Сегодня в Китае желающие получить государственную должность сдают специальные экзамены на высокий результат. Лишь лучшие из лучших могут занимать чиновничьи посты, даже на низком уровне. Эта практика берет начало из древней экзаменационной системы «кэцзюй» (科举 kējǔ) и существует уже на протяжении более 1000 лет! Только испытаниями Китай обеспечивал справедливый и беспристрастный процесс отбора и гарантировал высокую компетентность действующих должностных лиц. ЭКД рассказывает, как отбирали кандидатов и удавалось ли кому-то списать.

Кэцзюй создали на замену несправедливой системе

Императорская экзаменационная система кэцзюй была создана в период Суй (581—618 гг.). Она заменила существующую прежде «систему девяти рангов» (九品 jiǔpǐn), по которой местные власти, исходя из собственных представлений, оценивали таланты и нравственные качества кандидатов, претендующих на государственный пост.

Согласно выставленным оценкам, испытуемые занимали освободившиеся государственные места и получали одно из девяти званий. Однако такой механизм часто подвергался влиянию знатных семей, что мешало справедливому и беспристрастному процессу отбора. Поэтому систему было решено заменить на кэцзюй, где решение о назначении принимало независимое центральное правительство.

Наибольшее развитие кэцзюй получил во время империи Тан (618—907 гг.). Тогда впервые начало складываться представление об образовательном процессе, появилась система, регулирующая отношения между учителем и учеником, а также установили время учебы, экзаменов и каникул. Если раньше для получения должности необходимо было иметь высокое происхождение, то с экзаменационной системой все стало более демократично. Практически каждый желающий мог попробовать свои силы. Другое дело, что далеко не все имели достаточно средств, чтобы просто доехать до места проведения испытания. Что уж говорить о качественной подготовке.

За несколько столетий существования процедура проведения экзамена неоднократно менялась. Однако изменения носили скорее косметический характер и не затрагивали основную идею: пройти несколько испытаний. К периодам Мин (1368—1644 гг.) и Цин (1644—1912 гг.) эта система становится все более коррумпированной и устаревшей. Лица знатного происхождения могли подкупать экзаменаторов, а иногда даже пропустить один из этапов благодаря своим связям и положению. Поэтому неудивительно, что в 1905 году кэцзюй был отменен.

Экзамен был трехуровневым

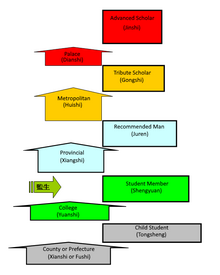

В период Сун (960—1279 гг.) экзамен сформировался в виде трехуровневой системы. Первой ступенью считалось звание сюцай (秀才 xiùcái), испытание на которое проводилось раз в год в уездных центрах страны. Возрастных ограничений для участников не было. В истории даже были случаи, когда один и тот же экзамен вместе сдавали отец и сын. Кандидаты должны были написать сочинение по истории и философии и сочинить стихотворение. В случае успешного прохождения первого этапа экзаменуемые допускались к следующему.

Экзамен на степень цзюйжэнь (举人 jǔrén) проводился в провинциальных центрах каждые три года. Здесь участникам предстояло написать несколько сочинений по работам Конфуция и других известных мыслителей. Экзаменаторы проверяли знания в области истории, географии и государственного устройства страны. Оценивалось не только содержание работ, но и каллиграфические навыки кандидатов.

Самым трудным и ответственным считался этап на звание цзиньши (进士 jìnshì), проводившийся в столице раз в три года. Здесь мог присутствовать сам император. Успешное прохождение этой части экзамена предоставляло возможность поступить на государственную службу и претендовать на высокую должность в императорском чиновничьем аппарате.

Пройти весь экзаменационный путь удавалось лишь единицам. Зачастую высшей ступени достигали уже немолодые мужчины, иногда старше 70 лет. Тем не менее, высокие результаты даже за первые ступени экзамена обеспечивали определенными привилегиями и предоставляли возможность работать в органах местного самоуправления.

Выходить с экзамена не разрешали

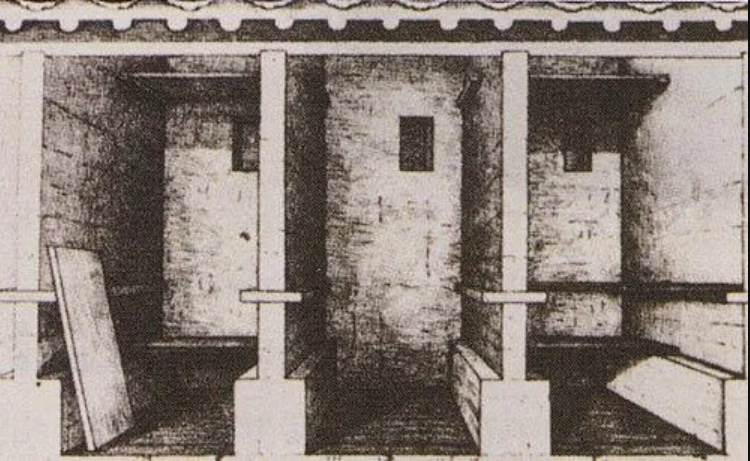

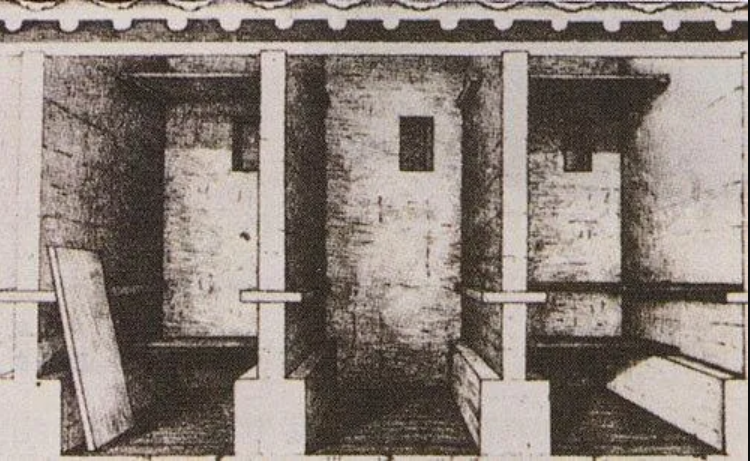

Кэцзюй имел строгую процедуру проведения и очень жесткие требования к участникам. Каждый кандидат получал задание и отправлялся в маленькую кабинку, известную как каочан (考场 kǎochǎng) или каопэн (考棚 kǎopéng). Здесь располагалось две доски, на которых можно было сидеть, писать или спать. Обычно экзамен длился несколько дней, и покидать экзаменационное помещение за все это время было запрещено.

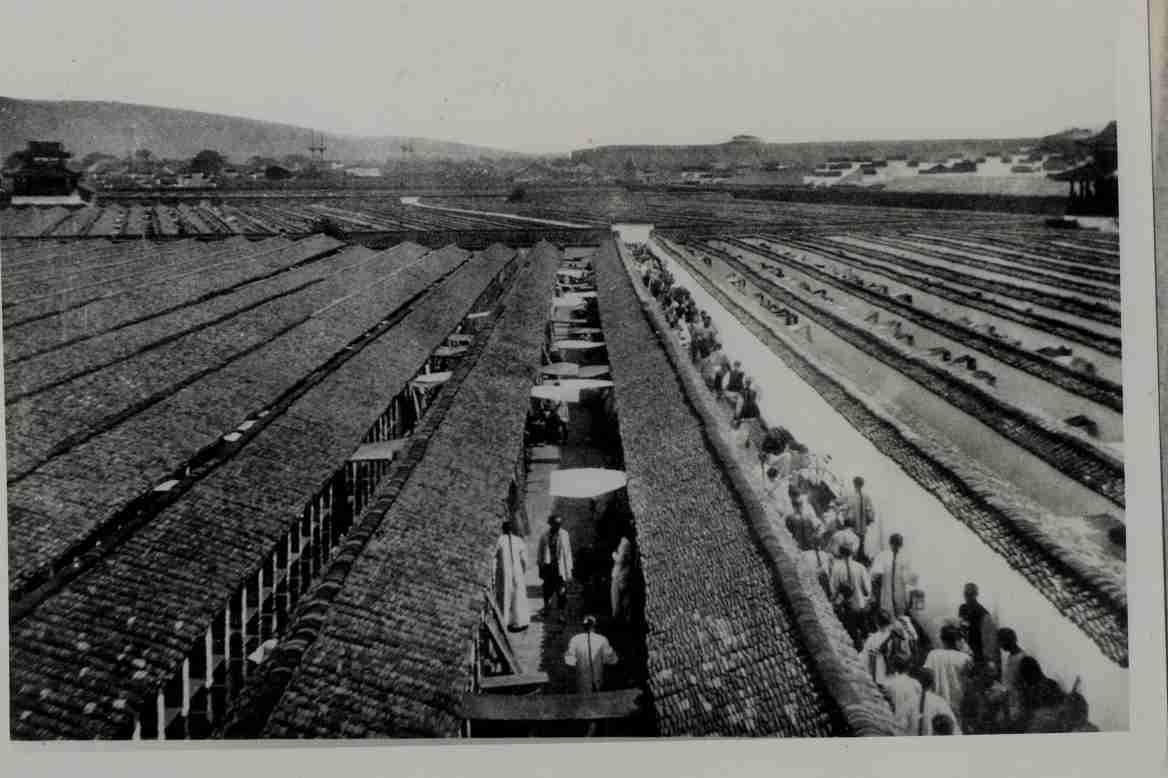

Экзаменуемые приносили с собой еду, воду, туалетные и письменные принадлежности, которые тщательно обыскивались на наличие вспомогательных материалов. Кандидаты должны были по памяти приводить точные цитаты конфуцианских канонов, по возможности избегая современных выражений и слов. Самый большой экзаменационный двор находился в Нанкине. Здесь могло разместиться 20,6 тыс. испытуемых.

