Образуйте от слова ILLUSTRATE однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Still, after finishing school Vrubel decided to study law. While studying at university, Vrubel practised art only through making __________________ for books.

Mikhail Vrubel

Mikhail Vrubel is a renowned Russian painter who worked in almost all genres of art, including graphics and sculpture. He was born in Omsk to an ordinary family. In his early 25__________________ Vrubel was very weak because of the harsh Siberian climate. 26__________________, his family moved to warmer regions, where Vrubel quickly got better. Mikhail Vrubel showed his 27__________________ talent at the age of 10. That is why his father hired a private 28__________________ so that he could learn the advanced painting techniques. Still, after finishing school Vrubel decided to study law. While studying at university, Vrubel practised art only through making 29__________________ for books. He didn’t finish university and entered the Imperial Academy of Arts and made friends with Serov.

1

Образуйте от слова CHILD однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Mikhail Vrubel

Mikhail Vrubel is a renowned Russian painter who worked in almost all genres of art, including graphics and sculpture. He was born in Omsk to an ordinary family. In his early __________________ Vrubel was very weak because of the harsh Siberian climate.

Источник: ЕГЭ по английскому языку 2022. Досрочная волна

2

Образуйте от слова FORTUNATE однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

__________________, his family moved to warmer regions, where Vrubel quickly got better.

Источник: ЕГЭ по английскому языку 2022. Досрочная волна

3

Образуйте от слова ARTIST однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Mikhail Vrubel showed his __________________ talent at the age of 10.

Источник: ЕГЭ по английскому языку 2022. Досрочная волна

4

Образуйте от слова TEACH однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

That is why his father hired a private __________________ so that he could learn the advanced painting techniques.

Источник: ЕГЭ по английскому языку 2022. Досрочная волна

5

Образуйте от слова USUAL однокоренное слово так, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

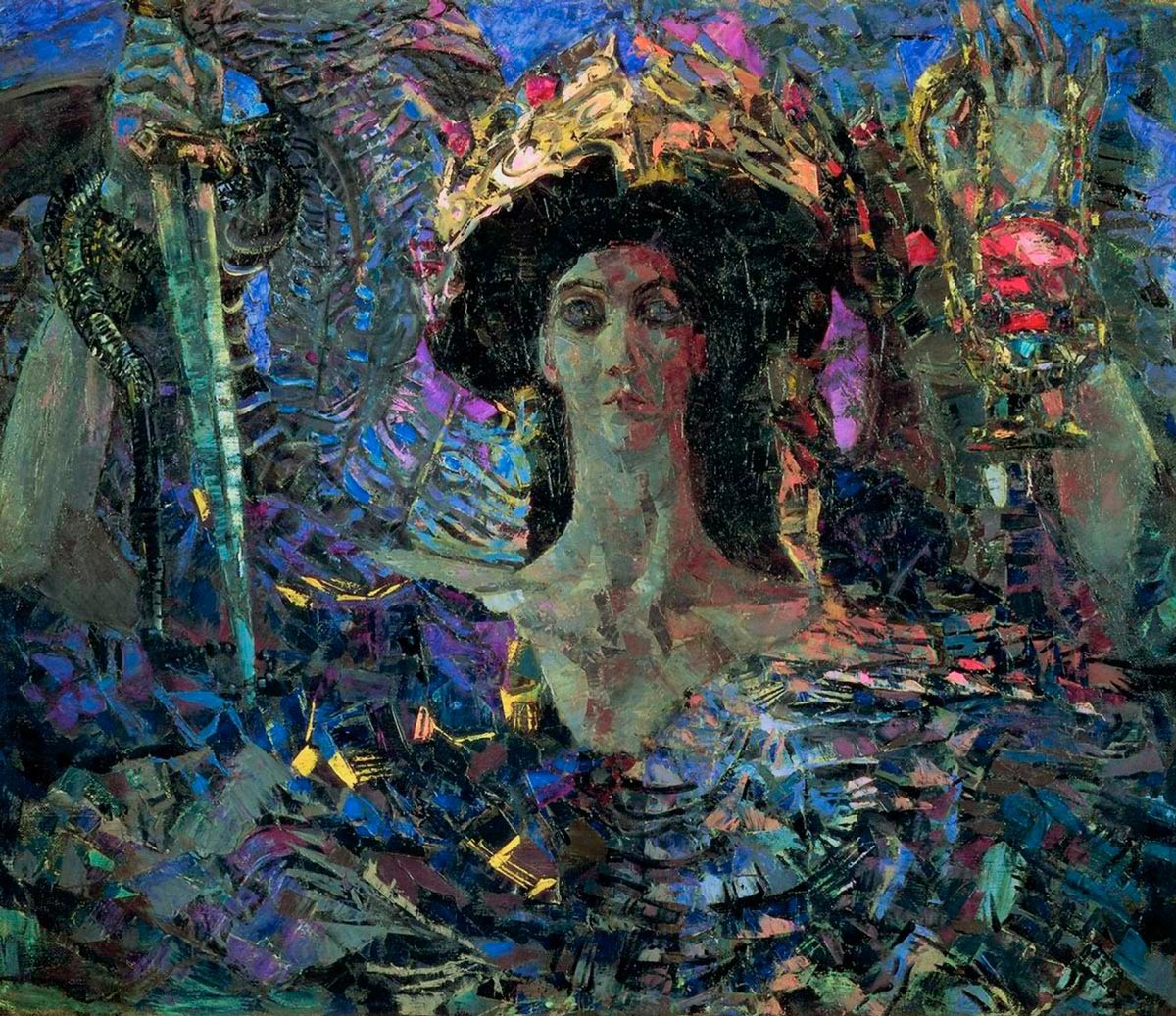

He didn’t finish university and entered the Imperial Academy of Arts and made friends with Serov. His most famous works are the __________________ pictures The Swan Princess and Demon Downcast.

Источник: ЕГЭ по английскому языку 2022. Досрочная волна

Спрятать пояснение

Пояснение.

По структуре предложения и грамматически на месте пропуска должно стоять существительное во множественном числе, которое можно образовать от глагола illustrate с помощью суффикса -ion.

Ответ: illustrations.

Источник: ЕГЭ по английскому языку 2022. Досрочная волна

1) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill was a great political leader and a very clever man. Many British people think since then there ___ (NOT BE) a prime minister better than him.

2) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

He even ___ (WIN) the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953.

3) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

His ___ (FAMOUS) work was a six-volume memoir about WW2, but he wrote some science fiction books as well.

4) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Clouds

Do you like to watch clouds? Many people all over the world enjoy ___ (DO) it.

5) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

There are a lot of different kinds of clouds but they all look white as they reflect the Sun’s light – just like the Moon. It is interesting to know that clouds ___ (NOT BE) unique to our planet.

6) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

In fact, any planet with an atmosphere has ___ (THEY).

7) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически соответствовало содержанию текста.

It takes an hour or ___ (LITTLE) to form a cloud. That is why the weather can change so quickly.

Mikhail Vrubel

Mikhail Vrubel is a renowned Russian painter who worked in almost all genres of art, including graphics and sculpture. He was born in Omsk to an ordinary family. In his early ___ (CHILD) Vrubel was very weak because of the harsh Siberian climate.

9) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

___ (FORTUNATE), his family moved to warmer regions, where Vrubel quickly got better.

10) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Mikhail Vrubel showed his ___ (ARTIST) talent at the age of 10.

11) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

That is why his father hired a private ___ (TEACH) so that he could learn the advanced painting techniques.

12) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

Still, after finishing school Vrubel decided to study law. While studying at university, Vrubel practised art only through making ___ (ILLUSTRATE) for books.

13) Вставьте слово, чтобы оно грамматически и лексически соответствовало содержанию текста.

He didn’t finish university and entered the Imperial Academy of Arts and made friends with Serov. His most famous works are the ___(USUAL) pictures The Swan Princess and Demon Downcast.

|

Mikhail Vrubel |

|

|---|---|

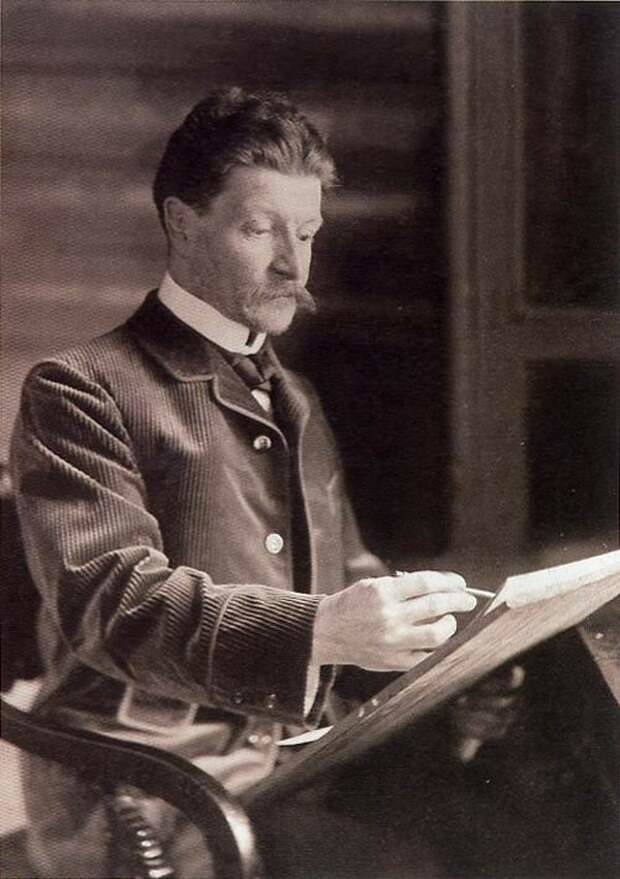

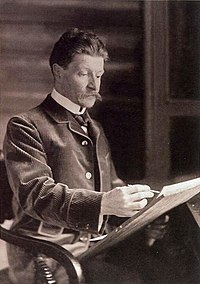

At work, 1900s |

|

| Born |

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Vrubel March 17, 1856 Omsk, Russian Empire |

| Died | April 14, 1910 (age 54)

Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Education | Member Academy of Arts (1905) |

| Alma mater | Imperial Academy of Arts |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, decorative sculpture |

| Notable work | The Demon Seated (1890) The Swan Princess (1900) |

| Movement | Symbolism |

| Patron(s) | Savva Mamontov |

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Vrubel (Russian: Михаил Александрович Врубель; March 17, 1856 – April 14, 1910, all n.s.) was a Russian painter, draughtsman, and sculptor. A prolific and innovative master in various media such as painting, drawing, decorative sculpture, and theatrical art, Vrubel is generally characterized as one of the most important artists in Russian Symbolist tradition and a pioneering figure of Modernist art.

