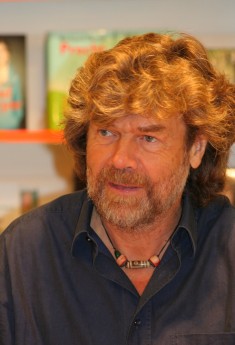

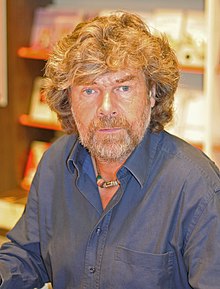

| Reinhold Messner | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Mountaineer | |

| Specialty | Ascent of Mt. Everest |

| Born | Sep. 17, 1944 Brixen, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

Reinhold Messner is a famous mountaineer, explorer, and adventurer from Italy. His astonishing achievements of climbing Mount Everest and other great peaks in the world have helped him become one of the most recognized and celebrated mountaineers of all time.

Early Years

Born in Bixen, Italy, Messner grew up in South Tyrol and climbed the Alps in the early years of life as his love for mountains and mountaineering grew. Joseph Messner, his father, was a teacher and he led Reinhold for his first climb when Reinhold was only five years old.

Reinhold had a big family with eight brothers and one sister. He speaks Italian, German, and English languages. At the age of 13, Reinhold started climbing with his younger brother, Gunther. They both shared the liking for mountaineering and when they reached their twenties, both Reinhold and Gunther had a reputation of being the best mountaineers in Europe.

Messner’s Early Climbing Adventures

Reinhold Messner carried out various expeditions and was the first individual to climb all 14 summits in the world above that measured at least 8000 meters (from sea level). He has several accolades and records to his name, which makes him one of the best climbers ever. He also became first one individual to climb Mount Everest without using supplementary oxygen.

In addition to that, Reinhold Messner also became the first individual to climb Mount Everest solo. Apart from scaling mountains, Messner has also crossed the Gobi Desert, covering more than 2000 kilometers. He has also crossed Antarctica on skis, along with Arven Fuchs, a fellow explorer. Messner has written more than 60 books about his experiences. He has also featured in a film – The Dark Glow of the Mountains.

Nanga Parbat Expedition

The 1970 expedition to Nanga Parbat was from the unclimbed Rupal face, which was the highest rock-face in the world. Before this expedition, only one person had climbed Nanga Parbat, but from the Diamir face.

The Rupal face was extremely difficult to conquer. Reinhold went on to achieve this difficult task, but while coming down from the Diamir face, he lost his younger brother Gunther in an avalanche. Messner managed to survive with severe frostbite, but lost seven of his toes in the process. Later on, after three unsuccessful expeditions, Messner climbed Nanga Parbat solo from the Diamir side in 1978.

Messner took several successful expeditions to mountains that had peaks of at least 8000 meters in height, such as K2, Annapurna, Lhotse, Kanchenjunga, Mount Doom, Broad Peak, both Gasherbrums, Dhaulagiri, Makalu, Manaslu, Cho Oyu and Shishapangma.

Messner’s Everest Expedition

To reiterate, Reinhold Messner is known for making the first solo ascents of Mount Everest without using supplementary oxygen. In 1978, Reinhold Messner scaled the heights of Mount Everest along with Peter Habeler to set that record. In 1980, he again climbed Everest without bottled oxygen, but that time he did it solo.

On his second expedition of Mount Everest, he took a never-before climbed route and finished it in four days, which is arguably the most astounding feat in mountaineering history. During his Everest expeditions, he set new technical standards and pioneered fast solo ascents.

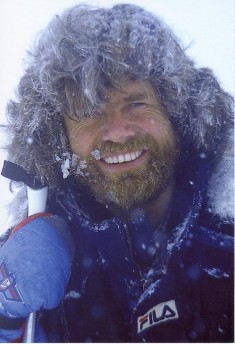

Expedition to Antarctica

From 1989 to 1990, Reinhold Messner organized a man hauling “Würth-Antarktis Transversale” to cross the Antarctica Continent. He crossed the German Filchner Station on the Ronne Ice Shelf and arrived at Patriot Hillslet’s go. Due to the problems with ANI fuel and flight arrangements, the trip was shortened and there were modifications in the original expedition plan. In his book – Antarctica: Both Heaven and Hell – Messner has included his experiences as well as the photos during his Antarctica expedition.

Other Major Publications

Messner has written a large number of books on his climbing experiences. Some of his most popular books include Everest: Expedition to the Ultimate, All 14 Eight Thousanders, Annapurna: 50 Years of Expeditions in the Death Zone, and many more.

