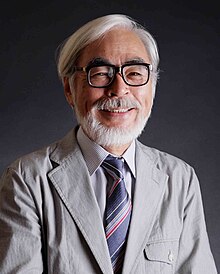

Hayao Miyazaki (japanisch 宮崎 駿 Miyazaki Hayao, * 5. Januar 1941 in Tokio) ist ein japanischer Anime-Regisseur, Drehbuchautor, Zeichner, Grafiker, Mangaka und Filmproduzent. Das von ihm und Isao Takahata 1985 gegründete Studio Ghibli ist weltweit bekannt und Karrieresprungbrett für einige andere Anime-Künstler. Im Jahr 2003 wurde ihm für seinen Film Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland der Oscar verliehen; seine Filme Das wandelnde Schloss (2004) und Wie der Wind sich hebt (2013) waren für den Oscar nominiert.

Biografie[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Unweit des Studio Ghiblis in Koganei befindet sich seit 1998 Miyazakis privates Atelier Butaya (豚屋; dt. etwa „Schweinehaus“)

Hayao Miyazaki wurde am 5. Januar 1941 als zweites Kind des Flugzeugunternehmers Katsuji Miyazaki (1915–1993) in Tokio geboren. Um den US-amerikanischen Bombardements zu entgehen, zog seine Familie in die Stadt Utsunomiya, 100 km nördlich von Tokio, wo er aufwuchs. Nach seiner Schulzeit studierte er zunächst vier Jahre Politikwissenschaften und Ökonomie, bevor er sich 1963 der Produktionsfirma Studio Toei anschloss. Dort begann er seine Karriere als Zeichner diverser Animationsfilme/-Serien, u. a. arbeitete er bei der Fernsehumsetzung der Zeichentrickserie Heidi (1974) mit. Bei Toei lernte er seinen späteren Geschäftspartner Isao Takahata kennen, mit dem er nach mehreren Studiowechseln die Ghibli-Studios gründete.

1979 realisierte Hayao Miyazaki mit Das Schloss des Cagliostro seinen ersten Spielfilm als Autorenfilmer. 1982 startete er sein bis dahin größtes Projekt mit dem Manga Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde, einer Geschichte, in dem eine junge Prinzessin in einer unwirtlichen Welt ums Überleben kämpft. Er avancierte, wie die zwei Jahre später erfolgte Leinwandadaption Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde, zu einem kommerziellen Erfolg und verschaffte ihm internationale Anerkennung. Dies ermöglichte ihm die Gründung von Studio Ghibli, in dem er fortan seine Filme produzierte, das aber auch Filme anderer talentierter Künstler veröffentlichte. Neben Kurzfilmen produzierte er sieben Spielfilmprojekte für die Ghibli-Studios, die ihn zu einem der wichtigsten Vertreter des japanischen Animationsfilms werden ließen.

Nach der Produktion von Prinzessin Mononoke als damals erfolgreichster japanischer Film aller Zeiten 1997 erklärte Miyazaki zunächst seinen Rücktritt als Regisseur, um jüngeren Talenten Platz zu machen. Er kehrte jedoch zurück und schuf unter anderem 2001 den Film Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland, der neue Verkaufsrekorde aufstellte und zum weltweit meistausgezeichneten Zeichentrickfilm wurde (u. a. Goldener Bär 2002, Oscar 2003).

Miyazakis nächster Film, Das wandelnde Schloss, kam 2004 in die Kinos und wurde ebenfalls mehrfach ausgezeichnet; im deutschsprachigen Raum lief eine synchronisierte Fassung im August 2005 an. Das nächste Projekt war der Film Ponyo – Das große Abenteuer am Meer, der im Juli 2008 in die japanischen Kinos kam und bereits am Startwochenende über 1,2 Millionen Besucher zählte.[1] 2008 erhielt der Film eine Einladung in den Wettbewerb der 65. Filmfestspiele von Venedig.[2] Am 1. September 2013 wurde anlässlich der Aufführung seines jüngsten Films Wie der Wind sich hebt bei den 70. Filmfestspielen von Venedig bekannt gegeben, dass Miyazaki in den Ruhestand gehe.[3][4] Im Oktober 2016 vermehrten sich die Gerüchte darüber, dass Miyazaki trotzdem einen neuen Animationsfilm in Spielfilmlänge plane.[5] Im Oktober 2017 bestätigte er diese Gerüchte und gab bekannt, dass dieser Spielfilm anlehnend an das 1937 erschienene Kinderbuch Kimitachi Wa Dō Ikiruka (君たちはどう生きるか; dt. etwa „Wie werdet ihr leben?“) von Genzaburō Yoshino (1899–1981) denselben Titel wie das Buch tragen wird und die Produktionszeit auf drei bis vier Jahre angesetzt sei. Im Dezember des Jahres erklärte Toshio Suzuki zusätzlich, dass die Handlung des Films erheblich von der des Romans abweichen und es sich um einen Fantasy- und Actionfilm handeln werde.[6]

Hayao Miyazaki ist seit 1965 mit der Animatorin Akemi Ōta verheiratet und hat mit ihr zwei Söhne, Gorō und Keisuke.

Wiederkehrende Themen und Motive[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Miyazakis Werke weisen eine Reihe von wiederkehrenden Themen und Motive auf. So bestimmen die komplexen und eigenständigen Mädchen- und Frauencharaktere alle seine Werke[7]. Die Darstellung von Frauen in Miyazakis Filmen weicht auffällig von der in anderen animierten Filmen – sowohl japanischen als auch internationalen – ab[8]. Seine Heldinnen bedienen die gesamte Bandbreite menschlicher Persönlichkeit und nehmen zumeist die Hauptrolle ein (z. B. in Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde, Mein Nachbar Totoro, Kikis kleiner Lieferservice, Prinzessin Mononoke, Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland, Ponyo – Das große Abenteuer am Meer und Arrietty – Die wundersame Welt der Borger). Sie übernehmen körperlich überlegene Führungsrollen ein wie Nausicaä als Regentin ihres Volkes in einer unwirtlichen Welt oder das Wolfsmädchen San in Prinzessin Mononoke, welche die Zuschauer kennenlernen, als sie blutbeschmiert eine Gewehrkugel aus der Schulter eines ihrer Gefährten, eines überdimensionierten Wolfsdämons, saugt. Auch übernehmen Frauen häufig traditionelle Männerberufe, so wie die 17-jährige Fio in Porco Rosso, die als geniale Flugzeugkonstrukteurin in einem fiktiven Italien zur Zeit der Depression zwischen den beiden Weltkriegen ihre Familie wirtschaftlich rettet und später die Flugzeugfabrik übernimmt. Auch die oft ambivalent gezeichneten Antagonisten der Geschichten werden auffällig oft von Frauencharakteren besetzt. In Prinzessin Mononoke wird die naturzerstörende Eisenhütte als aggressiver Gegenpol zu Sans Welt der Naturdämonen von Lady Eboshi geleitet. Die ausschließlich weiblichen Arbeiterinnen der Eisenhütte sind ehemalige Prostituierte, die in der ultraharten Arbeit der Eisenhütte eine Befreiung und Erlösung von ihrem vorherigen Dasein als Prostituierte finden. In Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde wird die gegnerische Nation, mit der sich Nausicaäs Volk im Krieg befindet, von einer harten und unerbittlichen einarmigen Königin geführt. Die Bandbreite der weiblichen Rollen beschränkt sich dennoch nicht auf traditionell männliche Rollenbilder. Auch eher dem traditionellen Frauenbild entsprechende Heldinnen haben ihren Raum und treten in dieser Form oft als Retterinnen auf. So wie die sanfte und bescheidene Sophie, die als Putzfrau in Das wandelnde Schloss den begabten wie eitlen Zauberer und Schlossherrn Howl von seinen inneren wie äußeren Dämonen befreit. Bemerkenswerterweise entwickelt sich die romantische Liebe der beiden, als Sophie in ihrem Alter Ego als ergraute und gekrümmt gehende Großmutter gefangen ist und nicht als die schöne, junge Frau, die sie eigentlich ist. So spielt Miyazaki konstant mit den klassischen Geschlechterrollen und Stereotypen und erlaubt so seinen weiblichen wie männlichen Charakteren die gesamte Bandbreite des menschlichen Daseins. Mit dieser insbesondere für animierte Filme völlig untypischen Darstellung eigenständiger Heldinnen gilt Miyazaki als Vorreiter, der den Weg für eigenständige Disney-Heldinnen wie Brave oder Elsa in Die Eiskönigin oder auch Pixars Alles steht Kopf bereitet hat[9].

Ein weiteres Thema in Miyazakis Filmen ist die Konfrontation von traditioneller Kultur auf der einen Seite, technisierter Moderne und Naturzerstörung auf der anderen Seite.[10] 1997 erklärte Miyazaki in einem Interview: „Ich bin an einen Punkt gelangt, an dem ich einfach keinen Film mehr machen kann, ohne das Problem der Menschheit als Teil eines Ökosystems anzusprechen.“[11] Miyazaki hat für die Darstellung dieser Thematik sowohl japanische (Prinzessin Mononoke, Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland) wie europäische Settings als Hintergrund gewählt (Das Schloss im Himmel, Porco Rosso). Der Film Das wandelnde Schloss (2004) spielt beispielsweise in einer romantischen deutschen oder elsässischen Fachwerkstadt im Zeitalter der Industrialisierung. Die romantische Kulisse, basierend auf Colmar, wird zerstört, als die Stadt einem Bombenangriff aus der Luft zum Opfer fällt.[12] Die drastischen Bilder der brennenden Stadt stellen die Leistungen der Moderne (Industrialisierung, Nationalismus und Militarismus) in Frage. Eine ähnliche Thematik spielt in Prinzessin Mononoke eine tragende Rolle. Hier fällt ein von mythischen Tieren bewohnter Wald dem Holz- bzw. Holzkohlebedarf einer Eisenhütte zum Opfer. Die Technik der Moderne wird mit mythischen oder magischen Gestalten und Kräften aus der traditionellen Überlieferung konfrontiert.[13] Häufig wächst Kindern oder jungen Erwachsenen als Helden von Miyazakis Filmen eine vermittelnde Funktion zwischen diesen Polen zu.[14]

Ein wiederholt auftauchendes Motiv in Miyazakis Filmen sind phantastische Flugmaschinen und Luftschiffe.[15] Die Heldinnen und Helden treibt oft eine tiefe Faszination für das Fliegen an und für Maschinen, die den Traum vom Fliegen wahr werden lassen. Dies reicht von Filmen, in denen es explizit um das Fliegen und den Flugmaschinenbau geht wie z. B. Porco Rosso oder Wie der Wind sich hebt. In anderen Filmen wie Das Schloss im Himmel oder Kikis kleiner Lieferservice ist das Fliegen ein zentrales Element der Geschichte.

