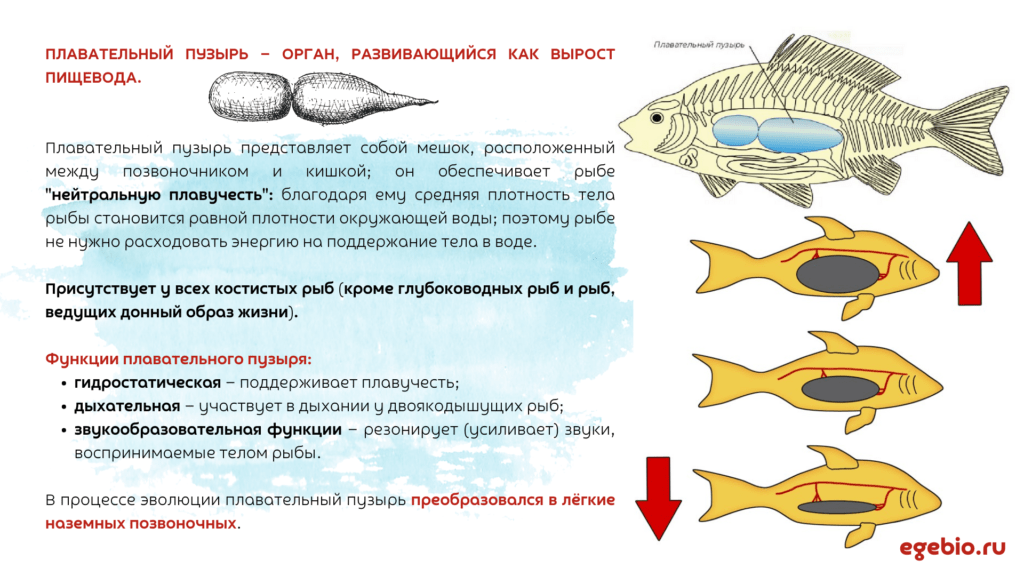

Плавательный пузырь

Сначала давайте вспомним, что такое “плавательный пузырь” и какие функции он выполняет.

Пла́вательный пузы́рь — особый орган, характерный только для костных рыб. Расположен в полости тела под позвоночником и позволяет рыбе не утонуть под собственной тяжестью.

- В ходе эмбрионального развития образуется как спинной вырост кишечной трубки.

Плавательный пузырь состоит из одной или двух камер, заполненных смесью газов, похожей на воздух.

- Основная функция плавательного пузыря — обеспечение нулевой плавучести: он компенсирует вес костей и других тяжёлых частей тела и приближает среднюю плотность тела к плотности воды

В результате рыбе не надо тратить энергию на поддержание тела на нужной глубине (тогда как акулы, у которых плавательного пузыря нет, вынуждены поддерживать глубину погружения постоянным активным движением).

- Однако сжимаемость газа делает равновесие неустойчивым: при погружении рыбы давление воды возрастает, пузырь уменьшается и рыба опускается ещё сильнее; аналогично при всплывании пузырь расширяется и рыбу выталкивает к поверхности.

- Чтобы этому препятствовать, организм рыбы регулирует количество газа в пузыре газовыми железами (густыми скоплениями капилляров), где кровь выделяет или поглощает кислород

- У рыб, способных к быстрым вертикальным перемещениям, пузыря нет, так как эта регулировка не успевала бы подстраиваться под изменения давления и при быстром всплытии раздувание пузыря могло бы быть опасным.

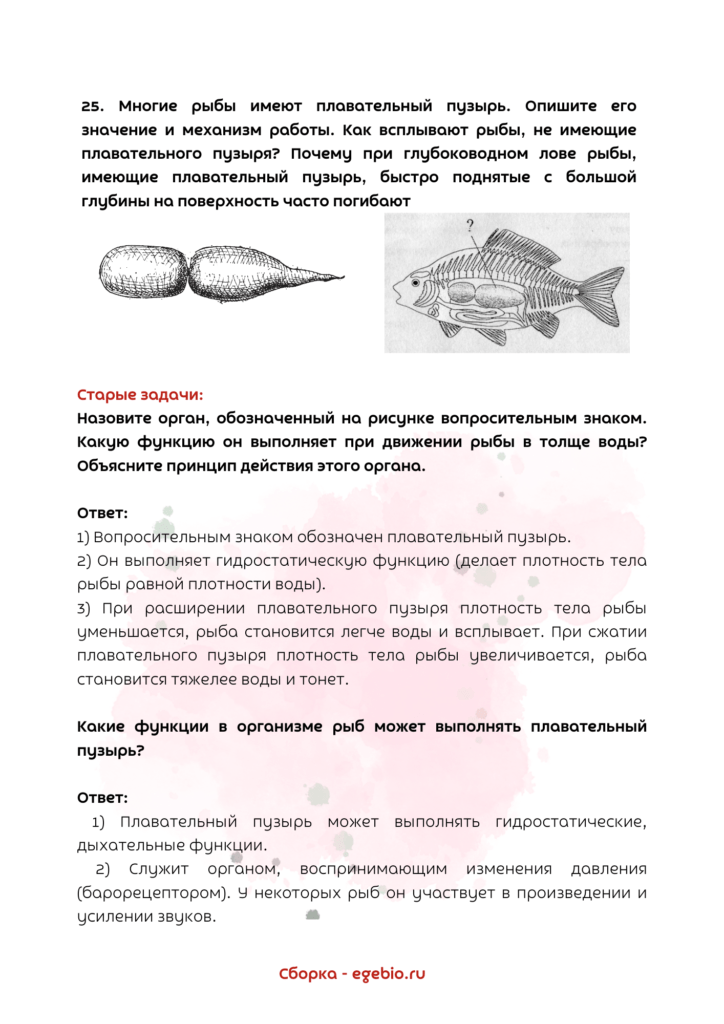

Рыбы, имеющие воздушную камеру, делятся на два типа:

1.Открытопузырные способны контролировать наполнение при помощи специального канала, имеющего сообщение с кишечником.

-

- Они могут быстрее всплывать и погружаться, а при необходимости захватывают воздух ртом из атмосферы.

- К этому типу относится бо́льшая часть костных рыб, например: карп и щука.

2. Закрытопузырные имеют герметичную камеру, не имеющую прямого сообщения с внешним миром.

-

- Уровень газа контролируется с помощью кровеносной системы. Воздушный пузырь у рыб оплетён сетью капилляров (красное тело), которые способны медленно поглощать или отдавать воздух.

- Представители этого типа — треска, окунь. Не могут позволить себе быстрого изменения глубины. При мгновенном извлечении из воды такую рыбу сильно раздувает.