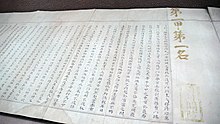

Участники не подписывали свои работы. Каждая была специально пронумерована, чтобы экзаменаторы могли беспристрастно оценить полученные ответы. В 14 веке была утверждена особая форма и структура для сочинений, получившая название «багувэнь» (八股文 bāgǔwén) и состоящая из восьми частей: вступление (破题 pòtí), прояснение темы (承題 chéngtí), общее рассуждение (起讲 qǐjiǎng), зачин рассуждения (起股 qǐgǔ), центральная часть рассуждения (中股 zhōnggǔ), окончание рассуждения (后股 hòugǔ), последний аргумент (束股 shùgǔ) и общий итог (大结 dàjié). Для каждого раздела существовали определенные требования и критерии, позволяющие оценить и проверить уровень начитанности и образованности экзаменующегося.

На экзамене списывали

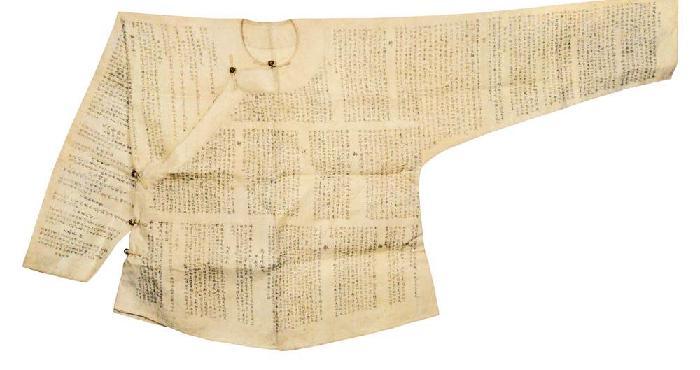

Из-за того, что экзамены были очень сложными, уже тогда существовала практика списывания и мошенничества. Испытуемые писали тексты на внутренних подкладках одежды и обуви или даже на теле, а иногда просили другого человека пройти экзамен вместо себя. Некоторые использовали в качестве шпаргалок крошечные кусочки из золотой фольги, которые можно было с легкостью спрятать под чернильным камнем или среди туалетных принадлежностей, а также миниатюрные книги.

«Полные заметки к пяти классическим произведениям» (五经全注 Wǔjīng quán zhù) — одна из самых маленьких книг в мире, которая была написана для помощи сдающим кэцзюй. Она насчитывает 342 страницы и 300 тыс. иероглифов. Ее длина составляет 6,5 см, ширина — 4,8 см, а толщина — всего 1,5 см!

Уже тогда использовались специальные чернила, которые исчезали после написания. Кандидаты записывали всю необходимую информацию на одежде, а когда заходили в кабинку, посыпали ткань грязью, и текст появлялся вновь. Наиболее состоятельные кандидаты также пытались подкупить экзаменаторов. Они писали в своей работе определенный набор слов, по которым можно было идентифицировать их работу, и проверяющий, увидев эти слова, сразу же ставил высокую оценку. Иногда им даже удавалось договориться с надсмотрщиком, чтобы тот принес в экзаменационную комнату нужную книгу.

При обнаружении списывания наказывались все экзаменуемые. В этом случае никому из участников не давали степень, и все результаты аннулировались. Поэтому в интересах каждого было контролировать процесс проведения экзамена и доносить на нарушителей. Мошенников можно было пожизненно отстранить от участия в конкурсе, посадить в тюрьму и даже казнить.

Ответственность за случившееся несли и сами наблюдатели, которые не смогли быстро и своевременно отреагировать на нарушение. В 1859 году, в период Цин (1636—1912 гг.), один из проверяющих был публично казнен за неоднократное получение взяток от испытуемых.

Женщины участвовать не могли

Девушки к экзаменам не допускались. Они должны были заниматься домашним хозяйством и воспитанием детей. Тем не менее, были случаи, когда женщины пытались обхитрить проверяющую комиссию и выдавали себя за мужчин.

Однажды в период правления маньчжурского императора Цяньлун (乾隆 qiánlóng) (1735-1796 гг.) в Янчжоу провинции Цзянсу жил мужчина, который не обладал знаниями и амбициями, достаточными для участия в конкурсе. Однако его жена была крайне умной и образованной и очень хотела повысить социальный статус своей семьи. Тогда она взяла одежду своего мужа и отправилась на экзамен вместо него.

К сожалению, ей так и не удалось попробовать свои силы: обман тут же раскрылся. В результате, женщина посвятила себя воспитанию сыновей и обучила их всем секретам и хитростям подготовки. Благодаря ее пристальному контролю мальчики смогли успешно сдать кэцзюй и в будущем стали чиновниками.

Считалось, что чиновники должны представлять собой исключительно «достойных и честных» людей. Поэтому к экзаменам также не допускались рабы, актеры, преступники и дети продажных женщин.

Подготовка начиналась с раннего детства

В возрасте 4-5 лет у детей появлялись личные наставники и преподаватели, которые учили их писать на классическом китайском языке, значительно отличающемся от разговорного. Мальчики заучивали конфуцианские тексты, учили историю, императорские указы и постановления, а также развивали навыки каллиграфии и знакомились со структурой восьмичленного сочинения «багувэнь». Нередко среди наставников оказывались ученые, которые не смогли самостоятельно сдать экзамены, но хорошо представляли их структуру и процесс проведения изнутри.

Кроме того, в феодальном Китае существовало большое количество государственных и частных школ, где в основном учились дети богатых родителей. Воспитанники приходили на занятия с рассветом и уходили поздним вечером. Им запрещались какие-либо игры и развлечения. С собой позволялось приносить только учебную литературу и письменные принадлежности. Во время праздников украшать классы также было запрещено. Считалось, что это отвлекает от учебы и мешает сосредоточиться.

Благодаря экзаменам появилось новое блюдо

В Китае есть блюдо, которое якобы придумали из-за кэцзюй. По легенде, во время периода Цин в уезде Мэнцзы провинции Юньнань жил ученый, который сутками напролет готовился к предстоящему испытанию. Чтобы уединиться, он ушел на остров посреди озера, куда каждый день по мосту приходила его жена и приносила еду. Муж был настолько увлечен подготовкой, что надолго забывал про еду, а, опомнившись, был вынужден есть уже холодные блюда.

Жена придумала принести мужу котелок с лапшой и жирным куриным буольоном. Толстый слой жира не пропускал тепло, поэтому лапша не успевала остыть. Так появился популярный в провинции Юньнань суп с рисовой лапшой (过桥米线 guòqiáo mǐxiàn). Его название дословно переводится «лапша, переходящая через мост». Сегодня в суп также добавляют различные овощи и приправы.

Система кэцзюй не была идеальной

Несмотря на то, что создание экзаменационной системы изначально ставило перед собой благие намерения и было направлено на формирование профессионального чиновничьего аппарата, кэцзюй сталкивался с рядом серьезных недостатков. В первую очередь, экзамен был направлен на воспитание нравственных качеств участников и проверял знания классической литературы, а не научные или практические умения.

Экзамен не смог искоренить проблему коррупции и предвзятости в ходе оценивания кандидатов, а также требовал для подготовки больших финансовых затрат, которые позволить себе мог далеко не каждый. Тем не менее, именно эта система впоследствии стала использоваться в некоторых азиатских странах, таких как Япония или Вьетнам, а также оказала большое влияние на становление экзаменационной системы в Америке и Европе.

В Китае отголоски системы кэйцзюй сохраняются до сих пор. Как говорят сами китайцы, в стране действует меритократия. Это значит, что даже на самых низших выборных должностях происходит тщательный отбор кандидатов. На каждую должность назначаются самые достойные: учитывается уровень образования, членство в партии, проводятся различные конкурсные испытания и проверки.

По словам одного из жителей страны, если бы Дональд Трамп был китайцем, максимум, на какую должность он мог бы рассчитывать, — это глава деревни. И дело даже не в том, что в Китае отсутствуют прямые президентские выборы. Просто для того, чтобы занять такое высокое положение, необходимо начать с самых низов. Пройти все ступеньки карьерной лестницы и на каждой из них зарекомендовать себя лучшим специалистом. Например, губернатором провинции здесь может стать только бывший мэр, если возглавляемый им город вошел в список лучших городов с самыми высокими показателями.

Алена Смирнова

https://doi.org/10.30853/manuscript.2020.8.31

Шогенова Ляна Ахмедовна

Система государственных экзаменов для чиновников «кэцзюй» в императорском Китае

Цель исследования: выявить философские основания государственного управления в императорском Китае на примере отбора претендентов по особой экзаменационной системе; раскрыть принципы поступления на государственную службу, где ценились такие качества, как способность, эрудиция, а также лояльность по отношению к власти. Научная новизна исследования заключается в комплексном подходе к изучению особенностей функционирования и трансформации системы экзаменов «кэцзюй», а также в сравнении традиционного подхода к отбору государственных служащих и современных критериев отбора. Использование трудов отечественных и зарубежных авторов позволило подойти к данному вопросу с междисциплинарной точки зрения. В результате выявлены особенности формирования государственного аппарата, природа китайской власти и принципы ее существования.

