them light and heat and there were holes in the roof so that the smoke could escape. They had wooden benches to sit, eat, work and sleep on. Longhouses didn’t usually have windows.

In early Norse times, animals and people lived and worked together in the longhouses. Later, only

Aso portion sizes were several times larger than those of today

Band they put everything else in other buildings

Cand were mostly farmers, craftsmen or traders

Dbut they used honey to make food taste sweet

people lived in the longhouses 3) ….. . Several families often lived in the same longhouse and worked on the same farm.

Norse people mainly ate food from their own farms. Their diet consisted of meat, cereals, dairy produce, vegetables and fruits. They didn’t have sugar, 4) ….. . Those who lived near the sea, rivers or lakes ate fish. They used cereals to make bread and ale – a very popular drink.

Norse people used spears or bows and arrows to hunt wild animals. They caught deer, bears and boars, 5) ….. . In the north, they caught seals and walruses for their meat and skins.

Norse people usually ate in the morning and in the evening. They ate at a table, and used wooden bowls and spoons and drank from animal horns. The Norse people needed a lot of energy, 6) ….. .

The Norse people worked hard, but they also made time for leisure activities and celebrations.

E each of which had a longhouse

F but had a lot of things in common

Gas well as smaller animals like rabbits

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

B3 F |

E |

B |

D |

G |

A |

159

|

ЧАСТЬ 2 – ЧТЕНИЕ |

Practice Test 20 |

3Прочитайте рассказ и выполните задания А15–А21. В каждом задании обведите цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному вами варианту ответа.

The Journalist

concourse hoping to spot him among the crowd of bag-laden shoppers. “He will come, won’t he?” he thought to himself, biting his

. It would be the in journalism if the informer did turn up, and a huge

embarrassment for Toby if he failed to deliver the front page story he had promised the editor by midnight that night.

It had taken Toby nearly ten years to work his way up from his first job at a local paper to a desk at a national one. He’d mainly covered small local stories and was only just beginning to make his mark in the world of front page headlines. Most of the other reporters in the office had been there for years and found his

his big break would come.

When his chance did finally come, it took him completely by surprise. He had been working on a story about a government minister’s involvement in a national scandal. There were plenty of rumours flying around, but Toby hadn’t managed to get hold of any concrete evidence. Nobody wanted to talk. Then, one evening at a cocktail party, someone had approached him and said he could give him all the proof he needed.

Toby looked at his watch yet again, the knot of nervousness in the pit of his stomach beginning to turn to angry resentment. He didn’t care if he was young and inexperienced,

walk over him now, but the day would come when he would be in a position to take revenge. It was a moment before Toby realised the informer had slipped into the seat beside him at the table.

The last time Toby had seen him he’d been wearing an expensive tailored suit. Now, he was dressed in casual clothes to better fit in with the more humble surroundings. The informer halfsmiled at Toby and apologised for keeping him waiting as he pushed a fat envelope across the table. “You’ll find everything you need and

of a dazzling career in journalism for you.” Toby picked up the envelope and put it in his

briefcase, resisting the urge to rip it open and

to an illustrious career as a leading reporter at one of the country’s most respected national

cream cake. “Just one question before you go,” said Toby when he’d got his composure back. “You’ve been friends with the minister since your days at university. Why betray him now?” As the informer stood up to leave, he patted Toby on the shoulder. “Ah yes, friends,” he said. “Indeed, I’ve been very useful to him in his career these past forty years. Now it’s his

briefcase.

160

he realised the story involved someone he knew. another journalist offered to help him.

he managed to make the right contacts. he was unexpectedly offered information.

|

Practice Test 20 |

ЧАСТЬ 2 – ЧТЕНИЕ |

A1514 While in the shopping centre, Toby felt anxious about

1 being disappointed by someone.

2 losing someone in the crowd.

3 having made a mistake.

4 losing his job.

A1615 In the second paragraph, the writer suggests that Toby

1 was more ambitious than his colleagues.

2 respected and admired his colleagues.

3 didn’t get on well with his colleagues.

4 worked harder than his colleagues.

A1716 Toby’s chance to get his first big story came after 1 2 3

4

A1817 In the fourth paragraph, the writer implies that Toby didn’t notice the informer arriving because

1 he had decided that he wouldn’t come.

2 he was lost in thought.

3 he was approached from behind.

4 he was expecting him to arrive later.

A1918 ‘it’ (line 8, paragraph five) refers to

|

1 |

money that the informer gave Toby. |

|

2 |

the national newspaper. |

|

3 |

the news story. |

|

4 |

the contents of the envelope. |

A2019 When Toby received the envelope, he

1 decided to open it immediately.

2 felt himself begin to relax.

3 became suspicious about what was inside.

4 had difficulty in controlling his feelings.

A2120 The informer says that he betrayed the minister because 1 it would benefit him.

2 the minister had betrayed him in the past.

3 he owed Toby a favour.

4 he had never liked him.