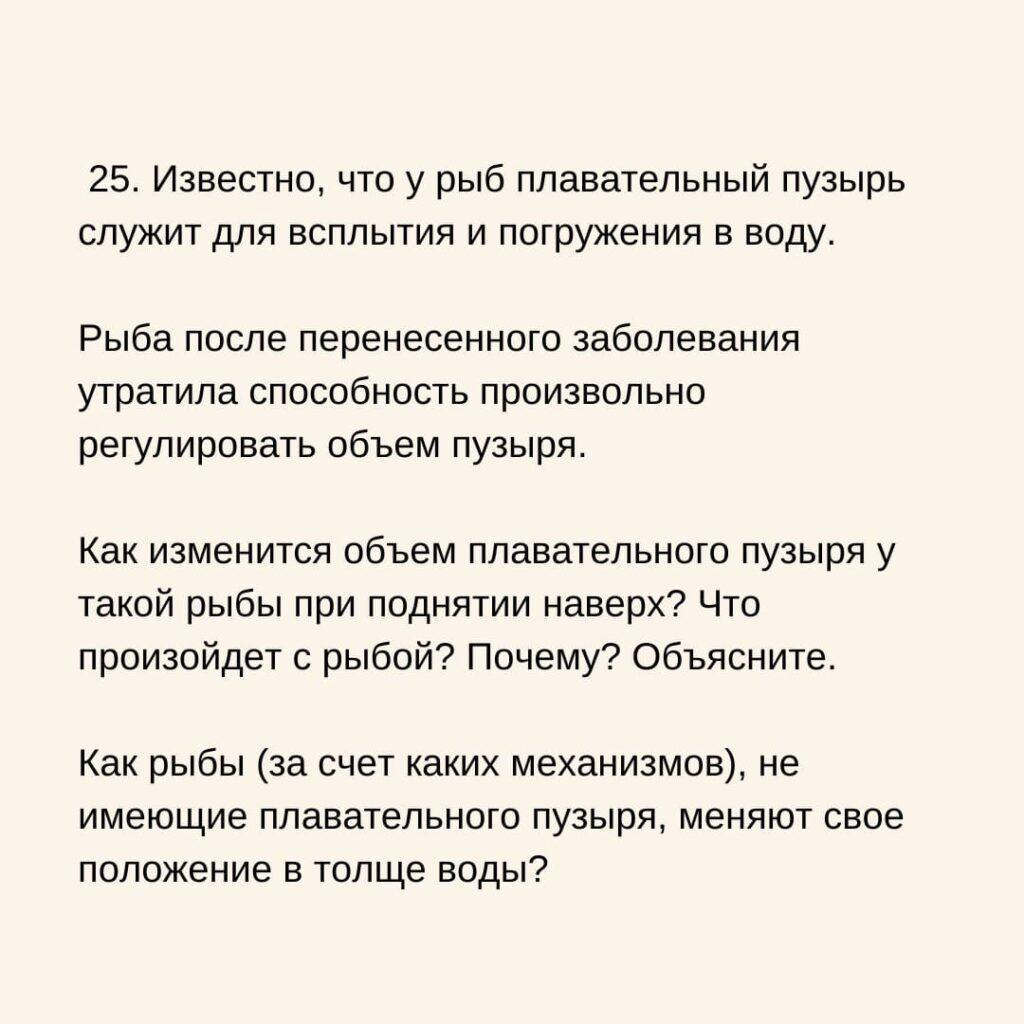

А ТЕПЕРЬ ДАВАЙТЕ ПОДУМАЕМ КАК РЫБА МОЖЕТ МЕНЯТЬ ГЛУБИНУ, ЕСЛИ У НЕЕ НЕТ ПЛАВАТЕЛЬНОГО ПУЗЫРЯ ИЛИ С ЕГО ГИДРОСТАТИЧЕСКОЙ ФУНКЦИЕЙ ЧТО-ТО СЛУЧИЛОСЬ

Какие функции в организме рыб может выполнять плавательный пузырь?

Спрятать пояснение

Пояснение.

1) Плавательный пузырь может выполнять гидростатические, дыхательные функции.

2) Служит органом, воспринимающим изменения давления (барорецептором). У некоторых рыб он участвует в произведении и усилении звуков.

Спрятать критерии

Критерии проверки:

| Критерии оценивания ответа на задание С3 | Баллы |

|---|---|

| Ответ включает все названные выше элементы и не содержит биологических ошибок | 2 |

| Ответ включает 1 из названных выше элементов и не содержит биологических ошибок, ИЛИ ответ включает 2 из названных выше элементов, но содержит не грубые биологические ошибки | 1 |

| Ответ неправильный | 0 |

| Максимальное количество баллов | 2 |

При описании плавательного пузыря часто отдельно упоминают плавательный пузырь угрей родов Anguilla и Conger (рисунок D). Действительно, в его строении есть ряд интересных особенностей. Имея связь с кишечником, он, однако, функционирует как плавательный пузырь закрытого типа. В чем же это проявляется? Дело в том, что воздушный канал у угрей этих родов расширен и функционально соответствует зоне овала — через его стенки происходит резорбция газов в кровь, синтез же газов осуществляется в единственной крупной вытянутой камере, снабженной мощной газовой железой. Помимо этого, с плавательным пузырем закрытого типа его сближает особенность кровообращения и состав наполняющих газов.

Говоря о разнообразии строения плавательного пузыря и особенностях его связи с внешней средой нельзя не упомянуть о плавательном пузыре сельдевых (сем. Clupeidae). Особенности его строения связаны с особенностями биологии этих рыб, которым свойственны значительные и резкие вертикальные миграции. Так, типичный представитель сельдевых тихоокеанская сельдь Clupea pallasii совершает подобные миграции из глубин моря в поверхностные слои вслед за планктоном, которым она питается. При таких перемещениях объем газа в плавательном пузыре резко увеличивается за счет снижения внешнего давления, что в обычном случае могло бы привести к повреждению тканей рыбы (нечто подобное мы наблюдаем при ловле рыб с глубины — часто такие поимки сопровождаются выпячиванием плавательного пузыря через рот рыбы). Чтобы такого не происходило, в процессе эволюции сельди приобрели дополнительное отверстие, расположенное в районе анального и соединяющее плавательный пузырь с внешней средой. Через него и происходит «стравливание» лишнего воздуха, причем этот процесс может контролироваться самой рыбой с помощью имеющегося здесь сфинктера.

Подробнее о функционировании плавательного пузыря я расскажу в одном из следующих постов.

Внешнее строение рыб

Рыбы — это водные животные. Для того, чтобы активно передвигаться в водной среде тело рыб имеет обтекаемую форму.

Рыбы обитают в пресных и соленых водоемах

Тело рыб можно разделить на:

- голову

- туловище

- и хвост

Тело рыб состоит из головы, туловища и хвоста

Границей между головой и туловищем служит задний край жаберных крышек, границей между туловищем и хвостом — анальный плавник.

Insert Flash

Сверху тело рыб покрыто кожей, которая состоит из:

- кориума или дермы

- и многослойного эпидермиса (как у всех позвоночных животных).

В эпидермисе есть многочисленные слизистые железы, сверху эпидермис у большинства рыб покрыт чешуей.

Тело большинства рыб покрыто чешуей

Обтекаемая форма тела, слизистые железы и чешуя помогают рыбам быстро и легко перемещаться в воде.

Передвигаются они с помощью изгибов туловища и с помощью парных грудных и брюшных плавников, которые в основном отвечают за вертикальное перемещение, а также непарного хвостового плавника, который выполняет функцию руля.

Парные плавники рыб — грудные и брюшные, непарные — спинной, анальный и хвостовой

Также к непарным плавникам у рыб относится спинной и анальный плавники, которые стабилизируют тело рыб в вертикальном положении.

Плавники:

- парные грудные

- парные брюшные

- непарный спинной (1 или несколько)

- непарный анальный

- непарный хвостовой

Опорно-двигательная система рыб

Insert Flash

У рыб хорошо развит скелет, который разделяется на:

1. осевой скелет, к которому относятся:

- позвоночник,

- череп или скелет головы

- и ребра

2. скелет конечностей, к которому относятся:

- скелет парных плавников (свободной части и поясов)

- и скелет непарных плавников.

Скелет рыб — на рисунке представлен скелет костной рыбы

Скелет рыб состоит из черепа, позвоночника, ребер и скелета парных и непарных плавников

У представителей класса Хрящевых рыб скелет состоит только из хрящевой ткани. У представителей класса Костных рыб в скелете присутствуют как хрящевая, так и костная ткань.

Позвоночник выполняет опорную и защитную функции — спинной мозг защищен дугами позвонков. Позвоночник состоит из двух отделов — туловищного и хвостового. Позвонки туловищного отдела позвоночника имеют боковые отростки, к которым прикрепляются ребра.

Скелет головы представлен черепной коробкой, с которой соединены челюсти и жаберные дуги, а у костных рыб и жаберные крышки. У хрящевых рыб жаберных крышек нет.

Пищеварительная система рыб

Пищеварительная система рыб

Пищеварительная система состоит из рта, глотки, пищевода, желудка и кишечника, в который открываются протоки печени и желчного пузыря, а также поджелудочной железы. Кишечник заканчивается анальным отверстием, которое открывается перед анальным плавником.

Плавательный пузырь есть только у костных рыб

У рыб есть плавательный пузырь, который представляет собой вырост кишечной трубки. Плавательный пузырь заполнен газами, он может расширяться и сжиматься. При этом меняется удельная плотность тела и рыба может перемещаться в толще воды в вертикальном направлении. Плавательный пузырь есть только у костных рыб, у хрящевых его нет.

Дыхательная система рыб

Рыбы дышат с помощью жабр

Дыхание рыб осуществляется с помощью жабр. Вода поступает в рот, затем из глотки вода проходит через жабры во внешнюю среду, при этом кровеносные сосуды, расположенные в жаберных лепестках насыщаются кислородом.

Кровеносная система рыб

Кровеносная система рыб замкнутого типа

Кровеносная система имеет один круг кровообращения у всех рыб, кроме двоякодышащих. Есть двухкамерное сердце, состоящее из предсердия и желудочка.

Insert Flash

Нервная система рыб

Нервная система состоит из:

- центрального отдела, которые представлен головным и спинным мозгом и

- периферического отдела, состоящего из черепно-мозговых и спинномозговых нервов.

Головной мозг у рыб, как и у всех позвоночных животных состоит из пяти отделов.

Нервная система рыб состоит из головного и спинного мозга и отходящих от них нервов

Хорошо развиты обонятельные доли переднего мозга, так как для рыб очень важную роль играют органы химического чувства — обоняния и вкуса. Зрительные центры располагаются в среднем мозге.

Также хорошо развит мозжечок, который отвечает за разнообразные движения. Есть органы боковой линии, позволяющие рыбам определять направление движения воды. Есть органы равновесия и слуха.

Выделительная система рыб

Выделительная система рыб состоит из почек, мочеточников и мочевого пузыря.

Выделительная система представлена парными лентовидными почками, мочеточниками и мочевым пузырем, который открывается мочеиспускательным отверстием, которое расположено рядом с анальным отверстием.