In a 1990 biography of Vrubel, the Soviet art historian Nina Dmitrieva [ru] considered his life and art as a three-act drama with prologue and epilogue, while the transition between acts was rapid and unexpected. The «Prologue» refers to his earlier years of studying and choosing a career path. The «first act» peaked in the 1880s when Vrubel was studying at the Imperial Academy of Arts and then moved to Kiev to study Byzantine and Christian art. The «second act» corresponded to the so-called «Moscow period» that started with The Demon Seated of 1890, followed by Vrubel’s 1896 marriage to the opera singer Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel, his longtime sitter, and ended in 1902 with The Demon Downcast and the subsequent hospitalization of the artist. The «third act» lasted from 1903 to 1906 when Vrubel was suffering from his mental illness that gradually undermined his physical and intellectual capabilities. For the last four years of his life, already being blind, Vrubel lived only physically.[1]

In 1880–1890, Vrubel’s creative aspirations did not find support of the Imperial Academy of Arts and art critics. However, many private collectors and patrons were fascinated with his paintings, including famous maecenas (art patron) Savva Mamontov, as well as painters and critics who coalesced around the journal Mir iskusstva. Eventually, Vrubel’s works were exhibited at Mir Iskusstva’s own art exhibitions and Sergei Diaghilev retrospectives. At the beginning of the 20th century, Vrubel’s art became an organic part of the Russian Art Nouveau. On November 28, 1905, he was awarded the title of Academician of Painting for his «fame in the artistic field» – just when Vrubel almost finished his career as an artist.

Becoming a painter[edit]

Origin. Childhood and adolescence[edit]

The Vrubel family did not belong to the nobility. Great-grandfather of the artist – Anton Antonovich Vrubel (from Polish: wróbel, meaning sparrow) – was originally from Białystok and served as a judge in his local town. His son Mikhail Antonovich Vrubel [ru] (1799–1859) pursued a military career. He retired at the rank of Major General, was twice married and had three sons and four daughters.[2] For the last ten years of his life, Mikhail Antonovich served as an ataman of the Astrakhan Cossacks. At that time, the Astrakhan governor was a famous cartographer and admiral Grigori Basargin [ru]. The governor’s daughter Anna later married the second son of Mikhail Antonovich from the first marriage, Alexander, who previously graduated from the Cadet Corps, served in the Tengin Infantry Regiment, participated in the Caucasian and Crimean Wars. In 1855, their first child Anna Aleksandrovna (1855–1928) was born. Altogether they had four children.[3]

Mikhail Vrubel was born on March 17, 1856. At that time, the Vrubel family lived in Omsk where Alexander was serving as a desk officer of the 2nd Steppe Siberian Corps. Two other children, Alexander and Ekaterina, were also born in Omsk, however, they died before adolescence. Frequent childbirth and adverse Siberian climate significantly weakened Mikhail’s mother’s health and in 1859 she died from consumption. The future painter was only three years old when his mother died. One of the memories that Mikhail had from that period is how his sick mother lay in bed and cut out for her children «little people, horses and different fantastic figures» from paper.[4] Being a weak child from birth, Mikhail started to walk only at the age of three.[5]

The Vrubel family in 1863. From the left – Elizaveta Vessel-Vrubel

Due to constant relocations of their father, Anna and Mikhail spent their childhood moving to the places where Alexander was assigned to serve. In 1859, he was appointed to serve in Astrakhan where he had relatives able to help him with children, but already in 1861 the family had to relocate to Kharkiv. There, little Mikhail quickly learned how to read and developed his interest in book illustrations, especially those from the journal «Zhivopisnoye Obozrenye».[6]

In 1863, Alexander Vrubel got married for the second time to Elizaveta Vessel from Saint Petersburg, who dedicated herself to her husband’s children (her own child was born only in 1867). In 1867, the family moved to Saratov where podpolkovnik Vrubel took command of the provincial garrison. The Vessel family belonged to intelligentsia – a status class of educated people engaged in shaping the culture and politics of their society. Elizaveta’s sister Alexandra Vessel graduated from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and largely contributed to the introducing Mikhail to the world of music. Elizaveta herself spent a lot of time on improving Mikhail’s health; later he even ironically recalled that she made him follow the «diet of raw meat and fish oil». However, there is no doubt that he owed his physical strength to the regime maintained by his stepmother.[7] In addition, Elizaveta’s brother, professional teacher Nicolai Vessel [ru], also participated in children’s education by introducing educational games and home entertainment. Despite the generally good relationships among all the relatives, Anna and Mikhail kept a little aloof from them. Sometimes they behaved coldly to their stepmother calling her with an ironic nickname «Madrin’ka — perl materei». They also explicitly expressed their desire to start an independent life outside home thus making their father upset.[8] By the age of 10, Mikhail expressed artistic talents through drawing, theater and music practicing; that altogether occupied in his future life no less place than painting. According to Dmitrieva, «the boy was like a boy, gifted, but rather promising a versatile amateur than an obsessed artist, whom he later became».[9]

Vrubel with his sister Anna. Gymnasium photo from the 1870s

In addition, Alexander Vrubel hired for Mikhail a private teacher Andrei Godin from the Saratov gymnasium who taught advanced painting techniques. At that time, a copy of «The last Judgement» by Michelangelo was exhibited in Saratov. The painting impressed Mikhail so much, that, according to his sister, he reproduced it from his memory in all details.[10]

Gymnasium[edit]

Mikhail Vrubel started his education at the Fifth St. Petersburg Gymnasium [ru] where the school directorate paid particular attention to the modernization of teaching methods, the advancement of classical studies, the literary development of high school students, dance and gymnastics lessons. His father Alexander was also in Saint Petersburg, voluntarily attending lectures at the Alexander Military Law Academy as an auditor. In addition to his studies at the gymnasium, Mikhail attended painting classes at the school of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. However, he was most interested in natural sciences thanks to his teacher Nicolai Peskov who was a political exile. In 1870, after living three years in Saint Petersburg, the Vrubel family moved to Odessa where Alexander was appointed as a judge in the garrison court.[11]

In Odessa, Mikhail studied at the Richelieu Lyceum. Several letters from him to his sister Anna who was receiving teacher education in Saint Petersburg have been preserved. The first letter dated October 1872; both letters are large and easy to read, with many quotes in French and Latin. In these letters, Mikhail mentioned the paintings that he made – the portrait of his smaller brother Alexander who died in 1869 (reproduced from the photograph), and the portrait of Anna hanging in the father’s office. However, comparing to other interests that Mikhail had, painting classes did not occupy much of his time.[12][13] Vrubel was a quick learner and was the first in his class. He had a special interest in literature, languages, history, and, on vacations, he loved to read to his sister in original Latin. The future painter devoted even his free time to favourite activities. For instance, in one of his letters, he complained to Anna that instead of reading Goethe’s Faust in original and completing 50 exercises in English textbook, he copied in oil «Sunset at Sea» by Ivan Aivazovsky.[9] At the same time, one might say that at that time Mikhail was more interested in theatrical art rather than painting, since he barely mentioned the «Peredvizhniki» exhibition in Odessa but spent several pages describing the Saint Petersburg opera troupe.[14]

University[edit]

The date of Anna Karenina with the son, 1878

After graduating with a distinction, neither Vrubel nor his parents thought of his career as an artist. It was decided to send Mikhail to Saint Petersburg where he could study at the Saint Petersburg State University and live with his uncle Nicolai Vessel, who would also cover Vrubel’s everyday expenses.[14] Mikhail’s decision to study at the Faculty of Law was differently interpreted by Vrubel’s biographers. For example, Alexandre Benois, who studied at the same faculty, suggested that the rationale behind this decision was the family tradition and values that legal profession had among their social circles. In 1876, Vrubel had to repeat the second year due to poor grades and a desire to strengthen his knowledge on the subjects. However, even though Mikhail studied for a year more than was expected, he could not defend his thesis and graduated in the rank of «deistvitel’nyi student [ru]» which was the lowest scientific degree that one can graduate with.[15] Despite deep engagement with philosophy and, particularly, the theory of aesthetics by Immanuel Kant, Mikhail’s s bohemian lifestyle that his uncle allowed him to maintain was partly to blame for not finishing the university. At that time, Vrubel did not spend much time on practicing painting,[16] though he made several illustrations for literary works both classic and contemporary. According to Dmitrieva, «in general… Vrubel’s art is thoroughly «literary»: a rare work of his does not originate in a literary or theatrical source».[17] One of the most famous compositions from that period is «The date of Anna Karenina with the son». According to Domitieva, this was his «pre-Vrubel» stage since the painting mostly reminds of journal illustrations of that time: «utterly romantic, even melodramatic, and very carefully decorated».[18] Active participation in theatrical life (Vrubel personally knew Modest Mussorgsky who frequently visited the Vessel’s house) required considerable expenses which is why Vrubel regularly worked as a tutor and a governess. In 1875, he even travelled to Europe with one of his pupils; together, they visited France, Switzerland and Germany. In addition, Mikhail spent the summer of 1875 at the estate that belonged to a Russian lawyer Dmitrii Berr [ru] (His wife Yulia Berr was a niece of Mikhail Glinka). Then, due to the excellent knowledge of Latin, Vrubel was hired as a tutor at the Papmel family where he guided his former university classmate.[19] According to the memoirs of A. I. Ivanov:

Vrubel lived with the Papmel family as a relative: in the winter he went to the opera with them, in the summer he moved with everyone to their cottage in Peterhof. Papmels put on quite a spread and everything about them was opposite to the way the Vrubel family lived; their house was a full bowl, even in an excessively literal sense, and during his time with Papmels, Vrubel firstly discovered his passion for wine which was never been lacking.[20]

It was the Papmel family prone to aestheticism and bohemian lifestyle that encouraged Vrubel’s dandyism and a desire to paint. In one of his letters from 1879, Vrubel mentioned that he renewed his acquaintance with a Russian watercolourist Emilie Villiers, who in every possible way patronized Mikhail’ pictorial experiences in Odessa. Later, Vrubel began to communicate closely with students of the Imperial Academy of Arts who worked under the patronage of a famous Russian painter Pavel Chistyakov. Vrubel started attending evening academic classes where auditioning was allowed, and started to hone plastic skills.[21] As a result, at the age of 24, Vrubel had a crucial turning point in his life – after graduating from the university and serving a short military service, Vrubel was admitted to the Imperial Academy of Arts.[9]

The 1880s[edit]

The Academy of Arts[edit]

According to Domiteeva, Vrubel’s decision to study at the Academy of Arts came from his engagement with Kant’s theory of aesthetic ideas. His younger colleague and an admirer Stepan Yaremich [ru] suggested that Vrubel adopted Kant’s philosophy that «clarity of the division between physical and moral life» led over time to a separation of these areas in the real life. Mikhail Vrubel demonstrated «softness, pliability, shyness in little things in everyday life; while iron perseverance accompanied his general higher direction of life». However, this was only one side of the story – undoubtedly, at the age of 24, Vrubel considered himself as a genius. According to Kant’s theory of aesthetics, the «genius» category implied working in a sphere «between freedom and nature» that could only be achieved in the field of arts. For a young and gifted Vrubel that inspired his long-term life plan.[22]