161

ЧАСТЬ 3 – ГРАММАТИКА И ЛЕКСИКА Practice Test 20

1Прочитайте приведённый ниже текст. Преобразуйте, если необходимо, сло ва, напечатанные заглавными буквами в конце строк, обозначенных номера ми B4–B10, так, чтобы они грамматически соответствовали содержанию текста. Заполните пропуски полученными словами. Каждый пропуск соответствует отдельному заданию из группы B4–B10.

|

B4 had been working |

|

|

B5 |

Are you coming |

|

B6 |

was |

B7 walked/was walking

B8 had offered

2 Прочитайте приведённый ниже текст. Преобразуйте, если необходимо, слова, напечатанные заглавными буквами в конце строк, обозначенных номерами В11–B16, так, чтобы они грамматически и лексически соответ ствовали содержанию текста. Заполните пропуски полученными словами. Каждый пропуск соответствует отдельному заданию из группы В11–В16.

The Future of Mobile Phones

|

Mobile phone technology has come a(n) |

B11 |

extremely |

long way in a short time. In |

fact, it’s almost difficult to believe that just a few years ago, we only used mobile phones to make phone calls or send text messages.

Today, not only can you take pictures and shoot videos with your mobile, you can use it to send emails,

|

surf the Web, listen to music and even get 9)B12 |

directions |

|

. |

So, with mobile technology moving so quickly, it is interesting to think about what the average mobile

|

phone |

10)B13 |

user |

will be doing with their phone in the future. |

|

One very possible future |

11)B14 |

development |

is that a small chip will be put inside mobile |

phones so that people can use them as a credit or debit card. To pay for goods in a shop, you would simply hold the phone up to a special reader and your account would be charged.

You will probably also be able to use your mobile phone as a front door or car key, so you won’t have to carry your keys around anymore.

But the truly revolutionary changes will come when intelligent software allows mobiles to predict your

|

needs, learn your |

12)B15 |

behaviour |

and recognise your speech. |

||

|

So, it seems that soon |

mobile phones will become even more necessary to people’s |

||||

|

lives |

than they are today. |

||||

|

13) ………………………… |

|||||

|

B16 |

EXTREME

DIRECT

USE DEVELOP

BEHAVE

LIVE

162

Соседние файлы в предмете Английский язык

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

20.06.20148.88 Mб95Примеры резюме на английском языке.pdf

- #

- #

“This virus is no respecter of persons.”[i] Coronavirus is a pandemic of global proportions which some have termed the third world war.[ii] Due to the pandemic, quarantine measures have been put in place across the globe. While typically restriction of movement of free people would fall under a human rights violation, there is an exception for threats to a nation that pandemics fall under. Nonetheless this exception does not cover the human rights violations in the enforcement of quarantine measures which have been brought to light around the globe. This abusive policing is not new, but the media coverage in most cases is. In response, the U.N. in a resolution about the Coronavirus pandemic should include recommendations that address these abuses.

As of April 13, 2020 Coronavirus has been around for less than 6 months and has been contracted through person-to-person contact by people in over 200 countries.[iii] By contrast, HIV/AIDS was found in 1983, can only be contracted through specific activities where body fluids are present, and incidents—after 37 years—have only been found in 142 countries (however, 32 million have died).[iv] The most recent Ebola crisis lasted from 2014–2016, was transmitted through direct contact with infected fluids, and spanned across just three African nations.[v] When a pandemic, such as AIDS and Ebola have been deemed “a threat to international peace and security” the United Nations Security Council has been known to step in by adopting resolutions.[vi] Today, the U.N. Security Council is mulling over some draft resolutions in response to Coronavirus, but without U.N. guidance countries have imposed quarantine and social distancing measures on their own. It is the enforcement of such quarantine measures that has concerning human rights implications.

As of today, April 15, 2020, over one third of the world’s 7.8 billion people are on lockdown.[vii] In fact, more people are under lockdown today than were even alive during WWII.[viii] India has imposed a 21-day lockdown for its 1.3 billion citizens.[ix] Germany has banned meetings of more than two people.[x] This global lockdown has included 91% of all enrolled learners in the world.[xi]

These quarantine measures on their face, restricting the movement of free people, are a violation of the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[xii] The Declaration was adopted in 1948 in “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal inalienable rights of all members of the human family.”[xiii] Some of the listed enumerated rights that are violated by quarantine orders are, the right to: liberty,[xiv] freedom of movement,[xv] freedom of religion in community with others,[xvi] freedom of peaceful assembly and association,[xvii] work and protection against unemployment,[xviii] education,[xix] and freely participate in community.[xx] However, while quarantines may violate these rights the U.N. has said that in response to serious public health threats to the “life of a nation,” human rights law allows for restrictions on some rights. Those restrictions, however, must be justified on a legal basis as strictly necessary. This “strictly necessary” standard must: be based on scientific evidence that is not arbitrary nor discriminatory, be set for a determinant amount of time, maintain respect for human dignity, be subject to review, and be proportionate to the objective sought to achieve.[xxi] Putting quarantine measures in place from the worldwide medical communities’ recommendations to stop the spread of a global pandemic seems to be exactly this type of situation, but the implementation is not without its own set of problems.

While social distancing has been lauded as the method to “flatten the curve” (until a vaccine can be found) it is a refuge for the privileged that exacts a far heavier toll on the poor.[xxii] People in poor countries rely more heavily on daily hands on labor and informal sector employment to earn enough cash each day to feed their families, they live day-to-day and cannot afford to stockpile food and necessities, and they frequently do not have easy access to clean water. In impoverished places social distancing cuts off access to wages, food, and water that is not supplemented in any other way.[xxiii] Further, and what the remainder of this paper will focus on is the policing used to enforce the quarantine measures in the developing world which is often abusive, an impermissible violation of the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and an illustration of the colonial legacies still in place in the developing world.

Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights says, “no one shall be subject to torture or to cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment or punishment.” As reported above there are some articles of this declaration that can be suspended when “strictly necessary” for “the life of a nation,” however, Article 5 is not one of them. What follows is a survey of enforcement abuses taken from news articles documenting how the quarantine measures have been enforced around the world.

Filipino president Duterte told the country in a public address that lockdown violators could be shot.[xxiv] While there have not been any reports of anyone being shot, reports have alleged that police have put people in public animal cages, and subjected others to physical punishments which the police video and then post online to shame the violators.[xxv]

In Brazil, people found on the streets without a reason had their feet bound in the public square.[xxvi] This is occurring while the Brazilian president publicly criticizes the stay at home orders and actively contradicts the directions of Mayors and governors.[xxvii] Because of the inconsistent quarantine measures some criminal gangs have imposed there own “coronavirus curfew,” posting signs and using megaphones to tell citizens to stay at home “or else.”[xxviii] Police are also using helicopters to create sand storms to drive people off of the beaches.[xxix]

The South African police rounded up 1,000 homeless men and crammed them into a soccer stadium where they were assigned ten to a tent. Adequate social distancing would have required no more than two per tent. The homeless men interviewed said that the virus would spread like wildfire among this group, they would be safer “social distancing” by themselves on the street, and they were terrified they were sent there to die.[xxx] South African police also used physical punishments, water cannons, and rubber bullets on people violating restrictions.[xxxi]

Videos of quarantine violators from India and Pakistan show young and old men being forced to crawl, do squats, and being beaten.[xxxii] Sime people are also put into a stress position where they are made to hold there ears from between their legs and made to hop around.[xxxiii] In India migrant worker were sprayed with a chemical solution containing bleach to “disinfect them.”[xxxiv] Another migrant who was caught violating quarantine orders had the words “I have violated lock down restrictions, keep away from me” written on his forehead.[xxxv]

Amnesty International reported that in Iran possibly 36 prisoners were killed who were protesting in fear of their risk of contracting coronavirus. These protests sprung up in multiple prisons that had promised to release certain categories of prisoners due to the pandemic and then went back on their promise.[xxxvi]

There are other instances that disproportionately affect the poor but perhaps do not rise to the level of an Article 5 human rights violation. A Chinese-Australian working in Beijing was fired from her job and deported for going for a run.[xxxvii] The United Arab Emirates, Australia, Singapore, Austria, Hong Kong, and Britain have imposed fines exceeding $3K for violations.[xxxviii] India, Britain, Mexico, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Russia have threatened and imposed prison time for violators.[xxxix]

Just as the Locust Effect points out it is countries with police forces set up to maintain the control of the ruling class from colonial times that have the most widespread reports of police abuses during this time of quarantine enforcement. Tellingly, it is not the police tactics that have changed in these places, only the international spotlight on them that this pandemic has created. However, it is precisely because of this spotlight that the U.N. should use the extra latitude afforded in times of crisis to speak out against the abuses and call for their end. Member states recognize that interference in their private internal affairs can be overridden times where international security and peace are threatened, and this is just a time as that.[xl]

Currently the U.N. General Assembly is deadlocked over two competing proposed Coronavirus resolutions.[xli] One proposal with 130 member-state co-sponsors calls for international cooperation by exchanging information, scientific knowledge, and best practices.[xlii] The other proposal sponsored by Russia, with support from the Central African Republic, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela calls for abandoning trade wars, rejecting any implementation of protectionist measures, and the lifting of unilateral sanctions without U.N. Security Council approval.[xliii] In light of the ongoing police abuses that are happening globally in the developing world as countries try to implement quarantine orders the U.N. resolution should incorporate a section on human rights acknowledging everyone’s right to life, freedom from excessive force, torture and humiliation, the right to due process, and accountability to those standards.

During the West African Ebola pandemic, the West African Regional Office of the High Commission on Human Rights wrote an instructive memo expressing what should be contained in an Ebola resolution.[xliv] In this report they specifically recommended that a resolution should call for:

- Peacefully diffusing protests before they take place.

- Giving clear orders to security forces to refrain from excessive force and abuse of power. Give clear guidelines on what is reasonable force and what is not.

- Assurance that there will be independent investigations for human rights violations.

- Insure national and local laws are implemented in accordance with principals of due process.

- The allowance of religious and education programming on public television and radio to supplement the inability to meet for educational and religious purposes.

- Insurance that all quarantined people had access to food, water, sanitation, and medical assistance.

These measures even if adopted probably will not stop the bulk of human rights abuses happening due to this pandemic. However, just as the Locust Effect laid out the steps Georgia took to reform corruption, this resolution could be a good first step. The published abuses have already started to generate a grassroots social demand for change. This could be levied into some political movements that can identify the courageous reformers. Once the acute crisis is over this budding change could create the perfect window for NGO’s to come in and support local reformers attack corruption, clean house in the local criminal justice system, create new respect for the reformed system and win public trust.[xlv]

The problem of human rights abuses will not be solved overnight. They will probably not be solved in our lifetime, but in this peculiar time of global crisis the daily reports of abusive policing in the third world can be a catalyst for change. The U.N. is in a particularly well-placed

[ix] See One Third, supra note 6.

[x] Id.

[xi] See Everything We Know, supra note 7.

[xii] United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1949).

[xiii] Id. at preamble.

