History of the Sari

The sari is a strip of unstitched cloth, worn by females, it is draped over the body in various styles which is native to the Indian Subcontinent. It is a seamless rectangular piece of fabric measuring between four to nine meters decorated with varying pattern, colour, design, and richness. The etymology (origin) of the word sari is from the Sanskrit word sati, which means strip of cloth. This evolved into the Prakrit sadi and was later anglicised into sari. There are more than 80 recorded ways to wear a sari.

In the history of Indian clothing the sari is traced back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, which flourished during 2800–1800 BC around the western part of the Indian subcontinent. The earliest known depiction of the sari in the Indian subcontinent is the statue of an IndusValley priest wearing a drape, or dhoti. This draping style was worn both by men and women.

Ancient Tamil poetry, such as the Silappadhikaram and the Sanskrit work, Kadambari by Banabhatta, describes women in exquisite drapery or sari. The ancient stone inscription from Gangaikonda Cholapuram in old Tamil scripts has a reference to hand weaving. In ancient Indian tradition and the Natya Shastra (an ancient Indian treatise describing ancient dance and costumes), the navel of the Supreme Being is considered to be the source of life and creativity, hence the midriff is to be left bare by the sari.

Sculptures from the Gandhara, Mathura and Gupta schools (1st–6th century AD) show goddesses and dancers wearing what appears to be a dhoti wrap, in the “fishtail” version which covers the legs loosely and then flows into a long, decorative drape in front of the legs. No bodices are shown.

The tightly fitted, short blouse worn under a sari is a choli. Choli evolved as a form of clothing in the 10th century AD, and the first cholis were only front covering; the back was always bare but covered with end of saris pallu. Bodices of this type are still common in the state of Rajasthan.

In South India and especially in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, it is indeed documented that women from many communities wore only the sari and exposed the upper part of the body till the early days of the 20th century. In Kerala there are many references to women being bare-breasted, which shocked the Europeans arriving on Indian shores.

Vintage Photographs of Indian Women show the various sari draping

image courtesy http://vintageindianpics.in/

Life Magazine did a series on Sari draping in 1951

image courtesy http://alkeemi.blogspot.nl/2011/06/how-to-wrap-sari.html

This unstitched cloth is commonly worn tucked at waist into and over a petticoat (antariya of historic Indian costumes), pleated and wrapped around the legs to make a long skirt and then thrown over the shoulder covering the upper body wearing a blouse (uttariya). This style of draping sari is called nivi, originally worn in Andhra Pradesh, India. Besides nivi various other draping styles also exists in India resulting from the regional influences namely Bengali, Gujarati, Maharashtrian, Dravidian, Gond, etc.

Usage of diverse colour, motif, pattern and weave over the untailored length of a sari make it a representation of rich regional traditions. The Sari is usually divided into three parts:

- An end-piece or pallu/pallav

- A field or jamin

- Border or kinara

The end-piece is the loose end of the sari covering the bosom and thrown over the shoulder. It is usually the most exposed and hence usually the most embellished part of the sari. The field of a sari may be embellished with prints, embroidery, etc or left plain as per design may be. The borders of a sari run along the entire length giving it an extraordinary appeal.

Decoration of the sari with distinct weave, motif and fabric as a result of regional influences has given us a wide variety to show interest in.

Contemporary styles of wearing a sari

The Nivi style is the most common style of wearing a sari today, though for festivals and marriages the traditional styles such as gujrati, navari,south indian half sari, bengali are still used.

Other Posts in this series:

Indian Textiles: Cotton Sari

Indian Textiles: History

The sari (or saree) is traditional attire for women of South Asian (especially Indian) descent and is essentially a long piece of fabric that is draped around the body. It is usually worn together with a short fitted blouse, known as a choli, and a long petticoat.1

Description

The sari is a length of unstitched cloth ranging from 3 to 8 m in length that is wrapped around a woman’s body.2 It covers both the upper and lower torso, and sometimes the head as well.3 There are three main parts to the sari: a field, borders and an end piece known as the pallu.4 The field is the main section that is draped around the wearer. Draping is done in a way to highlight the design and ornamentation of the field. The border runs the length of the sari along the edges and is meant to beautify the garment as well as to add weight at the edges to enable the fabric to fall nicely in place.5 The pallu is the end piece of the sari that is usually embellished and draped over the shoulder.6

There are many ways in which a sari can be draped. In the past, the way a sari was draped reflected its geographical origins. For example, in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, the sari was draped with back pleats to create a fan effect. Today, most Indian women adopt the popular nivi style where one end of the sari is tucked at the waist into the petticoat. It is then pleated and wound around the legs to form a long skirt that reaches the ankles. The remaining end is thrown over the shoulder or head.7

Saris come in a variety of colours, patterns and materials. They can be made from natural materials such as silk and cotton, or synthetic fabrics such as nylon and polyester. While traditionally woven on hand looms, most saris are now produced in factories using power looms.8

Historical development

The people of the Indian subcontinent have worn some form of draped clothing for centuries. It is believed that the forerunner of the sari emerged in the late 18th century in the form of an outfit that consisted of a skirt, a bodice and a sheer veil that fluttered around the body. This outfit gradually evolved into the sari.9

There were few Indian women in Singapore in the 19th and early 20th centuries as most Indian migrants who arrived during this period were single men who came as labourers or businessmen.10 The number of female Indian migrants to Singapore increased dramatically after World War II. Many of them migrated to Singapore in order to join their husbands or families. With this influx of Indian female migrants came their native dress, the sari.11

Over the years, the basic design of the sari has remained generally unchanged but the materials used to make them have. In the past, most saris were made of natural fibres such as silk and cotton, but synthetic materials such as polyester are most popular nowadays. The choli blouse that is worn with the sari has undergone various changes over the years. In the early 20th century, the choli had high necklines and long sleeves. Subsequently, the blouse and sleeves became shorter and the neckline lower.12

Modern varieties

Ready-made saris have become popular in recent years as they are easier to wear than traditional saris, which require skill and practice in draping. These modern saris come with zips, sewn-in pleats and elastic waistbands, making them convenient and comfortable to wear. They also come in a wide range of materials and colours to suit different budgets.13

Other modern uses

In addition to being worn as an outfit, the sari material is now also used for other products. For example, the decorative borders and pallus are used to make curtain panels, cushion covers, bags and other home textile products.14

Cultural significance

Traditionally, the wearing of the sari was regarded as a sign of maturity. In the past, the first time an Indian girl wore a sari was when she was presented as a potential bride during marriage discussions.15 Indian mothers would often start collecting saris for their daughters from a young age as part of her dowry. A traditional Indian wedding comprises a series of rituals in which the bride is expected to wear a different sari for each one.16

Cultural norms also influenced a woman’s choice of sari. Older women, for example, are expected to wear saris in dark tones while younger women are encouraged to wear bright colours. Red is a popular choice for wedding saris as it is regarded to be an auspicious colour.17

Author

Stephanie Ho

References

1. Costumes through time: Singapore. (1993). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Fashion Designers’ Society, p. 113. (Call no.: RSING q391.0095957 COS-[CUS])

2. Askari, N., & Arthur, L. (1999). Uncut cloth. London: Merrell Holberton, p. 23. (Call no.: RART q746.0954 ASK)

3. Anawalt, P. R. (2007). The worldwide history of dress. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 228. (Call no.: R 391.009 ANA-[CUS])

4. Askari, N., & Arthur, L. (1999). Uncut cloth. London: Merrell Holberton, p. 23. (Call no.: RART q746.0954 ASK)

5. Katiyar, V. S. (2009). Indian saris: traditions, perspectives, design. New Delhi: Wisdom Tree, p. 33. (Call no.: R 391.20954 KAT-[CUS])

6. Katiyar, V. S. (2009). Indian saris: traditions, perspectives, design. New Delhi: Wisdom Tree, p. 34. (Call no.: R 391.20954 KAT-[CUS])

7. Anawalt, P. R. (2007). The worldwide history of dress. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 228. (Call no.: R 391.009 ANA-[CUS]); Askari, N., & Arthur, L. (1999). Uncut cloth. London: Merrell Holberton, p. 23. (Call no.: RART q746.0954 ASK)

8. Banerjee. M., & Miller, D. (2005). Sari. In V. Steele (Ed.), Encyclopedia of clothing and fashion. Detroit: Thomson Gale, pp. 139–140. (Call no.: LR q391.003 ENC-[CUS])

9. Biswas, A. (1985). Indian costumes. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India, pp. 27–28. (Call no.: R 391.00954 BIS-[CUS])