Vorbilder und Einflüsse[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Frühe Erinnerungen aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg finden sich in Miyazakis Werk: die nachts von Brandbomben verursachten Feuer finden sich in Nausicaä, ein Haus, aus dem die Familie flüchtete, in Mein Nachbar Totoro und Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland. Miyazakis erste Vorbilder waren mit Osamu Tezuka, Yamakawa Sōji und Fukushima Tetsuji Mangaka, entsprechend wollte er diesen Beruf noch vor dem als Animator ergreifen. Sein Frühwerk, noch als Amateur gezeichnete Comics, war stark von Tezukas Stil geprägt, doch er vernichtete es, um sich davon zu lösen. Yamakawas Shōnen Oja und Fukushimas Sabaku no Maō prägten ihn aber längerfristig. Später beeinflusste ihn auch der französische Comickünstler Jean Giraud alias Mœbius.[16]

Unter den von Miyazaki besonders geschätzten Animationskünstlern finden sich Juri Norstein, Taiji Yabushita und Kazuhiko Okabe. Erzählung einer weißen Schlange, eine Kollaboration der beiden letztgenannten, bezeichnete er als jenen Film, aufgrund dessen er sich entschloss, sich als Animator zu versuchen. Erzählerisch verehrt er unter anderen Lewis Carroll, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Ursula K. Le Guin und Pjotr Pawlowitsch Jerschow. Zeichnerisch übten auch die Illustrationen aus Andrew Langs Märchensammlungen sowie der russische Maler Isaak Lewitan Einfluss auf ihn, letzterer konkret, was die Wolken und Lichtverhältnisse in Wie der Wind sich hebt betrifft. Helen McCarthy sieht zudem Parallelen zur Flämischen Malerei sowie zu Paul Klee.[16]

Miyazaki als Mangazeichner[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Miyazakis erster professioneller Manga war 1969 ein Werbecomic für den Anime-Film Perix der Kater und die drei Mausketiere, an dem er beteiligt war.[16] Dieser erschien in 12 Kapiteln zwischen Januar und März 1969 in den Sonntagsausgaben der Zeitungen Chūnichi Shimbun und Tōkyō Shimbun. Unter dem Pseudonym Saburō Akitsu (秋津三朗) zeichnete er mit Sabaku no Tami (砂漠の民, „das Wüstenvolk“) seine erste eigene Reihe, die in 26 Kapiteln vom 12. September 1969 bis 15. März 1970 in der Shōnen Shōjo Shimbun veröffentlicht wurde, einer der Kommunistischen Partei Japans nahestehenden Jugendzeitung. Anschließend zeichnete er erneut eine Adaption, diesmal zum Film Die Schatzinsel, die in 13 Teilen zwischen Januar und März 1971 in der Chūnichi und Tōkyō Shimbun erschien.[17]

Das wohl bekannteste Werk ist Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde, an dem er von 1982 bis 1994 arbeitete und das auch als Vorlage für den gleichnamigen Anime diente. Seinen Manga Kaze Tachinu, der 2009 in einem Modellbaumagazin veröffentlicht wurde, setzte er 2013 ebenfalls als Anime um.

Filmografie (Auswahl)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Bis in die 1980er Jahre wurden Miyazakis Filme vor allem in den USA und Frankreich stark überarbeitet, wobei die Schnitte und Dialogänderungen teilweise so umfangreich waren, dass die ursprüngliche Handlung völlig entstellt wurde. In der Folge vergab das Studio Ghibli nach Nausicaä zunächst keine Rechte mehr für Veröffentlichungen im Westen.

Erst als Studio Ghibli 1996 einen Distributionsvertrag mit dem Disney-Konzern schloss („Tokuma deal“), bei dem für Kino- und Kaufmarktveröffentlichungen jede Art von Veränderung am ursprünglichen Bildmaterial ausdrücklich ausgeschlossen ist, wurden Miyazakis Filme wieder im Westen veröffentlicht und professionell vermarktet.

Prinzessin Mononoke war der erste Miyazaki-Film, der in Deutschland ungeschnitten in die Kinos kam. Die Distributionsrechte für Deutschland liegen derzeit bei der RTL-Group-Tochtergesellschaft Universum Film GmbH, die sich anschickt, den Rückstau jetzt aufzuarbeiten. So erscheinen seit 2005 im 2-Monats-Rhythmus die Werke des Studio Ghiblis auf DVD. Laputa: Castle in the Sky wurde 20 Jahre nach seiner Veröffentlichung in Japan als Das Schloss im Himmel in die deutschen Kinos gebracht.

Eine Produktion von Studio Ghibli, Die Chroniken von Erdsee (2006), wurde von Miyazakis Sohn Gorō geleitet und entstand ohne Beteiligung von Hayao Miyazaki.

Als Regisseur und Drehbuchautor[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1978: Mirai Shōnen Conan (未来少年コナン Mirai shōnen Konan, engl. Conan, the Boy in Future) – 26-teilige TV-Serie

- 1979: Das Schloss des Cagliostro (ルパン三世 カリオストロの城 Rupan Sansei: Kariosutoro no Shiro) – 110 Minuten

1987 erschien auf Video eine deutsche Fassung mit einer Laufzeit von 84 Minuten als Hardyman räumt auf, 2006 erstmals in Deutschland ungeschnitten auf DVD erschienen - 1980: Shin Lupin Sansei Special (新ルパン三世 SPECIAL Shin Rupan Sansei Special) – 2 Folgen der TV-Serie New Lupin III

- 1984: Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde (風の谷のナウシカ Kaze no Tani no Naushika)

- 1986: Das Schloss im Himmel (天空の城ラピュタ Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta)

- 1988: Mein Nachbar Totoro (となりのトトロ Tonari no Totoro)

- 1989: Kikis kleiner Lieferservice (魔女の宅急便 Majo no Takkyūbin)

- 1992: Porco Rosso (紅の豚 Kurenai no Buta)

- 1997: Prinzessin Mononoke (もののけ姫 Mononoke Hime)

- 2001: Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland (千と千尋の神隠し Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi)

- 2004: Das wandelnde Schloss (ハウルの動く城 Hauru no Ugoku Shiro)

- 2008: Ponyo – Das große Abenteuer am Meer (崖の上のポニョ Gake no Ue no Ponyo)

- 2013: Wie der Wind sich hebt (風立ちぬ Kaze Tachinu)

Als Drehbuchautor[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1972: Die Abenteuer des kleinen Panda (パンダ・コパンダ Panda Kopanda, engl. Panda! Go, Panda!) – 33 Minuten

- 1995: Stimme des Herzens (耳をすませば Mimi o Sumase ba)

- 2010: Arrietty – Die wundersame Welt der Borger (借りぐらしのアリエッティ Karigurashi no Arietti)

- 2011: Der Mohnblumenberg (コクリコ坂から Kokurikozaka kara)

Als Produzent[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1991: Tränen der Erinnerung – Only Yesterday (おもひでぽろぽろ Omoide Poro Poro)

- 2002: Das Königreich der Katzen (猫の恩返し Neko no Ongaeshi)

Regie und Buch für Kurzfilme[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1992: Sora Iro no Tane – TV-Spot, 90 Sekunden, für den japanischen Fernsehsender Nippon TV. Nach einem Kinderbuch von Reiko Nakagawa und Yuriko Omura

- 1992: Nandarou – Serie von fünf TV-Spots, 15 bzw. 5 Sekunden, für Nippon TV. Eine Figur aus den Spots wurde das offizielle Maskottchen des Senders.

- 1995: On Your Mark – Musikvideo für das japanische Pop-Duo Chage and Aska

- 2001: Kujira Tori – Kurzfilm für das Ghibli-Museum

- 2002: Mei to Konekobasu – Kurzfilm für das Ghibli-Museum

- 2002: Kūsō no Sora Tobu Kikaitachi – Kurzfilm für das Ghibli-Museum

- 2006: Mizugumo Monmon – Kurzfilm für das Ghibli-Museum

- 2017: Kemushi no Boro – Kurzfilm für das Ghibli-Museum

Als Zeichner[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1971: Die Schatzinsel (動物宝島 Dōbutsu Takarajima) – 78 min

nach dem Roman von Robert Louis Stevenson, Regie Hiroshi Ikeda

als Key Animator und Story Consultant - 1974: Heidi (アルプスの少女ハイジ Arupusu no Shōjo Haiji) – 52-teilige Fernsehserie – als Scene Designer und Screen Layouter

- 1976: Marco (Haha o Tazunete Sanzenri) – 52-teilige Fernsehserie – als Animator, Scene Designer und Layout Artist

- 1979: Anne mit den roten Haaren (赤毛のアン Akage no An) – 50-teilige Fernsehserie – als Scene Designer und als Layout Artist für die Folgen 1–15

Als Animator[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1969: Perix der Kater und die 3 Mausketiere (BRD-Verleihtitel) bzw. Der gestiefelte Kater (DDR-Verleihtitel) (長靴をはいた猫 Nagagutsu o Haita Neko) – 80 Minuten

nach der französischen Version des Märchens Der gestiefelte Kater von Charles Perrault, Regie Kimio Yabuki

als Key Animator - 1975: Niklaas, ein Junge aus Flandern (Furandāsu no Inu) – 52-teilige Fernsehserie – als Animator für Folge 15

Bibliografie (Auswahl)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1982–1994: Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde

- 2009: Kaze Tachinu

- 2009: Starting Point: 1979–1996 Eine Sammlung von Essays, Interviews, Skizzen und Memoiren.