[xiv] Id. at article 3.

[xv] Id. at article 13.1.

[xvi] Id. at article 18.

[xvii] Id. at article 20.1.

[xviii] Id. at article 23.1.

[xix] Id. at article 26.1.

[xx] Id. at article 27.1.

[xxi] U.N. Commission on Human Rights, The Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, E/CN.4/1985/4 (Sept. 28, 1984), https://www.refworld.org/docid/4672bc122.html.

[xxii] There is an argument that developing nations should not impose the same quarantine measures as industrialized nations, that argument is beyond the scope of this paper. For an overview of the argument see Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak & Zachary Barnett-Howell, Poor Countries Need to Think Twice About Social Distancing, Foreign Pol’y (April 10, 2020), https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/10/poor-countries-social-distancing-co….

[xxiii] Id.

[xxxiii] Id.

[xxxiv] See Virus Laws, supra note 30.

[xxxviii] Id.

[xxxix] Id.

[xlii] Id.

[xliii] Id.

[xliv] West African Regional Office, A Human Rights Perspective into the Ebola Outbreak, United Nations (Sept. 2014), globalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/A-human-rights-perspective-into-the-Ebola-outbreak.pdf.

[xlv] Gary A. Haugen & Victor Boutros, Locust Effect, 262–267 (2014).

Задание №6332.

Чтение. ЕГЭ по английскому

Прочитайте текст и заполните пропуски A — F частями предложений, обозначенными цифрами 1 — 7. Одна из частей в списке 1—7 лишняя.

A constitution may be defined as the system of fundamental principles according to ___ (A). A good example of a written constitution is the Constitution of the United States, formed in 1787.

The Constitution sets up a federal system with a strong central government. Each state preserves its own independence by reserving to itself certain well-defined powers such as education, taxes and finance, internal communications, etc. The powers ___ (B) are those dealing with national defence, foreign policy, the control of international trade, etc.

Under the Constitution power is also divided among the three branches of the national government. The First Article provides for the establishment of the legislative body, Congress, and defines its powers. The second does the same for the executive branch, the President, and the Third Article provides for a system of federal courts.

The Constitution itself is rather short, it contains only 7 articles. And it was obvious in 1787 ___ (C). So the 5 th article lays down the procedure for amendment. A proposal to make a change must be first approved by two-thirds majorities in both Houses of Congress and then ratified by three quarters of the states.

The Constitution was finally ratified and came into force on March 4, 1789. When the Constitution was adopted, Americans were dissatisfied ___ (D). It also recognized slavery and did not establish universal suffrage.

Only several years later, Congress was forced to adopt the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, ___ (E). They guarantee to Americans such important rights and freedoms as freedom of press, freedom of religion, the right to go to court, have a lawyer, and some others.

Over the past 200 years 26 amendments have been adopted ___ (F). It provides the basis for political stability, individual freedom, economic growth and social progress.

1. which are given to a Federal government

2. because it did not guarantee basic freedoms and individual rights

3. but the Constitution itself has not been changed

4. so it has to be changed

5. which a nation or a state is constituted and governed

6. which were called the Bill of Rights

7. that there would be a need for altering it

Решение:

Пропуску A соответствует часть текста под номером 5.

Пропуску B соответствует часть текста под номером 1.

Пропуску C соответствует часть текста под номером 7.

Пропуску D соответствует часть текста под номером 2.

Пропуску E соответствует часть текста под номером 6.

Пропуску F соответствует часть текста под номером 3.

Показать ответ

Источник: ЕГЭ-2018, английский язык: 30 тренировочных вариантов для подготовки к ЕГЭ. Е. С. Музланова

Сообщить об ошибке

Тест с похожими заданиями

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed.[1] These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is. When these principles are written down into a single or set of legal documents, those documents may be said to comprise a written constitution.

Constitutions concern different levels of organizations, from sovereign states to companies and unincorporated associations. A treaty which establishes an international organization is also its constitution in that it would define how that organization is constituted. Within states, whether sovereign or federated, a constitution defines the principles upon which the state is based, the procedure in which laws are made and by whom. Some constitutions, especially written constitutions, also act as limiters of state power by establishing lines which a state’s rulers cannot cross such as fundamental rights.

The Constitution of India is the longest written constitution of any sovereign country in the world,[2] containing 444 articles,[3] 12 schedules and 94 amendments, with 117,369 words in its English language version,[4] while the United States Constitution is the shortest written constitution, at 7 articles and 27 amendments.[5]

Etymology

The term constitution comes through French from the Latin word constitutio, used for regulations and orders, such as the imperial enactments (constitutiones principis: edicta, mandata, decreta, rescripta).[6] Later, the term was widely used in canon law for an important determination, especially a decree issued by the Pope, now referred to as an apostolic constitution.

General features

Generally, every modern written constitution confers specific powers to an organization or institutional entity, established upon the primary condition that it abides by the said constitution’s limitations. According to Scott Gordon, a political organization is constitutional to the extent that it «contain[s] institutionalized mechanisms of power control for the protection of the interests and liberties of the citizenry, including those that may be in the minority.»[7]

The Latin term ultra vires describes activities of officials within an organization or polity that fall outside the constitutional or statutory authority of those officials. For example, a students’ union may be prohibited as an organization from engaging in activities not concerning students; if the union becomes involved in non-student activities these activities are considered ultra vires of the union’s charter, and nobody would be compelled by the charter to follow them. An example from the constitutional law of sovereign states would be a provincial government in a federal state trying to legislate in an area exclusively enumerated to the federal government in the constitution, such as ratifying a treaty. Ultra vires gives a legal justification for the forced cessation of such action, which might be enforced by the people with the support of a decision of the judiciary, in a case of judicial review. A violation of rights by an official would be ultra vires because a (constitutional) right is a restriction on the powers of government, and therefore that official would be exercising powers he doesn’t have.