10. Ang, M. W. (2000). Costumes of Singapore. In K. M. Chavalit & M. Phromsuthirak (Eds.), Costumes in ASEAN. Bangkok: The National ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information of Thailand, p. 208. (Call no.: RSING 391.00959 COS-[CUS])

11. Ang, M. W. (2000). Costumes of Singapore. In K. M. Chavalit & M. Phromsuthirak (Eds.), Costumes in ASEAN. Bangkok: The National ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information of Thailand, p. 213. (Call no.: RSING 391.00959 COS-[CUS])

12. Costumes through time: Singapore. (1993). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Fashion Designers’ Society, p. 113. (Call no.: RSING q391.0095957 COS-[CUS])

13. Chatterjee, J. (1993, November 11). Ready-made saris popular this Deepavali. The Straits Times, pp. 12–13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

14. Katiyar, V. S. (2009). Indian saris: traditions, perspectives, design. New Delhi: Wisdom Tree, p. 199. (Call no.: R 391.20954 KAT-[CUS])

15. Banerjee, M., & Miller, D. (2003). The sari. Oxford, New York: Berg, p. 65. (Call no.: R 391.20954 BAN-[CUS])

16. Banerjee. M. & Miller, D. (2005). Sari. In V. Steele (Ed.), Encyclopedia of clothing and fashion. Detroit: Thomson Gale, p. 140. (Call no.: LR q391.003 ENC-[CUS])

17. Askari, N., & Arthur, L. (1999). Uncut cloth. London: Merrell Holberton, p. 23. (Call no.: RART q746.0954 ASK)

The information in this article is valid as at 6 September 2013 and correct as far as we are able to ascertain from our sources. It is not intended to be an exhaustive or complete history of the subject. Please contact the Library for further reading materials on the topic.

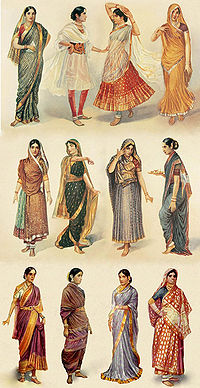

This painting by Raja Ravi Varma depicts several traditional styles of draping the sari

A sari or saree is the traditional female garment in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. A sari is a very long strip of unstitched cloth, ranging from four to nine meters in length, which can be draped in various styles. The most common style is for the sari to be wrapped around the waist, with one end then draped over the shoulder baring the midriff. The history of Indian clothing traces the sari back to the Indus valley civilization, which flourished from 2800-1800 B.C.E. It is generally accepted that wrapped sari-like garments, shawls, and veils have been worn by Indian women in their current form for hundreds of years.

Saris are woven with one plain end (the end that is concealed inside the wrap), two long decorative borders running the length of the sari, and a one- to three- foot section at the other end which continues and elaborates the length-wise decoration. This end is called the pallu; it is the part thrown over the shoulder in the Nivi style of draping. In past times, all saris were hand woven of silk or cotton, and represented a considerable investment of time or money. Sometimes warp and weft threads were tie-dyed and then woven, creating ikat patterns, or threads of different colors were woven into the base fabric in patterns; an ornamented border, an elaborate pallu, and often, small repeated accents were woven in the cloth itself. For fancy saris, these patterns could be woven with gold or silver thread (zari work). Sometimes the saris were further decorated, after weaving, with various sorts of embroidery, pearls and precious stones. Modern saris are increasingly woven on mechanical looms and made of artificial fibers, but hand-woven saris are still popular for weddings and other grand social occasions.

Sari

A sari or saree is the traditional female garment in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.[1][2] A sari is a very long strip of unstitched cloth, ranging from four to nine meters in length, which can be draped in various styles. The most common style is for the sari to be wrapped around the waist, with one end then draped over the shoulder baring the midriff.[1] The sari is usually worn over a petticoat (pavada/pavadai in the south, and shaya in eastern India), with a blouse known as a choli or ravika forming the upper garment. The choli has short sleeves and a low neck and is usually cropped, and as such is particularly well-suited for wear in the sultry South Asian summers. Cholis may be «backless» or of a halter neck style. These styles are usually more dressy, with a lot of embellishments such as mirrors or embroidery, and may be worn on special occasions. Women in the armed forces, when wearing a sari uniform, don a half-sleeve shirt tucked in at the waist.

Origins and History

Did you know?

The term «sari» is derived from a Sanskrit word meaning «strip of cloth»

Illustration of a sari-clad, barefoot woman, c. 1847

The word ‘sari’ evolved from the Prakrit sattika, as mentioned in earliest Buddhist and Jain literature.[3]

The history of Indian clothing traces the sari back to the Indus valley civilization, which flourished from 2800-1800 B.C.E.[1][2] The earliest known depiction of the sari in the Indian subcontinent is the statue of an Indus valley priest wearing a drape.[1][4]

Ancient Tamil poetry, such as the Silappadhikaram and the Kadambari by Banabhatta, describes women in exquisite drapery or saree.[5] In ancient Indian tradition and the Natya Shastra (an ancient Indian treatise describing ancient dance and costumes), the navel of the Supreme Being is considered to be the source of life and creativity, hence the midriff is to be left bare by the saree.[6][7]

Some costume historians believe that the men’s dhoti, which is the oldest Indian draped garment, is the forerunner of the sari. They say that until the fourteenth century, the dhoti was worn by both men and women.[2][1]

Sculptures from the Gandhara, Mathura and Gupta schools, from the first through the sixth centuries C.E., show goddesses and dancers wearing what appears to be a dhoti wrap, in the «fishtail» version which covers the legs loosely and then flows into a long, decorative drape in front of the legs. No bodices are shown.[1]

Other sources say that everyday costume consisted of a dhoti or lungi (sarong), combined with a breast band and a veil or wrap that could be used to cover the upper body or head. The two-piece Kerala mundum neryathum (mundu, a dhoti or sarong, neryath, a shawl, in Malayalam) is a survival of ancient Indian clothing styles; the one-piece sari is a modern innovation, created by combining the two pieces of the mundum neryathum.[8][4]

It is generally accepted that wrapped sari-like garments, shawls, and veils have been worn by Indian women for a long time, and that they have been worn in their current form for hundreds of years.

The history of the choli, or sari blouse, and the petticoat is a subject of controversy. Some researchers state that these were unknown before the British arrived in India, and that they were introduced to satisfy Victorian ideas of modesty. Previously, women only wore one draped cloth and casually exposed the upper body and breasts. Other historians point to much textual and artistic evidence for various forms of breastband and upper-body shawl which were worn much earlier.

In South India, it is indeed documented that women from many communities wore only the sari and exposed the upper part of the body until the twentieth century.[2] Poetic references from works like Shilappadikaram indicate that during the sangam period in ancient South India, a single piece of clothing served as both lower garment and head covering, leaving the bosom and midriff completely uncovered.[5] In Kerala there are many references to women being bare-breasted.[2][4] including many pictures by Raja Ravi Varma (1848 – 1906). Even today, women in some rural areas do not wear cholis. In the privacy of their homes, even city women sometimes find it convenient and comfortable to drape the sari as a cover-all, without the choli.

Styles of Draping

Illustration of different styles of sari & clothing worn by women in South Asia

The most common style of draping a sari is wrapped around the waist and the bust, with one end draped over the shoulder. However, the sari can be draped in several different styles. Some styles require a sari of a particular length or form.

Some of the styles are:

- North India: Also described below as the «Modern Style,» it is the most common way of wearing a sari (shown in the images below). The sari makes one circle around the waist, pleats, and makes one more half circle, with the loose end or «pallu» going over the left shoulder. The North Indian Style refers to the drape common to Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, Uttrakhand States.

Variations of the North Indian Style:

-

-

- In the north, the Pallu may also be draped again over the right shoulder, or over the head and over the right shoulder. This is usually done as a sign of respect for elders. The drape over the head is thought to be a Muslim influence from the intermingling cultures which was more pervasive in the North due to invasions.

- Over the shoulder and under the right arm (as shown in the picture with the yellow sari below)

-

- Nivi (sari drape) – styles originally worn in Tamil Nadu; besides the modern nivi, there is also the kaccha nivi, where the pleats are passed through the legs and tucked into the waist at the back. This allows free movement while covering the legs.

- Gujarati – this style differs from the nivi only in the manner in which the loose end is handled: in this style, the loose end is draped over the right shoulder rather than the left, and is also draped back-to-front rather than the other way around.