Starting from the autumn of 1880, Vrubel audited classes in the Academy and, presumably, started having private lessons at the Chistyakov’s studio. However, these lessons were documented only starting from 1882; the painter himself claimed that he studied with Chistyakov for four years. In his autobiography dated 1901, the painter characterized years spent in the Academy as «the brightest in his artistic career» thanks to Chistyakov. This does not contradict what he wrote to his sister in 1883 (when they renewed mutual correspondence that was broken off for six years):

When I started my lessons with Chistyakov, I passionately followed his main statements because they were nothing less than a formula of my living attitude towards nature, that is embedded in me.[23]

Among Chistyakov’s students there were Ilya Repin, Vasily Surikov, Vasily Polenov, Viktor Vasnetsov, and Valentin Serov all of whom painted in different styles. All of them, including Vrubel, recognized Chistyakov as their only teacher, honouring him to the last days. Due to scepticism prevailing among the second generation of scholars, this type of relationship between the mentor and his students was not quite appreciated. Chistyakov’s method was purely academic, but very «individualistic» since Pavel inspired «sacred concepts» in working on a plastic form, but also taught conscious drawing as well as structural analysis of the form. According to Chistyakov, to construct the painting one needs to break it down to several small planes transmitted by flatnesses, and these planes would form the faces of the volume with its hollows and bulges. Vrubel’s «crystal-like» technique was thus fully mastered by his teacher.[24]

One of the most crucial acquaintances that Vrubel met during his time in the Academy was Valentin Serov. Despite a 10-year age difference, they were connected on different levels, including the deepest one.[25] Throughout the years spent at the Chistyakov’s studio, Vrubel’s motives drastically changed: his dandyism was replaced with asceticism, about which he proudly wrote to his sister.[26] Starting from 1881, after transferring to a life model class, Mikhail visited both Chistyakov’s classes and morning watercolour lessons at the Repin’s studio. However, their relationship with Repin got complicated quickly due to the argument on the painting «Religious Procession in Kursk Governorate». In one of the letters to his sister, Vrubel mentioned that by «taking advantage of the [public] ignorance, Repin stole that special pleasure that distinguishes the state of mind before a work of art from the state of mind before the expanded printed sheet». This quote clearly illustrates Chistyakov’s influence on Vrubel’s philosophy since Pavel was the one who suggested that obedience of techniques to art is the fundamental spiritual property of the Russian creativity.[27]

Model in a Renaissance setting

One of the brightest examples of Vrubel’s academic work is his sketch «Feasting Romans». Even though it formally compiled with rules of academic art, the painting violates all the main canons of academism – the composition does not have the main focus, the plot is unclear.[28]

Judging by the correspondence between Vrubel and his sister, the painter spent almost two years on the painting. The plot was simple: a cupbearer and a young citharode wink to each other sitting nearby the sleeping patrician. The view was quite whimsical – from somewhere on the balcony or a high window. It implied a dim lighting «after sunset, without any reflections of light» for strengthening the silhouette effects. Vrubel’s intention was to make «some similarities with Lawrence Alma-Tadema». The final watercolour sketch grew with sub-stickers and caused Repin’s enthusiasm. However, Vrubel felt intuitively the limit of unsteady forms and eventually abandoned the unfinished paintings refusing to paint a historical picture.[29]

However, Vrubel did not abandon his idea to get paid for his creative work. Thanks to the Papmel family, he received a commission from the industrialist Leopold Koenig [ru]. According to the mutual agreement, the subject and technique of the painting would be left at the discretion of the artist and the fee would be 200 rubles. Mikhail also decided to participate in the contest initiated by the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts and chose the plot of «Hamlet and Ophelia» in the style of Rafael’s realism. The self-portrait sketches of Hamlet and watercolors for the general composition which depict the Danish prince as represented by Vrubel have been preserved. However, the work on the painting was complicated with the worsening relationship between the painter and his father.[30] Having failed with the «Hamlet» as well, Vrubel was persuaded by his friends to depict a real life model. For this role, they chose an experienced model Agafya who was put in the same chair that served as decorations for the «Hamlet», while student Vladimir Derviz [ru] brought some Florentine velvet, Venetian brocade and other things from the Renaissance period from his parents’ house. Vrubel successfully finished the painting «Sitter in the Renaissance Setting» with characteristic for Vrubel «painting embossing» . Under the impression from the «Sitter», Vrubel returned to «Hamlet». This time he painted with oil on a canvas with Serov as a model.[31]

Despite the formal success, Vrubel was not able to graduate from the Academy. However, in 1883, his painting «Betrothal of Mary and Joseph» received the silver medal from the Academy. Following the recommendation of Chistyakov, in the autumn of 1883, professor Adrian Prakhov invited Vrubel to Kiev to work on a restoration of the 12th century St. Cyril’s Monastery. The offer was flattering and promised good earnings therefore the artist agreed to go after the end of the academic year.[32]

Kiev[edit]

The years that Vrubel spent in Kiev turned out to be almost the most important in his career. For the first time in Vrubel’s life, the painter was able to pursue his monumental intentions and return to the fundamentals of the Russian art. In five years, Mikhail completed an enormous number of paintings. For instance, he single-handedly painted murals and icons for the St. Cyril’s church, as well as made 150 drawings for the restoration of the figure of an angel in the dome of the St. Sophia Cathedral. As Dmitrieva noted:

Such a «co-authorship» with the masters of the 12th century was unknown to any of the great artists of the 19th century. The 1880s have just only passed, the first search for national antiquity just started, which no one else besides specialists was interested in, and even those specialists were interested more from the historical point rather than artistic <…> Vrubel in Kiev was the first who bridged archaeological pioneering and restorations to a live contemporary art. At the same time, he did not think of stylization. He felt like an accomplice in the hard work of the ancient masters and tried to be worthy of them.[33]

Prakhov’s invitation was almost coincidental, as he was looking for a qualified painter with some academic training to paint murals in the church, but at the same time not to be recognised enough so he would not require a higher salary.[34] Judging from the correspondence with the family, Vrubel’s contract with Prakhov was for the completion of four icons in the duration of 76 days. The salary indicated was 300 rubles paid in every 24 working days.[35]

«Descent of Holy Spirit on the Apostles»

Vrubel staged his arrival in Kiev in his signature style. Lev Kovalsky, who in 1884 was a student at the Kiev Art School appointed to pick Mikhail up in the station, later recalled:

… Against a background of primitive Kirillovsky hills, a blond, almost white, young man with a particular head and small, almost white, moustaches, stood behind my back. He was of a moderate height, very proportionate, wearing… it stroke me the most…black velvet costume with stockings, short trousers and anklets. <…> In general, he was impersonating a young Venetian from the paintings of Tintoretto or Titian; however, I found out about it only many years later when I visited Venice.[36]

Woman’s Head (Emily Prakhova)

The fresco «Descent of Holy Spirit on the Apostles» that Vrubel painted on the choir of the St. Cyril’s church bridged both features of Byzantine art and his own portrait pursuits. The fresco reflected most of the Vrubel’s characteristic features and depicted twelve Apostles that are situated in a semicircle at the box vault of the choirs. The standing figure of Mary is located in the center of the composition. The background is coloured in blue while the golden rays are coming up to the apostles from the circle featuring the Holy Spirit.[33] The model for Mary’s figure was a paramedic M. Ershova – a frequent guest in the Prakhov’s house and the future wife of one of the painters participating in the restoration process. To Mary’s left stands the apostle that was painted from protoiereus Petr (Lebedintsev) who at that time taught at the Richelieu lyceum. To Mary’s right stands the second apostle for whom the Kiev archaeologist Viktor Goshkevich [ru] was modelling. The third from the right was the head of the Kirillovsky parish Peter Orlovsky who originally discovered the remains of old paintings and interested the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society in their reconstruction. The fourth apostle, with his hands folded in prayer, was Prakhov. Besides the «Descent», Vrubel painted «The entry into Jerusalem» and «The Angels’Lamentation».[37] The «Descent» was painted directly on the wall, without any cardboard and even any preliminary sketches – only certain details were previously specified on small sheets of paper. Remarkably, the painting depicts Apostles in a semicircle with their limbs connecting to the Holy Spirit emblem. This painting style was of Byzantine origin and was inspired by a hammered winged altarpiece from one of the Tiflis monasteries.[38]

The first trip to Italy[edit]

Icon of the Prophet Moses

Vrubel travelled to Venice together with Samuel Gaiduk who was a young artist painting in accordance with Mikhail’s sketches. Their trip had been not without some «adventures», however. According to Prakhov, Vrubel met his friend from St. Petersburg with whom they went out partying during the transfer in Vienna. Gaiduk, who successfully reached Venice, waited two days for Vrubel to arrive. Life in Venice in winter was cheap, and painters shared a studio in the city centre on Via San Maurizio. They both were interested in churches on the abandoned island Torcello.[39]

Dmitrieva described Vrubel’s artistic evolution as following: «Neither Titian and Paolo Veronese, nor magnificent hedonistic atmosphere of the Venetian Cinquecento attracted him. The range of his Venetian addictions is clearly defined: from medieval mosaics and stained glass of the St Mark’s Basilica and Torcello Cathedral to painters of the early Renaissance Vittore Carpaccio, Cima da Conegliano (the figures of which Vrubel found especially noble), Giovanni Bellini. <…> If the first meeting with Byzantine-Russian art in Kiev enriched Vrubel’s envisioning of plastic forms, then Venice enriched his palette and awakened his gift as a colourist.[40]»

These features can be clearly observed in all the three icons that Vrubel painted in Venice for the St. Cyril’s Church – «Saint Kirill», «Saint Afanasii», and gloomy-coloured «Christ the Savior». Being accustomed to intensive work at the Chistyakov’s studio, Vrubel painted all four icons in a month and a half and felt a crave for activities and the lack of communication. In Venice, he accidentally met Dmitri Mendeleev who was married to one of the Chistyakov’ students. Together they discussed how to preserve paintings in the condition of high humidity as well as argued on the advantages of writing in oil on zinc boards before painting on a canvas. The zinc boards for Vrubel’ icons were delivered directly from Kiev; however, for a long time painter could not establish his own techniques and the paint could not stick to the metal. In April, Vrubel only wanted to come back to Russia.[41]

Kiev and Odessa[edit]

Angel with censer and candle. Fresco sketch for the Vladimir Cathedral, 1887

After returning from Venice in 1885, Vrubel spent May and part of June in Kiev. There were rumours that immediately after he came back, he proposed to Emily Prakhova despite her being a married woman. According to one version of the story, Vrubel proclaimed his decision not to Emily but to her husband Adrian Prakhov. Even though Mikhail Vrubel was not denied access to the house, Prakhov was definitely «afraid of him» while Emily resented his immaturity.[42] Apparently, the incident described a year later by Vrubel’s friend Konstantin Korovin belongs to this period:

It was a hot summer. We went swimming at the big lake in the garden. <…> «What are these big white strips at your chest that look like scars?» –» Yes, these are scars. I cut myself with a knife.» <…> «… But still tell me, Mikhail Alexandrovich, why did you cut yourself – it must be painful. What is this – like a surgery?» I looked closer – yes, these were large white scars, lots of them. «Will you understand – said Mikhail Alexandrovich – It means that I loved a woman, she did not love me – maybe loved me, but much interfered with her understanding of me. I suffered from the inability to explain this to her. I suffered, but when I cut myself, the suffering decreased.[43]

At the end of June 1885, Vrubel traveled to Odessa where he renewed his acquaintance with the Russian sculptor Boris Edwards [ru] with whom he previously attended classes at the Art school. Edwards, together with Kyriak Kostandi, tried to reform the Odessa Art School and decided to elicit Vrubel’s help. He settled Vrubel in his own house and tried to persuade him to stay in Odessa forever.[44] In summer, Serov arrived in Odessa and Vrubel for the first time told him about his plan to paint the «Demon». In letters to his family, Vrubel also mentioned a tetralogy that probably became one of his side interests. In 1886 Vrobel went to Kiev to celebrate the new year using the money that his father sent him for a trip home (at that time the family resided in Kharkiv).[45]

In Kiev, Vrubel met frequently with associates of writer Ieronim Yasinsky. He also met Korovin for the first time. Despite the intensive work, the painter led a «bohemian» lifestyle and became a regular in the café-chantant «Shato-de-fler». This depleted his meager salary and the main source of income became the sugar manufacturer Ivan Tereshchenko who immediately gave the painter 300 rubles toward the expenses of his planned «Oriental Tale». Vrubel used to throw his money in the café-сhantant.[46]

Tombstone Crying, the second version. Akvarel, 1887. Stored at the Kyiv Art Gallery

At the same time, Adrian Prakhov organized painting of the St Volodymyr’s Cathedral and, without regard to his personal attitudes, invited Vrubel. Despite Vrubel’s carelessness towards his works inspired by his «bohemian» lifestyle, he created no less than six versions of the «Tombstone Crying» (only four of them have been preserved). The story is not included in the Gospel and not usual for the Russian Orthodox art, but can be seen in some icons from the Italian Renaissance. Though he clearly understood their significance and originality, Prakhov rejected Vrubel’s independent paintings since they differed significantly from the works of other participating colleagues and would have unbalanced the relative integrity of the already-assembled murals.[47] Prakhov once noted that the a new cathedral «in a very special style» would need to be built to accommodate Vrubel’ paintings.[48]

In addition to commissioned works, Vrubel attempted to paint «Praying for the cup» just «for himself». However, he experienced a severe mental crisis while trying to finish it. He wrote to his sister:

I draw and paint Christ with all my might, but, at the same time, presumably, because I am far away from my family, all religious rituals, including Resurrection of Jesus look so alien, that I am even annoyed with it.[49]

Portrait of a Girl against a Persian Carpet, 1886. Stored at the Kyiv Art Gallery

While painting murals in the Kiev churches, Vrubel simultaneously was drawn to the image of the Demon. According to P. Klimov, it was quite logical and even natural for Vrubel to transfer techniques acquired during the painting of sacred images to completely opposite images, and it illustrates the direction of his pursuits.[50] His father Alexander visited him in Kiev when Mikhail had some intense mental struggles. Alexander Vrubel was terrified with Mikhail’s lifestyle: «no warm blanket, no warm coat, no cloth except the one that is on him… Painfully, bitterly to tears”.[51] The father also saw the first version of the «Demon» that disgusted him. He even noted that this painting would be unlikely to connect with either the public or with representatives of the Academy of art. As a result, Mikhail destroyed the painting, and many other works that he created in Kiev.[52] To earn a living, the painter started to paint the already promised «Oriental Tail», but could only finish a watercolour. He tried to give it to Emily Prakhova as a gift; and tore it up after she rejected it. But then he reconsidered and glued together the pieces of the destroyed work. The only finished painting from this period was the «Portrait of a Girl against a Persian Carpet» depicting Mani Dakhnovich, the daughter of the loan office owner. Dmitrieva defined the genre of this painting as a «portrait-fantasy». The customer, though, did not like the final version, and the work was later bought by Tereshchenko.[53]

The painter’s mental crisis is clear in the following incident. On a visit to Prakhov, where a group of artists were participating in the painting of the cathedral, Vrubel proclaimed that his father died and so he needed urgently to travel to Kharkiv. The painters raised money for his trip. The next day, Alexander Vrubel came to Prakhov looking for his son. Confused Prakhov had to explain to him that Vrubel’s disappearance was due to his infatuation with an English singer from the café-chantant.[54] Nevertheless, friends tried to ensure that Vrubel had regular income. He was assigned a minor work in the Vladimyr’s Cathedral – to draw ornaments and the «Seven days for an eternity» in one of the plafonds according to the sketches made by brothers Pavel and Alexander Swedomsky [ru]. In addition, Vrubel started to teach at the Kiev Art School. All his income streams were unofficial, without any signed contracts.[55] Summarizing Mikhail’s life in the «Kiev period», Dmitrieva wrote:

He lived on the outskirts of Kiev, getting inspirations only from the ancient masters. He was about to enter the thick of the artistic life – modern life. This happened when he moved to Moscow.[56]

The Moscow period (1890–1902)[edit]

Moving to Moscow[edit]

In 1889, Mikhail Vrubel had to urgently travel to Kazan where his father got seriously ill; later he recovered, but due to illness, still had to resign and then settle down in Kiev. In September, Mikhail went to Moscow to visit some acquaintances and, as a result, decided to stay there for the next 15 years.[57]

Vrubel’s moving to Moscow was accidental, like many other things that happened in his life. Most likely, he travelled there because he fell in love with a circus horsewoman which he met thanks to Yasinsky’s brother who performed under the pseudonym «Alexander Zemgano». As a result, Vrubel settled at the Korovin’s studio on the Dolgorukovskaya street [ru].[58] Vrubel, Korovin and Serov even had an idea to share a studio but, however, it did not translate into reality due to deteriorating relations with Serov. Later, Korovin introduced Vrubel to the famous patron of the arts Savva Mamontov.[59] In December, Vrubel moved to the Mamontov’s house on the Sadovaya-Spasskaya street [ru] ( outbuilding of the town estate of Savva Mamontov). According to Domiteeva, he was invited «not without attention to his skills as a governess».[60] However, relationship between Vrubel and the Mamontov family did not work out – patron’s wife could not stand Vrubel and openly called him «a blasphemer and a drunkard». Soon painter moved to a rental apartment.[61]

The Demon[edit]

Tamara and Demon. Illustration to Lermontov’s poem, 1890

A return to the theme of the Demon coincided with the project initiated by the Kushnerev brothers and the editor Petr Konchalovsky [ru] who aimed to publish the two-volume book dedicated to the jubilee of Mikhail Lermontov with illustrations of «our best artistic forces». Altogether, there were 18 painters, including Ilya Repin, Ivan Shishkin, Ivan Aivazovsky, Leonid Pasternak, Apollinary Vasnetsov. Of these, Vrubel was the only one who was completely unknown to the public.[62] It is not known who drew the publishers’ attention to Vrubel. According to different versions, Vrubel was introduced to Konchalovsky by Mamontov, Korovin and even Pasternak who was responsible for editing.[62] The salary for the work was quite small (800 rubles for 5 big and 13 small illustrations).[63] Due to their complexity, his paintings were hard to reproduce and Vrubel had to amend them. The main difficulty, however, was that his colleagues did not understand Vrubel’s art. In spite of this, the illustrated publication was approved by the censorship authorities on April 10, 1891. Immediately thereafter the publication was widely discussed in the press who harshly criticized illustrations for their «rudeness, ugliness, caricature, and absurdity».[64] Even people who were well-disposed to Vrubel did not understand him. So the painter changed his views on aesthetics suggesting that the «true art» is incomprehensible to almost anyone, and «comprehensibility» was as suspicious for him as «incomprehensibility» was for others.[65]

Vrubel made all his illustrations in black watercolour; monochromaticity made it possible to emphasize the dramatic nature of the subject and made it possible to show the range of textured pursuits explored by the artist. The Demon was an archetypal «fallen angel» who simultaneously bridged men and female figures. Tamara was differently depicted on every image, and that emphasized her unavoidable choice between earthly and heavenly.[66] According to Dmitrieva, Vrubel’s illustrations show the painter to be at the peak of his ability as a graphic artist.[67]

While working on the illustrations, Vrubel painted his first large painting on the same topic – «The Demon Seated». This painting is a representation of the Demon at the beginning of Lermontov’s poem and the emptiness and despair he then feels.[68] According to Klimov, it was both the most famous of the Vrubel’s Demons and the freest from any literary associations.[66] On May 22, 1890, in the letter to his sister, Vrubel mentioned:

… I am painting the Demon, meaning not that fundamental «Demon» that I will create later, but a «demonic» – a half-naked, winged, young sadly thoughtful figure who sits embracing her knees against the sunset and looks at a flowering clearing with which branches stretching under the flowers that stretch to her.[69]

The multi-color picture turned out to be more ascetic than the monochrome illustrations.[70] The colours Vrubel uses have a brittle, crystal-like quality which emphasises the livelesness, sterility and coldness of the Demon reflected in the surrounding nature.[71] In the painting Vrubel has used his typical color palette of blues and purples, which reminds of Byzantine mosaics.[72] One of the characteristics of Vrubel’s art is the glowing sparkling effect many of his paintings possess. This fits within the Byzantine tradition where such glowy and shiny effects of the mosaics were meant to express God’s miraculous incarnation.[73] Vrubel’s goals may not have been to express this particular thing, but it was to give his paintings a spiritual, otherworldly sensation.