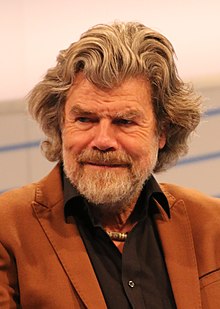

Current Life and Legacy

Reinhold Messner has lived a remarkable life with true spirit of an explorer and adventurer. He has loved what he does and he lived and respected the challenges that nature throws at mankind.

Currently, Reinhold runs diversified business related to mountaineering. He had a stint in politics as well as the Member of European Parliament. He currently spends most of his time at the Messner Mountain Museum, which he founded.

Reinhold Andreas Messner (German pronunciation: [ˈʁaɪ̯nhɔlt ˈmɛsnɐ]) (born 17 September 1944) is an Italian mountaineer, explorer, and author from South Tyrol. He made the first solo ascent of Mount Everest and, along with Peter Habeler, the first ascent of Everest without supplemental oxygen. He was the first climber to ascend all fourteen peaks over 8,000 metres (26,000 ft) above sea level. Messner was the first to cross Antarctica and Greenland with neither snowmobiles nor dog sleds.[1] He also crossed the Gobi Desert alone.[2]

Messner has published more than 80 books about his experiences as a climber and explorer. In 2018, he received jointly with Krzysztof Wielicki the Princess of Asturias Award in the category of Sports.

Early life and education[edit]

Reinhold Messner in June 2002

Messner was born within a German-speaking family settled in St. Peter, Villnöß, near Brixen in South Tyrol which is part of Northern Italy. According to his sister his delivery was difficult as he was a large baby and birth took place during an air raid. His mother Maria (1913–1995) was the daughter of a shop owner and 4 years older than her husband. His father Josef (1917–1985) was drafted to serve the German army and participated in WW II at the Russian front. After the war he was an auxiliary teacher until 1957, when he became the director of the local school.

Messner was the second of nine children – Helmut (born 1943), Günther (1946–1970), Erich (born 1948), Waltraud (born 1949), Siegfried (1950–1985), Hubert (born 1953), Hansjörg (born 1955) and Werner (born 1957) and grew up in modest means.[3][4]

Messner spent his early years climbing in the Alps and falling in love with the Dolomites.

His father was strict and sometimes severe with him.[citation needed] He led Reinhold to his first summit at the age of five.[citation needed]

When Messner was 13, he began climbing with his brother Günther, age 11. By the time Reinhold and Günther were in their early twenties, they were among Europe’s best climbers.[5]

Since the 1960s, Messner, inspired by Hermann Buhl, was one of the first and most enthusiastic supporters of alpine style mountaineering in the Himalayas, which consisted of climbing with very light equipment and a minimum of external help. Messner considered the usual expedition style («siege tactics») disrespectful toward nature and mountains.[citation needed]

Career[edit]

Before his first major Himalayan climb in 1970, Messner had made a name for himself mainly through his achievements in the Alps. Between 1960 and 1964, he led over 500 ascents, most of them in the Dolomites.[citation needed] In 1965, he climbed a new direttissima route on the north face of the Ortler.[citation needed] A year later, he climbed the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses and ascended the Rocchetta Alta di Bosconero. In 1967, he made the first ascent of the northeast face of the Agnér and the first winter ascents of the Agnér north face and Furchetta north face.[citation needed]

In 1968, he achieved further firsts: the Heiligkreuzkofel middle pillar and the direct south face of the Marmolada. In 1969, Messner joined an Andes expedition, during which he succeeded, together with Peter Habeler, in making the first ascent of the Yerupaja east face up to the summit ridge and, a few days later, the first ascent of the 6,121-metre-high (20,082 ft) Yerupaja Chico.[6] He also made the first solo ascent of the Droites north face, the Philipp-Flamm intersection on the Civetta and the south face of Marmolada di Rocca. As a result, Messner won the reputation of being one of the best climbers in Europe.