- Maharashtrian/Kache – This drape (front and back) is very similar to that of the male Maharashtrian dhoti. The center of the sari (held lengthwise) is placed at the center back, the ends are brought forward and tied securely, then the two ends are wrapped around the legs. When worn as a sari, an extra-long cloth is used and the ends are then passed up over the shoulders and the upper body. This style is primarily worn by Brahmin women of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

- Dravidian – sari drapes worn in Tamil Nadu; some (especially among the Singhalese in Sri Lanka) feature a pinkosu, or pleated rosette, at the waist.

A Tamil couple circa 1945; the wife is wearing a madisaara sari

- Madisaara style – This drape is typical of Brahmin ladies from Tamil Nadu and Kerala

- Kodagu style – This drape is confined to ladies hailing from the Kodagu district of Karnataka. In this style, the pleats are created in the rear, instead of the front. The loose end of the sari is draped back-to-front over the right shoulder, and is pinned to the rest of the sari.

- Gond – sari styles found in many parts of Central India. The cloth is first draped over the left shoulder, then arranged to cover the body.

- the two-piece sari, or mundum neryathum, worn in Kerala. A two-piece sari is usually made of unbleached cotton and decorated with gold or colored stripes and/or borders.

- tribal styles – often secured by tying them firmly across the chest, covering the breasts.

Part of the list above is quoted from Chantal Boulanger, French cultural anthropologist, who categorizes sari drapes into a few families.[4]

The nivi drape starts with one end of the sari tucked into the waistband of the petticoat. The cloth is wrapped around the lower body once, then hand-gathered into even pleats just below the navel. The pleats are also tucked into the waistband of the petticoat.[9] They create a graceful, decorative effect which poets have likened to the petals of a flower.

After one more turn around the waist, the loose end is draped over the shoulder.[9] The loose end is called the pallu or pallav. It is draped diagonally in front of the torso. It is worn across the right hip to over the left shoulder, partly baring the midriff.[9] The navel can be revealed or concealed by the wearer by adjusting the pallu, depending on the social setting in which the sari is being worn. The long end of the pallu hanging from the back of the shoulder is often intricately decorated. Some nivi styles are worn with the pallu draped from the back towards the front.

The Nivi saree was popularized through the paintings of Raja Ravi Verma.[8] by modifying the South Indian saree called mundum neriyathum. In one of his paintings, the Indian subcontinent was shown as a mother wearing a flowing nivi saree.[8]

In Pakistan

In Pakistan, the wearing of saris has almost completely been replaced by the shalwar kameez for everyday wear, though it remains a popular dress for formal functions, especially weddings among the Pakistani elite, and is currently gaining interest.[10] The sari is sometimes worn as daily-wear, mostly in Karachi, by those elderly women who were used to wearing it in pre-partition India.[11] The sari lost popularity in Pakistan, because it was viewed as a Hindu dress. Although she was seen wearing them,[11] Fatima Jinnah, the «Mother of the Nation,» called the sari «unpatriotic» and the wife of Pervez Musharraf’s wife has stated that she never wears them.[12]

In Sri Lanka

Sri Lankan women wear saris in many styles. However, two ways of draping the sari are popular and tend to dominate; the Indian style (classic nivi drape) and the Kandyan style (or osaria in Sinhalese). The Kandyan style is generally more popular in the hill country region of Kandy from which the style gets its name. Though local preferences play a role, most women decide on style depending on personal preference or what is perceived to be most flattering for their figure.

The traditional Kandyan (Osaria) style consists of a full blouse which covers the midriff completely, and is partially tucked in at the front as is seen in this nineteenth century portrait. However, modern intermingling of styles has led to most wearers baring the midriff. The final tail of the sari is neatly pleated rather than free-flowing. This is rather similar to the pleated rosette used in the ‘Dravidian’ style noted earlier in the article.

The Sari as Cloth

Saris being laundered and left to dry

Group of sari-clad women wearing everyday saris in Ujjain

Saris are woven with one plain end (the end that is concealed inside the wrap), two long decorative borders running the length of the sari, and a one- to three- foot section at the other end which continues and elaborates the length-wise decoration. This end is called the pallu; it is the part thrown over the shoulder in the Nivi style of draping.

In past times, saris were woven of silk or cotton. The rich could afford finely-woven, diaphanous silk saris that, according to folklore, could be passed through a finger-ring. The poor wore coarsely woven cotton saris. All saris were handwoven and represented a considerable investment of time or money.

Simple hand-woven villagers’ saris are often decorated with checks or stripes woven into the cloth. Inexpensive saris were also decorated with block printing using carved wooden blocks and vegetable dyes, or tie-dyeing, known in India as bhandani work.

More expensive saris had elaborate geometric, floral, or figurative ornament created on the loom, as part of the fabric. Sometimes warp and weft threads were tie-dyed and then woven, creating ikat patterns. Sometimes threads of different colors were woven into the base fabric in patterns; an ornamented border, an elaborate pallu, and often, small repeated accents were woven in the cloth itself. These accents are called buttis or bhutties (spellings vary). For fancy saris, these patterns could be woven with gold or silver thread, which is called zari work.

Sometimes the saris were further decorated, after weaving, with various sorts of embroidery. Resham work is embroidery done with colored silk thread. Zardozi embroidery uses gold and silver thread and sometimes pearls and precious stones. Cheap modern versions of zardozi use synthetic metallic thread and imitation stones, such as faux pearls and Swarovski crystals.

In modern times, saris are increasingly woven on mechanical looms and made of artificial fibers, such as polyester, nylon, or rayon, which do not require starching or ironing. They are printed by machine, or woven in simple patterns made with floats across the back of the sari. This can create an elaborate appearance on the front, while looking ugly on the back. The punchra work is imitated with inexpensive machine-made tassle trim.

Hand-woven, hand-decorated saris are naturally much more expensive than the machine imitations. While the over-all market for hand-weaving has plummeted (leading to much distress among Indian hand-weavers), hand-woven saris are still popular for weddings and other grand social occasions.

Types of Saris

- Kantha– West Bengal

While an international image of the ‘modern style’ sari may have been popularized by airline stewardesses, each region in the Indian subcontinent has developed, over the centuries, its own unique sari style. Following are the well known varieties, distinguished by type of fabric, weaving style, or motif, in South Asia:

Northern styles

- Chikan – Lucknow

- Banarasi – Benares

- Tant

- Jamdani

- Tanchoi

- Shalu

Eastern Styles

- Baluchari West Bengal

- Ikat – Orissa

- Jamdani – Bangladesh

- Dhakai Benarosi– Bangladesh

- Rajshahi Silk– Bangladesh

- Tangail Tanter Sari– Bangladesh

- Katan Sari– Bangladesh

Western Styles

- Paithani – Maharashtra

- Bandhani – Gujarat and Rajasthan

- Kota doria Rajasthan

- Lugade – Maharashtra

Central Styles

- Chanderi – Madhya Pradesh

Southern Styles

- Pochampally Andhra Pradesh

- Venkatagiri – Andhra Pradesh

- Gadwal – Andhra Pradesh

- Guntur – Andhra Pradesh

- Narayanpet – Andhra Pradesh

- Mangalagiri – Andhra Pradesh

- Balarampuram – Kerala

- Coimbatore – Tamil Nadu

- Kanchipuram (locally called Kanjivaram) – Tamil Nadu

- Chettinad – Tamil Nadu

- Mysore Silk – Karnataka

- Ilkal saree – Karnataka

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Roshen Alkazi, Ancient Indian Costume (South Asia Books, 1985, ISBN 978-0836413342).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 G.S. Ghurye, Indian Costume (Bombay: Popular book depot, 1951).

- ↑ R.P. Mohapatra, Fashion Styles of Ancient India (B.R. Publishing corporation, 1992, ISBN 8170187230).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Chantal Boulanger, Saris: An Illustrated Guide to the Indian Art of Draping. (New York: Shakti Press International, ISBN 0966149610).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 R. Parthasarathy, The Tale of an Anklet: An Epic of South India, – The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal, Translations from the Asian Classics (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1993, ISBN 0231078498).

- ↑ Bharata, The Natyashastra [Dramaturgy] (Calcutta: Manisha Granthalaya, 1967).

- ↑ Brenda Beck, «The Symbolic Merger of Body, Space, and Cosmos in Hindu Tamil Nadu.» Contributions to Indian Sociology 10(2) (1976): 213-243.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mukulika Banerjee and Daniel Miller, The Sari (Oxford, UK: Berg, 2003, ISBN 1859737323).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kamala S. Dongerkery, The Indian Sari (New Delhi: Government of India, 1961).