The painting’s texture and colour emphasize the melancholic character of the Demon’s nature that yearns for a living world. It is characteristic that the flowers surrounding it are cold crystals that reproduce fractures of rocks. Alienation of the Demon to the world is emphasized by «stone» clouds.[69] The opposition between the Demon’s aliveness and strength and his inability/lack of desire to do something is represented by an emphasis on the Demon’s muscular body and his interlocked fingers. These elements contrast with the helpless sentiments that are conveyed by his slumping body and the sadness in the Demon’s face.[74] The figure may be strong and muscular on the outside, but it is passive and introverted in its posture.[75] The figure of the Demon is not depicted as an incarnation of the Devil, but as a human being that is torn apart by suffering.[76] ‘The Demon’ can be seen as a manifestation of Vrubel’s long search for spiritual freedom. Despite Vrubel’s own description, the Demon does not have wings, but there is their mirage formed by the contour of large inflorescences behind his shoulder and folded hair.[77] The painter returned to his image only in 8 years.[66]

Abramtsevo studios[edit]

On July 20, 1890, the 22-year-old painter A. Mamontov died in the Abramtsevo Colony. As Mamontov’s friend, Mikhail Vrubel attended the funeral. He became so fond of the local landscapes that decided to stay in there. In Abramtsevo, Vrubel became fascinated with ceramics and soon after that he proudly mentioned to his sister Anna that he now heads the «factory of ceramic tiles and terracotta decorations».[78] Savva Mamontov did not understand Vrubel’ aesthetic aspirations but recognized his talent, and was trying his best to create a suitable living environment for the painter. For the first time in his life, Vrubel ceased to depend noble families for his support and started earning good money by completing several ceramic commissions; decorating a majolica chapel on the grave of A. Mamontov; projecting the extension in the «Roman-Byzantine style» to the Mamontov’s mansion.[79] According to Dmitrieva, «Vrubel… seemed to be irreplaceable as he could easily do any art, except writing texts. Sculpture, mosaics, stained glass, maiolica, architectural masks, architectural projects, theatrical scenery, costumes – in all of these he felt inherently comfortable. His decorative and graphic idea poured forth like a broken water main – sirins, rusalkas, sea divas, knights, elves, flowers, dragonflies, etc. were done «stylishly», with an understanding of the characteristics of the material and the surroundings. His goal was to find the «pure and stylishly beautiful,» that at the same time made its way into everyday life, and thereby to the heart of the public. Vrubel became one of the founders of the “Russian Art Nouveau» – the «new style» that added to the neo-Russian romanticism of the Mamontov’s circle, and partially grew out of it.»[80]

Fireplace «Volga Svyatoslavich and Mikula Selyaninovich» in the Dom Bazhanova [ru], 1908

Mamontov’s studio in Abramtsevo and Tenisheva’s studio in Talashkino embodied the principles of the «Arts and Crafts movement,» initially founded by William Morris and his followers. Supporters discussed a revival of Russian traditional crafts at the same time as machine fabrication contradicted the uniqueness which was the main art principle in Art Nouveau.[81] Vrubel worked in both Abramtsevo and Talashkino. However, both of these studies differed in the aspects of art. For instance, Mamontov mostly concentrated on theatrical and architecture projects while Tenisheva focused on Russian national traditions.[82] Abramtsevo Potter’s Factory’s ceramics played a significant role in the revival of maiolica in Russia. Vrubel was attracted to it because of maiolica’s simplicity, spontaneity, and its rough texture and whimsical spills of glaze. Ceramics allowed Vrubel to experiment freely with plastic and artistic possibilities of the material. The lack of craftsmanship with its patterns allowed to put his fantasies into life.[83] In Abramtsevo, Vrubel’ plans were supported and brought to life by the famous ceramist Peter Vaulin.[84]

The return trip to Italy[edit]

In 1891, the Mamontov family went to Italy. They planned travel itineraries around the interests of Abramtsevo pottery studio. Vrubel accompanied the family as a consultant which led to a conflict between him and Mamontov’s wife, Elizaveta. Thus, Mamontov and Vrubel went to Milan where Vrubel’s sister Elizaveta (Liliia) was studying.[85] It was suggested that the painter would spend winter in Rome where he might finish the Mamontov’s order – decorations for «The Merry Wives of Windsor» and design the new curtain for the Private Opera. Savva Mamontov paid Vrubel a monthly salary; however, an attempt to settle him in the Mamontov’s house led to a scandal with Elizaveta after which Vrubel decided to stay with Svedomsky.[86]

Vrubel did not get along with other Russian artists working in Rome and continuously accused them with the lack of artistic talent, plagiarism, and other things. He was much closer to brothers Alexander and Pavel Svedomsky with whom he regularly visited variete[clarification needed] «Apollon» and café «Aran’o». He also enjoyed their studio which was rebuilt from the former greenhouse. It had glass walls and the Roman ceiling which made it very hard to stay there in winter due to cold. Svedomskys unconditionally recognized Vrubel’s creative superiority and not only settled him at their house but also shared commercial orders with him.[87] In the end, Mamontov arranged Vrubel’s stay at the studio of half Italian Alexander Rizzoni who graduated from the Russian Academy of Arts. Vrubel highly respected him and willingly worked under the Rizzoni’s supervision. The main reason for this was that Rizzoni considered himself as not entitled to interfere in the painter’s personal style, but was picky about diligence. Vrubel subsequently wrote that «I have not heard from many people so much fair but benevolent criticism».[88]

In winter 1892, Vrubel decided to participate in the Paris Salon where he got an idea for the painting «Snow-maiden» (not preserved). Elizaveta Mamontova later wrote:

I visited Vrubel, he painted a life-size Snow Maiden’s head in watercolour against the background of a pine tree covered with snow. Beautiful in colours, but the face had gumboil and angry eyes. How ironic, he had to come to Rome to paint the Russian winter.[89]

Vrubel continued to work in Abramtsevo. He returned from Italy with an idea to draw landscapes from photographs which resulted in a single earning of 50 rubles.[90] One of his most significant works after the return was the panel «Venice» that was also painted based on the photograph. The main feature of this composition is its timelessness – it is impossible to say when the action took place. The figures were chaotically arranged, «compressing» space, which is projected onto the plane. A pair for the Venice became the «Spain» which critics recognize as one of the Vrubel’s most perfectly arranged paintings.[91]

Decorative works[edit]

Vrubel spent the winter of 1892–1893 in Abramtsevo. Due to regular commissioned works made for Mamontov, Vrubel’s reputation in Moscow grew greatly. For instance, the painter received the order to decorate the Dunker family mansion on the Povarskaya Street. Also, together with the most famous architect of Moscow Art Nouveau Fyodor Schechtel, Vrubel decorated the Zinaida Morozova’s mansion on Spiridonovka street and A. Morozov’s house in Podsosenskiy lane.[92]

Vrubel’ decorative works illustrate how universal his talents were. The painter combined painting with architecture, sculpture and applied art. Karpova recognized his leading role in creating ensembles of Moscow Modern. Vrubel’s sculpture attracted the attention of his contemporaries. For instance, at the end of his life, Aleksandr Matveyev mentioned that «without Vrubel there would be no Sergey Konenkov…».[93]

The gothic composition «Robert and the Nuns» is usually considered as the most important Vrubel’s sculpture; it decorates the staircase of the Morozov mansion.[93] Literature on architecture emphasizes the exclusive role that Vrubel played in forming artistic appearances of the Moscow Art Nouveau. The artist created several compositions (small sculptural plastics from maiolica and tiles) which decorated important buildings in modern and pseudo-Russian style (Moscow Yaroslavsky railway station, Osobnyak M. F. Yakunchikovoy [ru], Dom Vasnetsova [ru]). The Mamontov’s mansion on Sadovaya-Spasskaya street was built exactly according to Vrubel’s architectural ideas; he also headed several other projects, such as the church in Talashkino and exhibition pavilion in Paris.[94][95]

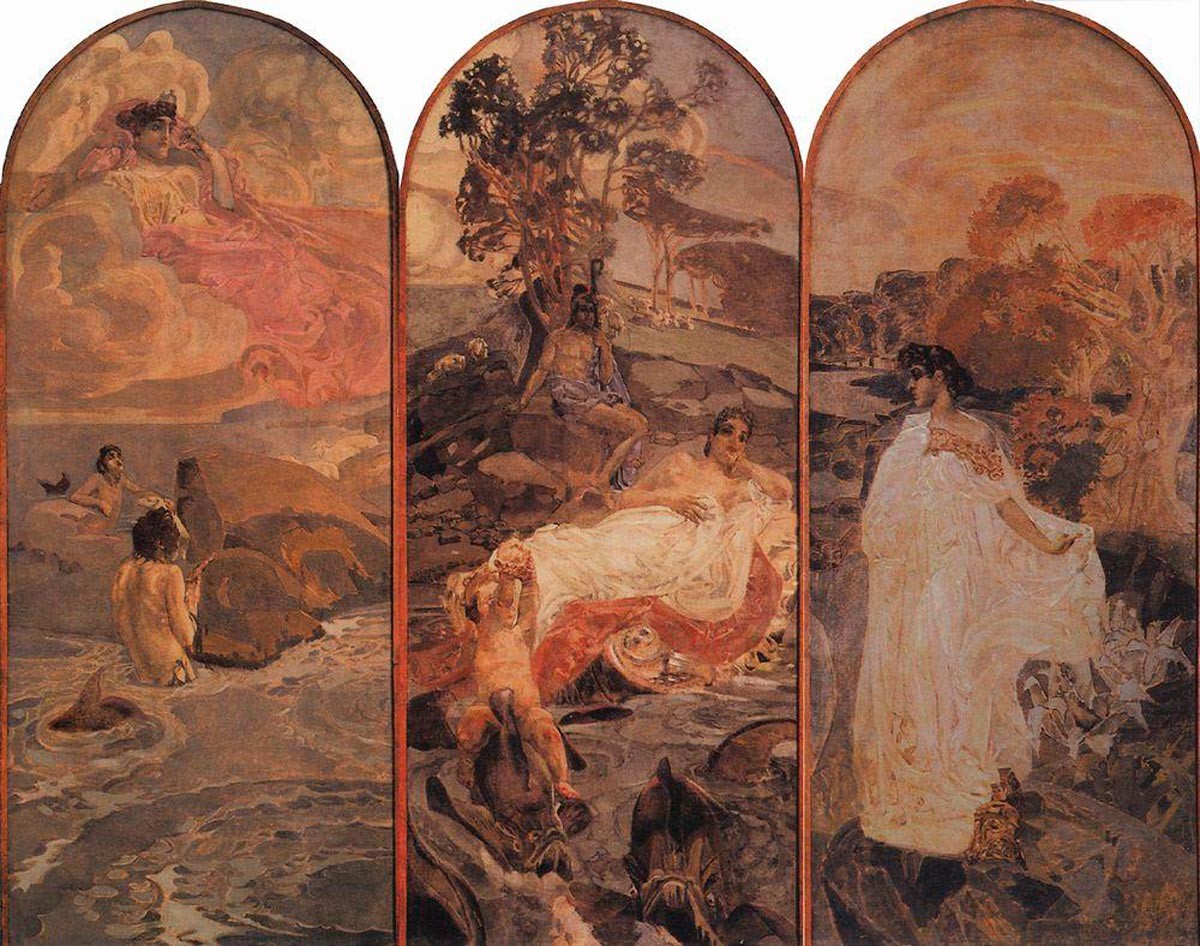

The Judgement of Paris, 1893

Until November 1893, Vrubel worked on «The judgement of Paris» that was supposed to decorate the Dunker’s mansion. Yaremich later defined this work as a «high holiday of art».[96] However, customers rejected both «Paris» and the hastily painted «Venice». A well-known collector Konstantin Artsybushev [ru] later bought both works. He also set up a studio in his house on Zemlyanoy Val street where Vrubel stayed for the first half of the 1890s. At that time, Anna Vrubel relocated to Moscow from Orenburg and was able to see her brother more often.[97]