Половая система рыб

Большинство рыб раздельнополы, у самцов есть два семенника, у самок — два яичника. Самки выметывают яйцеклетки (икринки) в воду, самцы — сперматозоиды. Оплодотворение происходит во внешней среде.

Яйцеклетки рыб — икринки

У многих хрящевых рыб и у некоторых костных оплодотворение внутреннее, самки рождают мальков.

Систематика рыб

В настоящий момент известно около 30 тысяч видов рыб. Систематика рыб достаточно сложна, мы рассмотрим несколько упрощенную схему. В настоящее время в разных источниках можно встретить различные варианты систематики.

Классы хрящевые и костные рыбы

К надклассу рыб относятся два класса — это Хрящевые рыбы и Костные рыбы.

Скелет хрящевых рыб, как следует из названия состоит только из хрящевой ткани.

К хрящевым рыбам относятся акулообразные, скаты и химерообразные

К классу Хрящевых рыб относятся:

- отряд Акулообразные,

- отряд Скаты

- и отряд Химерообразные.

Для хрящевых рыб характерны следующие черты — у них нет плавательного пузыря, нет жаберных крышек.

Хрящевые рыбы — акулы и скаты

Отряд Костные рыбы наиболее многочисленный, к нему относится до 96% видов рыб.

К костным рыбам относятся подклассы Лучеперые и Лопастеперые

ХРЯЩЕВЫЕ РЫБЫ

Класс Хрящевые рыбы. Сравнительно немногочисленная группа рыб (около 730 видов),скелет которых пожизненно остается хрящевым. Форма тела чаще веретенообразная. Класс называется так из-за наличия хрящевого скелета (рис. 1), костной ткани у них нет. Например, челюсти акулы, как и ее скелет, тоже состоят из хряща (рис. 2).

Рис. 1. Хрящевой скелет (Источник)

Рис. 2. Акула (Источник)

Хрящ может быть пропитан солями кальция. Подвижных жаберных крышек нет, вместо них жаберные щели, расположенные на брюшной части тела рыбы или по бокам тела (рис. 3).

Рис. 3. Пример жаберных щелей китовой акулы (Источник)

Отсутствует плавательный пузырь. Кожа бывает голой или покрытой чешуями, которые по строению и составу напоминают зубы, они так и называются – кожные зубы.

Класс включает в себя три отряда: Акулы, Скаты, Химерообразные (рис. 4).

Рис. 4. Отряды (Источник)

Отряд акулы

Форма тела: удлиненная торпедообразная форма тела.

Длина: от 20 см до 20 м (рис. 5).

Кожа: шероховатая, покрыта зубцами и чешуями.

Плавники: парные брюшные и грудные плавники расположены горизонтально, обеспечивают движение рыбы вверх или вниз. Движение вперед и повороты обеспечиваются изгибом хвоста или тела.

Органы чувств: глаза располагаются по бокам головы, зрение черно-белое. Обладают сильным обонянием, чувствуют малейшие колебания воды и так узнают про добычу на большом расстоянии.

Оплодотворение: внутреннее, размножаются живорождением или яйцеживорождением.

Некоторые акулы могут нападать на людей. Большинство акул – морские рыбы, но некоторые заплывают и в пресные водоемы. Один вид живет постоянно в пресноводном озере Никарагуа (рис. 6). Некоторые виды акул едят люди, чаще всего японцы, особенно ценными считаются печень и плавники. Кожа применяется в промышленности.

Рис. 5. Акула тигровая (Источник)

Рис. 6. Никарагуанская пресноводная акула (Источник)

Отряд скаты

Форма тела: уплощенное в спинно-брюшном направлении.

Плавники: расширенные грудные плавники по бокам, хвостовой плавник имеет вид длинного тонкого хлыста.

Размеры: относительно крупные рыбы, некоторые достигают 6–7 м в ширину, масса может быть в районе 2,5 т (рис.7). Самые маленькие скаты в длину могут быть около 12 см.

Глаза и рот: у донных видов глаза расположены на верхней стороне головы, у пелагических – по бокам. Рот в поперечном положении и жаберные щели находятся на брюшной стороне тела.

Кожа: голая или с кожными зубами, имеются железистые клетки, выделяющие слизь.

Оплодотворение: внутреннее, размножаются живорождением или яйцеживорождением.

Представители вида ведут донный образ жизни, крупные скаты могут обитать в толще воды. Большинство скатов – морские, но есть и пресноводные виды. Некоторые небольшие пресноводные скаты содержатся в аквариумах.

Рис. 7. Скат (Источник)

Отряд химерообразные

Химерообразные – это немногочисленная и своеобразная группа глубоководных рыб.

Форма тела: имеется мощный передний отдел и постепенно сужается к хвосту.

Длинна: от 60 см до 2 м.

Плавники: хвостовой плавник тонкий и заканчивается тонким нитевидным придатком.

Кожа: голая и лишенная чешуй.

Оплодотворение: внутреннее, размножаются путем откладки яиц.

Всего известно около 30 видов химерообразных рыб. Наиболее изучена европейская химера, обитающая в Баренцевом море на глубинах более 1000 м (рис. 8). В Тихом и Атлантическом океане обитают носатые химеры (рис. 9).

Рис. 8. Европейская химера (Источник)

Рис. 9. Носатая химера (Источник)

КОСТНЫЕ РЫБЫ

Класс Костные рыбы включает подавляющее большинство представителей надкласса

Рыбы (около 20 тыс. видов), населяющих пресные и соленые водоемы. Свое название класса говорит о присутствии костного скелета, тело покрыто костной чешуей или пластинами, кожных зубов нет, в отличие от хрящевых рыб, жаберная полость прикрыта жаберными крышками, которые подвижны, имеется плавательный пузырь, который у донных и малоподвижных форм может исчезать (рис. 1).

Рис. 1. Признаки костных рыб

Именно у костных рыб впервые в эволюции появляются настоящие легкие. Рыбы, имеющие и жабры и легкие называются двоякодышащими. Большая часть этой некогда огромной группы вымерла в триасовом периоде, однако существует и несколько современных групп двоякодышащих (рис. 2).

Рис. 2. Австралийский рогозуб

Всего существует около 20 тысяч видов костных рыб, хотя об этом не очень часто говорят, но костные рыбы – это самый многочисленный класс позвоночных. Особенности экологии, строения и физиологии отдельных видов позволяют разделить все это громадное многообразие на несколько десятков отрядов.

Мы с вами обсудим лишь 6 самых значимых из них: Осетрообразные, Сельдеобразные, Лососеобразные, Карпообразные, Окунеобразные, Целакантообразные.

Отряд Осетрообразные

Осетрообразные – это немногочисленная группа, сохранившая ряд древних признаков, которые подчеркивают их сходство с хрящевыми рыбами. Так, у этих рыб в течение всей жизни сохраняется хорда, а скелет костно-хрящевой. Тело удлиненное, голова начинается уплощенным рылом (рис. 3).

Рис. 3. Осетрообразные

Представители семейства осетровых встречаются в основном в умеренных широтах Северного полушария. Взрослые рыбы проводят всю жизнь в море, а в реки заходят только для нереста, однако существуют и полностью пресноводные формы.

Пищей большинства осетровых служат водные беспозвоночные, некоторые виды питаются мелкой или даже крупной рыбой.

Мясо и особенно икра осетровых чрезвычайно высоко ценится как деликатесы (рис. 4). Из-за этого осетровые всегда подвергались браконьерскому лову. Строительство гидроэлектростанций привело во многих реках почти к полному вымиранию осетровых.

Дело в том, что взрослые рыбы не могут подняться по реке вверх через плотину (рис. 5).

Рис. 4. Черная икра осетровых

Рис. 5. Гидроэлектростанция

Отряд Сельдеобразные

Отряд включает в себя рыб с вытянутым телом, слегка сжатым с боков (рис. 6). Парные и не парные плавники мягкие, боковая линия обычно не заметна. Длина тела сельдеобразных обычно от 5 до 75 сантиметров.

Рис. 6. Сельдеобразные

Большинство сельдеобразных – это морские рыбы, однако есть и проходные виды, а некоторые представители освоили и пресные водоемы тоже. Наиболее известно из отряда семейство Сельдевые. Это морские рыбы мелких и средних размеров. Огромное промысловое значение имеет сельдь, сардина и килька (рис. 7).

Рис. 7. Промысловое значение сельдевых

Отряд Лососеобразные

Включает рыб, сходных с сельдевыми, длиной от 2,5 см до 1,5 м (рис. 8). Большинство представителей семейства лососевых – это проходные рыбы, однако есть и пресноводные формы.

Рис. 8. Лососеобразные

Часто при вхождении в реки у лососевых появляется яркий брачный наряд (рис. 9). В это время лососевые не питаются, и существуют лишь благодаря запасу питательных веществ, накопленных в море. После нереста рыбы часто гибнут.