In most but not all modern states the constitution has supremacy over ordinary statute law (see Uncodified constitution below); in such states when an official act is unconstitutional, i.e. it is not a power granted to the government by the constitution, that act is null and void, and the nullification is ab initio, that is, from inception, not from the date of the finding. It was never «law», even though, if it had been a statute or statutory provision, it might have been adopted according to the procedures for adopting legislation. Sometimes the problem is not that a statute is unconstitutional, but the application of it is, on a particular occasion, and a court may decide that while there are ways it could be applied that are constitutional, that instance was not allowed or legitimate. In such a case, only the application may be ruled unconstitutional. Historically, the remedy for such violations have been petitions for common law writs, such as quo warranto.

History and development

Early constitutions

Excavations in modern-day Iraq by Ernest de Sarzec in 1877 found evidence of the earliest known code of justice, issued by the Sumerian king Urukagina of Lagash ca 2300 BC. Perhaps the earliest prototype for a law of government, this document itself has not yet been discovered; however it is known that it allowed some rights to his citizens. For example, it is known that it relieved tax for widows and orphans, and protected the poor from the usury of the rich.

After that, many governments ruled by special codes of written laws. The oldest such document still known to exist seems to be the Code of Ur-Nammu of Ur (ca 2050 BC). Some of the better-known ancient law codes include the code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin, the code of Hammurabi of Babylonia, the Hittite code, the Assyrian code and Mosaic law.

Later constitutions

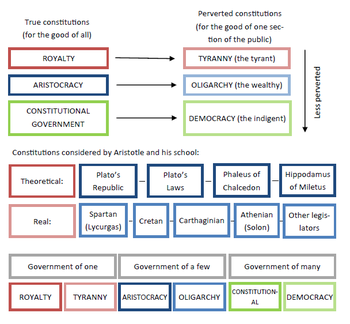

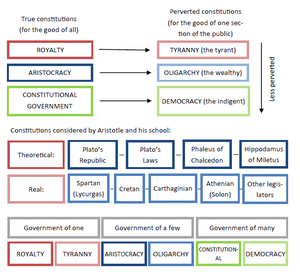

Diagram illustrating the classification of constitutions by Aristotle.

Athens

In 621 BC a scribe named Draco codified the cruel oral laws of the city-state of Athens; this code prescribed the death penalty for many offences (nowadays very severe rules are often called «Draconian»). In 594 BC Solon, the ruler of Athens, created the new Solonian Constitution. It eased the burden of the workers, and determined that membership of the ruling class was to be based on wealth (plutocracy), rather than by birth (aristocracy). Cleisthenes again reformed the Athenian constitution and set it on a democratic footing in 508 BC.

Aristotle (ca 350 BC) was one of the first in recorded history to make a formal distinction between ordinary law and constitutional law, establishing ideas of constitution and constitutionalism, and attempting to classify different forms of constitutional government. The most basic definition he used to describe a constitution in general terms was «the arrangement of the offices in a state». In his works Constitution of Athens, Politics, and Nicomachean Ethics he explores different constitutions of his day, including those of Athens, Sparta, and Carthage. He classified both what he regarded as good and what he regarded as bad constitutions, and came to the conclusion that the best constitution was a mixed system, including monarchic, aristocratic, and democratic elements. He also distinguished between citizens, who had the right to participate in the state, and non-citizens and slaves, who did not.

Rome

The Romans first codified their constitution in 450 BC as the Twelve Tables. They operated under a series of laws that were added from time to time, but Roman law was never reorganised into a single code until the Codex Theodosianus (AD 438); later, in the Eastern Empire the Codex repetitæ prælectionis (534) was highly influential throughout Europe. This was followed in the east by the Ecloga of Leo III the Isaurian (740) and the Basilica of Basil I (878).

India

The Edicts of Ashoka established constitutional principles for the 3rd century BC Maurya king’s rule in Ancient India.

Germania

Many of the Germanic peoples that filled the power vacuum left by the Western Roman Empire in the Early Middle Ages codified their laws. One of the first of these Germanic law codes to be written was the Visigothic Code of Euric (471). This was followed by the Lex Burgundionum, applying separate codes for Germans and for Romans; the Pactus Alamannorum; and the Salic Law of the Franks, all written soon after 500. In 506, the Breviarum or «Lex Romana» of Alaric II, king of the Visigoths, adopted and consolidated the Codex Theodosianus together with assorted earlier Roman laws. Systems that appeared somewhat later include the Edictum Rothari of the Lombards (643), the Lex Visigothorum (654), the Lex Alamannorum (730) and the Lex Frisionum (ca 785). These continental codes were all composed in Latin, whilst Anglo-Saxon was used for those of England, beginning with the Code of Ethelbert of Kent (602). In ca. 893, Alfred the Great combined this and two other earlier Saxon codes, with various Mosaic and Christian precepts, to produce the Doom Book code of laws for England.