- 2014: Turning Point: 1997–2008 Eine weitere Sammlung von Essays, Interviews, Skizzen und Memoiren, ISBN 978-1-4215-6090-8.

Internationale Auszeichnungen (Auswahl)[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

| Platz | Film |

|---|---|

| 23 | Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland |

| 69 | Prinzessin Mononoke |

| 141 | Das wandelnde Schloss |

| 149 | Mein Nachbar Totoro |

| 220 | Nausicaä aus dem Tal der Winde |

- 2002: Goldener Bär der Berlinale für Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland (geteilt mit dem irischen Film Bloody Sunday)

- 2003: Oscar für Chihiros Reise ins Zauberland als „Bester Animationsfilm“

- 2005: Aufnahme in die Liste der 100 einflussreichsten Menschen der Welt des TIME Magazine (des Jahres 2005)

- 2006: Oscar-Nominierung für Das wandelnde Schloss als „Bester Animationsfilm“

- 2006: Nebula Award in der Kategorie „Best Script (Bestes Drehbuch)“ für Das wandelnde Schloss (mit Cindy Davis Hewitt und Donald H. Hewitt)

- 2009: Karl Edward Wagner Award im Rahmen der British Fantasy Awards

- 2010: Auszeichnung als bester Animationsfilm im Langfilmwettbewerb AniMovie beim Trickfilmfestival Stuttgart für Ponyo – Das große Abenteuer am Meer

- 2012: Person mit besonderen kulturellen Verdiensten der japanischen Regierung[19]

- 2014: Oscar-Nominierung für Wie der Wind sich hebt als „Bester Animationsfilm“

- 2014: Aufnahme in die Science Fiction Hall of Fame[20]

- 2015: Ehrenoscar für sein Lebenswerk als Regisseur[21]

- 2018: Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award (Lebenswerk)

- 2019: World Fantasy Award für das Lebenswerk

Literatur[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Alessandro Bencivenni: Hayao Miyazaki. Il dio dell’anime. Le Mani, Recco (Genova) 2003, ISBN 88-8012-251-7 (italienisch).

- Dani Cavallaro: The Animé Art of Hayao Miyazaki. McFarland & Co., Jefferson NC u. a. 2006, ISBN 0-7864-2369-2 (englisch).

- Peter M. Gaschler: Noch einmal von vorne anfangen. Hayao Miyazaki, Meister des Anime. In: Sascha Mamczak, Wolfgang Jeschke (Hrsg.): Das Science Fiction Jahr 2009 (= Heyne-Bücher 06, Heyne Science-fiction & Fantasy. Band 52554). Heyne, München 2009, ISBN 978-3-453-52554-2, S. 1025–1039.

- Martin Kölling: Japans Walt Disney. Hayao Miyazaki ist der Oscar-gekrönte Altmeister des Zeichentrickfilms. Doch die digitale Revolution verändert sein Metier dramatisch. In: Handelsblatt, 16. Juli 2015, S. 22–23.

- Helen McCarthy: Hayao Miyazaki. Master of Japanese Animation. Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley CA 1999, ISBN 1-880656-41-8 (Revised edition. ebenda 2002), (englisch).

- Hayao Miyazaki: Starting Point. 1979–1996. 2nd printing. VIZ Media, San Francisco CA 2009, ISBN 978-1-4215-0594-7 (englisch).

- Julia Nieder: Die Filme von Hayao Miyazaki. Schüren Presseverlag, Marburg 2006, ISBN 3-89472-447-1 (deutsch).

Einzelnachweise[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- ↑ Anime News Network über den Erfolg von Gake no ue no Ponyo

- ↑ Nick Vivarelli: Venice Film Festival announces Slate. ‘Burn After Reading,’ ‘Hurt Locker’ top lineup. (Nicht mehr online verfügbar.) Variety, 29. Juli 2008, archiviert vom Original am 18. Juni 2009; abgerufen am 4. August 2014 (englisch).

- ↑ Miyazaki verabschiedet sich vom Film. In: sueddeutsche.de. 2. September 2013, abgerufen am 13. März 2018.

- ↑ asienspiegel.ch

- ↑ Ghibli Producer: «No Greenlight for Miyazaki’s New Feature Film Yet». In: Crunchyroll. 4. März 2017 (crunchyroll.com [abgerufen am 5. März 2017]).

- ↑ Ghibli reveals genre of Hayao Miyazaki’s next anime. In: Japan Today. 2. Dezember 2017, abgerufen am 8. Dezember 2017 (englisch).

- ↑ Gabrielle Bellot: What Hayao Miyazaki’s Films Taught Me About Being a Woman. 19. Oktober 2016, abgerufen am 15. August 2020 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Derrick Recca: Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli: Reimagining the Portrayal of Women in Japanese Anime. (academia.edu [abgerufen am 15. August 2020]).

- ↑ Ella Alex, er: Why Studio Ghibli might just be the most feminist film franchise of all time. 5. Februar 2020, abgerufen am 15. August 2020 (britisches Englisch).

- ↑ Julia Nieder: Die Filme von Hayao Miyazaki. Marburg 2006, S. 121–122. Vgl. auch: Takashi Oshiguchi: Hayao Miyazaki – interviewed by Takashi Oshigichi. (1993). In: Trish Ledoux (Hrsg.): Anime Interviews. The First Five Years of Animerica, Anime & Manga Monthly (1992–1997). Cadence Books, San Francisco CA 1997, ISBN 1-56931-220-6, S. 33. Im gleichen Sinne: Helen McCarthy: Hayao Miyazaki. Master of Japanese Animation. Berkeley 2002, S. 101 ff.

- ↑ Analysis. Digitization Zooms in on Japan’s Film Industry. In: Asia Pulse. 16. Mai 1997, ISSN 0739-0548.

- ↑ Karl R. Kegler: Godzilla trifft Poelzig. Europäische Kulissen, Kopie und Collage im phantastischen Film Japans. In: archimaera. Heft 2, 2009, ISSN 1865-7001.

- ↑ Helen McCarthy: Hayao Miyazaki. Master of Japanese Animation. Berkeley 2002, S. 157 f., S. 199.

- ↑ Julia Nieder: Die Filme von Hayao Miyazaki. Marburg 2006, S. 119–121.

- ↑ Helen McCarthy: Hayao Miyazaki. Master of Japanese Animation. Berkeley 2002, S. 157 f., S. 160.

- ↑ a b c Helen McCarthy: Drawing on the Past. In: Sight & Sound. Volume 24, Nr. 6. BFI, Juni 2014, ISSN 0037-4806, S. 26 f.

- ↑ Comic Box’82年11・12月号 Comic Box’83年2・3月号. (Nicht mehr online verfügbar.) Mandarake, 14. Februar 2008, archiviert vom Original am 26. Juli 2014; abgerufen am 2. Februar 2015 (japanisch). Info: Der Archivlink wurde automatisch eingesetzt und noch nicht geprüft. Bitte prüfe Original- und Archivlink gemäß Anleitung und entferne dann diesen Hinweis.

- ↑ Die Top 250 der IMDb (Stand: 12. Februar 2018)

- ↑ Hayao Miyazaki Receives Japanese Cultural Merit Honor. Anime News Network, 30. Oktober 2012 (englisch)

- ↑ science fiction awards database – Hayao Miyazaki. Abgerufen am 24. November 2017 (englisch).

- ↑ asienspiegel.ch

Literatur[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- S. Noma (Hrsg.): Miyazaki Hayo. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha, 1993. ISBN 4-06-205938-X, S. 990.

Weblinks[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Literatur von und über Hayao Miyazaki im Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

- Hayao Miyazaki in der Internet Movie Database (englisch)

- Miyazaki-Informationen auf Nausicaa.net (englisch)

- Lars-Olav Beier: Fröhliches Weltenzertrümmern. In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 37. 13. September 2010, abgerufen am 27. März 2021.

- 25 Jahre Zusammenarbeit von Joe Hisaishi & Hayao Miyazaki. (Nicht mehr online verfügbar.) AnimeY Online Magazin, archiviert vom Original am 21. Oktober 2009; abgerufen am 4. August 2014.

- Katja Nicodemus: Im Reich des närrischen Kaisers. In: DIE ZEIT Nº 36/2010. 16. September 2010, abgerufen am 27. März 2021.

Сегодня 15.04.2022 19:22 свежие новости час назад

Прогноз на сегодня : Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы . Развитие событий.

Актуально сегодня (15.04.2022 19:22): Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

..

1. Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

9041462618282665b80f0416d63c2cfc d9b5b5eae80a8d70e7f8a902deba94bb

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

Hayao miyazaki and studio ghibli текст егэ ответы

самодельный двухтактный усилитель на г 807 | pmp3770b prestigio firmware | простейшие задачи по электротехнике с решениями | фото голых деревенских баб раком | презентация на тему сказки пушкина 5 класс | ноты летели облака алина орлова фортопиано | sandra orlow early set forum | безопасно 3d хентай | дневники вампира 1 сезон смотреть на русском языке | скачать музыку не бесплатно на телефон короткие на звонок прикольные |

Invision Community © 2022 IPS, Inc.

Карта сайт Rss

s

p

Hayao Miyazaki (宮崎 駿, Miyazaki Hayao, born January 5, 1941, in Tokyo, Japan) is a Japanese director, animator and cartoonist. He adopted several aliases throughout his career, such as Saburo Akitsu (あきつ さぶろう), Tsutomu Teruki (照樹 務 , working at TMS Entertainment) and Miya Iwasaki. He is the co-founder of Studio Ghibli and is the Chairman of the Tokuma Memorial animation Cultural Foundation and Mitaka Municipal Animation Museum of Art (Ghibli Museum). He’s also an active member of the Totoro no Furusato Foundation.