Рис. 9. Брачный наряд лососевых

Все лососевые – это промысловые рыбы, высоко ценимые за вкусное мясо и икру. Многих лососеобразных разводят в специальных рыбоводческих хозяйствах. Необходимо помнить, что разнообразие отряда лососеобразные отнюдь не исчерпывается семейством Лососевые (рис. 10).

Рис. 10. Промысел лососевых

Отряд Карпообразные

Представители этого отряда весьма сходны с сельдеобразными, но отличаются от них своеобразным строением позвоночника. Число видов этого отряда составляет около 15 процентов от общего разнообразия костных рыб (рис. 11).

Рис. 11. Карпообразные

Среди карпообразных встречаются как растительноядные, так всеядные и даже хищные рыбы. К хищным рыбам принадлежат, например, пиранья и электрический угорь (рис. 12).

Рис. 12. Пиранья и электрический угорь

Промысловое значение карпообразных огромно, ряд видов искусственно разводят в прудовых хозяйствах (рис. 13).

Рис. 13. Рыбные фермы

Известнейшей декоративной прудовой рыбой является карп кои (рис. 14). Некоторые тропические карпообразные с красивой и яркой окраской стали объектами для содержания в аквариумах.

Рис. 14. Японский карп кои

Отряд Окунеобразные

Окунеобразные – самая многочисленная по видовому составу группа рыб. Он включает в себя более 9 тысяч видов (рис. 15).

Рис. 15. Окунеобразные

Распространены окунеобразные в водоемах всех материков, во всех морях и океанах. Длина тела – от 1 см до 5 метров. Масса – от долей грамма до тонны и более. Например, луна-рыба может иметь длину до 3 метров и массу почти до полутора тонн (рис. 16).

Рис. 16. Рыба-луна

Характерной особенностью всего отряда является наличие 2-х спинных плавников с острыми колючками. Наиболее известно семейство каменных окуней, собственно окуневых, ставридовых, зубатковых, бычков и парусников.

Очевидно, что многие представители отряда употребляются в пищу. Мелкие окуневые часто являются любимцами аквариумистов.

Отряд Целакантообразные

Целакантообразные – это очень небольшой, но очень важный отряд костных рыб. В современной фауне они представлены всего двумя видами. Эти последние представители кистеперых рыб вполне могут быть названы живыми ископаемыми (рис. 17). Дело в том, что некогда от подобных рыб произошли первые амфибии.

Рис. 17. Целакантообразные

Современные двоякодышащие

По происхождению двоякодышащие – это очень древняя группа рыб, появившаяся еще в девонском периоде. До наших дней сохранилось всего 2 семейства с 6 видами.

Двоякодышащие рыбы имеют как ряд примитивных черт, так и ряд черт, объединяющих их с амфибиями, самая главная такая черта – это, конечно, наличие легких. Наиболее известен из современных двоякодышащих род Протоптер (рис. 18).

Рис. 18. Протоптер

Протоптеры обитают во временных пересыхающих водоемах Африки. Замечательна способность этих рыб, впадая в анабиоз и теряя много воды, переживать пересыхание водоема.

Электрический угорь

Замечательным представителем отряда карпообразные является электрический угорь, кстати говоря, электрический угорь никакого отношения к настоящим угрям не имеет, он им не родственник.

Электрические угри обитают в водоемах с пониженным содержанием кислорода. У электрических угрей появилась способность использовать кислород воздуха, для этого рыба поднимается к поверхности воды и захватывает воздух ртом.

Электрический угорь способен создавать разряд напряжением до 350 Вольт, таким образом, эти рыбы защищаются или охотятся при помощи электричества (рис. 19).

Рис. 19. Электрический угорь

Удивительная история целаканта

Ископаемые останки целакантовых рыб известны начиная с девонского периода. После мелового периода никаких следов этой группы не обнаруживалось и она считалась полностью вымершей.

Рис. 20. Целакант

И вдруг пойманная в 1938 году рыба оказывается настоящим живым целакантом (рис. 20). Обнаружение подобного живого ископаемого, конечно же, стало сенсацией. Рыба была названа латимерией. Представьте себе: была найдена живая рыба, все родственники которой вымерли еще в эпоху динозавров.

-

Видео YouTube

- ТЕСТЫ

-

-

Зачем рыбам плавательный пузырь?

Рыбы — самая древняя, многочисленная и очень интересная группа позвоночных животных. За миллионы лет существования на Земле они идеально приспособились к узким, довольно однообразным условиям жизни — водной среде. Приспособленность рыб к жизни в воде проявилась в первую очередь во внешнем облике — обтекаемая форма тела, особенности покровов, обеспечивающие движение плавники. Характер среды определил развитие у рыб и специфическое строение внутренних органов.

Об одном из них и пойдет речь в этой статье.

У большинства современных рыб есть особый резервуар с воздухом – плавательный пузырь. Его объем полностью уравновешивает две силы – притяжение Земли, тянущее рыбу ко дну, и выталкивающее действие воды (силу Архимеда). Управляя его объемом, рыба и изменяет глубину на которой может плавать и зависать в толще воды.

Но как же это происходит?

- Плавательный пузырь — специфический орган, свойственный только костным рыбам. Он расположен в брюшной полости над кишечником и имеет форму полупрозрачного мешочка. Этот мешок состоит из одной или двух камер, наполнен газом и выполняет роль природного гидростатического датчика.

Действие «датчика» происходит следующим образом:

Если рыба опускается вниз, на глубину, давление воды на ее тело возрастает, пузырь сжимается и выталкивает из себя воздух. Это происходит автоматически и рыбке даже не приходится прилагать усилий, чтобы погрузиться вниз.

Естественно, все происходит наоборот, в том случае, когда рыба поднимается наверх — давление воды на тело спадает, и пузырь наполняется газом. Плавательный орган определенного размера способен без усилий удерживать рыбу на необходимой глубине.

Плавательный орган заполнен смесью газов, близким по составу к воздуху. В основном это кислород, углеводород и азот.

- Таким образом, основная функция плавательного пузыря – обеспечение лучшей плавучести рыб в определенной толще воды.

Пузырь пронизывают многочисленные нервные окончания, которые передают импульсы в центральную нервную систему. С помощью этих сигналов животное и может скорректировать свое передвижение, поскольку чувствует на какой глубине находится и какое давление испытывает извне.

В зависимости от типа плавательного пузыря, рыбы, его имеющие, делятся на две большие группы — открытопузырные и закрытопузырные.

-

У открытопузырчатых рыб пузырь напрямую связан с кишечником через специальный воздушный проток. Рыбы могут запросто заглатывать атмосферный воздух и так им образом контролировать объём плавательного пузыря. У них достаточно быстро меняется давление в данном органе, что и позволяет им продвигаться до необходимой глубины. К открытопузырным относятся карпообразные, сельдеобразные, щукообразные, а также более древние рыбы — двоякодыщащие и хрящекостные.

-

Закрытопузырчатые рыбы не имеют соединения между плавательным пузырем и кишечником, поэтому газовая регуляция происходит медленно через особую сеть капилляров на тонкой стенке. Таким образом, газы медленнее переходят из растворенного (в крови) состояния в газообразное, заполняя пузырь.

К закрытопузырным относятся окунеобразные, трескообразные, кефалеобразные и некоторые другие.

Интересно, что все закрытопузырные рыбы в зародышевом состоянии являются открытопузырными.

Есть у этого замечательного органа еще одна очень интересная общепризнанная функция. У некоторых костистых рыб плавательный пузырь может выполнять звукообразовательные и слуховые функции. Будучи хорошим резонатором, он усиливает окружающие звуки и помогает рыбам лучше слышать. А известны уникальные особи, которые с помощью такого пузыря могут издавать достаточно сильные звуки и подавать сигналы себе подобным!

Плавательного пузыря нет у хрящевых рыб — акул и скатов, возможно, потому, что их скелет, состоящий из хрящей, легче костного скелета других рыб. Обходятся без пузыря и быстроплавающие хищные рыбы, например, тунец и скумбрия. Мощная мускулатура этих хищников позволяет им быстро менять глубину и сопротивляться погружению.

У многих глубоководных и донных рыб плавательного пузыря тоже нет, да это и понятно – зачем он им нужен, если они никогда не всплывают на поверхность? Необходимую плавучесть им обеспечивает жир или невысокая плотность тканей тела.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Air bladder» redirects here. For the special effects technique, see Air bladder effect.

This article is about the organ found in many fish species. For the mathematical shape, see Fish bladder.

The swim bladder of a rudd

Internal positioning of the swim bladder of a bleak

S: anterior, S’: posterior portion of the air bladder

œ: œsophagus; l: air passage of the air bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish[1]) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their current water depth without having to expend energy in swimming.[2] Also, the dorsal position of the swim bladder means the center of mass is below the center of volume, allowing it to act as a stabilizing agent. Additionally, the swim bladder functions as a resonating chamber, to produce or receive sound.