In 1970, Messner was invited to join a major Himalayan expedition that was going to attempt the unclimbed Rupal face of Nanga Parbat. The expedition, which was the major turning point in his life, turned out to be a tragic success. Both he and his brother Günther reached the summit but Günther died two days later on the descent of the Diamir face. Reinhold lost seven toes, which had become badly frostbitten during the climb and required amputation.[5][7] Reinhold was severely criticized for persisting on this climb with the less experienced Günther.[8] The 2010 movie Nanga Parbat by Joseph Vilsmaier is based on his account of the events.[9]

While Messner and Peter Habeler were noted for fast ascents in the Alps of the Eiger North Wall, standard route (10 hours) and Les Droites (8 hours), his 1975 Gasherbrum I first ascent of a new route took three days. This was unheard of at the time.[citation needed]

In the 1970s, Messner championed the cause for ascending Mount Everest without supplementary oxygen, saying that he would do it «by fair means» or not at all. In 1978, he reached the summit of Everest with Habeler. This was the first time anyone had been that high without supplemental oxygen and Messner and Habeler achieved what certain doctors, specialists, and mountaineers thought impossible. He repeated the feat, without Habeler, from the Tibetan side in 1980, during the monsoon season. This was Everest’s first solo summit.

Location of the eight-thousanders

In 1978, he made a solo ascent of the Diamir face of Nanga Parbat. In 1986, Messner became the first to complete all fourteen eight-thousanders (peaks over 8,000 metres above sea level).

Messner has crossed Antarctica on skis, together with fellow explorer Arved Fuchs.[citation needed]

He has written over 80 books[13] about his experiences, a quarter of which have been translated. He was featured in the 1984 film The Dark Glow of the Mountains by Werner Herzog.

From 1999 to 2004, he held political office as a Member of the European Parliament for the Italian Green Party (Federazione dei Verdi). He was also among the founders of Mountain Wilderness, an international NGO dedicated to the protection of mountains worldwide.[citation needed]

In 2004 he completed a 2,000-kilometre (1,200 mi) expedition through the Gobi desert.[citation needed]

In 2006, he founded the Messner Mountain Museum.

Expeditions[edit]

Ascents above 8,000m[edit]

Messner was the first person to climb all fourteen eight-thousanders in the world and without supplemental oxygen. His climbs were also all amongst the first 20 ascents for each mountain individually. Specifically, these are:

| Year | Peak | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Nanga Parbat (8,125 m or 26,657 feet) | First ascent of the unclimbed Rupal Face and first traverse of the mountain by descending along the unexplored Diamir Face with his brother Günther. |

| 1972 | Manaslu (8,163 m or 26,781 feet) | First ascent of the unclimbed South-West Face[14] and first ascent of Manaslu without supplemental oxygen.[15] |

| 1975 | Gasherbrum I (8,080 m or 26,510 feet) | First ascent without supplemental oxygen with Peter Habeler.[15] |

| 1978 | Mount Everest (8,848 m or 29,029 feet), Nanga Parbat (8,125 m or 26,657 feet) | First ascent of Everest without supplementary oxygen (with Peter Habeler).[15][page needed] Nanga Parbat: first solo ascent of an eight-thousander from base camp. He established a new route on the Diamir Face, which has since then never been repeated.[16][page needed] |

| 1979 | K2 (8,611 m or 28,251 feet) | Ascent partially in alpine style with Michael Dacher on the Abruzzi Spur. |

| 1980 | Mount Everest (8,848 m or 29,029 feet) | First to ascend alone and without supplementary oxygen – from base camp to summit – during the monsoon. He established a new route on the North Face. |

| 1981 | Shishapangma (8,027 m or 26,335 feet) | Ascent with Friedl Mutschlechner. |

| 1982 | Kangchenjunga (8,586 m or 28,169 feet), Gasherbrum II (8,034 m or 26,358 feet), Broad Peak (8,051 m or 26,414 feet) | New route on Kangchenjunga’s North Face, partially in alpine style with Friedl Mutschlechner. Gasherbrum II and Broad Peak: Both ascents with Sher Khan and Nazir Sabir. Messner becomes the first person to climb three 8000er in one season. Also a failed summit attempt on Cho Oyu during winter. |

| 1983 | Cho Oyu (8,188 m or 26,864 feet) | Ascent with Hans Kammerlander and Michael Dacher on a partially new route. |

| 1984 | Gasherbrum I (8,080 m or 26,510 feet), Gasherbrum II (8,034 m or 26,358 feet) | First traverse of two eight-thousanders without returning to base camp (with Hans Kammerlander). |

| 1985 | Annapurna (8,091 m or 26,545 feet), Dhaulagiri (8,167 m or 26,795 feet) | First ascent of Annapurna’s unclimbed North-West Face. Both ascents with Hans Kammerlander. |

| 1986 | Makalu (8,485 m or 27,838 feet), Lhotse (8,516 m or 27,940 feet) | Makalu: Ascent with Hans Kammerlander and Friedl Mutschlechner, Lhotse: Ascent with Hans Kammerlander. Messner becomes the first person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders. |

Other expeditions since 1970[edit]

Reinhold Messner in 1985 in Pamir Mountains.