Born in Bunkyō ward of Tokyo, Japan. He studied Political Science and Economics at Gakushuin University and later joined Toei Animation in 1963 as an animator. Following that, he became a freelancer, eventually producing Future Boy Conan and directed his first theatrical animated film The Castle of Cagliostro. In 1984, he, along with Isao Takahata, Toshio Suzuki and Yasuyoshi Tokuma co-founded Studio Ghibli. When Ghibli established its independence from Tokuma Shoten in 2005, he was appointed as Board of Directors.

Since then, he has directed numerous animated films such as My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Howl’s Moving Castle, The Wind Rises and Princess Mononoke and won the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film for Spirited Away. In 2014, he became the second Japanese to win the Academy Honorary Award. He came out of retirement to work on How Do You Live?

He lives in Tokorozawa, Saitama and is a known smoker. He is married to Akemi Miyazaki and two children, Goro Miyazaki and Keisuke Miyazaki. His blood type is O.

He announced his retirement after his last feature film, The Wind Rises.

In 2016, he came out of retirement to work on a new film confirmed to be How Do You Live?.

Character

Hayao Miyazaki is emotional and passionate, has a fiercely undulating human nature, is strongly self-assertive and tends to prompt action, has a bountiful expressiveness and curiosity, and possesses an imagination so vivid it verge on hallucinatory vision. And it goes without saying that all these characteristics are in constant conflict with the self of idealism and justice, the fastidiousness, the self-denial, the self-control and the self-abnegation that have characterized him since his youth.

One might even say that this conflict is what creates his own complicated yet appealing character. In fact, one way people who know Miyazaki forgive some of his statements is by saying, «Well, he is, after all, a bundle of contradictions.» One hiree at Studio Ghibli once said that the secret to getting along with Miya-san was as follows: «You’d better not swallow everything he tells you today as is. Tomorrow he might well tell you the opposite.[1]

History

Early life

Miyazaki was born in Tokyo, and is the second son of four brothers. His father was Katsuji Miyazaki and their family owned Miyazaki Airplane Mfg. Co., Ltd (宮崎航空機製作所 , Miyazaki Kōkūki Seisakusho), and their factory was based in Tochigi Prefecture in Kanuma. When the Second World War began, their family was evacuated to Utsunomiya. It was here that Miyazaki stayed until his third grade of elementary school. He moved to Eifuku, Suginami, Tokyo where he studied until 4th grade of elementary school in 1950.

When he was a child, he described himself as weak and was not good at exercising. Despite his physical deficiencies, he excelled at drawing. He was an avid reader and a big fan of mangakas like Osamu Tezuka and Shigeru Sugiura. He also loved the pictures books of Tetsuji Fukushima, particularly The Devil of the Savage. When he was in third year at Toyotama High School, he grew interested in animation and was greatly influenced by Toei Animation and their film Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958). He taught himself drawing at Fumio Sato’s atelier and was influenced by Impressionist painters like Paul Cézanne.

Working as an Animator

He entered Gakushuin University and joined the Children’s Literature Circle (Children’s Culture Study Group). While helping plan several puppet shows, he continued drawing manga with the goal of becoming a professional manga artist, but decided to move into the world of animation. After graduating from Gakushuin University, he joined Toei Animation as an animator. He struggled with the workmanlike atmosphere of Toei Animation, and never stopped his dream of being a cartoonist. He was greatly enamored by the Soviet-produced feature-length animated film Snow Queen (1957). That film, along with several others pushed Miyazaki to stick with working in animation. Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon (1965) also served as a strong inspiration for the budding young animator. He was promoted to general secretary for the Toei Animation Labor Union, and strove to improve the treatment of animators. In the fall of 1965, he married fellow Toei animator Akemi Ota at the age of 24, and later had two boys, Goro Miyazaki and Keisuke Miyazaki. He later teamed up with Isao Takahata, Yasuo Ōtsuka and Kouji Mori to work on The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun. This early masterpiece took three years (1965-1968) to complete.

In 1971, he left Toei Animation with Isao Takahata and Yoichi Kotabe and transferred to A Production to produce, Pippi Longstocking, but that project was abandoned after failing to obtain permission from the original author. Following that setback, Miyazaki and Takahata were invited by Yasuo Ōtsuka to adapt and direct Monkey Punch’s Lupin the Third Part I (1971). Unfortuntely, the series suffered from a low audience viewership. Despite the broadcast ending after half a year, it served as the blueprint for subsequent spinoffs. Utilizing their experience from the failed Pippi project, Miyazaki, Takahata, Ōtsuka and Kotabe produced Panda! Go Panda and its sequel (1972, 1973). Miyazaki was in charge of screenplay, scene setting, art, original drawing, etc.

Miyazaki then transferred to Zuiyo Eizo (later Nippon Animation) with Takahata and Kotabe, where they produced Heidi, Girl of the Alps in 1974. He was in charge of scene setting and scene composition (layout) for several of the series’ episodes. The series was a big hit and achieved an average audience rating of 26.9%. This was Miyazaki’s first mainstream success.

Future Boy Conan

In 1978, Miyazaki directed Future Boy Conan for NHK. While he was not credited as director in the end credits, Miyazaki’s responsibilities encompassed that of a director. In trying to keep with the strict weekly broadcasting schedule, Miyazaki was not only in charge of directing, but also in storyboarding, setting, character design and mechanical design. He drew most storyboards and layouts, and the script made by the staff. The storyboard, layout, and original drawings were all checked by Isao Takahata. The series received decent viewership at the time, and is considered a classic to this day.

Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro

After the release of Future Boy Conan, Yasuo Ōtsuka approached Miyzaki to direct a new Lupin III movie for Telecom Animation Film (then known as Tokyo Movie Shinsha). Thus in 1979, The Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki’s directorial debut, was born.

Miyazaki threw himself to complete the film in record time. He worked on the film for a brief four and a half months, describing the experience as where he learnt his limitations of his physical strength. Unfortunately, due to the stylistic difference between Lupin the Third Part II and the immense popularity of science fiction animation at the time, the film was a flop at the box office. Thankfully, the film found success after it was rebroadcast on television, and is now considered an animation classic.

Immediately after this, Miyazaki found himself working on script, storyboard, and director on a handful of episodes for the ongoing Lupin III series. He worked on the series finale, which notably featured designs that would later be seen in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. It was around this time when Miyazaki met Toshio Suzuki, who was currently working as deputy editor of Animage magazine.

With the release of the Lupin the Third Part I series, a third Lupin III movie was announced. Miyazaki was once again tapped as director, but he turned the offer down. Miyazaki instead recommended his friend Mamoru Oshii to direct.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Miyazaki, along with Yasuo Ōtsuka and Isao Takahata, were then involved in the US-Japan collaboration Little Nemo by Telecom Animation Film. The trio would fly back and forth to the United States, but shortly after producing a pilot film, Miyazaki and his friends decided to abandon the project. It was at this time when Miyazaki began developing concepts that would later become My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and Castle in the Sky.

Toshio Suzuki, who fell in love with Miyazaki’s talent, brought several of Miyazaki’s proposal and image boards for what would be Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind to Tokuma Shoten (the publisher of Animage) in order to adapt it into a film. However, Yasuyoshi Tokuma (then presiden of Tokuma Shoten) and his fellow executives rejected this as they felt it was unviable as a film if didn’t have an accompanying manga. Hideo Ogata, editor-in-chief of Tokuma Shoten’s Animage, who had been a fan of Miyazaki since producing Future Boy Conan, decided to use the magazine to help publish Nausicaä as a manga. In February 1982, the serialization of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind began, and eventually gained the support of many readers.

In addition, Ogata and Suzuki proposed a special short animated film to help promote Nausicaä. The project’s scope gradually expanded, and thanks to Ogata’s efforts, Yasuyoshi Tokuma became convinced as he was enthusiastic and dreamed of entering the movie business at the time. He decided to produce Nausicaä in an animated film, which was later released in 1984.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind proved to be a big hit, following the success of The Castle of Cagliostro as it was being broadcast on television. The film also helped spur the ecology boom at the time.

Studio Ghibli

Studio Ghibli was established in 1985 thanks to an investment from Tokuma Shoten. Subsequent film productions would also be funded by Tokuma. The initial disappointing box office returns of 1986 release of Castle in the Sky and 1988 My Neighbor Totoro were later offset thanks to the secondary merchandising sales and release on home video.

Additionally, in 1986, after Mamoru Oshii’s Lupin III movie failed to get produced, Oshii was appointed as the director at Studio Ghibli. He then produced Anchor, which was written by Miyazaki. (Anchor would also fail to get produced)[2]

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) was initially supposed to be directed by Sunao Katabuchi, but had to drop out after an issue with the sponsors. Miyazaki then took over directing duties. Kiki was Ghibli’s first major box office hit, and thanks to its success, the studio was able to hire more talent and expand its operations.

Porco Rosso (1992) was originally planned as a 45 minute in-flight film for Japan Airlines, but the concept gradually expanded and it was released as a feature film. Due to the end of production on Takahata’s Only Yesterday (1991), Miyazaki initially managed the production of Porco Rosso independently. The outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars in 1991 affected Miyazaki, prompting a more somber tone for the film.

For Whisper of the Heart (1995), Miyazaki was in charge of screenplay, production, executive producer, layout and original drawing.

Princess Mononoke ,» which was released in 1997, was a record-breaking box office hit in Japan. Mononoke proved to be one of Ghibli’s most expensive productions to date, and the stress of that work prompted Miyazaki to push for an early retirement. He returned to work shortly after.