The swim bladder is evolutionarily homologous to the lungs. Charles Darwin remarked upon this in On the Origin of Species.[3] Darwin reasoned that the lung in air-breathing vertebrates had derived from a more primitive swim bladder.

In the embryonic stages, some species, such as redlip blenny,[4] have lost the swim bladder again, mostly bottom dwellers like the weather fish. Other fish—like the opah and the pomfret—use their pectoral fins to swim and balance the weight of the head to keep a horizontal position. The normally bottom dwelling sea robin can use their pectoral fins to produce lift while swimming.

The gas/tissue interface at the swim bladder produces a strong reflection of sound, which is used in sonar equipment to find fish.

Cartilaginous fish, such as sharks and rays, do not have swim bladders. Some of them can control their depth only by swimming (using dynamic lift); others store fats or oils with density less than that of seawater to produce a neutral or near neutral buoyancy, which does not change with depth.

Structure and function[edit]

Swim bladder from a bony (teleost) fish

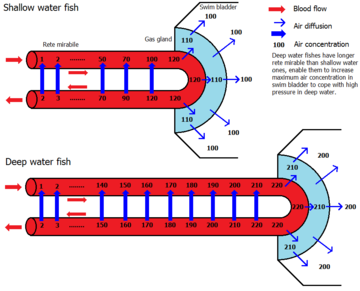

The swim bladder normally consists of two gas-filled sacs located in the dorsal portion of the fish, although in a few primitive species, there is only a single sac. It has flexible walls that contract or expand according to the ambient pressure. The walls of the bladder contain very few blood vessels and are lined with guanine crystals, which make them impermeable to gases. By adjusting the gas pressurising organ using the gas gland or oval window, the fish can obtain neutral buoyancy and ascend and descend to a large range of depths. Due to the dorsal position it gives the fish lateral stability.

In physostomous swim bladders, a connection is retained between the swim bladder and the gut, the pneumatic duct, allowing the fish to fill up the swim bladder by «gulping» air. Excess gas can be removed in a similar manner.

In more derived varieties of fish (the physoclisti) the connection to the digestive tract is lost. In early life stages, these fish must rise to the surface to fill up their swim bladders; in later stages, the pneumatic duct disappears, and the gas gland has to introduce gas (usually oxygen) to the bladder to increase its volume and thus increase buoyancy. This process begins with the acidification of the blood in the rete mirabile when the gas gland excretes lactic acid and produces carbon dioxide, the latter of which acidifies the blood via the bicarbonate buffer system. The resulting acidity causes the hemoglobin of the blood to lose its oxygen (Root effect) which then diffuses partly into the swim bladder. Before returning to the body, the blood re-enters the rete mirabile, and as a result, virtually all the excess carbon dioxide and oxygen produced in the gas gland diffuses back to the arteries supplying the gas gland via a countercurrent multiplication loop. Thus a very high gas pressure of oxygen can be obtained, which can even account for the presence of gas in the swim bladders of deep sea fish like the eel, requiring a pressure of hundreds of bars.[5] Elsewhere, at a similar structure known as the ‘oval window’, the bladder is in contact with blood and the oxygen can diffuse back out again. Together with oxygen, other gases are salted out[clarification needed] in the swim bladder which accounts for the high pressures of other gases as well.[6]

The combination of gases in the bladder varies. In shallow water fish, the ratios closely approximate that of the atmosphere, while deep sea fish tend to have higher percentages of oxygen. For instance, the eel Synaphobranchus has been observed to have 75.1% oxygen, 20.5% nitrogen, 3.1% carbon dioxide, and 0.4% argon in its swim bladder.

Physoclist swim bladders have one important disadvantage: they prohibit fast rising, as the bladder would burst. Physostomes can «burp» out gas, though this complicates the process of re-submergence.

The swim bladder in some species, mainly fresh water fishes (common carp, catfish, bowfin) is interconnected with the inner ear of the fish. They are connected by four bones called the Weberian ossicles from the Weberian apparatus. These bones can carry the vibrations to the saccule and the lagena. They are suited for detecting sound and vibrations due to its low density in comparison to the density of the fish’s body tissues. This increases the ability of sound detection.[7] The swim bladder can radiate the pressure of sound which help increase its sensitivity and expand its hearing. In some deep sea fishes like the Antimora, the swim bladder maybe also connected to the macula of saccule in order for the inner ear to receive a sensation from the sound pressure.[8]

In red-bellied piranha, the swim bladder may play an important role in sound production as a resonator. The sounds created by piranhas are generated through rapid contractions of the sonic muscles and is associated with the swim bladder.[9]

Teleosts are thought to lack a sense of absolute hydrostatic pressure, which could be used to determine absolute depth.[10] However, it has been suggested that teleosts may be able to determine their depth by sensing the rate of change of swim-bladder volume.[11]

Evolution[edit]

The illustration of the swim bladder in fishes … shows us clearly the highly important fact that an organ originally constructed for one purpose, namely, flotation, may be converted into one for a widely different purpose, namely, respiration. The swim bladder has, also, been worked in as an accessory to the auditory organs of certain fishes. All physiologists admit that the swimbladder is homologous, or “ideally similar” in position and structure with the lungs of the higher vertebrate animals: hence there is no reason to doubt that the swim bladder has actually been converted into lungs, or an organ used exclusively for respiration. According to this view it may be inferred that all vertebrate animals with true lungs are descended by ordinary generation from an ancient and unknown prototype, which was furnished with a floating apparatus or swim bladder.

Charles Darwin, 1859[3]

Swim bladders are evolutionarily closely related (i.e., homologous) to lungs. Traditional wisdom[clarification needed] has long held that the first lungs, simple sacs connected to the gut that allowed the organism to gulp air under oxygen-poor conditions, evolved into the lungs of today’s terrestrial vertebrates and some fish (e.g., lungfish, gar, and bichir) and into the swim bladders of the ray-finned fish. In 1997, Farmer proposed that lungs evolved to supply the heart with oxygen. In fish, blood circulates from the gills to the skeletal muscle, and only then to the heart. During intense exercise, the oxygen in the blood gets used by the skeletal muscle before the blood reaches the heart. Primitive lungs gave an advantage by supplying the heart with oxygenated blood via the cardiac shunt. This theory is robustly supported by the fossil record, the ecology of extant air-breathing fishes, and the physiology of extant fishes.[12] In embryonal development, both lung and swim bladder originate as an outpocketing from the gut; in the case of swim bladders, this connection to the gut continues to exist as the pneumatic duct in the more «primitive» ray-finned fish, and is lost in some of the more derived teleost orders. There are no animals which have both lungs and a swim bladder.

The cartilaginous fish (e.g., sharks and rays) split from the other fishes about 420 million years ago, and lack both lungs and swim bladders, suggesting that these structures evolved after that split.[12] Correspondingly, these fish also have both heterocercal and stiff, wing-like pectoral fins which provide the necessary lift needed due to the lack of swim bladders. Teleost fish with swim bladders have neutral buoyancy, and have no need for this lift.[13]

Sonar reflectivity[edit]

The swim bladder of a fish can strongly reflect sound of an appropriate frequency. Strong reflection happens if the frequency is tuned to the volume resonance of the swim bladder. This can be calculated by knowing a number of properties of the fish, notably the volume of the swim bladder, although the well-accepted method for doing so[14] requires correction factors for gas-bearing zooplankton where the radius of the swim bladder is less than about 5 cm.[15] This is important, since sonar scattering is used to estimate the biomass of commercially- and environmentally-important fish species.

Deep scattering layer[edit]

Most mesopelagic fishes are small filter feeders which ascend at night using their swimbladders to feed in the nutrient rich waters of the epipelagic zone. During the day, they return to the dark, cold, oxygen deficient waters of the mesopelagic where they are relatively safe from predators. Lanternfish account for as much as 65 percent of all deep sea fish biomass and are largely responsible for the deep scattering layer of the world’s oceans.

Sonar operators, using the newly developed sonar technology during World War II, were puzzled by what appeared to be a false sea floor 300–500 metres deep at day, and less deep at night. This turned out to be due to millions of marine organisms, most particularly small mesopelagic fish, with swimbladders that reflected the sonar. These organisms migrate up into shallower water at dusk to feed on plankton. The layer is deeper when the moon is out, and can become shallower when clouds obscure the moon.[16]

Most mesopelagic fish make daily vertical migrations, moving at night into the epipelagic zone, often following similar migrations of zooplankton, and returning to the depths for safety during the day.[17][18] These vertical migrations often occur over large vertical distances, and are undertaken with the assistance of a swim bladder. The swim bladder is inflated when the fish wants to move up, and, given the high pressures in the mesoplegic zone, this requires significant energy. As the fish ascends, the pressure in the swimbladder must adjust to prevent it from bursting. When the fish wants to return to the depths, the swimbladder is deflated.[19] Some mesopelagic fishes make daily migrations through the thermocline, where the temperature changes between 10 and 20 °C, thus displaying considerable tolerance for temperature change.