- ↑ Sudha Ramachandran, Bollywood, saris and a bombed train. Asia Times, February 23, 2007. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ramachandra Guha, The spread of the salwar. The Hindu, October 24, 2004. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ↑ Sunanda K. Datta-Ray, Meanwhile: Unraveling the sari. The New York Times, April 28, 2005. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alkazi, Roshen. Ancient Indian Costume. South Asia Books, 1985. ISBN 978-0836413342

- Ambrose, Kay. Classical Dances and Costumes of India. Palgrave Macmillan, 1984. ISBN 978-0312142636

- Banerjee, Mukulika, and Daniel Miller. The Sari. Oxford, UK: Berg, 2003. ISBN 1859737323

- Beck, Brenda. «The Symbolic Merger of Body, Space, and Cosmos in Hindu Tamil Nadu.» Contributions to Indian Sociology 10(2) (1976): 213-43.

- Bharata. The Natyashastra [Dramaturgy], 2 vols., 2nd. ed. Trans. by Manomohan Ghosh. Calcutta: Manisha Granthalaya, 1967.

- Boulanger, Chantal. Saris: An Illustrated Guide to the Indian Art of Draping. New York: Shakti Press International, 1997. ISBN 0966149610

- Dongerkery, Kamala, S. The Indian Sari. New Delhi: Government of India, 1961. ASIN B0007JGZY4

- Ghurye, G.S. Indian Costume. Bombay: Popular book depot, 1951. ASIN B004VJG1WC (Includes rare photographs of 19th century Namboothiri and nair women in ancient saree with bare upper torso).

- Mohapatra, R.P. Fashion Styles of Ancient India. B.R. Publishing corporation, 1992. ISBN 8170187230

- Parthasarathy, R. The Tale of an Anklet: An Epic of South India, – The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal, Translations from the Asian Classics. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1993. ISBN 0231078498

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- How to wear a sari.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Sari history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Sari»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Sari might be a fashionable garment now, but it started from being a humble drape used by women thousands of years ago. The origin of the drape or a garment similar to the sari can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, which came into being during 2800–1800 BC in north west India.

The beginning

The journey of sari began with cotton, which was first cultivated in the Indian subcontinent around 5th millennium BC. The cultivation was followed by weaving of cotton which became big during the era, as weavers started using prevalent dyes like indigo, lac, red madder and turmeric to produce the drape used by women to hide their modesty.

The name

The garment evolved from a popular word ‘sattika’ which means women’s attire, finds its mention in early Jain and Buddhist scripts. Sattika was a three-piece ensemble comprising the Antriya — the lower garment, the Uttariya — a veil worn over the shoulder or the head and the Stanapatta which is a chest band. This ensemble can be traced to Sanskrit literature and Buddhist Pali literature during the 6th century BC. The three piece set was known as Poshak, the Hindi term for costume.

Antriya resembled the dhoti or the fishtail style of tying a sari. It further evolved into Bhairnivasani skirt, which went onto be known as ghagra or lehenga. Uttariya evolved into dupatta and Stanapatta evolved into the choli.

Women traditionally wore various types of regional handloom saris made of silk, cotton, ikkat, block-print, embroidery and tie-dye textiles. Most sought after brocade silk sarees are Banarasi, Kanchipuram, Gadwal, Paithani, Mysore, Uppada, Bagalpuri, Balchuri, Maheshwari, Chanderi, Mekhela, Ghicha, Narayan pet and Eri etc.

Evolution

Years later with the advent of foreigners, the rich Indian women started asking the artisans to use expensive stones, gold threads to make exclusive saris for the strata, which could make them stand out, clearly. But sari did remain unbiased as a garment and was adapted by each strata, in their own way. That was the beauty of the garment, that still remains.

With industrialisation entering India, with the Britishers, synthetic dyes made their official entry. Local traders started importing chemical dyes from other countries and along came the unknown techniques of dyeing and printing, which gave Indian saris a new unimaginable variety.

The development of textiles in India started reflecting in the designs of the saris — they started including figures, motifs, flowers. With increasing foreign influence, sari became the first Indian international garment.

What started as India’s first seamless garment, went onto become the symbol of Indian femininity.

Photos: Wikipedia Commons

History of clothing in the Indian subcontinent can be traced to the Indus Valley civilization or earlier. Indians have mainly worn clothing made up of locally grown cotton. India was one of the first places where cotton was cultivated and used even as early as 2500 BCE during the Harappan era. The remnants of the ancient Indian clothing can be found in the figurines discovered from the sites near the Indus Valley civilisation, the rock-cut sculptures, the cave paintings, and human art forms found in temples and monuments. These scriptures view the figures of human wearing clothes which can be wrapped around the body. Taking the instances of the sari to that of turban and the dhoti, the traditional Indian wears were mostly tied around the body in various ways.

Indus Valley Civilisation periodEdit

Evidence for textiles in Indus Valley civilisation are not available from preserved textiles but from impressions made into clay and from preserved pseudomorphs. The only evidence found for clothing is from iconography and some unearthed Harappan figurines which are usually unclothed.[1] These little depictions show that usually men wore a long cloth wrapped over their waist and fastened it at the back (just like a close clinging dhoti). Turban was also in custom in some communities as shown by some of the male figurines. Evidence also shows that there was a tradition of wearing a long robe over the left shoulder in higher class society to show their opulence. The normal attire of the women at that time was a very scanty skirt up to knee length leaving the waist bare. Cotton made headdresses were also worn by the women.[2] Women also wore long skirt, stitched tight tunic on their upper body and trousers as well. Inferences from mother goddess statue from Delhi National Museum suggests female wearing a short tunic with a short skirt and trousers.[3] There also evidences of men wearing trousers, conical gown/tunic with an upper waist band.[4] The mother goddess statues show women also wearing heavy earrings which were also pretty common in the historic period of India and also depict with heavy necklaces with overhanging medallion with holes in them for gemstones. Female statues and terracotta arts and figurines like a dancing girl also depict long hairs probably braided and draped in cloth.

Fibre for clothing generally used were cotton, flax, silk, wool, linen, leather, etc. One fragment of colored cloth is available in pieces of evidence which are dyed with red madder show that people in Harappan civilisation dyed their cotton clothes with a range of colors.

One thing was common in both the sexes that both men and women were fond of jewelry. The ornaments include necklaces, bracelets, earrings, anklet, rings, bangles, pectorals, etc. which were generally made of gold, silver, copper, stones like lapis lazuli, turquoise, amazonite, quartz, etc. Many of the male figurines also reveal the fact that men at that time were interested in dressing their hair in various styles like the hair woven into a booty, hair coiled in a ring on the top of the head, beards were usually trimmed. Indus Valley Civilization men are frequently depicted wearing headbands especially to contain hair bun at the back. People have been shown wearing elaborate headdresses like turban, conical hats, pakol hats.[4]

Dressing of Indus valley civilization people show presence of multi-ethnic people of diverse backgrounds for instance people have been depicted wearing Pashtun style pakol hat with a chocker like neck ornament as well as Punjabi style pagri and Rajasthani style bangles and necklaces and many other styles prominent in neighbouring regions of the Indian subcontinent.

Some scholars, such as Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, have argued that headdress from the royal cemetery of Ur is an import from Indus Valley Civilization since similar headdresses have been found to have been depicted in many of its Mother Goddess figurines and actual ones discovered from sites such as Kunal and the floral depiction in gold leaves of species native to Indian subcontinent such as Dalbergia sissoo or pipal, and since no such ornamentation has been shown in Mesopotamian art itself.[5]

-

Woman’s statue from the Indus Valley Civilization wearing heavy earrings.

-

Woman’s statue wearing tight-fitted short tunic with skirt part fastened with a broad waistband using a medallion like clasp, and tight-fitted trousers, necklaces, ear-ornaments.

-

Woman’s statue wearing ornate necklace.

-

Royal cemetery of Ur headdress according to some scholars is a direct import from Indus valley civilization and similar headdress has been discovered at site of Kunal

-

Indus Civiliation carnelian bead necklace

-

Dancing girl statue from Mohenjo-daro, with one arm completely filled with bangles.

Ancient periodEdit

Vedic periodEdit

The Vedic period was the time duration between 1500 and 500 BCE. The garments worn in the Vedic period mainly included a single cloth wrapped around the whole body and draped over the shoulder. People used to wear the lower garment called paridhana which was pleated in front and used to tie with a belt called mekhala and an upper garment called uttariya (covered like a shawl) which they used to remove during summers. «Orthodox males and females usually wore the uttariya by throwing it over the left shoulder only, in the style called upavita«.[6] There was another garment called pravara that they used to wear in cold. This was the general garb of both the sexes but the difference existed only in size of cloth and manner of wearing. Sometimes the poor people used to wear the lower garment as a loincloth only while the wealthy would wear it extending to the feet as a sign of prestige.