Spirited Away was released in 2001, and was an even bigger hit in Japan and around the world. It set a new record with 23.5 million viewers, and achieved an astouding box office revenue of 30.8 billion yen. It received the highly coveted Golden Bear Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature in 2003. At the press conference following the completion of the film, Miyazaki once again declared his retirement saying, «It’s impossible to make a feature-length anime movie anymore.»

In 2004, Ghibli released Howl ‘s Moving Castle. It was originally supposed to be directed by Mamoru Hosoda, but Hosada dropped out due to creative differences. On its second day of release, the film counted 1.1 million viewers and the film earned 1.48 billion yen in the box office. Howl’s set the second box office opening of all time in Japan. The film won the Osella Award at the Venice International Film Festival and Best Animation Award from the New York Film Critics Association. It was nominated again for an Academy Award that year. In 2005, Miyazaki received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Award for outstanding world-class filmmakers at the Venice International Film Festival. In 2006, he was selected for the Academy Awards selection committee. Miyazaki was selected twice before this, but declined because he wanted to concentrate on his creative activities.

Tales from Earthsea was released in 2006. Miyazaki worked on the original draft, layout, and original picture.

On July 19, 2008, Ponyo was released. A month after its premiere, its Japanese box office record exceeded 10 billion yen. During the production of Ponyo, Miyazaki stated that this work would the last animated film he could work on physically. However, after the movie was released, Miyazaki was shocked to learn that Howl’s Moving Castle had a number of viewers than Ponyo, and this motivated him to «make another movie».

There was a time when Miyazaki didn’t like to appear in front of the media, but during the creation of Ponyo, he developed a close relationship with NHK, and was featured on their program, Professional Work Style. The documentary of his process was a big hit. In addition, Miyazaki was invited to the Foreign Correspondents’ Association of Japan on November 20, 2008, and enthusiastically argued about the concerns in the animation industry. In 2012, he was selected as a Person of Cultural Merit.

In 2013, he released The Wind Rises. On September 1, the same year, Studio Ghibli president Koji Hoshino announced that Miyazaki would retire from the production of feature films. He has since come out of retirement to produce How Do You Live?.

On May 15, 2018, he attended Isao Takahata’s funeral service and read the opening remarks.

Political and Ideological Stance

Good & Evil

Most of Miyazaki’s films feature some sort of struggle between good and evil. For example, in The Castle of Cagliostro, Clarisse d’Cagliostro struggling to save the European Grand Duchy of Gagliostro after it is invaded by the Count Cagliostro, and in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Nausicaä is struggling to save the Valley of the Wind after it is invaded by the Tolmekians. Also, in Castle in the Sky, Pazu must save Sheeta after she is captured by Muska.

Environment

Several of Miyazaki’s film go into man’s concern for nature. Such as, in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Nausicaä spends a portion of the movie doing research to find a cure for the toxin plaguing their lands. And in Princess Mononoke, San, being raised by wolves, is very angry at men for destroying their forests.

Anti-War

Anti-War is a big theme in both Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and in Princess Mononoke. In both movies, the main characters are trying to stop all of the wars. Nausicaä wants to stop the animals from fighting, as well as the main battle against the Pejitans and the Ohmu. In Princess Mononoke, Ashitaka tries to end the conflict between Irontown and the forest.

Flight

Flight is a recurring theme in many of Miyazaki’s films, with the exception of Princess Mononoke, in one form or another. In The Castle of Cagliostro, Lupin steals the Count’s autogyro. In Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Nausicaa uses a glider to get to places. And there are many airships in the movie, as well. There are also airships in Castle in the Sky and Porco Rosso. Porco Rosso is an air delivery pilot. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, Kiki regularly flies around on a broom and there is a blimp, as well as a homemade plane in the movie, too. In Spirited Away, Haku can turn into a dragon to fly around. In My Neighbor Totoro, Totoro flies around on a spinning top. And then, in Howl’s Moving Castle, Howl can turn in a bird and fly around. Howl’s Castle turns into a flying castle.

Visual Devices

The use of visual devices is common in all of Miyazaki’s film. He will pan away from the action for a few seconds to add a momentary lull to the movie. For instance, showing raindrops hitting a rock and darkening it has been used in several of his movies.

Politics

Miyazaki’s early interest in Marxism is apparent in a few of his films, such as Porco Rosso. In Castle in the Sky, the working class is portrayed in idealized terms.

The Cold War is a backdrop for The Castle of Cagliostro, where Zenigata’s plan to mobilize the ICPO against Count Cagliostro fails when the Soviet and American delegates accuse each other of the counterfeiting operation. The class divide is shown in the film by contrasting the Count hosting a lavish banquet in the castle with the Japanese police eating cheap ramen outside.

Influences

Miyazaki has cited several Japanese artists as his influences, including Sanpei Shirato, Osamu Tezuka, and Soji Yamakawa. A number of Western authors have also influenced his works, including Frédéric Back, Lewis Carroll, Roald Dahl, Jean Giraud, Paul Grimault, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Yuriy Norshteyn, as well as animation studio Aardman Animations.

Works

Movies

- 1968 Hols: Prince of the Sun (太陽の王子 ホルスの大冒険 , Taiyō no ōji Horusu no dai Bōken)

- Animator, Scene Designer

- 1979 The Castle of Cagliostro (ルパン三世 カリオストロの城 , Rupan Sansei: Kariosutoro no Shiro)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay, Character Designer

- 1984 Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (風の谷のナウシカ , Kaze no Tani no Naushika)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay

- 1986 Castle in the Sky (天空の城ラピュタ , Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay, Editor

- 1988 My Neighbor Totoro (となりのトトロ , Tonari no Totoro)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay

- 1989 Kiki’s Delivery Service (魔女の宅急便 , Majo no Takkyūbin)

- Director, Producer, Storyboard, Screenplay

- 1991 Only Yesterday (おもひでぽろぽろ , Omoide Poroporo)

- Producer

- 1992 Porco Rosso (紅の豚 , Kurenai no Buta)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay, Editor

- 1994 Pom Poko (平成狸合戦ぽんぽこ , Heisei Tanuki Gassen Ponpoko)

- Planner

- 1995 Whisper of the Heart (film) (Screenplay)

- Screenplay, Storyboard

- 1997 Princess Mononoke (もののけ姫 , Mononoke Hime)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay, Editor

- 2001 Spirited Away (千と千尋の神隠し , Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay

- 2002 The Cat Returns (猫の恩返し , Neko no Ongaeshi)

- Project Concept

- 2004 Howl’s Moving Castle (ハウルの動く城 , Howl no Ugoku Shiro)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay

- 2008 Ponyo (崖の上のポニョ, Gake no Ue no Ponyo)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay, Editor

- 2010 The Secret World of Arrietty (借りぐらしのアリエッティ , Kari-gurashi no Arietti)

- Screenplay

- 2011 From Up on Poppy Hill (コクリコ坂から Kokurikozaka kara)

- Screenplay

- 2013 The Wind Rises (風立ちぬ , Kaze Tachinu)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay

- 2023 How Do You Live? (きみたちはどういきるか , Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka)

- Director, Storyboard, Screenplay

Shorts

- 1972 Panda! Go, Panda! (パンダ・コパンダ , Panda Kopanda)

- Screen Design

- 1973 Panda! Go, Panda! and the Rainy-Day Circus (パンダ・コパンダ 雨降りサー スの巻 , Panda Kopanda: Amefuri Circus no Maki)

- Screen Design

- 1995 On Your Mark (ジブリ実験劇場 , Jiburi Jikkengekijō On Yua Māku)

- 2001 Koro’s Big Day Out (コロの大さんぽ , Koro no Daisanpo)

- 2001 The Whale Hunt (くじらとり?, Whale Hunt)

- 2002 Mei and the Kittenbus (めいとこねこバス , Mei to Konekobasu)

- 2006 The Day I Bought a Star (星をかった日 , Hoshi wo Katta Hi)

- 2006 Looking for a Home (やどさがし , Yadosagashi)

- 2006 Water Spider Monmon (水グモもんもん , Mizugumo Monmon)

- 2010 Mr. Dough and the Egg Princess (パン種とタマゴ姫 , Pandane to Tamago Hime)

- 2011 Treasure Hunting (たからさがし , Takara-sagashi)

- 2018 Boro the Caterpillar (毛虫のボロ , Kemushi no Boro)

TV

- 1964-65 Shonen Ninja-style Fujimaru (少年忍者風のフジ丸) (Toei Animation)

- Assistant Animator

- 1966-67 Rainbow Sentai Robin (レインボー戦隊ロビン) (Toei Animation)

- Assistant Animator

- 1969-70 Secret Akko-chan (ひみつのアッコちゃん) (Toei Animation)

- Based on the comics for girls by Fujio Akatsuka (赤塚不二夫)

- Assistant Animator

- 1969-70 Moomin (1969 TV series) (ムーミン) (Fuji TV, Zuiyo, Shin-ei Animation, TMS Entertainment)

- Animator

- 1971-72 Lupin the Third Part I (ルパン三世 (TV第1シリーズ) , Rupansansei (TV Dai 1 Shirīzu))

- Based on the comics by Monkey Punch (モンキー・パンチ)

- Worked with Isao Takahata, Animator

- 1972-73 Akado Suzunosuke (赤胴鈴之助) (Fuji TV, TMS Entertainment)

- Storyboard

- 1973 Jungle Kurobe (ジャングル黒べえ) (Mainichi Broadcasting System)

- Character Draft

- 1973-74 Samurai Giants (侍ジャイアンツ) (Yomiuri TV, TMS Entertainment)

- Animator

- 1974 Heidi, Girl of the Alps (Fuji TV , Zuiyo)

- Based on the novel of Johanna Spyri

- Scene Setting Screen Configuration

- 1975 Dog of Flanders (Fuji TV, Zuiyo, Nippon Animation)

- Based on the novel of Ouida

- Animator

- 1976 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother (Fuji TV, Nippon Animation)

- Based on one episode in the novel Cuore by Edmondo De Amicis

- 1978 Lupin the Third Part II (TMS Entertainment, Nippon Animation)