Sampling via deep trawling indicates that lanternfish account for as much as 65% of all deep sea fish biomass.[20] Indeed, lanternfish are among the most widely distributed, populous, and diverse of all vertebrates, playing an important ecological role as prey for larger organisms. The estimated global biomass of lanternfish is 550–660 million tonnes, several times the annual world fisheries catch. Lanternfish also account for much of the biomass responsible for the deep scattering layer of the world’s oceans. Sonar reflects off the millions of lanternfish swim bladders, giving the appearance of a false bottom.[21]

Human uses[edit]

In some Asian cultures, the swim bladders of certain large fishes are considered a food delicacy. In China they are known as fish maw, 花膠/鱼鳔,[22] and are served in soups or stews.

The vanity price of a vanishing kind of maw is behind the imminent extinction of the vaquita, the world’s smallest dolphin species. Found only in Mexico’s Gulf of California, the once numerous vaquita are now critically endangered.[23] Vaquita die in gillnets[24] set to catch totoaba (the world’s largest drum fish). Totoaba are being hunted to extinction for its maw, which can sell for as much $10,000 per kilogram.

Swim bladders are also used in the food industry as a source of collagen. They can be made into a strong, water-resistant glue, or used to make isinglass for the clarification of beer.[25] In earlier times they were used to make condoms.[26]

Swim bladder disease[edit]

Swim bladder disease is a common ailment in aquarium fish. A fish with swim bladder disorder can float nose down tail up, or can float to the top or sink to the bottom of the aquarium.[27]

Risk of injury[edit]

Many anthropogenic activities like pile driving or even seismic waves can create high-intensity sound waves that cause a certain amount of damage to fish that possess a gas bladder. Physostomes can release air in order to decrease the tension in the gas bladder that may cause internal injuries to other vital organs, while physoclisti can’t expel air fast enough, making it more difficult to avoid any major injuries.[28] Some of the commonly seen injuries included ruptured gas bladder and renal Haemorrhage. These mostly affect the overall health of the fish and didn’t affect their mortality rate.[28] Investigators used the High-Intensity-Controlled Impedance Fluid Filled (HICI-FT), a stainless-steel wave tube with an electromagnetic shaker. It simulates high-energy sound waves in aquatic far-field, plane-wave acoustic conditions.[29][30]

Similar structures in other organisms[edit]

Siphonophores have a special swim bladder that allows the jellyfish-like colonies to float along the surface of the water while their tentacles trail below. This organ is unrelated to the one in fish.[31]

Gallery[edit]

-

Swim bladder display in a Malacca shopping mall

-

Fish maw soup

References[edit]

- ^ «More on Morphology». www.ucmp.berkeley.edu.

- ^ «Fish». Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia Deluxe 1999. Microsoft. 1999.

- ^ a b Darwin, Charles (1859) Origin of Species Page 190, reprinted 1872 by D. Appleton.

- ^ Nursall, J. R. (1989). «Buoyancy is provided by lipids of larval redlip blennies, Ophioblennius atlanticus». Copeia. 1989 (3): 614–621. doi:10.2307/1445488. JSTOR 1445488.

- ^ Pelster B (December 2001). «The generation of hyperbaric oxygen tensions in fish». News Physiol. Sci. 16 (6): 287–91. doi:10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.6.287. PMID 11719607. S2CID 11198182.

- ^ «Secretion Of Nitrogen Into The Swimbladder Of Fish. Ii. Molecular Mechanism. Secretion Of Noble Gases». Biolbull.org. 1981-12-01. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ^ Kardong, Kenneth (2011-02-16). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 701. ISBN 9780073524238.

- ^ Deng, Xiaohong; Wagner, Hans-Joachim; Popper, Arthur N. (2011-01-01). «The inner ear and its coupling to the swim bladder in the deep-sea fish Antimora rostrata (Teleostei: Moridae)». Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 58 (1): 27–37. Bibcode:2011DSRI…58…27D. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2010.11.001. PMC 3082141. PMID 21532967.

- ^ Onuki, A; Ohmori Y.; Somiya H. (January 2006). «Spinal Nerve Innervation to the Sonic Muscle and Sonic Motor Nucleus in Red Piranha, Pygocentrus nattereri (Characiformes, Ostariophysi)». Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 67 (2): 11–122. doi:10.1159/000089185. PMID 16254416. S2CID 7395840.

- ^ Bone, Q.; Moore, Richard H. (2008). Biology of fishes (3rd., Thoroughly updated and rev ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415375627.

- ^ Taylor, Graham K.; Holbrook, Robert Iain; de Perera, Theresa Burt (6 September 2010). «Fractional rate of change of swim-bladder volume is reliably related to absolute depth during vertical displacements in teleost fish». Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 7 (50): 1379–1382. doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0522. PMC 2894882. PMID 20190038.

- ^ a b Farmer, Colleen (1997). «Did lungs and the intracardiac shunt evolve to oxygenate the heart in vertebrates» (PDF). Paleobiology. 23 (3): 358–372. doi:10.1017/S0094837300019734. S2CID 87285937.

- ^ Kardong, KV (1998) Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution2nd edition, illustrated, revised. Published by WCB/McGraw-Hill, p. 12 ISBN 0-697-28654-1

- ^ Love R. H. (1978). «Resonant acoustic scattering by swimbladder-bearing fish». J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 64 (2): 571–580. Bibcode:1978ASAJ…64..571L. doi:10.1121/1.382009.

- ^ Baik K. (2013). «Comment on «Resonant acoustic scattering by swimbladder-bearing fish» [J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 64, 571–580 (1978)] (L)». J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133 (1): 5–8. Bibcode:2013ASAJ..133….5B. doi:10.1121/1.4770261. PMID 23297876.

- ^ Ryan P «Deep-sea creatures: The mesopelagic zone» Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 21 September 2007.

- ^ Moyle, Peter B.; Cech, Joseph J. (2004). Fishes : an introduction to ichthyology (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 585. ISBN 9780131008472.

- ^ Bone, Quentin; Moore, Richard H. (2008). «Chapter 2.3. Marine habitats. Mesopelagic fishes». Biology of fishes (3rd ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 38. ISBN 9780203885222.

- ^ Douglas, EL; Friedl, WA; Pickwell, GV (1976). «Fishes in oxygen-minimum zones: blood oxygenation characteristics». Science. 191 (4230): 957–959. Bibcode:1976Sci…191..957D. doi:10.1126/science.1251208. PMID 1251208.

- ^ Hulley, P. Alexander (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ^ R. Cornejo; R. Koppelmann & T. Sutton. «Deep-sea fish diversity and ecology in the benthic boundary layer».

- ^ Teresa M. (2009) A Tradition of Soup: Flavors from China’s Pearl River Delta Page 70, North Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781556437656.

- ^ Rojas-Bracho, L. & Taylor, B.L. (2017). «Vaquita (Phocoena sinus)». IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T17028A214541137.en. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ «‘Extinction Is Imminent’: New report from Vaquita Recovery Team (CIRVA) is released». IUCN SSC — Cetacean Specialist Group. 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- ^ Bridge, T. W. (1905) [1] «The Natural History of Isinglass»

- ^ Huxley, Julian (1957). «Material of early contraceptive sheaths». British Medical Journal. 1 (5018): 581–582. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5018.581-b. PMC 1974678.

- ^ Johnson, Erik L. and Richard E. Hess (2006) Fancy Goldfish: A Complete Guide to Care and Collecting, Weatherhill, Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-8348-0448-4

- ^ a b Halvorsen, Michele B.; Casper, Brandon M.; Matthews, Frazer; Carlson, Thomas J.; Popper, Arthur N. (2012-12-07). «Effects of exposure to pile-driving sounds on the lake sturgeon, Nile tilapia and hogchoker». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1748): 4705–4714. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1544. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3497083. PMID 23055066.

- ^ Halvorsen, Michele B.; Casper, Brandon M.; Woodley, Christa M.; Carlson, Thomas J.; Popper, Arthur N. (2012-06-20). «Threshold for Onset of Injury in Chinook Salmon from Exposure to Impulsive Pile Driving Sounds». PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e38968. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…738968H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038968. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3380060. PMID 22745695.

- ^ Popper, Arthur N.; Hawkins, Anthony (2012-01-26). The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781441973115.

- ^ Clark, F. E.; C. E. Lane (1961). «Composition of float gases of Physalia physalis». Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 107 (3): 673–674. doi:10.3181/00379727-107-26724. PMID 13693830. S2CID 2687386.

Further references[edit]

- Bond, Carl E. (1996) Biology of Fishes, 2nd ed., Saunders, pp. 283–290.

- Pelster, Bernd (1997) «Buoyancy at depth» In: WS Hoar, DJ Randall and AP Farrell (Eds) Deep-Sea Fishes, pages 195–237, Academic Press. ISBN 9780080585406.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Air bladder» redirects here. For the special effects technique, see Air bladder effect.

This article is about the organ found in many fish species. For the mathematical shape, see Fish bladder.