In the Rig Veda, mainly three terms were described like Adhivastra, Kurlra, and Andpratidhi for garments which correspondingly denotes the outer cover (veil), a head-ornament or head-dress (turban) and part of woman’s dress. Many pieces of evidence are found for ornaments like Niska, Rukma were used to wear in the ear and neck; there was a great use of gold beads in necklaces which show that gold was mainly used in jewellery. Rajata-Hiranya (white gold), also known as silver was not in that much of use as no evidence of silver is figured out in the Rig Veda.

In the Atharva Veda, garments began to be made of the inner cover, an outer cover, and a chest-cover. Besides Kurlra and Andpratidhi (which already mentioned in the Rig Veda), there are other parts like as Nivi, Vavri, Upavasana, Kumba, Usnlsa, and Tirlta also appeared in Atharva Veda, which correspondingly denotes underwear, upper garment, veil and the last three denoting some kinds of head-dress (head-ornament). There were also mentioned Updnaha (Footwear) and Kambala (blanket), Mani (jewel) is also mentioned for making ornaments in this Vedic text.

Pre-Mauryan eraEdit

Even though scholars have debated the archaeological evidence from the pre-Mauryan era, a lot of terracotta artifacts by various scholars have been dated to the pre-Mauryan era which shows continuity of the dressing styles leading up to the Mauryan period.[7] The terracotta also contain naturalistic style of depicting human faces just like Mauryan periods. The pre-Mauryan periods have been marked by the continuation of Indus arts and depict elaborate headdresses, conical hats with heavy earring. Bronze rattling mirror excavated from Pazyryk dated to the 4th century BC also depict Indians wearing typical Indian classical clothing such as dhoti wrap and tight-fitting half sleeved stitched shirts like kurta.[8] Another pre-Mauryan archaeological evidence of Indian dressing comes from Saurashtra janapada coins which are one of the earliest representations of Indian pre-Mauryan arts. The coins are dated between 450 and 300 BCE and have been repeatedly over struck just like punch-marked coins.[9]

-

Statue of Magadhan king Udayin wearing drapes.

Mauryan periodEdit

During the Mauryan dynasty (322–185 BC) the earliest evidence of stitched female clothing is available from the statue of a woman(from Mathura, 3rd century BCE). Ladies in the Mauryan Empire often used to wear an embroidered fabric waistband with drum-headed knots at the ends. As an upper garment, people’s main garment was uttariya, a long scarf. The difference existed only in the manner of wearing. Sometimes, its one end is thrown over one shoulder and sometimes it is draped over both shoulders.

In textiles, mainly cotton, silk, linen, wool, muslin, etc. are used as fibers. Ornaments latched on to a special place in this era also. Some of the jewelry had their specific names also. Satlari, chaulari, paklari were some of the necklaces.

Men wore Antariya (knee-length, worn in kachcha style with the fluted end tucked in at center front) and Tunic (one of the earliest depictions of the cut and sewn garment; it has short sleeves and a round neck, full front opening with ties at the neck and waist, and is hip length). A statue of a warrior shows Boots (fitting to the knees cap) and a band (tied at the back over short hair). A broad flat sword with cross straps on the sheath is suspended from the left shoulder.

-

Yakshini wearing dhoti wrap and elaborate necklace, Mauryan period.

-

Hair styles of the Mauryan period.

-

Mauryan head with a conical hat from Sarnath.

Classical periodEdit

Early classical periodEdit

Early classical period has ample evidence of dresses worn by ancient Indians in several relief sculptures which depict not only the dressing styles, but also architecture and lifestyle of the period. Buddhist reliefs from Amravathi, Gandhara, Mathura, and many other sites contain carved reliefs from Jataka tales and exhibit the fashion of the period between the 2nd century BCE to Gupta periods.

-

Shunga royal family wearing traditional Indian attire, West Bengal, 1st century BCE.

-

Scene of the life of the Buddha, wearing kāṣāya, 2nd–3rd-century CE.

Gupta periodEdit

The Gupta period lasted from 320 CE to 550 CE. Chandragupta I was the founder of this empire. Stitched garments became very popular in this period. Stitched garments became a sign of royalty.

The antariya worn by the women turned into gagri, which has many swirling effects exalted by its many folds. Hence dancers used to wear it a lot. As it is evident from many Ajanta paintings,[11] women used to wear only the lower garment in those times, leaving the bust part bare but these depictions may be a stylistic representation of mother goddess cult since Indus Valley Civilization. Whereas women with stitched upper body garment or tunic have been shown from pre-Mauryan period as early as 400 BCE in a folk art depicted on Pazyryk rattling mirrors.[12] Ujjain coin from 200 BCE depicts a man wearing achkan. Depictions from terracotta clay tablets from Chandraketugarh show women wearing clothes made of muslin. Various kinds of blouses (cholis) evolved. Some of them had strings attached leaving the back open while others were used to tie from the front side, exposing the midriff.

Clothing in the Gupta period was mainly cut and sewn garments. A long sleeved brocaded tunic became the main costume for privileged people like the nobles and courtiers. The main costume for the king was most often a blue closely woven silk antariya, perhaps with a block printed pattern. In order to tighten the antariya, a plain belt took the position of kayabandh.

Mukatavati (necklace which has a string with pearls), kayura (armband), kundala (earring), kinkini (small anklet with bells), mekhala (pendant hung at the centre, also known as katisutra), nupura (anklet made of beads) were some of the ornaments made of gold, used in that time. There was extensive use of ivory during that period for jewellery and ornaments.

During the Gupta period, men used to have long hair along with beautiful curls and this style was popularly known as gurna kuntala style. In order to decorate their hair, they sometimes put headgear, a band of fabric around their hairs. On the other hand, women used to decorate their hair with luxuriant ringlets or a jewelled band or a chaplet of flowers. They often used to make a bun on the top of the head or sometimes low on the neck, surrounded by flowers or ratnajali (bejewelled net) or muktajala (net of pearls).

-

Terracotta head, wearing possibly an early form of pagri from the Gupta period.

-

Male warrior holding broad sword wearing dhoti and arm bracelets; Gupta era statues.

In southEdit

Chalukyas of vatapiEdit

Chalukyas of vatapi have unique clothing, they wore veshti in different styles sometimes veshti goes under knees. The uniqueness of jewelleries is the presence of thigh band.

Jewelleries worn by people in early chalukyan era as showed in badami cave Temples

Jewelleries and clothing in early chalukyan era as sculptured in badami cave Temples

Female veshtis of badami chalukyas

Medieval periodEdit

From post-Gupta period, there is plentiful evidence of Indian clothing from paintings such as in Alchi monastery, Bagan temples, Pala miniature paintings, Jain miniature paintings, Ellora caves paintings and Indian sculptures. Ancient Indians wearing kurta and baggy pants like shalwar have been depicted in 8-10th century CE ivory sculpture of an elephant chess piece from Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France.[13] From the Late medieval period, there are increased evidences of pajamas and shalwar becoming common in Indian attire while unstitched dhoti keeps its prominence as well. From Al-Biruni’s Tarikh ul Hind. The kurtas, which are called Kurtakas in Sanskrit, are half sleeved shirts with slits of both sides are described along with other clothing such as Kurpasaka which is a type of jacket similar to kurta, he also mentions that some Indians preferred dhoti while others dressed more by wearing baggy trousers similar to shalwar.[14] The Alchi painting also shows evidence of modern sari draping and Bagan temple paintings frequently depict Indians with long beards wearing big earring. Paintings from regions of the Indian subcontinent, including Bihar, Bengal, Indus Valley and Nepal depict various clothing attires of eastern Indian states including modern styles of wearing dupatta.

-

A teacher and a pupil. 11-12th-century palm leaf painting in eastern India.

-

Painting of a Shyama Tara with a three-piece sari from Alchi Monastery.

-

Ladies wearing muslin dupatta in a 12-13th century CE Buddhist manuscript.

Early Modern periodEdit

Mughal EmpireEdit

The Mughal dynasty included luxury clothes that complemented interest in art and poetry. Both men and women were fond of jewellery. Clothing fibers generally included muslins of three types: Ab-e-Rawan (running water), Baft Hawa (woven air) and Shabnam (evening dew) and the other fibers were silks, velvets and brocades. Mughal royal dresses consisted of many parts as listed below. Mughal women wore a large variety of ornaments from head to toe.[15] Their costumes generally included Pajama, Churidar, Shalwar, Garara and the Farshi , they all included head ornaments, anklets, and necklaces. This was done as a distinctive mark of their prosperity and their rank in society.