- Screenplay, Storyboard, Mechanical Design

- 1977 Rascal the Raccoon (Fuji TV, Nippon Animation)

- 1978 Future Boy Conan (未来少年コナン, Mirai Shōnen Konan)

- Director, Storyboard, Character Designer

- 1984 Sherlock Hound (探偵ホームズ, Meitantei Hōmuzu)

Other Works

Manga, Image Boards

- Puss in Boots

- People of the Desert

- Animal Treasure Island

- To My Sister (Collected in The World of Hayao Miyazaki and Yasuo Ōtsuka)

- Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (7 volumes)

- The Journey of Shuna

- Run Two Horsepower Run From The Wind (NAVI, December 1989 and CAR GRAPHIC , August 2010 issue)

- Meal in the Air (JAL WINDS, June 1994)

- Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind — Watercolor Painting Collection

- Princess Mononoke

- The Age of the Flying Boat (Dainippon Painting 1992, Supplementary Revised Edition 2004)

- Hayao Miyazaki’s Miscellaneous Notes (Dainippon Painting 1992, Supplementary Revised Edition 1997)

- The Youngest Brother of an Unknown Giant

- The Spirit of the Iron

- Multi-gun Tower Comes into Play

- Farmer’s Eyes

- Dragon Armor

- Heavy Bomber over Kyushu

- Flak Tower

- Q.ship

- Special Aircraft Carrier Yasumatsu Maru Monogatari

- Over London 1918

- The Poorest front

- Pig Tiger

- Hayao Miyazaki’s Daydream Data Notes (Dainippon Painting August 2002)

- Hans’s Return

- Muddy Tiger

- Blackham’s Bombing Machine by Robert Westall

- Edited by Hayao Miyazaki, translated by Mizuhito Kanehara (Iwanami Shoten, 2006)

- Water Depth Gohiro by Robert Westall

- Translation by Kinpara Mizujin, Kaori Nozawa (Iwanami Shoten, March 2009)

- The Wind Rises Hayao Miyazaki’s Delusional Comeback (Dainippon Painting, November 2015)

- Serialized in Model Graphics)

Design Work

- Wondership TVCM of Hitachi’s Maxell New Gold Videotape

- Pochette Dragon TVCM of Hitachi’s PC H2

- Ghost Ship in the live-action film Red Crow and the Ghost Ship

- Nandarō for Nippon Television Network

- Kanabee for the Kanagawa Dream National Athletic Meet

Lyrics

- Carrying You (Castle in the Sky theme song)

- My Neighbor Totoro (My Neighbor Totoro theme song)

- Le Chemin du Ven (My Neighbor Totoro insert song)

- Country Road (Whisper of the Heart theme song)

- Baron no Uta (Whisper of the Heart image album)

- Princess Mononoke (Princess Mononoke theme song)

- Tatara Song (Princess Mononoke insert song)

Books, Interviews

- House Where Totoro Lives

- Picture collection, Hisashi Wada, Asahi Shimbun (1991), Iwanami Shoten (January 2011)

- Once in a while, let’s talk

- Picture book, co-authored with Tokiko Kato, Tokuma Shoten (1992)

The Wind of the Times

-

- Dialogue with Ryotaro Shiba and Yoshie Hotta, UPU (1992), Asahi Bunko Bunko (1997)

- What is a movie, Seven Samurai and Maadayo

- Interview with Akira Kurosawa, Studio Ghibli (1993)

- Going to see the giant tree — Encounter with life for a thousand years

- Co-authored by Miyazaki, Kodansha Culture Books (1994)

- Starting point 1979-1996

- Essays, Tokuma Shoten (1996)

- About Education

- Co-authored by Miyazaki, Shunposha (1998)

- Magical Eyes and Ani Eyes

- Interview with Takeshi Yoro, Studio Ghibli (2002), Shincho Bunko (February 2008)

- The place where the wind returns-the trajectory from Nausicaa to Chihiro

- Interview collection by Yoichi Shibuya, Rockin’on (2002), Bungei Ghibli Bunko (November 2013)

- Turning point 1997-2008

- Essays, Iwanami Shoten (2008)

- Tobira to Books-Talking about Iwanami Shonen Bunko

- Introduction of 50 Recommended Books) Iwanami Shinsho Color Edition (October 2011)

- Koshinuke Patriotic Talk

- Interview with Kazutoshi Hando, Bungei Ghibli Bunko (August 2013)

- The place where the wind returns-How did the movie director Hayao Miyazaki start and how did the curtain come to an end?

- Interview collection by Yoichi Shibuya, Rockin’on (2013)

Cover Illustration

- Chesterton’s 1984 / New Napoleon Kitan (Gilbert Chesterton), Shunjusha Publishing (1984)

- The Witches of Kares on the Planet (James Henry Schmitz ), Shincho Bunko (1987), Sogen Suiri Bunko (1996)

- Night Flight (Saint Exupery), Shincho Bunko (1993, revised 2012) * New cover

- Human Land (Saint Exupery), Shincho Bunko (1998, revised 2012) * New cover

- Midnight Phone (Robert Westall), Tokuma Shoten (2014)

- Call of a Far Day (Robert Westall), Tokuma Shoten (2014)

- Ghost Tower (Ranpo Edogawa), Iwanami Shoten (2015)

References

- ↑ «Turning Point 1979-1996]», Afterword

- ↑ «Momoru Oshii Interview», Nausicaa

External links

«Whenever we get stuck at Pixar or Disney, I put on a Miyazaki film sequence or two, just to get us inspired again,» said John Lasseter, director of Toy Story. This explains the influence of Miyazaki’s films on animation industries in the world, extending far beyond its home nation of Japan. Studio Ghibli is responsible for placing the art of Japanese animated films onto the map of the world. These films often featuring female characters being thrust into lead roles as powerful, independent heroines challenging stereotypical images of Japanese women submitting to the yoke of patriarchy. This often leads many to consider Ghibli films as feminist in nature. Consequently, this triggers the question of whether these films would be able to pave the way for stronger portrayal of women in Japanese anime. This research paper examines the role of the stereotype-breaking female in Japanese animated films that change the mindset of a patriarchal Japanese animation industry, with special attention to 1) gender equality, 2) roles for women, and 3) common stereotypes. The case studies analyzed include scenes from Ghibli films will be used focusing on three of Studio Ghibli’s most popular works directed by Hayao Miyazaki, namely, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Princess Mononoke (1997) and the Oscar-winning Spirited Away (2001). This investigation considers the strong portrayal of women in these films to be pivotal in sparking discussions of gender inequality towards the strengthening of portrayals of women in the Japanese animation industry. With close examination of how women are depicted on screen in Ghibli animations, this project provides an insight on the seldom discussed issue of female roles in the anime business.

Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki works

Ghibli Museum, Mitaka.zip

Hayao Miyazaki — Daydream Note.zip

HAYAO MIYAZAKI IMAGE BOARD.zip

Mei and the Kittenbus Artbook- A Short Film by Hayao Miyazaki.zip

Miyazaki Hayao Artbooks Scenes Chapter(chinese).zip

Mizugumo Monmon [Studio Ghibli].zip

Studio Ghibli Layout Designs — Understanding the Secrets of Takahata-Miyazaki Animation.zip

The Art of Howl’s Moving Castle- A Film by Hayao Miyazaki.zip

The Art of Kiki’s Delivery Service- A Film by Hayao Miyazaki.zip

The Art of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind- A Film by Hayao Miyazaki.zip

The Art of Porco Rosso- A Film by Hayao Miyazaki.zip

The Art of Howl’s Moving Castle — A Film by Hayao Miyazaki.zip

Nausicaa (Shuna No Tabi) — 01

Nausicaa (Shuna No Tabi) — 02

Nausicaa (Shuna No Tabi) — 03

Nausicaa (Shuna No Tabi) — 04

Nausicaa (Shuna No Tabi) — 05

Nausicaa (Shuna No Tabi) — 06

О студии Studio Ghibli (スタジオジブリ)

Японская анимационная студия. Её основал в 1985 году режиссёр и сценарист Хаяо Миядзаки вместе со своим коллегой и другом Исао Такахатой при поддержке компании Tokuma, которая впоследствии совместно с Walt Disney будет распространять «Принцессу Мононокэ» и «Унесённых призраками». На логотипе студии изображён Тоторо, персонаж из фильма «Мой сосед Тоторо», выпущенного Studio Ghibli в 1988 году. Звуковое сопровождение к большинству фильмов написал Дзё Хисаиси. Studio Ghibli одной из первых японских фирм начала активно использовать в анимации компьютеры. Студия была основана в городе Мусасино.

Studio Ghibli (Studio Ghibli, Inc.) is a Japanese animation studio based in Koganei, Tokyo. It is best known for its range of animated feature films, and has also produced several short subjects, television commercials, and two television films. Its mascot and most recognizable symbol is a character named Totoro, a giant spirit inspired by raccoon dogs (Tanuki) and cats from the 1988 anime film My Neighbor Totoro. Among the studio’s highest-grossing films are Spirited Away (2001), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and Ponyo (2008). The studio was founded on June 15, 1985, by the directors Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata and producer Toshio Suzuki, after acquiring Topcraft’s assets.

В работе 8 аниме в этом месяце.

When animation director Hayao Miyazaki founded his own studio in 1985, he called it Studio Ghibli, a name that would soon become synonymous with the finest animated features produced in almost any country in the world. Not every Studio Ghibli release has been directed by Miyazaki, but his guiding hand is clearly behind all productions released through the company.

Here are the major releases from Studio Ghibli, in chronological order. Note that this list is limited to titles with U.S. / English-language releases.

Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Studio Ghibli’s Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind.