Адрес статьи: www .gramota. net/m ate rials/9/2020/8/31.html

Источник Манускрипт

Тамбов: Грамота, 2020. Том 13. Выпуск 8. C. 170-174. ISSN 2618-9690.

Адрес журнала: www.gramota.net/editions/9.html

Содержание данного номера журнала: www .gramota.net/mate rials/9/2020/8/

© Издательство «Грамота»

Информация о возможности публикации статей в журнале размещена на Интернет сайте издательства: www.gramota.net Вопросы, связанные с публикациями научных материалов, редакция просит направлять на адрес: hist@gramota.net

https://doi.org/10.30853/manuscript.2020.8.31 Дата поступления рукописи: 27.04.2020

Цель исследования: выявить философские основания государственного управления в императорском Китае на примере отбора претендентов по особой экзаменационной системе; раскрыть принципы поступления на государственную службу, где ценились такие качества, как способность, эрудиция, а также лояльность по отношению к власти. Научная новизна исследования заключается в комплексном подходе к изучению особенностей функционирования и трансформации системы экзаменов «кэцзюй», а также в сравнении традиционного подхода к отбору государственных служащих и современных критериев отбора. Использование трудов отечественных и зарубежных авторов позволило подойти к данному вопросу с междисциплинарной точки зрения. В результате выявлены особенности формирования государственного аппарата, природа китайской власти и принципы её существования.

Ключевые слова и фразы: императорский Китай; экзаменационная система «кэцзюй»; государственная служба; учения Конфуция.

Шогенова Ляна Ахмедовна

Российская академия народного хозяйства и государственной службы при Президенте Российской Федерации, г. Москва shogenova. igsu@yandex. т

Система государственных экзаменов для чиновников «кэцзюй»

в императорском Китае

Актуальность темы исследования. Анализ экзаменационной системы позволяет понять не только особенности формирования государственного аппарата в Китае, но и отметить значимое место философии Конфуция в данном вопросе. Данный аспект гуманитарной истории Поднебесной важен также и с точки зрения понимания процессов, возникших в империи в эпоху колониализма, оказавшихся губительными для этой системы, несмотря на её многовековую историю. Для достижения цели исследования необходимо решить следующие задачи: рассмотреть историю возникновения и систему отбора государственных служащих в имперском Китае, изучить критерии отбора кандидатов, а также жесткие условия прохождения экзаменов, рассмотреть состав экзаменов, включающий обязательное знание философских трудов Конфуция, и влияние конфуцианства на управленческую мысль и образ «идеального» государственного служащего, а также провести сравнительный анализ традиционных и современных экзаменов в Китае в отношении конкурсного отбора на государственную службу.

Методы исследования. Использован сравнительно-исторический метод, позволяющий проследить элементы трансформации в системе, а также ее последующее влияние на отбор государственных служащих в современном Китае. Системный подход позволил объединить данные прикладного характера с междисциплинарным изучением данного вопроса — с точки зрения философии, менеджмента и истории.

Теоретическая база. Данная тема получила достаточно широкое освещение среди отечественных, а также зарубежных востоковедов. Исследователи подчеркивают уникальность системы, которая существовала в течение тринадцати веков и имела влияние на различные сферы китайского общества [6, с. 113]. Большой вклад в изучение концепта государственных экзаменов имперского Китая внесли отечественные востоковеды, посвятившие свои труды различным проблемам Китая, — Дмитрий Николаевич Воскресенский, Леонид Сергеевич Васильев, Вячеслав Михайлович Рыбаков и Нина Ефимовна Боревская.

Среди зарубежных исследователей, которые занимались вопросом изучения системы «кэцзюй», можно выделить следующих ученых: японского историка Миядзаки Итисада, английского китаиста Эндимиона Портера Уилкинсона и американского профессора китайских исследований Бенджамина Эльмана.

Практическая значимость данной статьи заключается в обобщении опыта отбора государственных служащих в традиционном Китае. Результаты работы могут быть использованы в исследованиях, посвященных данной тематике.

История возникновения государственного экзамена на чин

Китайская экзаменационная система кэцзюй представляет собой экзамен для чиновника (в императорском Китае), который проводился с 605 по 1905 гг. Данная система была установлена во времена царствования династии Суй и представляла собой конкурсный отбор чиновников посредством сдачи специальных тестов. Каждый, кто претендовал на то, чтобы стать чиновником, должен был сдать экзамен кэцзюй (44^ / keju), который являлся настоящим испытанием на прочность ввиду суровости условий, в которых он проводился.

Однако до введения «кэцзюй» во времена династии Хань (206 в. до н.э. — 220 в. до н.э.) действовала система «девяти рангов», создателем которой является Чэнь Цюнь. Ученые люди Средневековья находили государственное устройство ханьской державы примитивным и благоприятствовавшим коррупции [8, с. 73]. Чиновником мог стать только выходец из богатого и знатного общества, представителям низшего класса получить такую должность было довольно сложно.

Однако вскоре правители решили, что для укрепления центральной власти им нужны не столько богатые, сколько умные и лояльные придворные чиновники и военные [6, с. 113]. Именно тогда император решил начать отбор талантливых кадров по всей стране при помощи единой экзаменационной системы. Данная система, разработанная примерно 1400 лет назад, получила название государственного экзамена или «кэцзюй» и являлась весьма справедливым вариантом набора чиновников, предоставляя равные возможности для представителей разных сословий. Благодаря экзаменам государство смогло не только рассматривать уровень человеческих возможностей, но и определять благонадежность людей. Испытуемому необходимо было представить властям сведения следующего характера: возраст, место жительства, происхождение, сведения о трёх поколениях и описание внешности — последние два требования были введены маньчжурами. Учитывая, что экзамены были многоуровневыми, можно себе представить степень осведомлённости властей обо всех, кто подавал заявку на экзамен.

Д. Н. Воскресенский подчёркивает, что именно в факте воздействия государства на общество через экзамены и кроется одна из причин той исключительной заинтересованности, которую проявляли буквально все династии к экзаменам [2, с. 326].

Система имперских экзаменов в Китае была важным инструментом социальной мобильности в имперском Китае [3]. Результат экзамена не зависел от социального положения, а только от способностей испытуемого. Предоставление такой возможности для низших классов помогло распространить ключевые идеи конфуцианства, такие как правильное поведение, ритуалы, отношения, на все уровни китайского общества.

Что касается внутренней политики, система государственных экзаменов здесь играла роль «моста» между императорским домом и местными элитами, обеспечивала верность последних, а также служила гарантом равноправного представительства всех регионов Империи. В качестве предупреждения коррупции и возможного усиления местных клановых сообществ важным условием для предержащих экзамен на высокие звания была регулярная смена места службы.

Критерии отбора и условия прохождения конкурсных испытаний

К экзаменам допускались взрослые мужчины независимо от их финансового состояния и социального положения, на первых порах исключение составлял лишь класс торговцев. Женщины не могли быть допущены к государственной службе ввиду домашних обязанностей.

Для того чтобы стать чиновником высшего ранга, кандидаты должны были выдержать этапы письменных и устных испытаний по шести дисциплинам, таким как арифметика, каллиграфия, музыка, знание традиций, а также продемонстрировать навык стрельбы из лука и езду верхом.

Экзаменуемым вручали свиток с заданиями и закрывали в тесной келье на несколько дней. Во время заточения экзаменуемым запрещалось ходить, говорить и даже выходить в туалет. Требования экзаменов включали в себя хорошее знание традиционного китайского литературного языка и философских текстов.

Экзаменуемым предстояло написать несколько сочинений по книгам Конфуция и других классиков, причём одно из них — в стихах. Писать следовало красиво: навыки каллиграфического письма тоже оценивались. На экзаменах нужно было продемонстрировать знание «Пятикнижия», а позднее и «Четверокнижия»:

— «Канон Перемен» (кит. ШШ) считается одним из величайших и в то же время загадочных творений человека. С точки зрения породившей его китайской культуры (древнейшей из ныне существующих на земле) он представляет собой творение Сверхчеловека, запечатлевшего в особых символах и знаках тайну мироздания. «Канон перемен» — Книга книг, одно из духовных чудес света [6, с. 115];

— «Канон стихов» или «книга песен» (китЛ^Ш);

— «Канон о музыке» (с кит. «юэ-цзин» — канон, впоследствии утраченный и частично включенный в качестве отдельной главы в «Ли цзи», одно из основных произведений конфуцианского канона (кит.^^Е) -«Книга установлений», «Книга обрядов», «Трактат о правилах поведения», «Записки о нормах поведения»;

— «Канон документов» (кит. ^Ш);

— «Записи о ритуале» (кит.

— «Суждения и беседы» (кит.

— «Великое учение» (кит.

— «Срединное и неизменное» (кит. ФШ).

В XI веке китайский реформатор Ван Аньши (1021-1086 н.э.), правительственный реформатор, философ и известный литератор в династии Сун, предложил в качестве формы аттестации на государственных экзаменах использовать сочинение-рассуждение. В 1370 году первый император династии Мин Хунъу (Чжу Юаньчжан, 1328-1398, правил с 1368 года) утвердил его в качестве официальной формы [10].

В свое время в 21-летнем возрасте Ван сдал императорский экзамен на высшую ученую степень «цзинь ши» (кит. Й^, являлся высшей степенью в системе имперских экзаменов, он считался самым сложным) и затем служил местным чиновником в южных регионах до того, как стал советником при центральном правительстве в столице [12]. Тот период времени был, вероятно, самым наилучшим для династии Сун, поскольку за десятилетия мирного времени экономика, достигнув высокого уровня, стала процветать.