During the Mughal period, there was an extensive

tradition of wearing embroidered footwear, With ornamented leather and decorated with the art of Aughi. Lucknow footwear was generally favoured by nobles and kings.

RajputsEdit

Rajputs emerged in the 7th and 8th century as a community of Ancient Kshatriya people. Rajputs followed a traditional lifestyle for living which shows their martial spirit, ethnicity, and chivalric grandeur.

MenEdit

Rajput’s main costumes were the aristocratic dresses (court-dress) which includes angarkhi, pagdi, chudidar pyjama and a cummerbund (belt). Angarkhi (short jacket) is long upper part of garments which they used to wear over a sleeveless close-fitting cloth. Nobles of Ahirs generally attired themselves in the Jama, Shervani as an upper garment and Salvar, Churidar-Pyjama (a pair of shaped trousers) as lower garments. The Dhoti was also in tradition in that time but styles were different to wear it. Tevata style of dhoti was prominent in the desert region and Tilangi style in the other regions. Ahir style dhoti were give royal look .

WomenEdit

«To capture the sensuality of the female figures in Rajput paintings, women were depicted wearing transparent fabrics draped around their bodies».[16] Rajput women’s main attire was the Sari (wrapped over whole body and one of the ends thrown on the right shoulder) or Lengha related with the Rajasthani traditional dress. On the occasion (marriage) women preferred Angia. After marriage of Kanchli, Kurti, and angia were the main garb of women. The young girls used to wear the Puthia as an upper garment made of pure cotton fabric and the Sulhanki as lower garments (loose pajama). Widows and unmarried women clothed themselves with Polka (half sleeved which ends at the waist) and Ghaghra as a voluminous gored skirt made of line satin, organza or silk. Another important part of clothing is Odhna of women which are worked in silk.

Jewellery preferred by women were exquisite in the style or design. One of the most jewellery called Rakhdi (head ornament), Machi-suliya (ears) and Tevata, Pattia, and the aad (all is necklace). Rakhdi, nath and chuda show the married woman’s status. The footwear is the same for men and women and named Juti made of leather.

SikhsEdit

Sikhism was founded in the 15th century. In 1699, the last guru of Sikhism, Guru Gobind Singh mandated Khalsa Sikh men to have uncut hair for their lives, which they wear into a turban or dastar. The dastar has since then been an integral part of the Sikh culture.

British colonial periodEdit

During the British colonial period, Indian clothing went through many changes and began to reflect an evident European influence. The British had a strict set of rules for attire, as they viewed themselves as culturally superior. These new clothing norms arrived alongside new rules around government, education, and class structure.[17]

Upper and middle-class Indian men wore western clothing in public, often doing so because it brought them closer to being equal with European men. At first, this included combining elements of Indian and Western clothing, as some men would wear a ‘dhoti’ (loose lower garment) with a shirt and coat. Others started wearing a sherwani, which fused together the British frock coat and an achkan. Eventually, some men started wearing full European styles, like a pantsuit. Although one major difference that remained between Indian and European men’s fashion was the style and etiquette of head coverings. Some Indian men wore this for religious purposes, like turbans and phetas. For Indian men, it was important to wear this at all times in public, whereas European men would generally remove it. Thus, we see that Indian men’s fashion experienced changes through the fusion of cultures.[18]

Women’s clothing and fashion were also influenced by the British. They did not wear fully western clothes like men, but many started to wear petticoats and certain blouse styles under their saris.[19] Both of these articles of clothing were brought to India by Europeans. These new articles of clothing also created some tension between castes. One major instance of this was in Kerala, where only upper-caste women were allowed to wear blouses. Though, from 1813 to 1859 the Channar Revolt was supported by Christian missionaries who wanted Indian women to wear blouses.[20]

Another influence of the British on Indian women’s clothing was the introduction of new materials. They started using mill-made cloth and other imported satins and artificial silks.[21] A few reasons for using these new materials include that they were cheaper to produce and were more versatile than the cloth used in India. Sometimes these new styles were also more functional for Indian women. The adoption of these new textiles and styles was seen as a sign of upward mobility in British-Indian society.[22]

The British also impacted the textile industry in India because of industrialization and using their own mills instead of artisans in India. This led to the unemployment of many Indians. Later, Gandhi called for Indian people to make and wear their own hand-spun clothing, called khadi cloth, as a sign of resistance against the British.[23] This was part of the Swadeshi movement. In fact, we can see that small-scale artisan clothing producers did not disappear from India during the 20th century as they continued to make up a significant share of industrial output.[24]

Shares of Textile Industrial Output Over the 20th Century in India[25]

Post-IndependenceEdit

Western clothing has gained increasing popularity, especially in the metropolitan cities. This has also led to the development of the Indo-Western style. Bollywood has also been a major influence in fashion around the subcontinent, especially in Indian fashion.

GalleryEdit

-

Picture shows saree draping style of North Karnataka by Raja Ravi Varma. Front side — shows nivi drape, front pleats tucked left to right manner in a pouch. Back side — kaccha

See alsoEdit

- Clothing in India

- Folk costume

- History of Textile industry in India

- Indo-Western clothing

- Fashion in India

- 1950s in Indian fashion

- 1960s in Indian fashion

- 1970s in Eastern fashion

- 1980s in Indian fashion

- 1990s in Indian fashion

- 2000s in Asian fashion

- 2010s in Indian fashion

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Keay, John, India, a History. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

- ^ kenoyer, j.m. (1991). «Ornament Styles of the Indus Valley Tradition : Evidence from Recent Excavations at Harappa, Pakistan». Paléorient. 17 (17–2): 79–98. doi:10.3406/paleo.1991.4553.

- ^ «Standing figure of the Mother Goddess C. 2700-2100 B.C.» Archived from the original on 2013-05-16.

- ^ a b «Lady of the spiked throne» (PDF). www.harappa.com. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ Vidale, Massimo (January 2011). «M. Vidale, PG 1237, Royal Cemetery of Ur: Patterns in Death». Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 21 (3): 427–51. doi:10.1017/S095977431100045X. S2CID 154507819.

- ^ Ayyar, Sulochana (1987). Costumes and Ornaments as Depicted in the Sculptures of Gwalior Museum. Mittal Publications. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9788170990024.

- ^ Gupta, C. C. Das (1951). «Unpublished Ancient Indian Terracottas Preserved in the Musée Guimet, Paris». Artibus Asiae. 14 (4): 283–305. doi:10.2307/3248779. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3248779.

- ^ Vassilkov, Yaroslav V. «Pre-Mauryan «Rattle-Mirrors» with Artistic Designs from Scythian Burial Mounds of the Altai Region in the Light of Sanskrit Sources» (PDF).

- ^ «The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Surashtra Janapada». coinindia.com. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- ^ Mitra, Rajendralala (1875). The Antiquities of Orissa. Wyman. pp. 178 Two views of the figure in queen’s palace cave of Udayagiri showing the boots and the style of the jama or long coat in use in ancient India.

- ^ Harle, J.C. (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent (2nd ed.). Yale University Press Pelican History of Art. ISBN 978-0300062175.

- ^ «Pre-Mauryan «Rattle-Mirrors» with Artistic Designs from Scythian Burial Mounds of the Altai Region in the Light of Sanskrit Sources» (PDF). www.laurasianacademy.com. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ Flood, Finbarr Barry (2015). A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 377–379. ISBN 978-1119019534.

- ^ Yadava, Ganga Prasad (1982). DHANAPALA aND HIS TIMES. Concept Publishing Company.

- ^ Dey, Sumita. «Fashion, Attire and Mughal women: A story behind the purdha» (PDF).

- ^ Abbasi, Sana Mahmoud. «A Comparison Study between Rajput & Mughal Indian Miniature Paintings» (PDF). 2 (2): 3.

- ^ «A Brief History of Dress, Difference and Fashion Change in India». Indian Fashion: 25–48. 2015. doi:10.5040/9781474232364.ch-002.

- ^ Gupta, Toolika. «The Influence of British Raj on Indian Fashion».

- ^ «A Brief History of Dress, Difference and Fashion Change in India». Indian Fashion: 25–48. 2015. doi:10.5040/9781474232364.ch-002.