The swim bladder of a rudd

Internal positioning of the swim bladder of a bleak

S: anterior, S’: posterior portion of the air bladder

œ: œsophagus; l: air passage of the air bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish[1]) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their current water depth without having to expend energy in swimming.[2] Also, the dorsal position of the swim bladder means the center of mass is below the center of volume, allowing it to act as a stabilizing agent. Additionally, the swim bladder functions as a resonating chamber, to produce or receive sound.

The swim bladder is evolutionarily homologous to the lungs. Charles Darwin remarked upon this in On the Origin of Species.[3] Darwin reasoned that the lung in air-breathing vertebrates had derived from a more primitive swim bladder.

In the embryonic stages, some species, such as redlip blenny,[4] have lost the swim bladder again, mostly bottom dwellers like the weather fish. Other fish—like the opah and the pomfret—use their pectoral fins to swim and balance the weight of the head to keep a horizontal position. The normally bottom dwelling sea robin can use their pectoral fins to produce lift while swimming.

The gas/tissue interface at the swim bladder produces a strong reflection of sound, which is used in sonar equipment to find fish.

Cartilaginous fish, such as sharks and rays, do not have swim bladders. Some of them can control their depth only by swimming (using dynamic lift); others store fats or oils with density less than that of seawater to produce a neutral or near neutral buoyancy, which does not change with depth.

Structure and function[edit]

Swim bladder from a bony (teleost) fish

The swim bladder normally consists of two gas-filled sacs located in the dorsal portion of the fish, although in a few primitive species, there is only a single sac. It has flexible walls that contract or expand according to the ambient pressure. The walls of the bladder contain very few blood vessels and are lined with guanine crystals, which make them impermeable to gases. By adjusting the gas pressurising organ using the gas gland or oval window, the fish can obtain neutral buoyancy and ascend and descend to a large range of depths. Due to the dorsal position it gives the fish lateral stability.

In physostomous swim bladders, a connection is retained between the swim bladder and the gut, the pneumatic duct, allowing the fish to fill up the swim bladder by «gulping» air. Excess gas can be removed in a similar manner.

In more derived varieties of fish (the physoclisti) the connection to the digestive tract is lost. In early life stages, these fish must rise to the surface to fill up their swim bladders; in later stages, the pneumatic duct disappears, and the gas gland has to introduce gas (usually oxygen) to the bladder to increase its volume and thus increase buoyancy. This process begins with the acidification of the blood in the rete mirabile when the gas gland excretes lactic acid and produces carbon dioxide, the latter of which acidifies the blood via the bicarbonate buffer system. The resulting acidity causes the hemoglobin of the blood to lose its oxygen (Root effect) which then diffuses partly into the swim bladder. Before returning to the body, the blood re-enters the rete mirabile, and as a result, virtually all the excess carbon dioxide and oxygen produced in the gas gland diffuses back to the arteries supplying the gas gland via a countercurrent multiplication loop. Thus a very high gas pressure of oxygen can be obtained, which can even account for the presence of gas in the swim bladders of deep sea fish like the eel, requiring a pressure of hundreds of bars.[5] Elsewhere, at a similar structure known as the ‘oval window’, the bladder is in contact with blood and the oxygen can diffuse back out again. Together with oxygen, other gases are salted out[clarification needed] in the swim bladder which accounts for the high pressures of other gases as well.[6]

The combination of gases in the bladder varies. In shallow water fish, the ratios closely approximate that of the atmosphere, while deep sea fish tend to have higher percentages of oxygen. For instance, the eel Synaphobranchus has been observed to have 75.1% oxygen, 20.5% nitrogen, 3.1% carbon dioxide, and 0.4% argon in its swim bladder.

Physoclist swim bladders have one important disadvantage: they prohibit fast rising, as the bladder would burst. Physostomes can «burp» out gas, though this complicates the process of re-submergence.

The swim bladder in some species, mainly fresh water fishes (common carp, catfish, bowfin) is interconnected with the inner ear of the fish. They are connected by four bones called the Weberian ossicles from the Weberian apparatus. These bones can carry the vibrations to the saccule and the lagena. They are suited for detecting sound and vibrations due to its low density in comparison to the density of the fish’s body tissues. This increases the ability of sound detection.[7] The swim bladder can radiate the pressure of sound which help increase its sensitivity and expand its hearing. In some deep sea fishes like the Antimora, the swim bladder maybe also connected to the macula of saccule in order for the inner ear to receive a sensation from the sound pressure.[8]

In red-bellied piranha, the swim bladder may play an important role in sound production as a resonator. The sounds created by piranhas are generated through rapid contractions of the sonic muscles and is associated with the swim bladder.[9]

Teleosts are thought to lack a sense of absolute hydrostatic pressure, which could be used to determine absolute depth.[10] However, it has been suggested that teleosts may be able to determine their depth by sensing the rate of change of swim-bladder volume.[11]

Evolution[edit]

The illustration of the swim bladder in fishes … shows us clearly the highly important fact that an organ originally constructed for one purpose, namely, flotation, may be converted into one for a widely different purpose, namely, respiration. The swim bladder has, also, been worked in as an accessory to the auditory organs of certain fishes. All physiologists admit that the swimbladder is homologous, or “ideally similar” in position and structure with the lungs of the higher vertebrate animals: hence there is no reason to doubt that the swim bladder has actually been converted into lungs, or an organ used exclusively for respiration. According to this view it may be inferred that all vertebrate animals with true lungs are descended by ordinary generation from an ancient and unknown prototype, which was furnished with a floating apparatus or swim bladder.

Charles Darwin, 1859[3]

Swim bladders are evolutionarily closely related (i.e., homologous) to lungs. Traditional wisdom[clarification needed] has long held that the first lungs, simple sacs connected to the gut that allowed the organism to gulp air under oxygen-poor conditions, evolved into the lungs of today’s terrestrial vertebrates and some fish (e.g., lungfish, gar, and bichir) and into the swim bladders of the ray-finned fish. In 1997, Farmer proposed that lungs evolved to supply the heart with oxygen. In fish, blood circulates from the gills to the skeletal muscle, and only then to the heart. During intense exercise, the oxygen in the blood gets used by the skeletal muscle before the blood reaches the heart. Primitive lungs gave an advantage by supplying the heart with oxygenated blood via the cardiac shunt. This theory is robustly supported by the fossil record, the ecology of extant air-breathing fishes, and the physiology of extant fishes.[12] In embryonal development, both lung and swim bladder originate as an outpocketing from the gut; in the case of swim bladders, this connection to the gut continues to exist as the pneumatic duct in the more «primitive» ray-finned fish, and is lost in some of the more derived teleost orders. There are no animals which have both lungs and a swim bladder.

The cartilaginous fish (e.g., sharks and rays) split from the other fishes about 420 million years ago, and lack both lungs and swim bladders, suggesting that these structures evolved after that split.[12] Correspondingly, these fish also have both heterocercal and stiff, wing-like pectoral fins which provide the necessary lift needed due to the lack of swim bladders. Teleost fish with swim bladders have neutral buoyancy, and have no need for this lift.[13]

Sonar reflectivity[edit]

The swim bladder of a fish can strongly reflect sound of an appropriate frequency. Strong reflection happens if the frequency is tuned to the volume resonance of the swim bladder. This can be calculated by knowing a number of properties of the fish, notably the volume of the swim bladder, although the well-accepted method for doing so[14] requires correction factors for gas-bearing zooplankton where the radius of the swim bladder is less than about 5 cm.[15] This is important, since sonar scattering is used to estimate the biomass of commercially- and environmentally-important fish species.

Deep scattering layer[edit]

Most mesopelagic fishes are small filter feeders which ascend at night using their swimbladders to feed in the nutrient rich waters of the epipelagic zone. During the day, they return to the dark, cold, oxygen deficient waters of the mesopelagic where they are relatively safe from predators. Lanternfish account for as much as 65 percent of all deep sea fish biomass and are largely responsible for the deep scattering layer of the world’s oceans.

Sonar operators, using the newly developed sonar technology during World War II, were puzzled by what appeared to be a false sea floor 300–500 metres deep at day, and less deep at night. This turned out to be due to millions of marine organisms, most particularly small mesopelagic fish, with swimbladders that reflected the sonar. These organisms migrate up into shallower water at dusk to feed on plankton. The layer is deeper when the moon is out, and can become shallower when clouds obscure the moon.[16]

Most mesopelagic fish make daily vertical migrations, moving at night into the epipelagic zone, often following similar migrations of zooplankton, and returning to the depths for safety during the day.[17][18] These vertical migrations often occur over large vertical distances, and are undertaken with the assistance of a swim bladder. The swim bladder is inflated when the fish wants to move up, and, given the high pressures in the mesoplegic zone, this requires significant energy. As the fish ascends, the pressure in the swimbladder must adjust to prevent it from bursting. When the fish wants to return to the depths, the swimbladder is deflated.[19] Some mesopelagic fishes make daily migrations through the thermocline, where the temperature changes between 10 and 20 °C, thus displaying considerable tolerance for temperature change.