Экономика перешла от традиционного самостоятельного управления к более свободному, вошло в оборот использование первой в мире официальной бумажной валюты. Ван пытался претворить в жизнь реформы

под названием «Новые законы», которые затрагивали, прежде всего, налоговую систему, а также военную и гражданскую службы. Он пытался заставить правительство играть гораздо более активную роль в торговле путём создания фондов, предлагая займы под низкие проценты крестьянам, контролируя цены на товары и валюту, чтобы стимулировать экономику. С помощью этих реформ он пытался добиться процветания для всех слоев населения, а также укрепить финансовую систему и контроль центрального правительства. Однако его реформы нарушали интересы элитного общества и правящих классов, что рассматривалось как радикальное изменение целой правительственной системы, поддерживаемой консерваторами и бюрократами, но без каких-либо быстрых и существенных изменений.

Для более эффективного и рационального осуществления своих «Новых законов» Ван внес коррективы в существующий императорский экзамен на государственную службу. Темы из классики Конфуция и поэзии сменились на более практические предметы, такие как обсуждение политики, также большое внимание уделялось изучению медицины [Ibidem].

Ван Анши ушел на пенсию в 1076 году, после понижения в должности и неудач в реализации своих «Новых законов». По мнению американского историка и синолога Питера Кис Бола, профессора Гарвардского университета, Ван Аньши «остается примером того, чего не следует делать правителю» [Ibidem].

В XV веке появилось сочинение ba gu wen), состоявшее из восьми частей, со строго регламенти-

рованной формой и знаками, которые не должны были превышать 700 символов, и написанное архаическим языком гувэнь (кит.

Структура сочинения включала в себя:

— вступление (кит. Ж®досл. «удар по теме») — два предложения прозой, вводящие в тему;

— развитие и прояснение темы (кит. ^Шдосл. «собирать тему») — второй раздел эссе, пять предложений прозы, уточняющих тему;

— общее рассуждение (кит. ЁЩдосл. «начало рассуждения») — прозаический текст: раскрытие темы с общим рассуждением [6, с. 118];

— зачин рассуждения (кит. qigu досл. «первоначальный раздел») — несколько параллельных рассуждений, определенных экзаменационным заданием, развивающих первоначальный аргумент. Параллельные предложения должны были иметь общую структуру и передавать разными словами близкие значения. Экзаменуемый должен был продемонстрировать искусство подбирать синонимы [Там же];

— центральное рассуждение (кит.ФШ, zhong gu досл. «центральная часть рассуждения») в свободном изложении;

— завершающее рассуждение (кит. ^Ш, hou gU досл. «задний раздел») — окончание рассуждения;

— увязка рассуждений (кит.ЖШ, shu gU досл. «связывающий раздел») — последний аргумент, без ограничения количества предложений;

— большая увязка подхода к теме и экспозиции темы (кит. ^^и, dajie досл. «большой узел») — итог сочинения, заключительные замечания, написанные прозой с возможностью самовыражения и творчества [7].

При малейшем намеке на списывание как экзаменуемым, так и проверяющим грозило наказание в виде тюремного срока или даже смертной казни. Авторство работ было зашифровано в целях того, чтобы проверяющий не смог узнать почерк экзаменуемого. У входа в экзаменационную комнату стояла пара солдат, которые отвечали за идентификацию личности экзаменуемого с документами и описанием личности, представленными в характеристике при подаче, — рост, наличие бороды, цвет кожи, общие черты лица и т.д. [15].

Система экзаменов традиционно подразделялась на несколько этапов: местный, провинциальный и столичный. Местный экзамен устраивался ежегодно, а тех, кому посчастливилось его сдать, называли «сюцай» (кит. то есть талантливыми людьми. Как отмечает А. А. Маслов, бытовало также и такое понятие,

как «бедный сюцай», то есть ученый, который так и не получил должность, предварительно потратив немало денег на образование [5].

«Сюцай» проходили во второй тур и пробовали свои силы в провинциальном экзамене, который проводился раз в три года. В случае если они могли выдержать и этот экзамен, то они допускались к столичному экзамену. Последним этапом на пути к карьере чиновника высокого ранга был дворцовый экзамен, который проводился под наблюдением самого императора. В зависимости от результатов дворцового экзамена кандидатов назначали на ту или иную должность при дворе.

Те, кто провалил дворцовый экзамен, но прошел все предыдущие уровни, также получали почетные звания, которые помогали им занять престижную должность в других учреждениях, например, в школе или местном управлении.

Китайская экзаменационная система оказалась популярной во многих странах региона. Корея и Вьетнам пользовались такой же системой набора чиновников. В Японии же такой опыт не получил реального распространения в результате зарождения самурайства [10, p. 117].

Англия официально внедрила такую систему в 1870 году, однако здесь ряд вакансий был ограничен, а тем, кто сдал экзамен, работа не всегда гарантировалась. Особое внимание также уделялось биографии потенциального кандидата, изучались медицинские записи, чтобы убедиться, что претендующий новобранец не болен [14].

Отсылки к экзаменационной системе «кэцзюй» в современных экзаменах на государственную службу Несмотря на то, что в 1905 году китайская экзаменационная система была отменена (просуществовала 1300 лет), её влияние на китайскую культуру прослеживается до сих пор.

Во-первых, отмена данной системы дала толчок к развитию женского образования, так как при старой системе женщины не были допущены к конкурсной основе. Так, во времена Цинской империи принимается «Устав о женских начальных школах» [16].

Во-вторых, отмена традиционной системы «кэцзюй» открыла дорогу молодым людям, желающим получить образование за границей, что в свою очередь послужило зарождению новых заметных политических деятелей, которые содействовали распространению научных знаний.

Интересен тот факт, что даже в современном Китае экзаменационный опыт тестирования чиновников сохранил свое значение при назначении на должность. Однако не обошлось без изменений, количество экзаменов сократили до одного. Такой экзамен носит название «го као» (кит. 0%), где только у одного человека из 60-ти получается попасть на желаемую позицию, а именно в государственный сектор [13].

Кандидаты сдают письменный экзамен по таким темам, как китайская политика, международные отношения, язык и логика. Лица, претендующие на должность в области финансов, должны сдать экзамен на профессиональную квалификацию.

Интересно провести параллель с отечественной практикой подготовки кадров и проведения аттестации и проверки профессиональных компетенций и личностных характеристик в России [16]. Как известно, в нашей стране в последние годы усиленно ведется политика повышения эффективности сотрудников, а именно чиновников. Перед тем как приступить к должности, управленцам необходимо пройти специальное углубленное изучение дисциплин, связанных с получением компетенций в области государственного и муниципального управления, сдать экзамены на знание современных управленческих практик, причем только в тех вузах, которые имеют аккредитованные образовательные программы данного профиля.

Во всех субъектах Российской Федерации проводится открытый конкурс «Лидеры России» для руководителей нового поколения, который считается эффективным социальным лифтом для государственного аппарата. Чтобы пройти конкурсный отбор, нужно выдержать серию дистанционных тестов, а в полуфинале и в финале, в свою очередь, — ряд сложнейших испытаний, что, по мнению историков, очень схоже с системой отбора еще в императорском Китае.

Также ведется работа по созданию кадрового резерва для специалистов. К примеру, если рассматривать региональный опыт, в Кабардино-Балкарской Республике в 2018 году был проведен специальный конкурс «Новая высота» с целью выявления, развития и поддержки новых специалистов, развития управленческих качеств и повышения уровня подготовки кадрового потенциала Республики, органов местного самоуправления и республиканских государственных учреждений. Основные требования, предъявляемые к претендентам, участвующим в конкурсе на замещение вакантных должностей, касаются не только понимания философии управления, правовых механизмов регулирования общественных отношений, но и этики поведения и личных качеств будущего чиновника.

Таким образом, мы приходим к следующим выводам. Экзаменационная система «кэцзюй» представляла собой конкурсный отбор чиновников посредством сдачи специальных тестов в императорском Китае. Данная система позволила проводить широкий конкурный отбор среди желающих поступить на государственную службу, в том числе и для выходцев из низших слоев. Несмотря на то, что структура испытаний претерпевала некоторые изменения и коррективы на протяжении своего существования, базисной основой всегда являлось хорошее знание философских трудов Конфуция. Главная причина — Конфуцианство всегда ставило во главе своих центральных проблем вопросы отношений между правителем и поданными, большое внимание уделялось тому, каким должен быть руководитель, какие качества ему должны быть присущи. Ведь именно Конфуций выдвинул в свое время идеал правильного государственного устройства, где власть принадлежит «ученым», совмещающим в себе три свойства — философское, литераторское и чиновническое.

Конечно, нельзя проводить прямой аналогии между разбираемой экзаменационной системой, существовавшей в Китае, и современными моделями конкурсного отбора на гражданскую государственную службу, тем не менее опыт даже когда-то упраздненной китайской системы имперских экзаменов, будучи локальным опытом, изучался и принимался во внимание при разработке собственных подходов в других странах в целях эффективности отбора в ряды государственных служащих. Модернизируется система контрольных форм, включаются в инструментарий новые информационные технологии, тем не менее сохраняются требования к аналитическим способностям, логике и аргументированности построения письменной и устной речи, поскольку весь этот инструментарий должен работать на укрепление государственности как высшей цели империи.