- ^ K D, Binu; Manoharan, Manosh (2021-10-08). «Absence in Presence: Dalit Women’s Agency, Channar Lahala, and Kerala Renaissance». Journal of International Women’s Studies. 22 (10): 17–30. ISSN 1539-8706.

- ^ «COLONIAL PERIOD». INDIAN CULTURE. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ «A Brief History of Dress, Difference and Fashion Change in India». Indian Fashion: 25–48. 2015. doi:10.5040/9781474232364.ch-002.

- ^ Victoria and Albert Museum, Digital Media webmaster@vam ac uk (2015-09-29). «The Fabric of India: Textiles in a Changing World». www.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/book/7358/chapter/152152209. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/crawlprevention/governor?content=%2fbook%2f7358%2fchapter%2f152152209. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

Handloom silk saris on display 20th century, Honolulu Museum of Art.

A sari (sometimes also saree[1] or shari)[note 1] is a women’s garment from the Indian subcontinent,[2] that consists of an un-stitched stretch of woven fabric arranged over the body as a robe, with one end tied to the waist, while the other end rests over one shoulder as a stole (shawl),[3] sometimes baring a part of the midriff.[4][5][6] It may vary from 4.1 to 8.2 metres (4.5 to 9 yards) in length,[7] and 60 to 120 centimetres (24 to 47 inches) in breadth,[8] and is form of ethnic wear in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. There are various names and styles of sari manufacture and draping, the most common being the Nivi style.[9][10] The sari is worn with a fitted bodice commonly called a choli (ravike or kuppasa in southern India, and cholo in Nepal) and a petticoat called ghagra, parkar, or ul-pavadai.[11] It remains fashionable in the Indian Subcontinent today.[12]

Etymology[edit]

The Hindustani word sāṛī (साड़ी, ساڑی),[13] described in Sanskrit शाटी śāṭī[14] which means ‘strip of cloth’[15] and शाडी śāḍī or साडी sāḍī in Pali, and which evolved to sāṛī in modern Indian languages.[16] The word śāṭika is mentioned as describing women’s dharmic attire in Sanskrit literature and Buddhist literature called Jatakas.[17] This could be equivalent to the modern day sari.[17] The term for female bodice, the choli evolved from ancient stanapaṭṭa.[18][19] Rajatarangini, a tenth-century literary work by Kalhana, states that the choli from the Deccan was introduced under the royal order in Kashmir.[11]

The petticoat is called sāyā (साया, سایہ) in Hindi-Urdu,[13] parkar (परकर) in Marathi, ulpavadai (உள்பாவாடை) in Tamil (pavada in other parts of South India: Malayalam: പാവാട, romanized: pāvāṭa, Telugu: పావడ, romanized: pāvaḍa, Kannada: ಪಾವುಡೆ, romanized: pāvuḍe), sāẏā (সায়া) in Bengali and eastern India, and sāya (සාය) in Sinhalese. Apart from the standard «petticoat», it may also be called «inner skirt»[20] or an inskirt.

Origins and history[edit]

Terracotta figurine in Sari-like drape, 200-100 BCE from Bengal.

Tara depicted in ancient three-piece attire, c. 11th century CE.

History of Sari-like drapery is traced back to the Indus Valley civilisation, which flourished during 2800–1800 BCE around the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent.[5][6] Cotton was first cultivated and woven on the Indian subcontinent around the 5th millennium BCE.[21] Dyes used during this period are still in use, particularly indigo, lac, red madder and turmeric.[22] Silk was woven around 2450 BCE and 2000 BCE.[23][24]

The word sari evolved from śāṭikā (Sanskrit: शाटिका) mentioned in earliest Hindu literature as women’s attire.[25][17] The sari or śāṭikā evolved from a three-piece ensemble comprising the antarīya, the lower garment; the uttarīya; a veil worn over the shoulder or the head; and the stanapatta, a chestband. This ensemble is mentioned in Sanskrit literature and Buddhist Pali literature during the 6th century BCE.[26] Ancient antariya closely resembled the dhoti wrap in the «fishtail» version which was passed through the legs, covered the legs loosely and then flowed into long, decorative pleats at front of the legs.[4][27][28] It further evolved into Bhairnivasani skirt, today known as ghagri and lehenga.[29] Uttariya was a shawl-like veil worn over the shoulder or head. It evolved into what is known today known as dupatta and ghoonghat.[30] Likewise, the stanapaṭṭa evolved into the choli by the 1st century CE.[18][19][31][32]

The ancient Sanskrit work Kadambari by Banabhatta and ancient Tamil poetry, such as the Silappadhikaram, describes women in exquisite drapery or sari.[11][33][34][35] In ancient India, although women wore saris that bared the midriff, the Dharmasastra writers stated that women should be dressed such that the navel would never become visible, which may have led to a taboo on navel exposure at some times and places.[36][37][5][38]

It is generally accepted that wrapped sari-like garments for lower body and sometimes shawls or scarf like garment called ‘uttariya’ for upper body, have been worn by Indian women for a long time, and that they have been worn in their current form for hundreds of years. In ancient couture the lower garment was called ‘nivi’ or ‘nivi bandha’, while the upper body was mostly left bare.[17] The works of Kalidasa mention the kūrpāsaka, a form of tight fitting breast band that simply covered the breasts.[17] It was also sometimes referred to as an uttarāsaṅga or stanapaṭṭa.[17]

Poetic references from works like Silappadikaram indicate that during the Sangam period in ancient Tamil Nadu in southern India, a single piece of clothing served as both lower garment and head covering, leaving the midriff completely uncovered.[33] Similar styles of the sari are recorded paintings by Raja Ravi Varma in Kerala.[39] Numerous sources say that everyday costume in ancient India until recent times in Kerala consisted of a pleated dhoti or (sarong) wrap, combined with a breast band called kūrpāsaka or stanapaṭṭa and occasionally a wrap called uttarīya that could at times be used to cover the upper body or head.[17] The two-piece Kerala mundum neryathum (mundu, a dhoti or sarong, neryath, a shawl, in Malayalam) is a survival of ancient clothing styles. The one-piece sari in Kerala is derived from neighbouring Tamil Nadu or Deccan during medieval period based on its appearance on various temple murals in medieval Kerala.[40][5][6][41]

Early Sanskrit literature has a wide vocabulary of terms for the veiling used by women, such as Avagunthana (oguntheti/oguṇthikā), meaning cloak-veil, Uttariya meaning shoulder-veil, Mukha-pata meaning face-veil and Sirovas-tra meaning head-veil.[42] In the Pratimānātaka, a play by Bhāsa describes in context of Avagunthana veil that «ladies may be seen without any blame (for the parties concerned) in a religious session, in marriage festivities, during a calamity and in a forest«.[42] The same sentiment is more generically expressed in later Sanskrit literature.[43] Śūdraka, the author of Mṛcchakatika set in fifth century BCE says that the Avagaunthaha was not used by women everyday and at every time. He says that a married lady was expected to put on a veil while moving in the public.[43] This may indicate that it was not necessary for unmarried females to put on a veil.[43] This form of veiling by married women is still prevalent in Hindi-speaking areas, and is known as ghoonghat where the loose end of a sari is pulled over the head to act as a facial veil.[44]

Based on sculptures and paintings, tight bodices or cholis are believed to have evolved between the 2nd century BCE to 6th century CE in various regional styles.[45] Early cholis were front covering tied at the back; this style was more common in parts of ancient northern India. This ancient form of bodice or choli are still common in the state of Rajasthan today.[46] Varies styles of decorative traditional embroidery like gota patti, mochi, pakko, kharak, suf, kathi, phulkari and gamthi are done on cholis.[47] In Southern parts of India, choli is known as ravikie which is tied at the front instead of back, kasuti is traditional form of embroidery used for cholis in this region.[48] In Nepal, choli is known as cholo or chaubandi cholo and is traditionally tied at the front.[49]

Red is the most favoured colour for wedding saris, which are the traditional garment choice for brides in Hindu wedding.[50] Women traditionally wore various types of regional handloom saris made of silk, cotton, ikkat, block-print, embroidery and tie-dye textiles. Most sought after brocade silk saris are Banasari, Kanchipuram, Gadwal, Paithani, Mysore, Uppada, Bagalpuri, Balchuri, Maheshwari, Chanderi, Mekhela, Ghicha, Narayan pet and Eri etc. are traditionally worn for festive and formal occasions.[51] Silk Ikat and cotton saris known as Patola, Pochampally, Bomkai, Khandua, Sambalpuri, Gadwal, Berhampuri, Bargarh, Jamdani, Tant, Mangalagiri, Guntur, Narayan pet, Chanderi, Maheshwari, Nuapatn, Tussar, Ilkal, Kotpad and Manipuri were worn for both festive and everyday attire.[52] Tie-dyed and block-print saris known as Bandhani, Leheria/Leheriya, Bagru, Ajrakh, Sungudi, Kota Dabu/Dabu print, Bagh and Kalamkari were traditionally worn during monsoon season.[53] Gota Patti is popular form of traditional embroidery used on saris for formal occasions, various other types of traditional folk embroidery such mochi, pakko, kharak, suf, kathi, phulkari and gamthi are also commonly used for both informal and formal occasion.[54][55] Today, modern fabrics like polyester, georgette and charmeuse are also commonly used.[56][57][58]