Japan

Japan’s Seventeen-article constitution written in 604, reportedly by Prince Shōtoku, is an early example of a constitution in Asian political history. Influenced by Buddhist teachings, the document focuses more on social morality than institutions of government per se and remains a notable early attempt at a government constitution.

Medina

The Constitution of Medina (Arabic: صحیفة المدینه, Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīna), also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib (later known as Medina), including Muslims, Jews, and pagans.[8][9] The document was drawn up with the explicit concern of bringing to an end the bitter inter tribal fighting between the clans of the Aws (Aus) and Khazraj within Medina. To this effect it instituted a number of rights and responsibilities for the Muslim, Jewish, and pagan communities of Medina bringing them within the fold of one community—the Ummah.[10]

The precise dating of the Constitution of Medina remains debated but generally scholars agree it was written shortly after the Hijra (622).[11] It effectively established the first Islamic state. The Constitution established: the security of the community, religious freedoms, the role of Medina as a haram or sacred place (barring all violence and weapons), the security of women, stable tribal relations within Medina, a tax system for supporting the community in time of conflict, parameters for exogenous political alliances, a system for granting protection of individuals, a judicial system for resolving disputes, and also regulated the paying of Blood money (the payment between families or tribes for the slaying of an individual in lieu of lex talionis).

Wales

In Wales, the Cyfraith Hywel was codified by Hywel Dda c. 942–950.

Rus

The Pravda Yaroslava, originally combined by Yaroslav the Wise the Grand Prince of Kiev, was granted to Great Novgorod around 1017, and in 1054 was incorporated into the Russkaya Pravda, that became the law for all of Kievan Rus. It survived only in later editions of the 15th century.

Iroquois

The Gayanashagowa, the oral constitution of the Iroquois nation also known as the Great Law of Peace, established a system of governance in which sachems (tribal chiefs) of the members of the Iroquois League made decisions on the basis of universal consensus of all chiefs following discussions that were initiated by a single tribe. The position of sachem descended through families, and were allocated by senior female relatives.[12]

Historians including Donald Grindle,[13] Bruce Johansen[14] and others[15] believe that the Iroquois constitution provided inspiration for the United States Constitution and in 1988 was recognised by a resolution in Congress.[16] The thesis is not considered credible.[12][17] Stanford University historian Jack N. Rakove stated that «The voluminous records we have for the constitutional debates of the late 1780s contain no significant references to the Iroquois» and stated that there are ample European precedents to the democratic institutions of the United States.[18] Francis Jennings noted that the statement made by Benjamin Franklin frequently quoted by proponents of the thesis does not support for this idea as it is advocating for a union against these «ignorant savages» and called the idea «absurd».[19] Anthropologist Dean Snow stated that though Franklin’s Albany Plan may have drawn some inspiration from the Iroquois League, there is little evidence that either the Plan or the Constitution drew substantially from this source and argues that «…such claims muddle and denigrate the subtle and remarkable features of Iroquois government. The two forms of government are distinctive and individually remarkable in conception.»[20]

England

In England, Henry I’s proclamation of the Charter of Liberties in 1100 bound the king for the first time in his treatment of the clergy and the nobility. This idea was extended and refined by the English barony when they forced King John to sign Magna Carta in 1215. The most important single article of the Magna Carta, related to «habeas corpus«, provided that the king was not permitted to imprison, outlaw, exile or kill anyone at a whim—there must be due process of law first. This article, Article 39, of the Magna Carta read:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

This provision became the cornerstone of English liberty after that point. The social contract in the original case was between the king and the nobility, but was gradually extended to all of the people. It led to the system of Constitutional Monarchy, with further reforms shifting the balance of power from the monarchy and nobility to the House of Commons.

Serbia

The Nomocanon of Saint Sava (Serbian: Zakonopravilo)[21][22][23] was the first Serbian constitution from 1219. This legal act was well developed. St. Sava’s Nomocanon was the compilation of Civil law, based on Roman Law and Canon law, based on Ecumenical Councils and its basic purpose was to organize functioning of the young Serbian kingdom and the Serbian church. Saint Sava began the work on the Serbian Nomocanon in 1208 while being at Mount Athos, using The Nomocanon in Fourteen Titles, Synopsis of Stefan the Efesian, Nomocanon of John Scholasticus, Ecumenical Councils’ documents, which he modified with the canonical commentaries of Aristinos and John Zonaras, local church meetings, rules of the Holy Fathers, the law of Moses, translation of Prohiron and the Byzantine emperors’ Novellae (most were taken from Justinian’s Novellae). The Nomocanon was completely new compilation of civil and canonical regulations, taken from the Byzantine sources, but completed and reformed by St. Sava to function properly in Serbia. Beside decrees that organized the life of church, there are various norms regarding civil life, most of them were taken from Prohiron. Legal transplants of Roman-Byzantine law became the basis of the Serbian medieval law. The essence of Zakonopravilo was based on Corpus Iuris Civilis.

Stefan Dušan, Emperor of Serbs and Greeks, enacted Dušan’s Code (Serbian: Dušanov Zakonik)[24] in Serbia, in two state congresses: in 1349 in Skopje and in 1354 in Serres. It regulated all social spheres, so it was the second Serbian constitution, after St. Sava’s Nomocanon (Zakonopravilo). The Code was based on Roman-Byzantine law. The legal transplanting is notable with the articles 171 and 172 of Dušan’s Code, which regulated the juridical independence. They were taken from the Byzantine code Basilika (book VII, 1, 16-17).