Sampling via deep trawling indicates that lanternfish account for as much as 65% of all deep sea fish biomass.[20] Indeed, lanternfish are among the most widely distributed, populous, and diverse of all vertebrates, playing an important ecological role as prey for larger organisms. The estimated global biomass of lanternfish is 550–660 million tonnes, several times the annual world fisheries catch. Lanternfish also account for much of the biomass responsible for the deep scattering layer of the world’s oceans. Sonar reflects off the millions of lanternfish swim bladders, giving the appearance of a false bottom.[21]

Human uses[edit]

In some Asian cultures, the swim bladders of certain large fishes are considered a food delicacy. In China they are known as fish maw, 花膠/鱼鳔,[22] and are served in soups or stews.

The vanity price of a vanishing kind of maw is behind the imminent extinction of the vaquita, the world’s smallest dolphin species. Found only in Mexico’s Gulf of California, the once numerous vaquita are now critically endangered.[23] Vaquita die in gillnets[24] set to catch totoaba (the world’s largest drum fish). Totoaba are being hunted to extinction for its maw, which can sell for as much $10,000 per kilogram.

Swim bladders are also used in the food industry as a source of collagen. They can be made into a strong, water-resistant glue, or used to make isinglass for the clarification of beer.[25] In earlier times they were used to make condoms.[26]

Swim bladder disease[edit]

Swim bladder disease is a common ailment in aquarium fish. A fish with swim bladder disorder can float nose down tail up, or can float to the top or sink to the bottom of the aquarium.[27]

Risk of injury[edit]

Many anthropogenic activities like pile driving or even seismic waves can create high-intensity sound waves that cause a certain amount of damage to fish that possess a gas bladder. Physostomes can release air in order to decrease the tension in the gas bladder that may cause internal injuries to other vital organs, while physoclisti can’t expel air fast enough, making it more difficult to avoid any major injuries.[28] Some of the commonly seen injuries included ruptured gas bladder and renal Haemorrhage. These mostly affect the overall health of the fish and didn’t affect their mortality rate.[28] Investigators used the High-Intensity-Controlled Impedance Fluid Filled (HICI-FT), a stainless-steel wave tube with an electromagnetic shaker. It simulates high-energy sound waves in aquatic far-field, plane-wave acoustic conditions.[29][30]

Similar structures in other organisms[edit]

Siphonophores have a special swim bladder that allows the jellyfish-like colonies to float along the surface of the water while their tentacles trail below. This organ is unrelated to the one in fish.[31]

Gallery[edit]

-

Swim bladder display in a Malacca shopping mall

-

Fish maw soup

References[edit]

- ^ «More on Morphology». www.ucmp.berkeley.edu.

- ^ «Fish». Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia Deluxe 1999. Microsoft. 1999.

- ^ a b Darwin, Charles (1859) Origin of Species Page 190, reprinted 1872 by D. Appleton.

- ^ Nursall, J. R. (1989). «Buoyancy is provided by lipids of larval redlip blennies, Ophioblennius atlanticus». Copeia. 1989 (3): 614–621. doi:10.2307/1445488. JSTOR 1445488.

- ^ Pelster B (December 2001). «The generation of hyperbaric oxygen tensions in fish». News Physiol. Sci. 16 (6): 287–91. doi:10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.6.287. PMID 11719607. S2CID 11198182.

- ^ «Secretion Of Nitrogen Into The Swimbladder Of Fish. Ii. Molecular Mechanism. Secretion Of Noble Gases». Biolbull.org. 1981-12-01. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ^ Kardong, Kenneth (2011-02-16). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 701. ISBN 9780073524238.

- ^ Deng, Xiaohong; Wagner, Hans-Joachim; Popper, Arthur N. (2011-01-01). «The inner ear and its coupling to the swim bladder in the deep-sea fish Antimora rostrata (Teleostei: Moridae)». Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 58 (1): 27–37. Bibcode:2011DSRI…58…27D. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2010.11.001. PMC 3082141. PMID 21532967.

- ^ Onuki, A; Ohmori Y.; Somiya H. (January 2006). «Spinal Nerve Innervation to the Sonic Muscle and Sonic Motor Nucleus in Red Piranha, Pygocentrus nattereri (Characiformes, Ostariophysi)». Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 67 (2): 11–122. doi:10.1159/000089185. PMID 16254416. S2CID 7395840.

- ^ Bone, Q.; Moore, Richard H. (2008). Biology of fishes (3rd., Thoroughly updated and rev ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415375627.

- ^ Taylor, Graham K.; Holbrook, Robert Iain; de Perera, Theresa Burt (6 September 2010). «Fractional rate of change of swim-bladder volume is reliably related to absolute depth during vertical displacements in teleost fish». Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 7 (50): 1379–1382. doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0522. PMC 2894882. PMID 20190038.

- ^ a b Farmer, Colleen (1997). «Did lungs and the intracardiac shunt evolve to oxygenate the heart in vertebrates» (PDF). Paleobiology. 23 (3): 358–372. doi:10.1017/S0094837300019734. S2CID 87285937.

- ^ Kardong, KV (1998) Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution2nd edition, illustrated, revised. Published by WCB/McGraw-Hill, p. 12 ISBN 0-697-28654-1

- ^ Love R. H. (1978). «Resonant acoustic scattering by swimbladder-bearing fish». J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 64 (2): 571–580. Bibcode:1978ASAJ…64..571L. doi:10.1121/1.382009.

- ^ Baik K. (2013). «Comment on «Resonant acoustic scattering by swimbladder-bearing fish» [J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 64, 571–580 (1978)] (L)». J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133 (1): 5–8. Bibcode:2013ASAJ..133….5B. doi:10.1121/1.4770261. PMID 23297876.

- ^ Ryan P «Deep-sea creatures: The mesopelagic zone» Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 21 September 2007.

- ^ Moyle, Peter B.; Cech, Joseph J. (2004). Fishes : an introduction to ichthyology (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 585. ISBN 9780131008472.

- ^ Bone, Quentin; Moore, Richard H. (2008). «Chapter 2.3. Marine habitats. Mesopelagic fishes». Biology of fishes (3rd ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 38. ISBN 9780203885222.

- ^ Douglas, EL; Friedl, WA; Pickwell, GV (1976). «Fishes in oxygen-minimum zones: blood oxygenation characteristics». Science. 191 (4230): 957–959. Bibcode:1976Sci…191..957D. doi:10.1126/science.1251208. PMID 1251208.

- ^ Hulley, P. Alexander (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ^ R. Cornejo; R. Koppelmann & T. Sutton. «Deep-sea fish diversity and ecology in the benthic boundary layer».

- ^ Teresa M. (2009) A Tradition of Soup: Flavors from China’s Pearl River Delta Page 70, North Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781556437656.

- ^ Rojas-Bracho, L. & Taylor, B.L. (2017). «Vaquita (Phocoena sinus)». IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T17028A214541137.en. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ «‘Extinction Is Imminent’: New report from Vaquita Recovery Team (CIRVA) is released». IUCN SSC — Cetacean Specialist Group. 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- ^ Bridge, T. W. (1905) [1] «The Natural History of Isinglass»

- ^ Huxley, Julian (1957). «Material of early contraceptive sheaths». British Medical Journal. 1 (5018): 581–582. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5018.581-b. PMC 1974678.

- ^ Johnson, Erik L. and Richard E. Hess (2006) Fancy Goldfish: A Complete Guide to Care and Collecting, Weatherhill, Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-8348-0448-4

- ^ a b Halvorsen, Michele B.; Casper, Brandon M.; Matthews, Frazer; Carlson, Thomas J.; Popper, Arthur N. (2012-12-07). «Effects of exposure to pile-driving sounds on the lake sturgeon, Nile tilapia and hogchoker». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1748): 4705–4714. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1544. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3497083. PMID 23055066.

- ^ Halvorsen, Michele B.; Casper, Brandon M.; Woodley, Christa M.; Carlson, Thomas J.; Popper, Arthur N. (2012-06-20). «Threshold for Onset of Injury in Chinook Salmon from Exposure to Impulsive Pile Driving Sounds». PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e38968. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…738968H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038968. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3380060. PMID 22745695.

- ^ Popper, Arthur N.; Hawkins, Anthony (2012-01-26). The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781441973115.

- ^ Clark, F. E.; C. E. Lane (1961). «Composition of float gases of Physalia physalis». Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 107 (3): 673–674. doi:10.3181/00379727-107-26724. PMID 13693830. S2CID 2687386.

Further references[edit]

- Bond, Carl E. (1996) Biology of Fishes, 2nd ed., Saunders, pp. 283–290.

- Pelster, Bernd (1997) «Buoyancy at depth» In: WS Hoar, DJ Randall and AP Farrell (Eds) Deep-Sea Fishes, pages 195–237, Academic Press. ISBN 9780080585406.