In 1894, Vrubel plunged into severe depression, and Mamontov sent him to Italy to look after his son Sergei, a retired hussar officer who was supposed to undergo treatment in Europe (he suffered from hereditary kidney disease and underwent a surgery). Thus, the Vrubel’s candidature seemed very suitable – Mikhail could not stand gambling and even left the casino in Monte Carlo, saying «what a bore!».[98] In April, after coming back to Odessa, Vrubel again found himself in a situation of chronic poverty and family quarrels. Then he once again came back to maiolic art while creating the Demon’s head. Artsybushev bought this work, and with the money received, Vrubel returned to Moscow.[99]

Approximately at the same time, Vrubel painted «The Fortune Teller» in one day, following the strong internal desire. The composition is similar to the portrait of Mani Dakhnovich – the model also sits in the same pose against the carpet. Black haired woman of Eastern type does not pay attention to cards and her face remains impenetrable. In terms of colours, the focus is on a pink scarf on the girl’s shoulders. According to Dmitrieva, even though traditionally pink is associated with serenity, the scarf looks «ominous».[91] Presumably, the model for «The Fortune Teller» was one of the artist’s lovers of Siberian origin. Even in this painting, Vrubel was inspired by the opera Carmen from which he borrowed an unfortunate divination outcome – ace of spades. The painting was painted over the destroyed portrait of the Mamontov’s brother Nicolai.[100]

Vrubel continued to follow his bohemian lifestyle. According to Korovin’s memoirs, after getting a large salary for watercolour panels, he spent them as follows:

He organized the dinner in the hotel «Paris» where he also lived. He invited everyone who stayed there. When I joined after the theatre, I saw tables covered with bottles of wine, champagne, a lot of people, among guests – gypsies, guitarists, an orchestra, some military men, actors, and Misha Vrubel treated everyone like a maître d’hôtel pouring champagne from the bottle that was wrapped in a napkin. «How happy I am,» he told me. «I feel like a rich man.» See how well everyone feels and how happy they are.

Five thousand rubles gone, and it still was not enough to cover the expenses. Thus, Vrubel worked hard for the next two months to cover the debt.[101]

Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod, 1896[edit]

In 1895, Vrubel attempted to gain authority among Russian art circles. In February, he sent the «Portrait of N. M. Kazakov» to the 23rd exhibition of Peredvizhniki movement – however, the painting was rejected for exposure. In the same season, he managed to participate in the third exhibition of the Moscow Association of artists [ru] with his sculpture «The Head of Giant» thematically dedicated to the poem Ruslan and Ludmila. The newspaper «Russkiye Vedomosti» critically engaged with the painting and benevolently listed all the exhibitors except for Vrubel who was separately mentioned as an example of how to deprive the plot of its artistic and poetic beauty.[102]

Later Vrubel participated in the All-Russia Exhibition 1896 dedicated to the Coronation of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna. Savva Mamontov was a curator of the exposition dedicated to the Russian North. It was him who noticed that the neighbouring section of arts lacks the paintings that would cover two large empty walls. Mamontov discussed with the Minister of Finance his idea to cover these walls with large panels with total area 20 × 5 m and ordered these panels from Vrubel.[103] At that time, the painter was busy decorating the Morozov’s mansion in Moscow. However, he agreed to take the offer even though the order was quite big – the total area of paintings was 100 square meters, and it needed to be finished in three months.[104] He planned to decorate the first wall with the painting «Mikula Selyaninovich» that metaphorically depicted the Russian land. For the second wall, Vrubel chose «The Princess of the Dream» inspired by a work of the same name made by the French poet Edmond Rostand. The second painting symbolically represented the painter’s dream of beauty.[105]

It was impossible to complete the order in such short notice. That is why Vrubel instructed painter T. Safonov from Nizhny Novgorod to start working on «Mikula». Safonov was supposed to paint according to Vrubel’s sketches. The decorative frieze was finished by A. Karelin – son of a Russian photographer Andrei Karelin.[106]

On March 5, 1896, academician Albert Nikolayevitch Benois reported to the Academy of Arts that the work that was being carried out in the art pavilion is incompatible with its thematic goals. Thus, Benois demanded from Vrubel sketches of the alleged panels. After arriving in Nizhny Novgorod on April 25, Benois sent a telegram:

Vrubel’s panels are terrifying; we need to take them off, waiting for the juri.[107]

On May 3, the committee of the Academy arrived in Petersburg. The committee included Vladimir Aleksandrovich Beklemishev, Konstantin Savitsky, Pavel Brullov, and others. They concluded that it is impossible to exhibit Vrubel’s works. Mamontov told Vrubel to continue working and went to Saint Petersburg to persuade the members of the committee. At the same time, while trying to put the plot of «Mikula Selyaninovich» on a canvas, Vrubel realized that he previously was not able to proportionate the figures properly. Thus he started to paint the new version right on the stage of the pavilion. Mamontov attempted to protect the painter and called for the convening of the new committee. However, his claims were rejected, and on May 22 Vrubel had to leave the exhibition hall while all of his works had been already taken.[108]

Vrubel lost nothing financially since Mamontov bought both paintings for 5 000 rubles each. He also agreed with Vasily Polenov and Konstantin Korovin for them finishing the half-ready «Mikula». Canvases were rolled up and brought back to Moscow where Polenov and Korovin started working on them while Vrubel was finishing «The Princess of the Dream» in a shed of the Abramtsevo Pottery factory. Both canvases arrived in Nizhny Novgorod right before the emperor’s visit scheduled on July 15–17. Besides two giant panels, Vrubel’s exposition included «The head of Demon», «The head of Giant», «The Judgement of Paris» and «Portrait of a Businessman K. Artsybushev».[109] Subsequently, during the construction of the Hotel Metropol, one of the fountains facing Neglinnaya Street was decorated with maiolica panel that reproduced «The Princess of the dream». The panel was made at the Abramtsevo’s studio upon Mamontov’s order.[110]

At that time, Mikhail Vrubel travelled to Europe to deal with marital affairs while Mamontov remained in charge of all his affairs in Moscow.[109] He built a special pavilion named the «Exhibition of decorative panels made by Vrubel and rejected by the Academy of Arts».[105] That is how big debates in newspapers had started. Nikolai Garin-Mikhailovsky was the first who published the article «Painter and the jury» in which he carefully analyzed Vrubel’s art without any invectives. On the contrary, Maxim Gorky was against Vrubel. He made fun of «Mikula» by comparing it with a fictional character Chernomor. «The Princess of the Dream» resent him with its «antics, ugliness of otherwise beautiful plot». In five articles, Gorky exposed Vrubel’s «poverty of spirit and poverty of imagination».[111]

The Lilacs, 1900. Stored at the Tretyakov Gallery

Later Korovin mentioned in his memoir the anecdote that illustrates how officials reacted to the scandal:

When Vrubel became ill and was hospitalized, the Sergei Diaghilev ‘s exhibition opened in the Academy of Arts. The emperor also was at the opening ceremony. Once he saw the Vrubel’s «The Lilacs», he said:

– How beautiful it is. I like it.

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia who was standing nearby, heatedly debated:

– What is this? This is a decadence…»

– No, I like it, – replied the emperor – Who is the author?

– Vrubel – was the reply.

…Turning to the retinue and noticing the vice-president of the Academy of Arts Count Ivan Ivanovich Tolstoy, the emperor said:– Count Ivan Ivanovich, is this the one who was executed in Nizhny?…[112]

Wedding. Further work (1896–1902)[edit]

At the beginning of 1896, Vrubel travelled from Moscow to Saint Petersburg to pay a visit to Savva Mamontov. Around the same time, the Russian premiere of the fairy-tail opera «Hansel and Gretel» was about to take place. Savva Mamontov got carried away by this staging and even personally translated the libretto as well as sponsored the combination company of the Panaevski theatre [ru]. Among the expected performers was prima Tatiana Lubatovich [ru]. Originally, Konstantin Korovin was responsible for the decorations and costumes but because of illness had to renounce the order in favour of Mikhail Vrubel who had never even attended an opera before. On one of the rehearsals, the painter saw Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel who played the role of Gretel’s little sister.[113] This is how Nadezhda Zabela later recalled her first meeting with Mikhail:

On the break (I remember that I stood behind the curtain), I was shocked that some man ran to me and, kissing my arm, exclaimed: “What an amazing voice!”. Standing nearby Tatiana Lubatovich harried to introduce him to me: “This is our painter Mikhail Vrubel”, and, aside she told me: A very noble person but a bit expansive.[114]

Mikhail and Nadezhda Vrubel, 1896

Vrubel proposed to Nadezhda shortly after the first meeting. In one of his letters to Anna Vrubel, he mentioned that he would kill himself immediately if Nadezhda rejected his proposal.[114] The meeting with the Zabela family did not go very well since her parents were confused with the age difference (he was 40 years old, and she was 28 years old). Even Nadezhda herself was familiar with the fact that «Vrubel drinks, is very erratic about money, wastes money, have an irregular and unstable income».[115] Nevertheless, on July 28 they engaged in the Cathedral of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross in Geneva, Switzerland. The couple spent their honeymoon in a guesthouse in Lucerne. Then Vrubel continued his work on the panel for the Morozov’s gothic cabinet. At the point of their engagement, Vrubel was utterly broke and even had to go from the station to Nadezhda’s house by walk.[116]

For the fall of 1896, Nadezhda Zabela Vrubel had a short contract with the Kharkiv opera. However, Vrubel did not many commissions in the city and had to live on his wife’s money. This prompted him to turn to theatrical painting and costume designs. According to the memoirs of his acquaintances, Vrubel started designing costumes for Nadezhda, redoing costumes for Tatiana Larina.[117] As was noted by Dmitrieva, Vrubel owes the fruitfulness of the Moscow period to Nadezhda and her admiration with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.[118] They personally met each other in 1898 when Nadezhda was invited to the Moscow private opera.[119] Zabela remembered that Vrubel listens to the opera «Sadko» in which she sang the role of Princess of Volkhov no less than 90 times. When she asked him if he was tired of it, he replied: “I can endlessly listen to the orchestra, especially the sea part. Every time I find in it a new wonder, see some fantastic tones.[120]