Список источников

1. Боревская Н. Е. Система императорских экзаменов в Китае [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://portalus.ru/modules/ shkola/rus_readme.php?subaction=showfull&id=1193921712&archive=1194448667&start_from=&ucat=& (дата обращения: 09.01.2020).

2. Воскресенский Д. Н. Человек в системе государственных экзаменов (тема и литературный герой в китайской прозе XVH-XVHI вв.) // История и культура Китая: сб. памяти акад. В. П. Васильева / под ред. Л. С. Васильева. М.: Наука, 1974. С. 325-361.

3. Жильцов В. И. Оценка эффективности в системе государственной службы. М.: Проспект, 2018. 96 с.

4. Малявин В. В. Империя ученых. М.: Европа, 2007. 384 с.

5. Маслов А. А. Россия позаимствовала систему тестов для чиновников у Древнего Китая [Электронный ресурс]: интервью // Взгляд. Деловая газета. 2019. 02 апреля. URL: https://vz.ru/poHtics/2019/4/2/971276.html (дата обращения: 03.06.2020).

6. Смирнова Н. В. Тема государственных экзаменов (кэцзюй) в исследованиях и переводах Дмитрия Николаевича Воскресенского // Вестник Тверского государственного университета. Серия «История». 2019. № 1 (49). С. 113-124.

7. Федотова Л. Ф. Школы древнекитайской философии // Федотова Л. Ф. Философия Древнего Востока. М.: Спут-ник+, 2015. С. 70-73.

8. Цзинь Шэнь. Кэцзюй — система государственных экзаменов в императорском Китае как фактор формирования национального характера и менталитета // Мы говорим на одном языке: материалы докладов и сообщений VI Меж-дунар. студ. конф. СПб.: Изд-во РГГМУ, 2018. С. 72-80.

9. Шогенова Л. А. Развитие межкультурных российско-китайских связей // Межкультурное взаимодействие России и Китая: глобальное и локальное измерение: колл. монография / отв. ред.: А. Н. Чумаков, Ли Хэй. М.: Проспект, 2019. С. 178-191.

10. A Research Agenda for Public Administration / ed. by A. Massey. Edward Elgar Publishing, Ltd., 2019. 256 p.

11. Ichisada Miyazaki. China’s Examination Hell: The Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China. Revised edition. N. Y. — Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1976. 145 p.

12. Wang Anshi: The reformer beaten by the mandarins [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-19962432 (дата обращения: 03.02.2020).

13. Wendy Wu. China’s civil service exam attracts 1.4 million applicants with eyes on the prize of an «iron ice bowl» job // South China Morning Post. 2019. 24 November.

14. Willis R. Testing times: A history of civil service exams [Электронный ресурс] / University of London. URL: https://www.civilserviceworld.com/articles/feature/testing-1imes-history-civil-service-exams (дата обращения: 05.04.2020).

15. (Процесс сдачи императорских экзаменов, «Цзинь ши», регистрация и правила в экзаменационных комнатах) [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.360kuai. com/ (дата обращения: 30.04.2020).

16. тт°щтжтшшжшщщтжшт // 2010. шЙ. ®9з-9би

(Лю Шаочунь. Кэцзюй. Развитие нового образования после упразднения государственных экзаменов и воссоздание аттестационной системы // Журнал Шэньянского педагогического университета. Общественные науки. 2010. № 6. С. 93-96).

Civil Service Examination System (Keju) in Imperial China

Shogenova Lyana Akhmedovna

Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, Moscow

shogenova. igsu@yandex. ru

The research objectives are as follows: to reveal philosophical foundations of the state administration system in Imperial China by the example of the civil service exam; to discover principles for choosing candidates for civil service positions requiring such qualities as competence, erudition and loyalty towards the ruling power. Scientific originality of the paper lies in the fact that the author suggests a comprehensive approach to studying the functioning and evolution of the civil service examination system (keju) and compares the traditional approach to civil servants appointment and present-day selection criteria. The study is based on works of domestic and foreign sinologists and has interdisciplinary nature. The research findings are as follows: the author identifies specificity of the Chinese state apparatus formation, reveals nature and principles of the Chinese power.

Key words and phrases: Imperial China; civil service examination system (keju); civil service; Confucius teachings.

iНе можете найти то, что вам нужно? Попробуйте сервис подбора литературы.

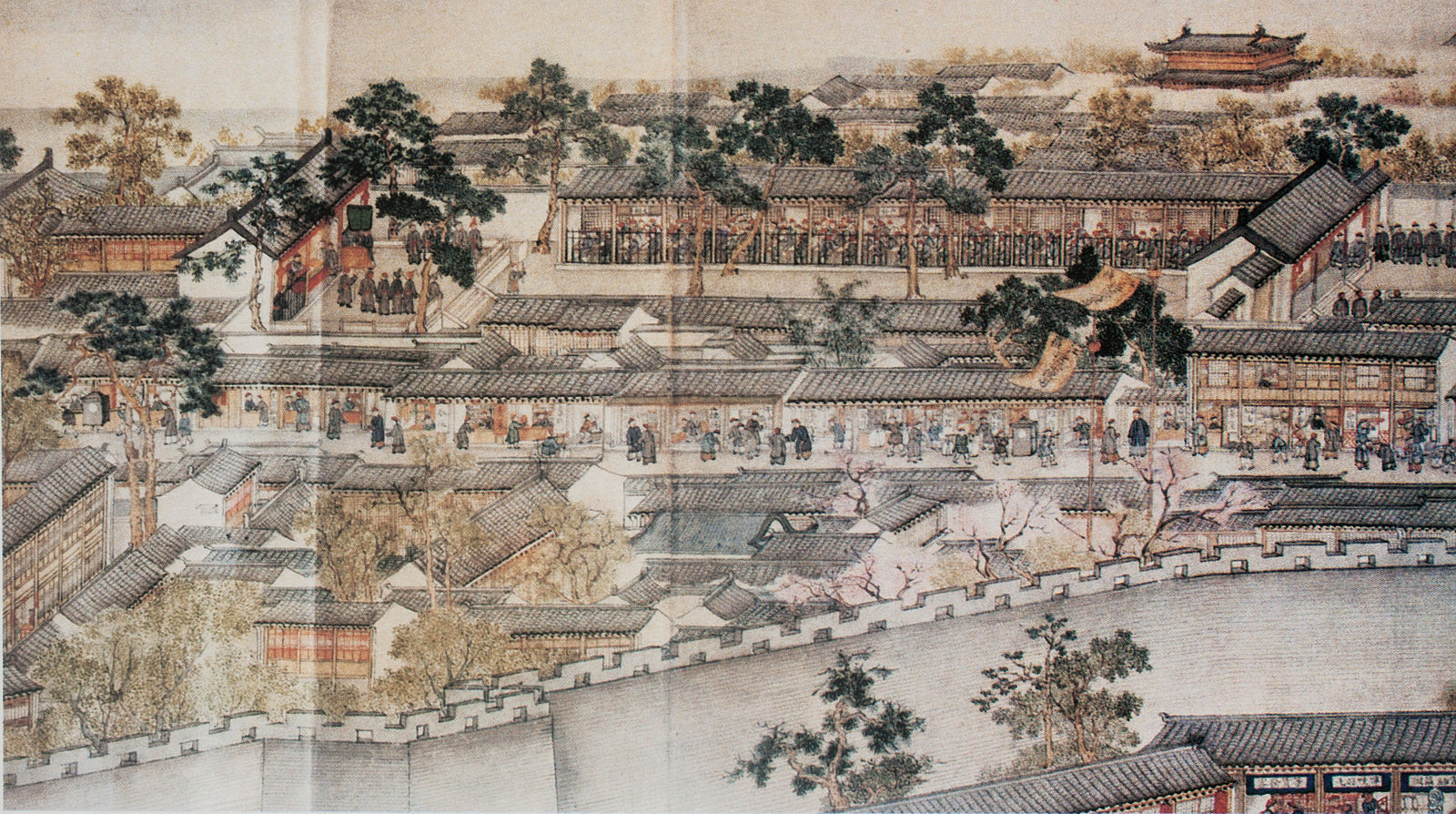

Candidates gathering around the wall where the results are posted. This announcement was known as «releasing the roll» (放榜). (c. 1540, by Qiu Ying)

| Imperial examination | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«Imperial examinations» in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 科舉 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 科举 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | kējǔ | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | khoa bảng khoa cử |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 科榜 科舉 |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 과거 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 科擧 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | かきょ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 科擧 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 科挙 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡤᡳᡡ ᡰ᠊ᡳᠨ ᠰᡳᠮᠨᡝᡵᡝ |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Möllendorff | giū žin simnere |

The imperial examination (Chinese: 科舉; pinyin: kējǔ; lit. «subject recommendation») was a civil-service examination system in Imperial China administered for the purpose of selecting candidates for the state bureaucracy. The concept of choosing bureaucrats by merit rather than by birth started early in Chinese history, but using written examinations as a tool of selection started in earnest during the Sui dynasty[1][2] (581–618) then into the Tang dynasty of 618–907. The system became dominant during the Song dynasty (960–1279) and lasted for almost a millennium until its abolition during the late Qing dynasty reforms in 1905. Aspects of the imperial examination still exist for entry into the civil service of contemporary China, in both the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC).

The exams served to ensure a common knowledge of writing, Chinese classics, and literary style among state officials. This common culture helped to unify the empire, and the ideal of achievement by merit gave legitimacy to imperial rule. The examination system played a significant role in tempering the power of hereditary aristocracy and military authority, and in the rise of a gentry class of scholar-bureaucrats.