Studio Ghibli

Miyazaki’s first feature production with him as the director still ranks among his very best, if not also the best in all of anime. Adapted from Miyazaki’s own manga, also in print domestically, it deals with a post-apocalyptic world where a young princess (the Nausicaä of the title) fights to keep her nation and a rival from going to war over ancient technology that could destroy them both. There are endless allusions to modern-day issues—the nuclear arms race, ecological consciousness—but all that takes a backseat to a tremendously engaging story told with beauty and clarity. The original U.S. release (as «Warriors of the Wind») was infamously cut down, which left Miyazaki wary of distributing his films in the U.S. for almost two decades.

Castle in the Sky (1986)

Studio Ghibli’s Laputa Castle in the Sky.

© 1986 Nibariki — G

Also known as »Laputa,» this is another of Miyazaki’s grand and glorious adventures, loaded with imagery and sequences that reflect his love of flying. Young villager Pazu encounters a girl named Sheeta when she falls from the sky and practically lands in his lap; the two learn that the pendant in her possession could unlock untold secrets within the “castle in the sky” of the title. As in »Nausicaä,» the young and innocent must grapple against the machinations of cynical adults, who only have eyes for the city’s war machines. (This was the first true Studio Ghibli production; «Nausicaä» was officially done by the studio Topcraft.)

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

Studio Ghibli’s Grave of the Fireflies.

Studio Ghibli

Directed by Ghibli cohort Isao Takahata, this is a grim depiction of life (and death) during the last days of WWII when Allied firebombings claimed many civilian lives in Tokyo—a story that has not been reported as often as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Derived from Akiyuki Nosaka’s novel, it shows how two youngsters, Seita and his little sister Setsuko, struggle to survive in the charred ruins of the city and fend off starvation. It’s difficult to watch, but also impossible to forget, and definitely not a children’s movie due to the graphic way it depicts the aftermath of war.

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

Studio Ghibli’s My Neighbor Totoro.

© 1988 Nibariki/Studio Ghibli

Easily the most beloved of any of Miyazaki’s films, and more than almost any of his others about the world as seen through the eyes of children. Two girls have relocated with their father to a house in the country, to be close to their ill mother; they discover the house and the surrounding forest is a veritable hotbed of supernatural spirits, who play and keep them company. A synopsis doesn’t do justice to the movie’s plot, gentle atmosphere, where what happens isn’t nearly as important as how it’s seen by Miyazaki and his creative team. Most any parent should grab a copy of this for their kids.

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

Studio Ghibli’s Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Studio Ghibli

A sprightly adaptation of a beloved children’s book from Japan (also now in English), about a young witch-in-training who uses her broom-riding skills to work as a courier. It’s more about whimsy and characters colliding than plot, but Kiki and the clutch of folks she befriends are all fun to watch. Spectacular to look at, too; the Ghibli crew created what amounts to a fictional European-town flavor for the film. The biggest problem is the last 10 minutes or so, a five-car pileup of storytelling which injects a manufactured crisis where one wasn’t really needed.

Porco Rosso (1992)

Studio Ghibli’s Porco Rosso.

Studio Ghibli

The title means “The Crimson Pig” in Italian, and it sounds like unlikely material: a former fighter pilot, now cursed with the face of a pig, ekes out a living as a soldier of fortune in his seaplane. But it’s a delight, fusing a post-WWI European setting with Miyazaki’s always-idyllic visuals—it could almost be considered his response to »Casablanca.» Originally intended to be a short in-flight film for Japan Airlines, it was expanded into a full feature. Michael Keaton (as Porco) and Cary Elwes are featured in Disney’s English dub of the movie.

Pom Poko (1994)

Studio Ghibli’s Pom Poko.

Studio Ghibli

A cadre of shapeshifting Japanese raccoons, or tanuki, collide with the nature-threatening ways of the modern world. Some of them choose to resist the encroachment of humankind, in ways that resemble eco-saboteurs; some instead opt to assimilate into human life. It’s a great example of how anime often mines Japan’s mythology for inspiration, although note there are some moments that might not be suitable for younger viewers.

Whisper of the Heart (1995)

Studio Ghibli’s Whisper of the Heart.

Studio Ghibli

A girl with ambitions to be a writer and a boy who dreams of becoming a master violin-maker cross paths and learn to inspire each other. The only feature directed by Yoshifumi Kondo, whom Miyazaki and Takahata had high hopes for (he also worked on «Princess Mononoke») but whose directorial career was cut short by his sudden death at the age of 47.

Princess Mononoke (1997)

Studio Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke.

Nibariki — GND

In a land reminiscent of premodern Japan, young Prince Ashitaka sets out on a journey to discover a cure for a festering wound he received at the hands of a strange beast—a wound which also gives him great power at a terrible cost. His journey brings him into contact with the princess of the title, a wild child who’s allied herself with the spirits of the forest to protect it against the encroachment of the haughty Lady Eboshi and her forces. It’s in some ways a differently-flavored reworking of «Nausicaä,» but hardly a clone; it’s as exciting, complex and nuanced a film (and as beautiful a one) as you’re likely to see in any medium or language.

My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999)

Studio Ghibli’s My Neighbors the Yamadas.

Studio Ghibli

An adaptation of Hisaichi Ishii’s slice-of-life comic strip about a family’s various misadventures, it broke rank from the other Ghibli productions in its look: it sticks closely to the character designs of the original comic but reproduced and animated in a gentle watercolor style. The story has little plot, but rather a series of loosely-connected scenes that work as comic meditations on family life. Those expecting adventures in the sky or any of the other Ghibli hallmarks may be disappointed, but it’s still a sweet and enjoyable movie nonetheless.

Spirited Away (2001)

Studio Ghibli’s Spirited Away.

© 2001 Nibariki — GNDDTM

Miyazaki was allegedly prepared to retire after «Mononoke;» if he had, he might not have made yet another of the top films of his career and the most financially successful of all of Studio Ghibli’s films so far ($274 million worldwide). Sullen young Chihiro is jolted out of her shell when her parents disappear, and she’s forced to redeem them by working in what amounts to a summer resort for gods and spirits. The film’s crammed with the kind of quirky, Byzantine delights you might find in one of Roald Dahl’s books for kids. Miyazaki’s amazing sense of visual invention and his gentle empathy for all his characters, even the “bad” ones, also shine through.

The Cat Returns (2002)

Studio Ghibli’s The Cat Returns.

Nibariki — GNDDTM

A cheeky fantasy about a girl who saves a cat’s life, and is repaid by being invited to the Kingdom of the Cats—although the more time she spends there, the greater the risk she’ll never be able to get back home. A follow-up, sort of, to «Whisper of the Heart:» the cat is the character in the story written by the girl. But you needn’t see Heart first to enjoy this charming version of Aoi Hiiragi’s manga.

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle.

Studio Ghibli

An adaptation of Dianne Wynne Jones’s novel, wherein a girl named Sophie is transformed by a curse into an old woman, and only the magician Howl—the owner of the “moving castle” of the title—can undo the damage. Many of Miyazaki’s trademark elements can be found here: two feuding kingdoms, or the amazing design of the castle itself, fueled by a fire demon who enters into a pact with Sophie. Miyazaki was actually a replacement for the original director, Mamoru Hosoda (»Summer Wars,» «The Girl Who Leapt Through Time»).

Tales From Earthsea (2006)

Studio Ghibli’s Tales of Earthsea.

Studio Ghibli

Miyazaki’s son Goro took the helm for this loose adaptation of several books in Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea series. LeGuin herself found the movie departed drastically from her works, and critics lambasted the finished product for being technically impressive but a storytelling jumble. It remained unreleased in the U.S. until 2011.

Ponyo (2008)

Studio Ghibli’s Ponyo.

Studio Ghibli

Described as Miyazaki’s «Finding Nemo,» «Ponyo» is aimed at younger audiences in much the same way that »Totoro» was: it sees the world as a child would. Little Sosuke saves what he thinks is a goldfish but is actually Ponyo, daughter of a magician from deep within the sea. Ponyo takes on human form and becomes a playmate to Sosuke, but at the cost of unhinging the natural order of things. The stunning, hand-drawn details that crowd almost every frame—the waves, the endless schools of fish—are a real treasure to watch in an age when most such things are spat out of computers.

The Secret World of Arrietty (2011)

Studio Ghibli’s The Secret World of Arrietty.

Studio Ghibli

Another successful adaptation of a children’s book, this one based on Mary Norton’s «The Borrowers.» Arrietty is a little girl— very little, as in only a few inches high — and lives with the rest of her «Borrower» family under the noses of a regular human family. Eventually, Arrietty and her kin must enlist the help of the human family’s youngest son, Sho, lest they are driven from their hiding places.

From Up On Poppy Hill (2011)

Studio Ghibli’s From Up On Poppy Hill.

Studio Ghibli

Against the backdrop of a bustling postwar Japan preparing for the 1964 Olympics, a girl who lost her father to the Korean War strikes up a tentative friendship—and possibly more—with a boy in her class. The two of them team up to save the school’s dilapidated clubhouse from demolition but then discover they share a connection that neither of them could have possibly foreseen. The second film (after »Tales from Earthsea») in the Ghibli stable to have been directed by Hayao Miyazaki’s son Goro, and it’s a far better one.

The Wind Rises (2013)

Studio Ghibli’s The Wind Rises.

Studio Ghibli

This is a fictionalized story of the life of Jiro Horikoshi, the designer of the Mitsubishi A5M and the A6M Zero, Japan’s fighter aircraft of World War II. The nearsighted boy wants to be a pilot but dreams of Italian aircraft designer Giovanni Battista Caproni, who inspires him to design them instead. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature and the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013)

Studio Ghibli’s Tale of the Princess Kaguya.

Studio Ghibli

A bamboo cutter discovers the title character as a tiny girl inside a glowing bamboo shoot and also finds gold and fine cloth. Using this treasure, he moves her to a mansion when she comes of age and names her Princess Kaguya. She is courted by noble suitors and even the Emporer before revealing that she came from the moon. This movie was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.

When Marnie Was There (2014)

Studio Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There.