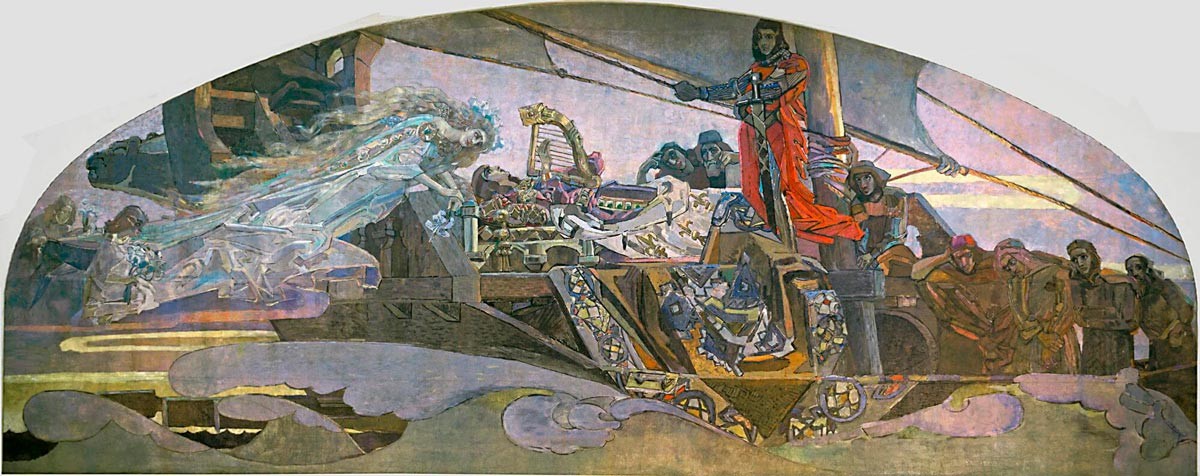

Morning, 1897. Stored at the Russian Museum

During his stay in St. Petersburg in January 1898, Ilya Repin advised Vrubel not to destroy the panel Morning that was rejected by the commissioner but instead try to expose it at any other exhibition. As a result, the panel was exhibited at the display of Russian and Finnish painters organized by Sergei Diaghilev in the museum of Saint Petersburg Art and Industry Academy.[121]

In 1898, during the summer stay in Ukraine, Vrubel experienced several symptoms of his future disease. His migraines got so strong that the painter had to take phenacetin in large quantities (according to his sister in law – up to 25 grains and more). Mikhail started to experience intense anxiety, especially if somebody did not agree with his opinion on a piece of art.[122]

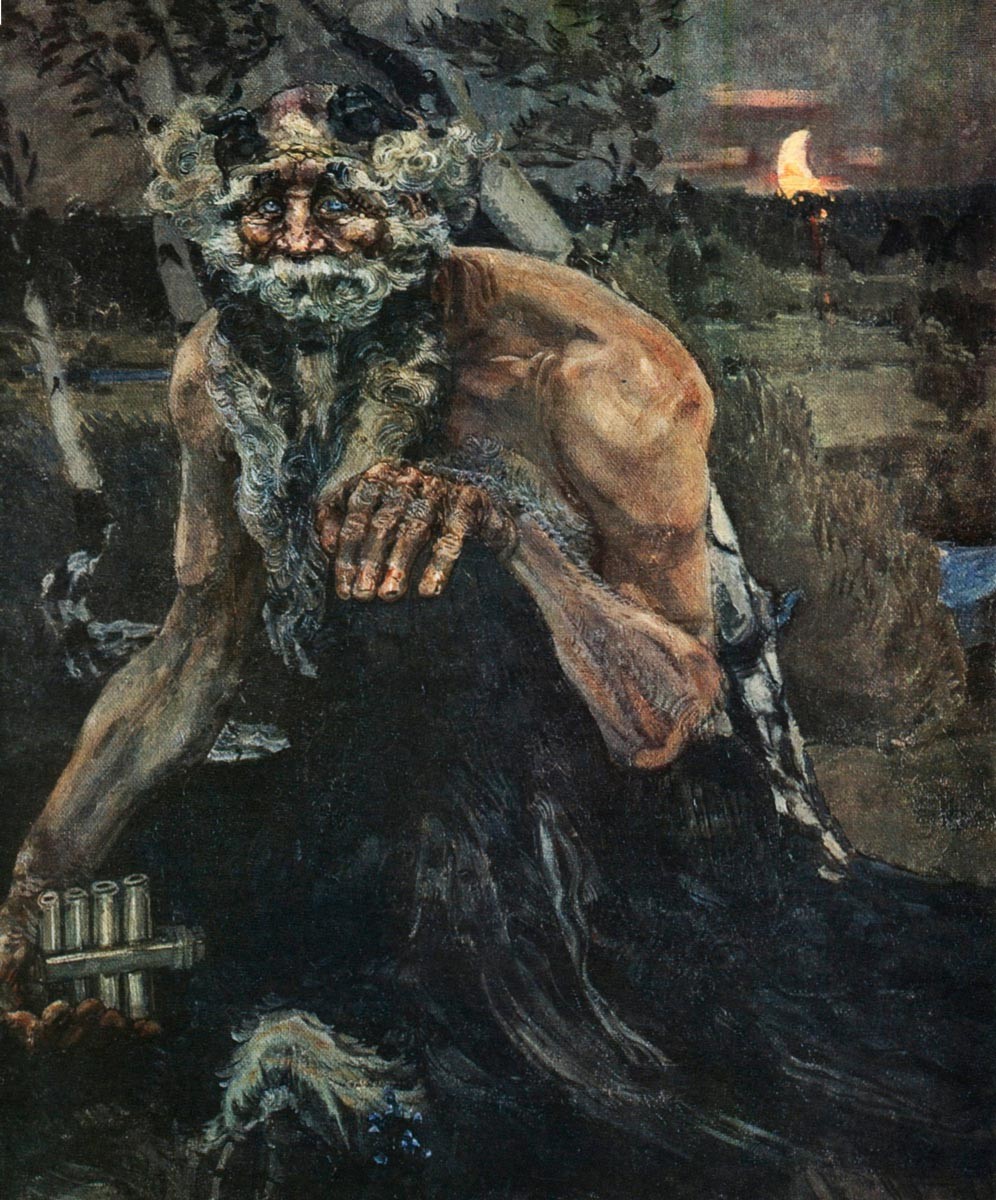

In the last years of the XIX century, Vrubel referred to fairy-mythology plots, particularly Bogatyr, Pan, Tsarevna-Lebed.

‘Pan’, Mikhail Vrubel, 1899, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow Russia, 124×106.3 cm.

In the painting ‘Pan’ of 1899, Vrubel has used a mythological figure to show the organic unity of man and nature. The figure does not resemble the erotic image of eternal youth that is known in the West: It resembles a figure from Russian folklore knows as the ‘leshiy’, which is the Russian spirit of the forest.[123] The creature has a bushy beard, a strong, bulky figure and is known to be mischievous. This figure is said to be as tall as the trees and in the stories he is known to trick travellers, but only as a game because he is good-natured.[124] The cheeky-ness of the creature sparks through in his eyes. The creature is placed within a twilight, which hints to the awakening of mysterious forces in nature, which are maintained by rich vegetation and its manifestation: Pan. Pan serves as a symbol for nature; the abundance and vividness of nature. This symbol is also visualized in the depiction of the body of the figure: His body appears to be growing out of a stump and the curls in his hair and his curled fingers look like the knots and gnarls of an oak tree.[125] The lightning Vrubel chose to incorporate and which shines lightly on the figure creates a mysterious atmosphere. The painted pale moon enhances this feeling.[126]

The eyes of the figure tell a story, they reveal the “psychic life of the figures”.[127] They seem to look directly at the viewer, as if the creator has prophetic awareness: Senses that mortals do not have, they are out of this world. The blue eyes of the creature mirror the water in the swamp behind him.

The painter was able to finish Pan in one day while being in Tenisheva’s mansion in Talashkino. The plot was drawn in a canvas on which he previously started to paint the portrait of his wife. The painting was inspired by the literature novella "Saint Satyr" by Anatole France.[128] With great difficulty, he was able to expose his paintings at the Diaghilev's exhibition. It was already after his paintings were shown at the Moscow Association of Artists’ exhibition, where they did not receive the attention.[129]

‘the Bogatyr’, 1898, Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia, oil on canvas, 321,5 x 222 cm.

In 1898 Vrubel painted ‘the Knight’ or ‘the Bogatyr’. In this painting Vrubel portrays a bogatyr from old Russian folklore, which differs from the pre-Raphaelite Western knights that are predominantly elegant and overrefined.[130] This figure is weighty and strong with a beard and rough hands who is ready to plough the fields as well as fight. This painting is most likely inspired by the famous Russian epic figure ‘Ilya of Murom’, who is said to have defeated supernatural monsters and whose horse couple jump higher than the tallest of trees and only a little lower than the clouds in the sky.[131] In the bylina in which the story of Ilya of Murom is described it reads: “While resting on the earth, Ilia’s power grew three times.”[132] Vrubel has referred to Byliny, which are ancient Slavic tales about various famous heroes, in other interior decoration works that he made when he was staying at Abramtsevo.[133] In Russia, Ilya Muromet is associated with incredible physical strength and spiritual power and integrity, with as its main goal in life the protection of the Russian homeland and its people.[134]

The patterns visible in the bogatyr’s kaftan, chain mail and boots resemble that of war saints in old Russian icons.[135] The landscape of the painting has ornamental qualities which remind of Bakst productions such as ‘The Afternoon with the Faun’.[136]

The figure of the Bogatyr is also represented in the Romantic painter Vasnetov’s ‘Bogatyrs’. This painting however lacks the spiritual and fantastical qualities that Vrubel’s painting possesses. Vrubel wanted not only to express the power for the Russian land, like Vasnetov, but also ‘the enchanting atmosphere of silent metamorphosis: the archaic “belonging to the land” in the image of the Bogatyr’.[137] The figure of the bogatyr in Vrubel’s painting can be interpreted as a representation of nature turned human, at least it feels an intimate part of it.[138] The bogatyr is native in his surroundings. Vrubel tried to make the figure of the bogatyr and the background a whole. For Vrubel, the unification of the background and the symbols was typical.[139] The bogatyr is part of the abundant power and spiritual quality of nature; the nature that is often poetized in folklore.[140]