Starting with the Song dynasty, the imperial examination system became a more formal system and developed into a roughly three-tiered ladder from local to provincial to court exams. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), authorities narrowed the content down to mostly texts on Neo-Confucian orthodoxy; the highest degree, the jinshi (Chinese: 進士), became essential for the highest offices. On the other hand, holders of the basic degree, the shengyuan (生員), became vastly oversupplied, resulting in holders who could not hope for office. Wealthy families, especially from the merchant class, could opt into the system by educating their sons or by purchasing degrees. During the late 19th century, some critics within Qing China blamed the examination system for stifling scientific and technical knowledge, and urged for some reforms. At the time, China had about one civil licentiate per 1000 people. Due to the stringent requirements, there was only a 1% passing rate among the two or three million annual applicants who took the exams.[3]

The Chinese examination system has had a profound influence in the development of modern civil service administrative functions in other countries.[4] These include analogous structures that have existed in Japan,[5] Korea, the Ryukyu Kingdom, and Vietnam. In addition to Asia, reports by European missionaries and diplomats introduced the Chinese examination system to the Western world and encouraged France, Germany as well as the British East India Company (EIC) to use similar methods to select prospective employees. Seeing its initial success within the EIC, the British government adopted a similar testing system for screening civil servants across the board throughout the United Kingdom in 1855. The United States would also establish such programs for certain government jobs after 1883.

General history[edit]

Tests of skill such as archery contests have existed since the Zhou dynasty (or, more mythologically, Yao).[6] The Confucian characteristic of the later imperial exams was largely due to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han during the Han dynasty. Although some examinations did exist from the Han to the Sui dynasty, they did not offer an official avenue to government appointment, the majority of which were filled through recommendations based on qualities such as social status, morals, and ability.

The bureaucratic imperial examinations as a concept has its origins in the year 605 during the short-lived Sui dynasty. Its successor, the Tang dynasty, implemented imperial examinations on a relatively small scale until the examination system was extensively expanded during the reign of Wu Zetian.[7] Included in the expanded examination system was a military exam, but the military exam never had a significant impact on the Chinese officer corps and military degrees were seen as inferior to their civil counterpart. The exact nature of Wu’s influence on the examination system is still a matter of scholarly debate.

During the Song dynasty the emperors expanded both examinations and the government school system, in part to counter the influence of military aristocrats, increasing the number of degree holders to more than four to five times that of the Tang. From the Song dynasty onward, the examinations played the primary role in selecting scholar-officials, who formed the literati elite of society. However the examinations co-existed with other forms of recruitment such as direct appointments for the ruling family, nominations, quotas, clerical promotions, sale of official titles, and special procedures for eunuchs. The regular higher level degree examination cycle was decreed in 1067 to be three years but this triennial cycle only existed in nominal terms. In practice both before and after this, the examinations were irregularly implemented for significant periods of time: thus, the calculated statistical averages for the number of degrees conferred annually should be understood in this context. The jinshi exams were not a yearly event and should not be considered so; the annual average figures are a necessary artifact of quantitative analysis.[8][incomplete short citation] The operations of the examination system were part of the imperial record keeping system, and the date of receiving the jinshi degree is often a key biographical datum: sometimes the date of achieving jinshi is the only firm date known for even some of the most historically prominent persons in Chinese history.

A brief interruption to the examinations occurred at the beginning of the Yuan dynasty in the 13th century, but was later brought back with regional quotas which favored the Mongols and disadvantaged Southern Chinese. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the system contributed to the narrow and focused nature of intellectual life and enhanced the autocratic power of the emperor. The system continued with some modifications until its abolition in 1905 during the last years of the Qing dynasty. The modern examination system for selecting civil servants also indirectly evolved from the imperial one.[9]

| Dynasty | Exams held | Jinshi graduates |

|---|---|---|

| Tang (618–907) | 6,504 | |

| Song (960–1279) | 118 | 38,517 |

| Yuan (1271–1368) | 16 | 1,136 |

| Ming (1368–1644) | 89 | 24,536 |

| Qing (1636–1912) | 112 | 26,622 |

Precursors[edit]

Chinese Examination Cells at the South River School (Nanjiangxue) Nanjing (China). This structure prevents cheating in exams.

Han dynasty[edit]

Candidates for offices recommended by the prefect of a prefecture were examined by the Ministry of Rites and then presented to the emperor. Some candidates for clerical positions would be given a test to determine whether they could memorize nine thousand Chinese characters.[10] The tests administered during the Han dynasty did not offer formal entry into government posts. Recruitment and appointment in the Han dynasty were primarily through recommendations by aristocrats and local officials. Recommended individuals were also primarily aristocrats. In theory, recommendations were based on a combination of reputation and ability but it is not certain how well this worked in practice. Oral examinations on policy issues were sometimes conducted personally by the emperor himself during Western Han times.[11]

In 165 BC Emperor Wen of Han introduced recruitment to the civil service through examinations. However, these did not heavily emphasize Confucian material. Previously, potential officials never sat for any sort of academic examinations.[12]

Emperor Wu of Han’s early reign saw the creation of a series of posts for academicians in 136 BC.[13] Ardently promoted by Dong Zhongshu, the Taixue and Imperial examination came into existence by recommendation of Gongsun Hong, chancellor under Wu.[14] Officials would select candidates to take part in an examination of the Confucian classics, from which Emperor Wu would select officials to serve by his side.[15] Gongsun intended for the Taixue’s graduates to become imperial officials but they usually only started off as clerks and attendants,[16] and mastery of only one canonical text was required upon its founding, changing to all five in the Eastern Han.[17][18] Starting with only 50 students, Emperor Zhao expanded it to 100, Emperor Xuan to 200, and Emperor Yuan to 1000.[19]

While the examinations expanded under the Han, the number of graduates who went on to hold office were few. The examinations did not offer a formal route to commissioned office and the primary path to office remained through recommendations. Though connections and recommendations remained more meaningful than the exam, the initiation of the examination system by Emperor Wu was crucial for the Confucian nature of later imperial examinations. During the Han dynasty, these examinations were primarily used for the purpose of classifying candidates who had been specifically recommended. Even during the Tang dynasty the quantity of placements into government service through the examination system only averaged about nine persons per year, with the known maximum being less than 25 in any given year.[15]

Three Kingdoms[edit]

The first standardized method of recruitment in Chinese history was introduced during the Three Kingdoms period in the Kingdom of Wei. It was called the nine-rank system. In the nine-rank system, each office was given a rank from highest to lowest in descending order from one to nine. Imperial officials were responsible for assessing the quality of the talents recommended by local elites. The criteria for recruitment included qualities such as morals and social status, which in practice meant that influential families monopolized all high ranking posts while men of poorer means filled the lower ranks.[20][21]

The local zhongzheng (lit. central and impartial) officials assessed the status of households or families in nine categories; only the sons of the fifth categories and above were entitled to offices. The method obviously contradicted the ideal of meritocracy. It was, however, convenient in a time of constant wars among the various contending states, all of them relying on an aristocratic political and social structure. For nearly three hundred years, noble young men were afforded government higher education in the Imperial Academy and carefully prepared for public service. The Jiupin guanren fa was closely related to this kind of educational practice and only began to decline after the second half of the sixth century.[22]

— Thomas H. C. Lee

History by dynasty[edit]

Sui dynasty (581–618)[edit]

The Sui dynasty continued the tradition of recruitment through recommendation but modified it in 587 with the requirement for every prefecture (fu) to supply three scholars a year. In 599, all capital officials of rank five and above were required to make nominations for consideration in several categories.[20]

During the Sui dynasty, examinations for «classicists» (mingjing ke) and «cultivated talents» (xiucai ke) were introduced. Classicists were tested on the Confucian canon, which was considered an easy task at the time, so those who passed were awarded posts in the lower rungs of officialdom. Cultivated talents were tested on matters of statecraft as well as the Confucian canon. In AD 607, Emperor Yang of Sui established a new category of examinations for the «presented scholar» (jinshike 进士科). These three categories of examination were the origins of the imperial examination system that would last until 1905. Consequently, the year 607 is also considered by many to be the real beginning of the imperial examination system. The Sui dynasty was itself short lived however and the system was not developed further until much later.[21]

The imperial examinations did not significantly shift recruitment selection in practice during the Sui dynasty. Schools at the capital still produced students for appointment. Inheritance of official status was also still practiced. Men of the merchant and artisan classes were still barred from officialdom. However the reign of Emperor Wen of Sui did see much greater expansion of government authority over officials. Under Emperor Wen (r. 581–604), all officials down to the district level had to be appointed by the Department of State Affairs in the capital and were subjected to annual merit rating evaluations. Regional Inspectors and District Magistrates had to be transferred every three years and their subordinates every four years. They were not allowed to bring their parents or adult children with them upon reassignment of territorial administration. The Sui did not establish any hereditary kingdoms or marquisates (hóu) of the Han sort. To compensate, nobles were given substantial stipends and staff. Aristocratic officials were ranked based on their pedigree with distinctions such as «high expectations», «pure», and «impure» so that they could be awarded offices appropriately.[23]

Tang dynasty (618–907)[edit]

The Tang dynasty and the Zhou interregnum of Empress Wu (Wu Zetian) expanded examinations beyond the basic process of qualifying candidates based on questions of policy matters followed by an interview.[24] Oral interviews as part of the selection process were theoretically supposed to be an unbiased process, but in practice favored candidates from elite clans based in the capitals of Chang’an and Luoyang (speakers of solely non-elite dialects could not succeed).[25]