Hungary

In 1222, Hungarian King Andrew II issued the Golden Bull of 1222.

Saxony

Between 1220 and 1230, a Saxon administrator, Eike von Repgow, composed the Sachsenspiegel, which became the supreme law used in parts of Germany as late as 1900.

Mali Empire

In 1236, Sundiata Keita presented an oral constitution federating the Mali Empire, called the Kouroukan Fouga.

Ethiopia

Meanwhile, around 1240, the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer, ‘Abul Fada’il Ibn al-‘Assal, wrote the Fetha Negest in Arabic. ‘Ibn al-Assal took his laws partly from apostolic writings and Mosaic law, and partly from the former Byzantine codes. There are a few historical records claiming that this law code was translated into Ge’ez and entered Ethiopia around 1450 in the reign of Zara Yaqob. Even so, its first recorded use in the function of a constitution (supreme law of the land) is with Sarsa Dengel beginning in 1563. The Fetha Negest remained the supreme law in Ethiopia until 1931, when a modern-style Constitution was first granted by Emperor Haile Selassie I.

China

In China, the Hongwu Emperor created and refined a document he called Ancestral Injunctions (first published in 1375, revised twice more before his death in 1398). These rules served in a very real sense as a constitution for the Ming Dynasty for the next 250 years.

Sardinia

In 1392 the Carta de Logu was legal code of the Giudicato of Arborea promulgated by the giudicessa Eleanor. It was in force in Sardinia until it was superseded by the code of Charles Felix in April 1827. The Carta was a work of great importance in Sardinian history. It was an organic, coherent, and systematic work of legislation encompassing the civil and penal law.

Modern constitutions

The earliest written constitution still governing a sovereign nation today may be that of San Marino. The Leges Statutae Republicae Sancti Marini was written in Latin and consists of six books. The first book, with 62 articles, establishes councils, courts, various executive officers and the powers assigned to them. The remaining books cover criminal and civil law, judicial procedures and remedies. Written in 1600, the document was based upon the Statuti Comunali (Town Statute) of 1300, itself influenced by the Codex Justinianus, and it remains in force today.

In 1639, the Colony of Connecticut adopted the Fundamental Orders, which is considered the first North American constitution, and is the basis for every new Connecticut constitution since, and is also the reason for Connecticut’s nickname, «the Constitution State». England had two short-lived written Constitutions during Cromwellian rule, known as the Instrument of Government (1653), and Humble Petition and Advice (1657).

Agreements and Constitutions of Laws and Freedoms of the Zaporizian Host can be acknowledged as the first European constitution in a modern sense.[25] It was written in 1710 by Pylyp Orlyk, hetman of the Zaporozhian Host. This «Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk» (as it is widely known) was written to establish a free Zaporozhian-Ukrainian Republic, with the support of Charles XII of Sweden. It is notable in that it established a democratic standard for the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws. This Constitution also limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected Cossack parliament called the General Council. However, Orlyk’s project for an independent Ukrainian State never materialized, and his constitution, written in exile, never went into effect.

Other examples of early European constitutions were the Corsican Constitution of 1755 and the Swedish Constitution of 1772.

All of the British colonies in North America that were to become the 13 original United States, adopted their own constitutions in 1776 and 1777, during the American Revolution (and before the later Articles of Confederation and United States Constitution), with the exceptions of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts adopted its Constitution in 1780, the oldest still-functioning constitution of any U.S. state; while Connecticut and Rhode Island officially continued to operate under their old colonial charters, until they adopted their first state constitutions in 1818 and 1843, respectively.

Enlightenment constitutions

What is sometimes called the «enlightened constitution» model was developed by philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment such as Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke. The model proposed that constitutional governments should be stable, adaptable, accountable, open and should represent the people (i.e. support democracy).[26]

The United States Constitution, ratified June 21, 1788, was influenced by the British constitutional system and the political system of the United Provinces, plus the writings of Polybius, Locke, Montesquieu, and others. The document became a benchmark for republicanism and codified constitutions written thereafter.

Next were the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Constitution of May 3, 1791,[27][28][29] and the French Constitution of September 3, 1791.

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 served as a model for other liberal constitutions of several South-European and Latin American nations like Portuguese Constitution of 1822, constitutions of various Italian states during Carbonari revolts (i.e. in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), or Mexican Constitution of 1824.[30] As a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the absolute monarchy of Denmark lost its personal possession of Norway to another absolute monarchy, Sweden. However the Norwegians managed to infuse a radically democratic and liberal constitution in 1814, adopting many facets from the American constitution and the revolutionary French ones; but maintaining a hereditary monarch limited by the constitution, like the Spanish one. The Serbian revolution initially led to a proclamation of a proto-constitution in 1811; the full-fledged Constitution of Serbia followed few decades later, in 1835.

Principles of constitutional design

After tribal people first began to live in cities and establish nations, many of these functioned according to unwritten customs, while some developed autocratic, even tyrannical monarchs, who ruled by decree, or mere personal whim. Such rule led some thinkers to take the position that what mattered was not the design of governmental institutions and operations, as much as the character of the rulers. This view can be seen in Plato, who called for rule by «philosopher-kings.»[31] Later writers, such as Aristotle, Cicero and Plutarch, would examine designs for government from a legal and historical standpoint.