Studio Ghibli

This was the final film for Studio Ghibli and animator Makiko Futaki. Twelve-year-old Anna Sasaki lives with her foster parents and is recuperating from an asthma attack in a seaside town. She meets Marnie, a blonde girl who lives in a mansion that sometimes appears dilapidated and at other times is fully restored. This movie was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.

На КиноПоиск HD появился большой пакет мультфильмов легендарной Studio Ghibli (со всей доступной к просмотру фильмографией студии можно ознакомиться тут). О том, как лучше спланировать путешествие в этот волшебный мир, населенный веселыми оборотнями, заколдованными принцами, фантастическими и выдуманными существами и самыми обычными японцами, рассказывает Павел Шведов.

35 лет назад друзья и коллеги Хаяо Миядзаки и Исао Такахата основали анимационную студию Ghibli. По большому счету именно она и открыла миру феномен японской анимации: успех Ghibli, продукция которой была одинаково понятна и близка зрителям из совершенно разных стран, не смогла повторить ни одна другая аниме-студия. Фильмы отцов-основателей и их учеников очень разные. К примеру, Такахата предпочитал адаптировать литературные произведения, пускался в эксперименты с формой и стилем рисунка и выбрал местом действия Японию, а Миядзаки находился под сильным влиянием европейской визуальной культуры и экологического движения. Это многообразие породило настоящую вселенную Ghibli, не ограниченную фантазией одного автора, единой темой или художественным стилем и, тем не менее, вполне узнаваемую по характерному, очень органичному сочетанию реалистических и сказочных элементов, фольклорных мотивов и злободневных проблем, с которыми сталкиваются ее обитатели.

Если карточка фильма черная, значит, его можно посмотреть на КиноПоиск HD. Обо всех возможностях нашего онлайн-кинотеатра читайте в специальном гиде.

«Унесенные призраками»

Главный хит Ghibli

Начать знакомство с мультфильмами Studio Ghibli стоит, конечно, с работы ее отца-основателя и самого известного из авторов — Хаяо Миядзаки. «Унесенные призраками» — его главный фильм. В мировом прокате он заработал более 270 млн долларов (что в 14 раз больше бюджета), получил «Оскар», «Золотого медведя» Берлинале, четыре анимационные премии «Энни» и еще более 50 наград по всему миру. Фильм входит во все мировые чарты лучшей анимации.

Главная героиня «Унесенных» — десятилетняя Тихиро. Вместе с родителями она переезжает в сельскую местность. По пути в новый дом отец Тихиро ошибается дорогой, и семья оказывается в заброшенном городке. Увидев в безлюдном ресторанчике вкусно пахнущую еду, родители решают поесть, и вдруг оживает древняя магия. Заброшенный город оказывается населен демонами, духами и волшебными существами, а прожорливые мама с папой превращаются в свиней. Тихиро придется пройти через множество испытаний, чтобы избавить своих родителей от чар и вернуться в мир людей.

Девочки, которые через игру и испытания получают новый опыт и буквально взрослеют духом, — постоянный мотив историй Миядзаки. Женские персонажи исследуют и спасают окружающий мир не только в «Унесенных призраками», но и в «Небесном замке Лапута», «Моем соседе Тоторо», «Рыбке Поньо на утесе», «Ведьминой службе доставки». Такое смещение гендерного акцента в фильмах Ghibli позволяет зрителю взглянуть по-новому на классический сюжет спасения мира, в центре которого обычно оказывались однообразные маскулинные герои.

«Принцесса Мононоке»

Первый прорыв Миядзаки на Запад

Именно «Принцесса Мононоке» пробудила интерес международной аудитории к фильмам Хаяо Миядзаки и студии Ghibli вообще: фильм был куплен для широкого американского проката компанией Miramax, переведен Нилом Гейманом и дублирован (исключительный случай для японской анимации на американском рынке). Правда из-за плохой рекламной кампании (и самого факта дубляжа) театральный прокат прошел плохо, и «Принцесса Мононоке» стала куда популярнее после издания на DVD с японской дорожкой.

А ведь картина могла стать последней в творчестве Миядзаки. Он создал первые наброски к истории о принцессе, живущей в лесу, еще в 1970-е, а в конце 1990-х, планируя уйти из режиссуры, решил обратиться к классическому для себя экосюжету об уничтожении первозданной природы человеческой цивилизацией (об этом же и «Навсикая из долины ветров», и «Небесный замок Лапута», и «Рыбка Поньо на утесе», и «Ходячий замок»). Средневековая Япония становится полем битвы людей и лесных божеств. На стороне леса — Сан, девушка, воспитанная богиней-волчицей. На стороне людей — леди Эбоси, которая развивает Железный город, вырубая для этих целей заповедный лес. Юный принц Аситака изо всех сил пытается примирить враждующие стороны. Но борьба становится все более кровавой, и надежда, кажется, потеряна навсегда.

В итоге «Принцесса Мононоке» стала первой анимационной картиной, завоевавшей награду Японской киноакадемии в номинации «Лучший фильм года». Так что Миядзаки передумал уходить и с тех пор снял еще четыре блистательные работы.

«Навсикая из долины ветров»

С которой все и началось

Команда будущей студии Ghibli фактически оформилась в 1983 году — как раз во время работы над «Навсикаей» (например, продюсером картины стал Исао Такахата; о его собственных фильмах мы рассказываем ниже). Несмотря на то, что студия официально была создана только через год после премьеры истории о храброй княжне, этот фильм включается во все ее ретроспективы. Его сюжет — все та же притча о конфликте человека и натуры. Навсикая, властительница Долины ветров, живет в мире, опустошенном «семью днями огня» — разрушительным холокостом, практически до неузнаваемости изменившим природу. Но братоубийственные войны еще продолжают бушевать на планете, грозя человечеству окончательной гибелью. Навсикая пытается сохранить хрупкий баланс в постапокалиптическом мире.

Опрос, проведенный министерством культуры Японии в 2007 году, поставил «Навсикаю из долины ветров» на второе место среди аниме всех времен.

«Мой сосед Тоторо»

Тут появился самый узнаваемый персонаж студии

Сестры Сацуки и Мэй переезжают вместе с папой в деревенский дом. Девочки открывают новый для себя мир, населенный, как оказалось, не только людьми. Однажды младшая непоседливая Мэй знакомится с лесными духами — хранителями леса Тоторо, живущими в камфорном дереве. Один из Тоторо, похожий на гигантского полукота и полузайца, постепенно становится другом девочек, сопровождая их в ежедневных похождениях и приключениях.

Производство фильма было рискованным шагом: мало кто верил в зрительский успех картины про приключения двух девочек с троллеподобным монстром в сельской местности. В первое время его спасала только связка с «Могилой светлячков» — антивоенным гимном Такахаты, выпущенным одновременно с историей о Тоторо (комплект из двух фильмов продавался в японские школы для уроков истории и эстетического воспитания). Постепенно любовь зрителей превзошла все даже самые оптимистичные ожидания. Образы Тоторо, кота-автобуса, черных чернушек оказались популярными среди зрителей всех возрастов, а профиль заглавного доброго лесного духа оказался на логотипе Ghibli. Кстати, именно «Тоторо» впервые познакомил российских зрителей с творчеством Миядзаки — его выпустили в советский прокат уже в 1989 году!

«Порко Россо»

Два любимых мотива Миядзаки — Европа плюс авиация

«Порко Россо» был задуман как короткометражка для показа во время полетов самолетами Japan Airlines. Он должен был стать фильмом, «которым уставшие бизнесмены на международных рейсах могут наслаждаться, не замечая недостатка кислорода». Но Миядзаки отошел от первоначального замысла и сделал полный метр об итальянском пилоте ВВС, который ушел с армейской службы из-за подъема фашизма в родной стране и стал вольным стрелком под псевдонимом Порко Россо.

Несмотря на мрачный контекст и вообще недетскую историю, «Порко Россо» — настоящая визуальная феерия: эффектные воздушные поединки происходят на фоне волшебных средиземноморских пейзажей. Поэзия европейских ландшафтов вообще очень сильно повлияла на студийную эстетику Ghibli. «Ведьмина служба доставки» наполнена видами скандинавских городов, образы «Небесного замка Лапута» основаны на валлийском шахтерском городке, в «Шепоте сердца» узнается итальянская Кремона, а Хаул бродит в своем замке по неназванным, но определенно европейским пустошам.

«Помпоко: Война тануки в период Хэйсэй»

Главный фильм Такахаты, второго отца-основателя студии

Фильм Исао Такахаты (а продюсером тут стал уже Миядзаки) — уникальное окно в мир японской истории и фольклора, связанных здесь тесно, почти неразрывно. Его фабула не станет сюрпризом для фанатов Миядзаки: человеческая цивилизация, расширяясь, захватывает лесные территории и все сильнее мешает привычному укладу древнего народа. Только вместо выдуманных специально для мультфильма богов и существ (как у Миядзаки) Такахата делает своими героями обычных фольклорных персонажей — тануки, енотовидных собак-оборотней. Озорные тануки не унывают и, используя свой магический навык превращения, пытаются отпугнуть людей и остановить вырубку лесов ради строительства жилых кварталов. Подобно самим тануки, фильм постоянно меняет обличья: то он комедия, то волшебная сказка, то притча, то трагедия. Снятый в середине 1990-х, когда Япония переживала экономический кризис, «Помпоко» обращается к событиям 1960-х, когда строительный бум и расширение Токио разрушили не только природу, но и традиционный образ жизни крестьян.

«Наши соседи Ямада»

Новый стиль — акварельное аниме

В одном японском городе живет одна совершенно обычная японская семья Ямада. Сильно устающий на работе отец. Мать, полностью погруженная в семейный быт. Сын-старшеклассник с ворохом подростковых проблем. Жизнерадостная дочка, ученица в начальной школы. Сварливая, но полная энергии в свои 70 лет теща. И любимый всей семьей пес, молчаливо наблюдавший за смешным круговоротом разворачивающейся вокруг жизни.