Under the Tang, six categories of regular civil-service examinations were organized by the Department of State Affairs and held by the Ministry of Rites: cultivated talents, classicists, presented scholars, legal experts, writing experts, and arithmetic experts. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang also added categories for Daoism and apprentices. The hardest of these examination categories, the presented scholar jinshi degree, became more prominent over time until it superseded all other examinations. By the late Tang the jinshi degree became a prerequisite for appointment into higher offices. Appointments by recommendation were also required to take examinations.[20]

The examinations were carried out in the first lunar month. After the results were completed, the list of results was submitted to the Grand Chancellor, who had the right to alter the results. Sometimes the list was also submitted to the Secretariat-Chancellery for additional inspection. The emperor could also announce a repeat of the exam. The list of results was then published in the second lunar month.[21]

Classicists were tested by being presented phrases from the classic texts. Then they had to write the whole paragraph to complete the phrase. If the examinee was able to correctly answer five of ten questions, they passed. This was considered such an easy task that a 30-year-old candidate was said to be old for a classicist examinee, but young to be a jinshi. An oral version of the classicist examination known as moyi also existed but consisted of 100 questions rather than just ten. In contrast, the jinshi examination not only tested the Confucian classics, but also history, proficiency in compiling official documents, inscriptions, discursive treatises, memorials, and poems and rhapsodies. Because the number of jinshi graduates were so low they acquired great social standing in society. The judicial, arithmetic, and clerical examinations were also held but these graduates only qualified for their specific agencies.[21]

Candidates who passed the exam were not automatically granted office. They still had to pass a quality evaluation by the Ministry of Rites, after which they were allowed to wear official robes.[21]

Wu Zhou dynasty[edit]

Wu Zetian’s reign was a pivotal moment for the imperial examination system.[15] The reason for this was because up until that point, the Tang rulers had all been male members of the Li family. Wu Zetian, who officially took the title of emperor in 690, was a woman outside the Li family who needed an alternative base of power. Reform of the imperial examinations featured prominently in her plan to create a new class of elite bureaucrats derived from humbler origins. Both the palace and military examinations were created under Wu Zetian.[21]

In 655, Wu Zetian graduated 44 candidates with the jìnshì degree (進士), and during one seven-year period the annual average of exam takers graduated with a jinshi degree was greater than 58 persons per year. Wu lavished favors on the newly graduated jinshi degree-holders, increasing the prestige associated with this path of attaining a government career, and clearly began a process of opening up opportunities to success for a wider population pool, including inhabitants of China’s less prestigious southeast area.[15] Wu Zetian’s government further expanded the civil service examination system by allowing certain commoners and gentry previously disqualified by their non-elite backgrounds to take the tests.[26] Most of the Li family supporters were located to the northwest, particularly around the capital city of Chang’an. Wu’s progressive accumulation of political power through enhancement of the examination system involved attaining the allegiance of previously under-represented regions, alleviating frustrations of the literati, and encouraging education in various locales so even people in the remote corners of the empire would study to pass the imperial exams. These degree holders would then become a new nucleus of elite bureaucrats around which the government could center itself.[27]

In 681, a fill in the blank test based on knowledge of the Confucian classics was introduced.[28]

Examples of officials whom she recruited through her reformed examination system include Zhang Yue, Li Jiao, and Shen Quanqi.[29]

Despite the rise in importance of the examination system, the Tang society was still heavily influenced by aristocratic ideals, and it was only after the ninth century that the situation changed. As a result, it was common for candidates to visit examiners before the examinations in order to win approval. The aristocratic influence declined after the ninth century, when the examination degree holders also increased in numbers. They now began to play a more decisive role in the Court. At the same time, a quota system was established which could enhance the equitable representation, geographically, of successful candidates.[30]

— Thomas H. C. Lee

From 702 onward, the names of examinees were hidden to prevent examiners from knowing who was tested. Prior to this, it was even a custom for candidates to present their examiner with their own literary works in order to impress him.[21]

Tang restoration[edit]

Sometime between 730 and 740, after the Tang restoration, a section requiring the composition of original poetry (including both shi and fu) was added to the tests, with rather specific set requirements: this was for the jinshi degree, as well as certain other tests. The less-esteemed examinations tested for skills such as mathematics, law, and calligraphy. The success rate on these tests of knowledge on the classics was between 10 and 20 percent, but for the thousand or more candidates going for a jinshi degree each year in which it was offered, the success rate for the examinees was only between 1 and 2 percent: a total of 6504 jinshi were created during course of the Tang dynasty (an average of only about 23 jinshi awarded per year).[28] After 755, up to 15 percent of civil service officials were recruited through the examinations.[31]

During the early years of the Tang restoration, the following emperors expanded on Wu’s policies since they found them politically useful, and the annual averages of degrees conferred continued to rise. This led to the formation of new court factions consisting of examiners and their graduates. With the upheavals which later developed and the disintegration of the Tang empire into the «Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period», the examination system gave ground to other traditional routes to government positions and favoritism in grading reduced the opportunities of examinees who lacked political patronage.[27] Ironically this period of fragmentation resulted in the utter destruction of old networks established by elite families that had ruled China throughout its various dynasties since its conception. With the disappearance of the old aristocracy, Wu’s system of bureaucrat recruitment once more became the dominant model in China, and eventually coalesced into the class of nonhereditary elites who would become known to the West as «mandarins», in reference to Mandarin, the dialect of Chinese employed in the imperial court.[32]

Song dynasty (960–1279)[edit]

The emperor receives a candidate during the Palace Examination. Song dynasty.

In the Song dynasty (960–1279) the imperial examinations became the primary method of recruitment for official posts. More than a hundred palace examinations were held during the dynasty, resulting in a greater number of jinshi degrees rewarded.[20] The examinations were opened to adult Chinese males, with some restrictions, including even individuals from the occupied northern territories of the Liao and Jin dynasties.[33] Figures given for the number of examinees record 70–80,000 in 1088 and 79,000 at the turn of the 12th century.[34] In the mid-11th century, between 5,000 and 10,000 took the metropolitan examinations in a given year.[35] By the mid-12th century, 100,000 candidates registered for the prefectural examinations each year, and by the mid-13th century, more than 400,000.[36] The number of active jinshi degree holders ranged from 5,000 to 10,000 between the 11th and 13th centuries, representing 7,085 of 18,700 posts in 1046 and 8,260 of 38,870 posts in 1213.[35] Statistics indicate that the Song imperial government degree-awards eventually more than doubled the highest annual averages of those awarded during the Tang dynasty, with 200 or more per year on average being common, and at times reaching a per annum figure of almost 240.[27]

The examination hierarchy was formally divided into prefectural, metropolitan, and palace examinations. The prefectural examination was held on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. Graduates of the prefectural examination were then sent to the capital for metropolitan examination, which took place in Spring, but had no fixed date. Graduates of the metropolitan examination were then sent to the palace examination.[21]

Many individuals of low social status were able to rise to political prominence through success in the imperial examination. According to studies of degree-holders in the years 1148 and 1256, approximately 57 percent originated from families without a father, grandfather, or great-grandfather who had held official rank.[37] However most did have some sort of relative in the bureaucracy.[38] Prominent officials who went through the imperial examinations include Wang Anshi, who proposed reforms to make the exams more practical, and Zhu Xi (1130–1200), whose interpretations of the Four Classics became the orthodox Neo-Confucianism which dominated later dynasties. Two other prominent successful entries into politics through the examination system were Su Shi (1037–1101) and his brother Su Zhe (1039–1112): both of whom became political opponents of Wang Anshi. The process of studying for the examination tended to be time-consuming and costly, requiring time to spare and tutors. Most of the candidates came from the numerically small but relatively wealthy land-owning scholar-official class.[39]

Since 937, by the decision of the Emperor Taizu of Song, the palace examination was supervised by the emperor himself. In 992, the practice of anonymous submission of papers during the palace examination was introduced; it was spread to the departmental examinations in 1007, and to the prefectural level in 1032. From 1037 on, it was forbidden for examiners to supervise examinations in their home prefecture. Examiners and high officials were also forbidden from contacting each other prior to the exams. The practice of recopying papers in order to prevent revealing the candidate’s calligraphy was introduced at the capital and departmental level in 1015, and in the prefectures in 1037.[40]

In 1009, Emperor Zhenzong of Song (r. 997–1022) introduced quotas on degrees awarded. In 1090, only 40 degrees were awarded to 3,000 candidates in Fuzhou, which meant only one degree would be awarded for every 75 candidates. The quota system became even more stringent in the 13th century when only one percent of candidates were allowed to pass the prefectural examination. Even graduates of the lowest tier of examinations represented an elite class.[36]

In 1071, Emperor Shenzong of Song (r. 1067–1085) abolished the classicist as well as various other examinations on law and arithmetics. The jinshi examination became the primary gateway to officialdom. Judicial and classicist examinations were revived shortly after. However the judicial examination was classified as a special examination and not many people took the classicist examination. The oral version of the classicist exam was abolished. Other special examinations for household and family member of officials, Minister of Personnel, and subjects such as history as applied to current affairs (shiwu ce, Policy Questions), translation, and judicial matters were also administered by the state. Policy Questions became an essential part of following examinations. An exam called the cewen which focused on contemporary matters such as politics, economics, and military affairs was introduced.[21][41]

The Song also saw the introduction of a new examination essay, that of jing yi; (exposition on the meaning of the Classics). This required candidates to compose a logically coherent essay by juxtaposing quotations from the Classics or sentences of similar meaning to certain passages. This reflected the stress the Song placed on creative understanding of the Classics. It would eventually develop into the so-called ‘eight-legged essays’ (bagu wen) that gave the defining character to the Ming and Qing examinations.[42]