The Renaissance brought a series of political philosophers who wrote implied criticisms of the practices of monarchs and sought to identify principles of constitutional design that would be likely to yield more effective and just governance from their viewpoints. This began with revival of the Roman law of nations concept[32] and its application to the relations among nations, and they sought to establish customary «laws of war and peace»[33] to ameliorate wars and make them less likely. This led to considerations of what authority monarchs or other officials have and don’t have, from where that authority derives, and the remedies for the abuse of such authority.[34]

A seminal juncture in this line of discourse arose in England from the Civil War, the Cromwellian Protectorate, the writings of Thomas Hobbes, Samuel Rutherford, the Levellers, John Milton, and James Harrington, leading to the debate between Robert Filmer, arguing for the divine right of monarchs, on the one side, and on the other, Henry Neville, James Tyrrell, Algernon Sidney, and John Locke. What arose from the latter was a concept of government being erected on the foundations of first, a state of nature governed by natural laws, then a state of society, established by a social contract or compact, which bring underlying natural or social laws, before governments are formally established on them as foundations.

Along the way several writers examined how the design of government was important, even if the government were headed by a monarch. They also classified various historical examples of governmental designs, typically into democracies, aristocracies, or monarchies, and considered how just and effective each tended to be and why, and how the advantages of each might be obtained by combining elements of each into a more complex design that balanced competing tendencies. Some, such as Montesquieu, also examined how the functions of government, such as legislative, executive, and judicial, might appropriately be separated into branches. The prevailing theme among these writers was that the design of constitutions is not completely arbitrary or a matter of taste. They generally held that there are underlying principles of design that constrain all constitutions for every polity or organization. Each built on the ideas of those before concerning what those principles might be.

The later writings of Orestes Brownson[35] would try to explain what constitutional designers were trying to do. According to Brownson there are, in a sense, three «constitutions» involved: The first the constitution of nature that includes all of what was called «natural law.» The second is the constitution of society, an unwritten and commonly understood set of rules for the society formed by a social contract before it establishes a government, by which it establishes the third, a constitution of government. The second would include such elements as the making of decisions by public conventions called by public notice and conducted by established rules of procedure. Each constitution must be consistent with, and derive its authority from, the ones before it, as well as from a historical act of society formation or constitutional ratification. Brownson argued that a state is a society with effective dominion over a well-defined territory, that consent to a well-designed constitution of government arises from presence on that territory, and that it is possible for provisions of a written constitution of government to be «unconstitutional» if they are inconsistent with the constitutions of nature or society. Brownson argued that it is not ratification alone that makes a written constitution of government legitimate, but that it must also be competently designed and applied.

Other writers[36] have argued that such considerations apply not only to all national constitutions of government, but also to the constitutions of private organizations, that it is not an accident that the constitutions that tend to satisfy their members contain certain elements, as a minimum, or that their provisions tend to become very similar as they are amended after experience with their use. Provisions that give rise to certain kinds of questions are seen to need additional provisions for how to resolve those questions, and provisions that offer no course of action may best be omitted and left to policy decisions. Provisions that conflict with what Brownson and others can discern are the underlying «constitutions» of nature and society tend to be difficult or impossible to execute, or to lead to unresolvable disputes.

Constitutional design has been treated as a kind of metagame in which play consists of finding the best design and provisions for a written constitution that will be the rules for the game of government, and that will be most likely to optimize a balance of the utilities of justice, liberty, and security. An example is the metagame Nomic.[37]

Governmental constitutions

Most commonly, the term constitution refers to a set of rules and principles that define the nature and extent of government. Most constitutions seek to regulate the relationship between institutions of the state, in a basic sense the relationship between the executive, legislature and the judiciary, but also the relationship of institutions within those branches. For example, executive branches can be divided into a head of government, government departments/ministries, executive agencies and a civil service/bureaucracy. Most constitutions also attempt to define the relationship between individuals and the state, and to establish the broad rights of individual citizens. It is thus the most basic law of a territory from which all the other laws and rules are hierarchically derived; in some territories it is in fact called «Basic Law».

Key features

The following are features of democratic constitutions that have been identified by political scientists to exist, in one form or another, in virtually all national constitutions.

Codification

A fundamental classification is codification or lack of codification. A codified constitution is one that is contained in a single document, which is the single source of constitutional law in a state. An uncodified constitution is one that is not contained in a single document, consisting of several different sources, which may be written or unwritten.

Codified constitution

Most states in the world have codified constitutions.

Codified constitutions are often the product of some dramatic political change, such as a revolution. The process by which a country adopts a constitution is closely tied to the historical and political context driving this fundamental change. The legitimacy (and often the longevity) of codified constitutions has often been tied to the process by which they are initially adopted.

States that have codified constitutions normally give the constitution supremacy over ordinary statute law. That is, if there is any conflict between a legal statute and the codified constitution, all or part of the statute can be declared ultra vires by a court, and struck down as unconstitutional. In addition, exceptional procedures are often required to amend a constitution. These procedures may include: convocation of a special constituent assembly or constitutional convention, requiring a supermajority of legislators’ votes, the consent of regional legislatures, a referendum process, and other procedures that make amending a constitution more difficult than passing a simple law.

Constitutions may also provide that their most basic principles can never be abolished, even by amendment. In case a formally valid amendment of a constitution infringes these principles protected against any amendment, it may constitute a so-called unconstitutional constitutional law.