- 1971 – Journeys to the mountains of Persia, Nepal, New Guinea, Pakistan and East Africa;

- 1972 – Noshak (7,492 m or 24,580 feet) in the Hindu Kush;

- 1973 – Marmolada West Pillar, first climb; Furchetta West Face, first climb;

- 1974 – Aconcagua south wall (6,959 m or 22,831 feet), partially new «South Tyrol Route»; Eiger North Face with Peter Habeler in 10 hours (a record that stood for 34 years, for a roped party);

- 1976 – Mount McKinley (6,193 m or 20,318 feet), «Face of the Midnight Sun», first climb;

- 1978 – Kilimanjaro (5,895 m or 19,341 feet), «Breach Wall», first climb;

- 1979 – Ama Dablam rescue attempt; first climbs in the Hoggar Mountains, Africa;

- 1981 – Chamlang (7,317 m or 24,006 feet) Centre Summit-North Face, first climb;

- 1984 – Double-Traverse of Gasherbrum II and I with Hans Kammerlander;

- 1985 – Tibet Transversale with Kailash exploration;

- 1986 – Crossing of East Tibet; Mount Vinson (4,897 m or 16,066 feet, Antarctic), on 3 December 1986, thus becoming the first person to complete Seven Summits without the use of supplemental oxygen on Mount Everest;[17]

- 1987 – Bhutan trip; Pamir trip;

- 1988 – Yeti-Tibet solo expedition;

- 1989–1990 – Antarctic crossing (over the South Pole) on foot, 2,800-kilometre (1,700-mile) trek with Arved Fuchs;

- 1991 – Bhutan crossing (east-west); «Around South Tyrol» as a positioning exercise, where he was peripherally involved in the Ötzi find, being among the groups who inspected the mummy on-site the day after its initial discovery;

- 1992 – Ascent of Chimborazo (6,310 m or 20,700 feet); crossing of Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang;

- 1993 – Trip to Dolpo, Mustang and Manang in Nepal; Greenland longitudinal crossing (diagonal) on foot, 2,200-kilometre (1,400-mile) trek;

- 1994 – Cleaning project in North India/Gangotri, Shivling region (6,543 m or 21,467 feet); to Ruwenzori (5,119 m or 16,795 feet), Uganda;

- 1995 – Arctic crossing (Siberia to Canada) failed; trip to Belukha (4,506 m or 14,783 feet), Altai Mountains/Siberia;

- 1996 – Trip through East Tibet and to Kailash.

- 1997 – Trip to Kham (East Tibet); small expedition into Karakoram; filming on the Ol Doinyo Lengai (holy mountain of the Maasai) in Tanzania

- 1998 – Trip to the Altai Mountains (Mongolia) and to Puna de Atacama (Andes)

- 1999 – Filming: San Francisco Peaks, Arizona (Holy mountain of Navajo); trip into the Thar Desert/India

- 2000 – Crossing of South Georgia on the Shackleton Route; Nanga Parbat Expedition; filming on Mount Fuji/Japan for the ZDF series Wohnungen der Götter (~»Homes of the Gods»)

- 2001 – Dharamsala and foothills of the Himalayas/India; ZDF series Wohnungen der Götter on Gunung Agung/Bali

- 2002 – In the «International Year of the Mountains» visit by mountaineers into the Andes and ascent of Cotopaxi (5,897 m or 19,347 feet), Ecuador

- 2003 – Trekking to Mount Everest (fiftieth anniversary of the first successful climb); trip to Franz Joseph Land/Arctic; on 1 October opening of the «Günther Mountain School» in the Diamir Valley on Nanga Parbat/Pakistan

- 2004 – Longitudinal crossing of the Gobi Desert (Mongolia) on foot, about 2,000-kilometre (1,200-mile) trek

- 2005 – Trip to the Dyva Nomads in Mongolia; «time journey» around Nanga Parbat/Pakistan

Climbs[edit]

Nanga Parbat[edit]

Reinhold Messner took a total of five expeditions to Nanga Parbat. In 1970 and 1978 he reached the summit (in 1978 solo); in 1971, 1973 and 1977, he did not. In 1971 he was primarily looking for his brother’s remains.