Styles of draping[edit]

There are more than 80 recorded ways to wear a sari.[59] The most common style is for the sari to be wrapped around the waist, with the loose end of the drape to be worn over the shoulder, baring the midriff.[60] However, the sari can be draped in several different styles, though some styles do require a sari of a particular length or form. Ṛta Kapur Chishti, a sari historian and recognised textile scholar, has documented 108 ways of wearing a sari in her book, ‘Saris: Tradition and Beyond’. The book documents the sari drapes across fourteen states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh.[61] The French cultural anthropologist and sari researcher Chantal Boulanger categorised sari drapes in the following families:[5]

The Sari Series,[62] a non-profit project created in 2017 is a digital anthology[63] documenting India’s regional sari drapes providing over 80 short films on how-to-drape the various styles.

- Nivi sari – style originally worn in Deccan region; besides the modern nivi, there is also the Nauvari, kaccha or kasta nivi, where the pleats are passed through the legs and tucked into at the back. This allows free movement while covering the legs.

- Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarati, Rajasthani – It is worn similar to nivi style but with loose end of sari aanchal or pallu placed in the front, therefore this style is known as sidha anchal or sidha pallu. After tucking in the pleats similar to the nivi style, the loose end is taken from the back, draped across the right shoulder, and pulled across to be secured in the back. This style is also worn by Punjabi and Sindhi Hindus.

- Bengali and Odia style is worn with single box-pleat.[64] Traditionally the Bengali style is worn with single box pleat where the sari is wrapped around in an anti-clockwise direction around the waist and then a second time from the other direction. The loose end is a lot longer and that goes around the body over the left shoulder. There is enough cloth left to cover the head as well.

- Himalayan — Kulluvi Pattu is traditional form of woolen sari worn in Himachal Pradesh, similar variation is also worn in Uttarakhand.

- Nepali: Nepal has many different varieties of draping sari, today the most common is the Nivi drape. The traditional Newari sari drape is, folding the sari till it is below knee length and then wearing it like a nivi sari but the pallu is not worn across the chest and instead is tied around the waist and leaving it so it drops from waist to the knee, instead the pallu or a shawl is tied across the chest, by wrapping it from the right hip and back and is thrown over the shoulders. Saris are worn with blouse that are thicker and are tied several times across the front. The Bhojpuri and Awadhi speaking community wears the sari sedha pallu like the Gujrati drape. The Mithila community has its own traditional Maithili drapes like the madhubani and purniea drapes but today those are rare and most sari is worn with the pallu in the front or the nivi style.[65] The women of the Rajbanshi communities traditionally wear their sari with no choli and tied below the neck like a towel but today only old women wear it in that style and the nivi and the Bengali drapes are more popular today. The Nivi drape was popularized in Nepal by the Shah royals and the Ranas.

- Nauvari and Kasta: this drape is worn similar to ancient form of navi sari worn in «Kacche» style where pleats in the front are tucked in the back, though there are many regional and societal variations. The style worn by Brahmin women differs from that of the Marathas. The style also differs from community to community. This style is popular in Maharashtra and Goa.

- Madisar – this drape is typical of Iyengar/Iyer Brahmin ladies from Tamil Nadu. Traditional Madisar is worn using 9 yards sari.[66] The Parsi ‘gara’ is a quintessence of embroidery, art and history, and it has a Chinese link

- Pin Kosuvam — this is the traditional Tamil Nadu style

- The Brahmika sari was introduced to Bengal by Jnanadanandini Devi after her tour in Bombay in 1870. Jnanadanandini improvised upon the sari style worn by Parsi and Gujarati women, which came to be known as Brahmika style.[67]

- Kodagu style – this drape is confined to ladies hailing from the Kodagu district of Karnataka. In this style, the pleats are created in the rear, instead of the front. The loose end of the sari is draped back-to-front over the right shoulder, and is pinned to the rest of the sari.

- Gobbe Seere – This style is worn by women in the Malnad or Sahyadri and central region of Karnataka. It is worn with 18 molas sari with three-four rounds at the waist and a knot after crisscrossing over shoulders.

- Karnataka – In Karnataka, apart from traditional Nivi sari, sari is also worn in «Karnataka Kacche» drape, kacche drape which shows nivi drape in front and kacche in back, there are Four kacche styles known in Karnataka — «Hora kacche«, «Melgacche» ,»Vala kacche» or «Olagacche» and « Hale Kacche«.

- Kerala sari style – the two-piece sari, or Mundum Neryathum, worn in Kerala. Usually made of unbleached cotton and decorated with gold or coloured stripes and/or borders. Also the Kerala sari, a sort of mundum neryathum.

- Kunbi style or denthli: Goan Kunbis and Gauda, and those of them who have migrated to other states use this way of draping sari or kappad, this form of draping is created by tying a knot in the fabric below the shoulder and a strip of cloth which crossed the left shoulder was fasten on the back.[68]

- Riha-Mekhela, Kokalmora, Chador/Murot Mora Gamusa — This style worn in Assam is a wrap around style cloth similar to other wrap-around from other parts of South-East Asia and is actually very different in origin from the Mainland Indian sari. It is originally a four-set of separate garments (quite dissimilar to the sari as it is a single cloth) known Riha-Mekhela, Kokalmora, Chador/Murot Mora Gamusa. The bottom portion, draped from the waist downwards is called Mekhela. The Riha or Methoni is wrapped and often secured by tying them firmly across the chest, covering the breasts originally but now it is sometimes replaced by the influence of immigrant Mainland Indian styles which is traditionally incorrect. The Kokalmora was used originally to tie the Mekhela around the waist and keep it firm.

- Innaphi and Phanek — This style of clothing worn in Manipur is also worn with three-set garment known as Innaphi Viel, Phanek lower wrap and long sleeved choli. It is somewhat similar to the style of clothing worn in Assam.

- Jainsem — It is a Khasi style of clothing worn in Khasi which is made up of several pieces of cloth, giving the body a cylindrical shape.

Historic photographs and regional styles[edit]

-

Lakshmi depicted in ancient variation of sari, 1st century BCE

-

Women in choli (blouse) and antariya c. 320 CE, Gupta Empire

-

Woman dressed in sari, deccan, ca. 1600

-

Women dressed in sari, deccan, ca. 1565

-

Women dressed in sari, ca. 1600

-

Girl in Gujarati sari; in this style, the loose end is worn on the front

-

Woman in Tamil sari; in this style, the loose end is wrapped around the waist

-

Girl in Bengali sari; in this style sari is worn without any pleats

-

Kandyan Sinhalese lady wearing a traditional Kandyan sari (osaria)

-

-

A member of the royal family of Mysore in Mysore sari

-

Women depicted in Melgacche drape, from Karnataka kacche , Kannada manuscript 16th–17th century

-

Sari draping style of Karnataka, Hale Kacche sari/ಹಳೆಕಚ್ಚೆ ಸೀರೆ.

-

Women in Nepali style sari, 1941

Nivi style[edit]

Women dressed in nivi sari entertaining couple, Deccan, 1591 CE

Maharani Ourmilla Devi of Jubbal in modern style of Nivi sari, 1935.

The Nivi in most common style of sari worn today, which originated in Deccan region.[9][10] In the Deccan region the Nivi existed in two styles, a style similar to modern Nivi and the second style worn with front pleats of Nivi tucked in the back.[17]

The increased interactions during colonial era saw most women from royal families come out of purdah in the 1900s. This necessitated a change of dress. Maharani Indira Devi of Cooch Behar popularised the chiffon sari. She was widowed early in life and followed the convention of abandoning her richly woven Baroda shalus in favour of the unadorned mourning white as per tradition. Characteristically, she transformed her «mourning» clothes into high fashion. She had saris woven in France to her personal specifications, in white chiffon, and introduced the silk chiffon sari to the royal fashion repertoire.[69]