— Thomas H. C. Lee

Various reforms or attempts to reform the examination system were made during the Song dynasty by individuals such as Fan Zhongyan, Zhu Xi, and by Wang Anshi. Wang and Zhu successfully argued that poems and rhapsodies should be excluded from the examinations because they were of no use to administration or cultivation of virtue. The poetry section of the examination was removed in the 1060s. Fan’s memorial to the throne initiated a process which lead to major educational reform through the establishment of a comprehensive public school system.[43][21]

Liao dynasty (916–1125)[edit]

The Khitans who ruled the Liao dynasty only held imperial examinations for regions with large Han populations. The Liao examinations focused on lyric-meter poetry and rhapsodies. The Khitans themselves did not take the exams until 1115 when it became an acceptable avenue for advancing their careers.[44]

Jin dynasty (1115–1234)[edit]

The Jurchens of the Jin dynasty held two separate examinations to accommodate their former Liao and Song subjects. In the north examinations focused on lyric-meter poetry and rhapsodies while in the south, Confucian Classics were tested. During the reign of Emperor Xizong of Jin (r. 1135–1150), the contents of both examinations were unified and examinees were tested on both genres. Emperor Zhangzong of Jin (r. 1189–1208) abolished the prefectural examinations. Emperor Shizong of Jin (r. 1161–1189) created the first examination conducted in the Jurchen language, with a focus on political writings and poetry. Graduates of the Jurchen examination were called «treatise graduates» (celun jinshi) to distinguish them from the regular Chinese jinshi.[21]

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)[edit]

Imperial examinations were ceased for a time with the defeat of the Song in 1279 by Kublai Khan and his Yuan dynasty. One of Kublai’s main advisers, Liu Bingzhong, submitted a memorial recommending the restoration of the examination system: however, this was not done.[45] Kublai ended the imperial examination system, as he believed that Confucian learning was not needed for government jobs.[46] Also, Kublai was opposed to such a commitment to the Chinese language and to the ethnic Han scholars who were so adept at it, as well as its accompanying ideology: he wished to appoint his own people without relying on an apparatus inherited from a newly conquered and sometimes rebellious country.[47] The discontinuation of the exams had the effect of reducing the prestige of traditional learning, reducing the motivation for doing so, as well as encouraging new literary directions not motivated by the old means of literary development and success.[48]

The examination system was revived in 1315, with significant changes, during the reign of Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan. The new examination system organized its examinees into regional categories in a way which favored Mongols and severely disadvantaged Southern Chinese. A quota system both for number of candidates and degrees awarded was instituted based on the classification of the four groups, those being the Mongols, their non-Han allies (Semu-ren), Northern Chinese, and Southern Chinese, with further restrictions by province favoring the northeast of the empire (Mongolia) and its vicinities.[49] A quota of 300 persons was fixed for provincial examinations with 75 persons from each group. The metropolitan exam had a quota of 100 persons with 25 persons from each group. Candidates were enrolled on two lists with the Mongols and Semu-ren located on the left and the Northern and Southern Chinese on the right. Examinations were written in Chinese and based on Confucian and Neo-Confucian texts but the Mongols and Semu-ren received easier questions to answer than the Han. Successful candidates were awarded one of three ranks. All graduates were eligible for official appointment.[21]

The Yuan decision to use Zhu Xi’s classical scholarship as the examination standard was critical in enhancing the integration of the examination system with Confucian educational experience. Both Chinese and non-Chinese candidates were recruited separately, to guarantee that non-Chinese officials could control the government, but this also furthered Confucianisation of the conquerors.[42]

— Thomas H. C. Lee

Under the revised system the yearly averages for examination degrees awarded was about 21.[49] The way in which the four regional racial categories were divided tended to favor the Mongols, Semu-ren, and North Chinese, despite the South Chinese being by far the largest portion of the population. The 1290 census figures record some 12,000,000 households (about 48% of the total Yuan population) for South China, versus 2,000,000 North Chinese households, and the populations of Mongols and Semu-ren were both less.[49] While South China was technically allotted 75 candidates for each provincial exam, only 28 Han Chinese from South China were included among the 300 candidates, the rest of the South China slots (47) being occupied by resident Mongols or Semu-ren, although 47 «racial South Chinese» who were not residents of South China were approved as candidates.[50]

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)[edit]

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) retained and expanded the system it inherited. The Hongwu Emperor was initially reluctant to restart the examinations, considering their curriculum to be lacking in practical knowledge. In 1370 he declared that the exams would follow the Neo-Confucian canon put forth by Zhu Xi in the Song dynasty: the Four Books, discourses, and political analysis. Then he abolished the examinations two years later because he preferred appointment by referral. In 1384, the examinations were revived again, however in addition to the Neo-Confucian canon, Hongwu added another portion to the exams to be taken by successful candidates five days after the first exam. These new exams emphasized shixue (practical learning), including subjects such as law, mathematics, calligraphy, horse riding, and archery. The emperor was particularly adamant about the inclusion of archery, and for a few days after issuing the edict, he personally commanded the Guozijian and county-level schools to practice it diligently.[51][52] As a result of the new focus on practical learning, from 1384 to 1756/57, all provincial and metropolitan examinations incorporated material on legal knowledge and the palace examinations included policy questions on current affairs.[53] The first palace examination of the Ming dynasty was held in 1385.[21]

Provincial and metropolitan exams were organized in three sessions. The first session consisted of three questions on the examinee’s interpretation of the Four Books, and four on the Classics corpus. The second session took place three days later, and consisted of a discursive essay, five critical judgments, and one in the style of an edict, an announcement and a memorial. Three days after that, the third session was held, consisting of five essays on the Classics, historiography, and contemporary affairs. The palace exam was just one session, consisting of questions on critical matters in the Classics or current affairs. Written answers were expected to follow a predefined structure called the eight-legged essay, which consisted of eight parts: opening, amplification, preliminary exposition, initial argument, central argument, latter argument, final argument, and conclusion. The length of the essay ranged between 550 and 700 characters. Gu Yanwu considered the eight-legged essay to be worse than the book burning of Qin Shi Huang and his burying alive of 460 Confucian scholars.[21]

The content of the examinations in the Ming and Qing times remained very much the same as that in the Song, except that literary composition was now widened to include government documents. The most important was the weight given to eight-legged essays. As a literary style, they are constructed on logical reasoning for coherent exposition. However, as the format evolved, they became excessively rigid, to ensure fair grading. Candidates often only memorised ready essays in the hope that the ones they memorised might be the examination questions. Since all questions were taken from the Classics, there were just so many possible passages that the examiners could use for questions. More often than not, the questions could be a combination of two or more totally unrelated passages. Candidates could be at a complete loss as to how to make out their meaning, let alone writing a logically coherent essay. This aroused strong criticism, but the use of the style remained until the end of the examination system.[42]

— Thomas H. C. Lee

The Hanlin Academy played a central role in the careers of examination graduates during the Ming dynasty. Graduates of the metropolitan exam with honors were directly appointed senior compilers in the Hanlin Academy. Regular metropolitan exam graduates were appointed junior compilers or examining editors. In 1458, appointment in the Hanlin Academy and the Grand Secretariat was restricted to jinshi graduates. Posts such as minister or vice minister of rites or right vice minister of personnel were also restricted to jinshi graduates. The training jinshi graduates underwent in the Hanlin Academy allowed them insight into a wide range of central government agencies. Ninety percent of Grand Chancellors during the Ming dynasty were jinshi degree holders.[21]

The Neo-Confucian orthodoxy became the new guideline for literati learning, narrowing the way in which they could politically and socially interpret the Confucian canon. At the same time, commercialization of the economy and booming population growth resulted in an inflation of the number of degree candidates at the lower levels. The Ming bureaucracy did not increase degree quotas in proportion to the increased population. Near the end of the Ming dynasty, in 1600, there were roughly 500,000 shengyuan in a population of 150 million, that is, one per 300 people. This trend of booming population but artificial limitation of degrees awarded continued into the Qing dynasty, when during the mid-19th century, the ratio of shengyuan to population had shrunk to one per each thousand people. Access to government office became not only extremely difficult, but officials also became more orthodox in their thinking. The higher and more prestigious offices were still dominated by jinshi degree-holders, similar to the Song dynasty, but tended to come from elite families.[54]

The social background of metropolitan graduates also narrowed as time went on. In the early years of the Ming dynasty only 14 percent of metropolitan graduates came from families that had a history of providing officials, while in the last years of the Ming roughly 60 percent of metropolitan exam graduates came from established elite families.

«Viewing the Pass List», attributed to Qiu Ying (c. 1494–1552), Ming dynasty. Handscroll, ink and colors on silk, 34.4 × 638 cm

Qing dynasty (1636–1912)[edit]

The ambition of Hong Taiji, the first emperor of the Qing dynasty, was to use the examinations to foster a cadre of Manchu Bannermen who were both martial and literate to administer the government. He initiated the first exam for bannermen in 1638, offered in both Manchu and Chinese, even before his troops took Beijing in 1644. But the Manchu bannermen had no time or money to prepare for the exams, especially since they could gain advancement on the battlefield, and the dynasty went on to rely on both Manchu and Han Chinese officials chosen through the system inherited with minor adaptation from the Ming. [55] During the dynasty a total of 26,747 jinshi degrees were earned in 112 examinations held over the 261 years 1644–1905, an average of 238.8 jinshi degrees conferred per examination.[56]