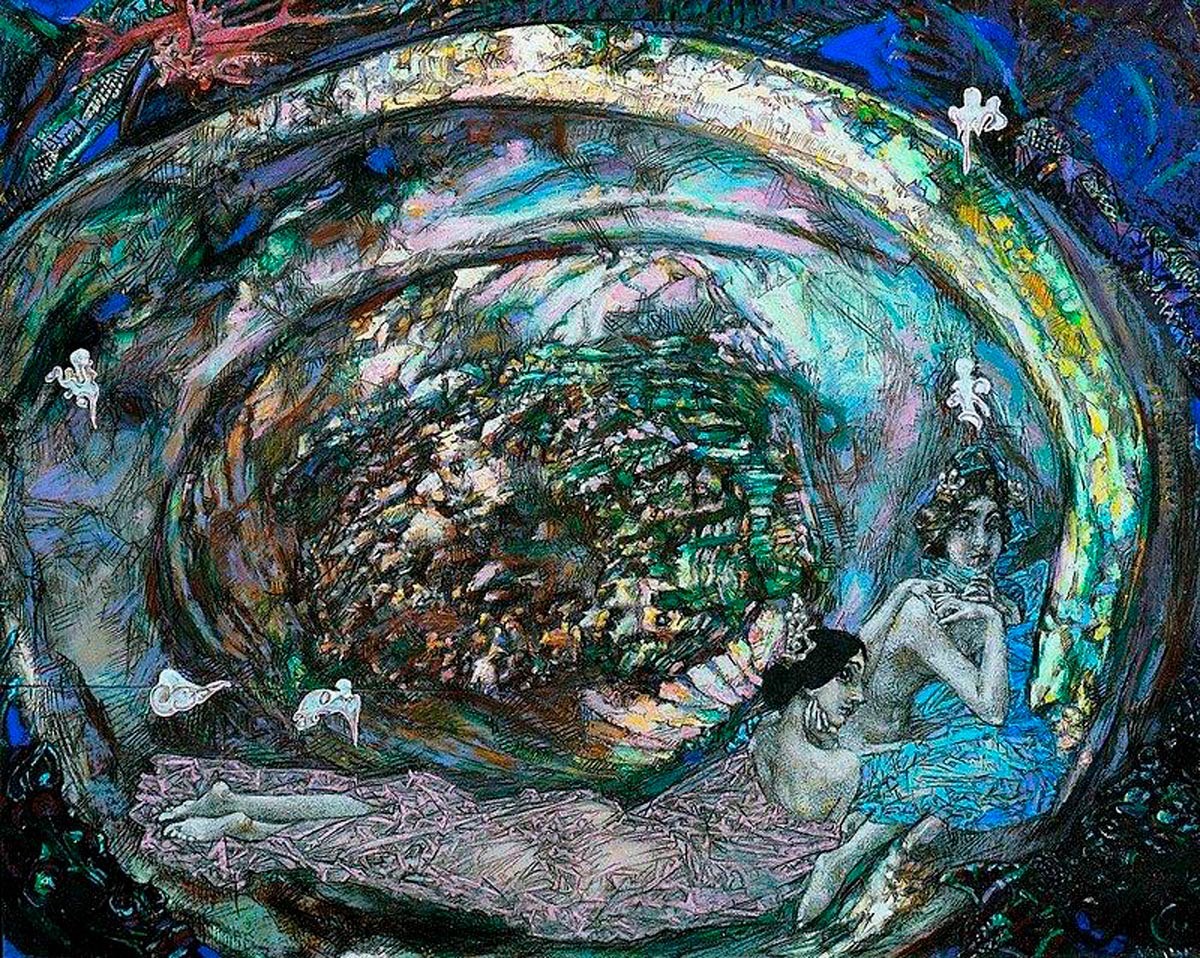

There is a conventional view that the painting the «Swan Princess» («Tsarevna-Lebed») was inspired by the opera staging. However, the canvas was finished in spring while rehearsals for The Tale of Tsar Saltan took place in fall with the premiere on December 21, 1900.[141] The merit of this painting was widely debated since not all of the critics recognized it as a masterpiece.[142] Dmitrieva characterized this work as follows: «Something is alarming about this painting – it was not without a reason that it was the favourite painting of Alexander Blok. In the gathering twilight with a crimson strip of sunset, the princess floats into darkness and only for the last time turned to make her strange warning gesture. This bird with the face of a virgin is unlikely to become Guidon’s obedient wife, and her sad farewell gaze does not promise. She does not look like Nadezhda Zabela – it is a completely different person, even though Zabela also played this role in «The Tale of Tsar Saltan».[143] Nicolai Prakhov [ru] found in the face of Tsarevna-Lebed resemblance to his sister Elena Prakhova [ru]. However, the painting most likely originated in a collection image of Vrubel’s first love Emily Prakhova, Nadezhda Vrubel and, presumably, of some else.[144]

The dish «Sadko», 1899–1900

In the middle of summer 1900, Mikhail Vrubel found out that he was awarded the gold medal at the Exposition Universelle for the fireplace «Volga Svyatoslavich and Mikula Selyaninovich». Besides Vrubel, gold medals were given to Korovin and Filipp Malyavin, while Serov won the Grand Prix. At the exhibition, Vrubel’ works (mostly applied ceramics and maiolica art) were exhibited at The Palace of Furniture and Decoration.[145] Later, the artist reproduced the fireplace «Volga Svyatoslavich and Mikula Selyaninovich» four times; however, only one of them in the House of Bazhanov was put to its intended use. In those same years, Vrubel worked as an invited artist in the Dulyovo porcelain factory. His most famous porcelain painting was the dish «Sadko».[146]

The Demon Downcast[edit]

Ten years later, Vrubel returned to the theme of Demon which is evident from his correspondence with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov at the end of 1898. Starting from the next year, the painter was torn between the paintings «Flying Demon [ru]» and «The Demon Downcast». As a result, he chose the first variant, but the painting remained unfinished. The painting and several illustrations were inspired by intertwined plots of Lermontov’s Demon and Pushkin’s «The Prophet».[147]

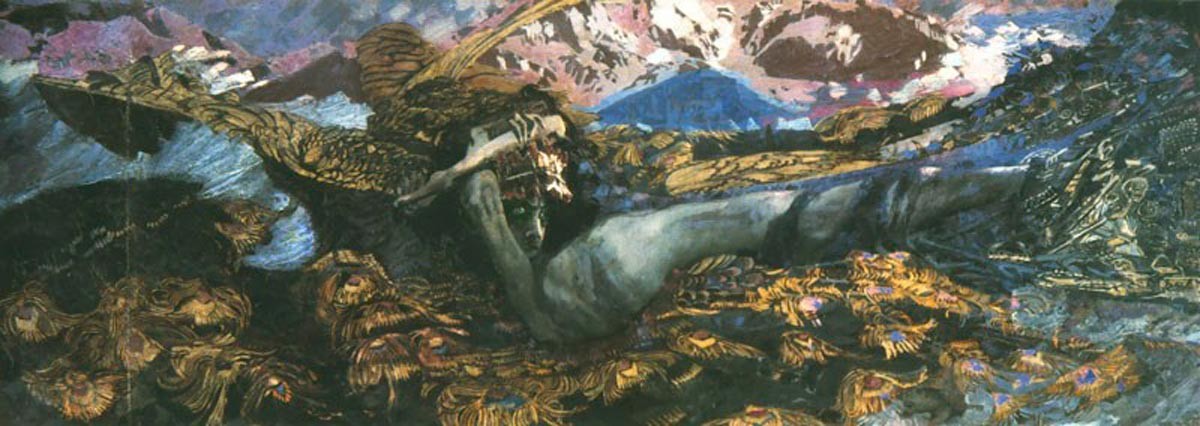

In the painting we see the Demon thrown in the mountains, surrounded by a swirling chaos of colours. The Demon’s body is broken, but his eyes still stare brightly at us, as if undefeated.[148] The elongated body of the Demon almost looks deformed, as the body is depicted in unusual, unnatural proportions. This gives the impression that the body is suffering and affected by the power of nature surrounding him.[149] The painting reminds of despair: The chaos surrounding the Demon, the Demon’s ‘ashen’ face and the faded hues.[150] This painting seems a representation of Vrubel’s inner world and his forthcoming insanity.[151]

In ‘Demon Cast Down’, it seems Vrubel refers to religious figures. The Demon wears something that can be interpreted as a crown of thorns, which could refer to Christ’s passion and the suffering he endured.[152] Here Vrubel is mixing the figure of the Demon, which is often associated with evil, with Crhist, which is peculiar. The metallic powder Vrubel used resembles the Byzantine mosaics that had inspired him.[153] Moreover, Vrubel’s intention was to exhibit his Demon cast Down under the title ‘Icone’,[154] hereby directly referring to Byzantine religious art and thus it should be read accordingly: As its main purpose to bring the viewer to a higher spiritual world.

On September 1, 1901, Nadezhda gave birth to a son named Savva. The baby boy was born strong with well-developed muscles but had an orofacial cleft. Nadezhda’s sister, Ekaterina Ge, suggested that Mikhail had «a particular taste hence he could find beauty in a certain irregularity. And this child, despite his lip, was so cute with his big blue eyes that his lip shocked people only in the first moment and then everyone would forget about it».[155]

While working on «Demon», the painter created the large watercolour portrait of a six-month child sitting in a baby carriage. As Nikolai Tarabukin later recalled:

The scared and mournful face of this tiny creature flashed like a meteor in this world and was full of unusual expressiveness and some childish wisdom. His eyes, as if prophetically, captured the whole tragic fate of his fragility.[155]

The birth of Savva led to a dramatic change in the routine of the family. Nadezhda Vruble decided to take a break in her career and refused to hire a nanny. Hence, Mikhail Vrubel had to support his family. Starting from September–October 1901, Vrubel had experienced first depression symptoms due to drastically increased number of working hours. Starting from November, he stopped working on «The Demon Downcast». Vrubel’s biographer later wrote:

For the whole winter Vrubel worked very intensively. Despite usual 3–4 hours, he worked up to 14 hours, and sometimes even more, with a flash of artificial lightning, never leaving the room and barely coming off the painting. Once a day he put up a coat, opened window leaf and inhaled some cold air – and called it his «promenade». Fully engaged in work, he became intolerant to any disturbance, did not want to see any guests and barely talked to the family. The Demon was many times almost finished, but Vrubel re-painted it over and over again.[156]

Demon Downcast, 1902. Stored at the Tretyakov Gallery

As Dmitrieva noted: «This is not his best painting. It is unusually spectacular, and was, even more, striking upon its creation when the pink crown sparkled, the peacock feathers flickered and shimmered (after a few years, the dazzling colours began to darken, dry up and now almost blackened). This exaggerated decorative effect itself deprives the painting of actual depth. To amaze and shock, the artist, who had already lost his emotional balance, betrayed his “cult of a deep nature” – and The Demon Dawncast, from the purely formal side, more than any other paintings by Vrubel, was painted in the modern style».[157]

Vrubel’s mental health continued to worsen. He started suffering from insomnia, from day to day, his anxiety increased, and the painter became unusually self-confident and verbose. On February 2, 1902, unsuccessful exposition of «The Demon Downcast» in Moscow (the painter hoped that the painting would be bought for the Tretyakov Gallery) coincided with a suicide of Alexander Rizzoni following incorrect criticism in the «Mir isskusstva».[158]

Then the painting was brought to Saint Petersburg where Vrubel continued to constantly re-paint it. However, according to his friends, he only damaged it. Due to the painter’s anxiety, his friends brought him to a famous psychiatrist Vladimir Bekhterev who diagnosed Vrubel with an incurable, progressive paralysis or tertiary syphilis. Mikhail Vrubel travelled to Moscow without knowing the diagnosis where his condition only worsened.[159] His painting was bought for 3 000 rubles by the famous collector Vladimir von Meck [ru]. Judging by the correspondence between Nadezhda Zabela and Rimsky-Korsakov, Vrubel got crazy, drank a lot, wasted money and quickly broke off for any reason. His wife and son tried to escape him and ran to relatives in Ryazan, but he followed them. At the beginning of April, Vrubel was hospitalized to a private hospital run by Savvy Magilevich.[160]

Disease. Dying (1903–1910)[edit]

The first crisis[edit]