Rupal Face 1970[edit]

In May and June 1970, Messner took part in the Nanga Parbat South Face expedition led by Karl Herrligkoffer, the objective of which was to climb the as yet unclimbed Rupal Face, the highest rock and ice face in the world. Messner’s brother, Günther, was also a member of the team. On the morning of 27 June, Messner was of the view that the weather would deteriorate rapidly, and set off alone from the last high-altitude camp. Surprisingly his brother climbed after him and caught up to him before the summit. By late afternoon, both had reached the summit of the mountain and had to pitch an emergency bivouac shelter without tent, sleeping bags and stoves because darkness was closing in.[citation needed]

The events that followed have been the subject of years of legal actions and disputes between former expedition members, and have still not been finally resolved. What is known now is that Reinhold and Günther Messner descended the Diamir Face, thereby achieving the first traverse of Nanga Parbat and second traverse of an eight-thousander after Mount Everest in 1963. Reinhold arrived in the valley six days later with severe frostbite, but survived. His brother, Günther, however died on the Diamir Face—according to Reinhold Messner on the same descent, during which they became further and further separated from each other. As a result, the time, place and exact cause of death is unknown. Messner said his brother had been swept away by an avalanche.[citation needed]

In the early years immediately after the expedition, there were disputes and lawsuits between Messner and Herrligkoffer, the expedition leader. After a quarter-century of peace, the dispute flared up again in October 2001, when Messner raised surprising allegations against the other members of the team for failing to come to their aid. The rest of the team consistently maintained that Messner had told them of his idea for traversing the mountain before setting off for the summit. Messner himself asserts, however, that he made a spontaneous decision to descend the Diamir Face together with his brother for reasons of safety. A number of new books—by Max von Kienlin, Hans Saler, Ralf-Peter Märtin, and Reinhold Messner—stoked the dispute (with assumptions and personal attacks) and led to further court proceedings.[citation needed]

In June 2005, after an unusual heat wave on the mountain, the body of his brother was recovered on the Diamir Face, which seems to support Messner’s account of how Günther died.[18][19]

The drama was turned into a film Nanga Parbat (2010) by Joseph Vilsmaier, based on the memories of Reinhold Messner and without participation from the other former members of the expedition. Released in January 2010 in cinemas, the film was criticised by the other members of the team for telling only one side of the story.[19]

Because of severe frostbite, especially on his feet—seven toes were amputated—Messner was not able to climb quite as well on rock after the 1970 expedition. He therefore turned his attention to higher mountains, where there was much more ice.[20]

Solo climb in 1978[edit]

On 9 August 1978, after three unsuccessful expeditions, Messner reached the summit of Nanga Parbat again via the Diamir Face.[citation needed]

Manaslu[edit]

In 1972, Messner succeeded in climbing Manaslu on what was then the unknown south face of the mountain, of which there were not even any pictures. From the last high-altitude camp he climbed with Frank Jäger, who turned back before reaching the summit. Shortly after Messner reached the summit, the weather changed and heavy fog and snow descended. Initially Messner became lost on the way down, but later, heading into the storm, found his way back to the camp, where Horst Fankhauser and Andi Schlick were waiting for him and Jäger. Jäger did not return, although his cries were heard from the camp. Orientation had become too difficult. Fankhauser and Schlick began to search for him that evening, but lost their way and sought shelter at first in a snow cave. Messner himself was no longer in a position to help the search. The following day, only Horst Fankhauser returned. Andi Schlick had left the snow cave during the night and disappeared. So the expedition had to mourn the loss of two climbers. Messner was later criticised for having allowed Jäger go back down the mountain alone.[20]

Gasherbrum I[edit]

Together with Peter Habeler, Messner made a second ascent of Gasherbrum I on 10 August 1975, becoming the first man ever to climb more than two eight-thousanders. It was the first time a mountaineering expedition succeeded in scaling an eight-thousander using alpine style climbing.[citation needed] Until that point, all fourteen 8000-meter peaks had been summitted using the expedition style, though Hermann Buhl had earlier advocated «West Alpine Style» (similar to «capsule» style, with a smaller group relying on minimal fixed ropes).[citation needed]

Messner reached the summit again in 1984, this time together with Hans Kammerlander. This was achieved as part of a double ascent where, for the first time, two eight-thousander peaks (Gasherbrum I and II) were climbed without returning to base camp. Again, this was done in alpine style, i.e. without the pre-location of stores.[20] Filmmaker Werner Herzog accompanied the climbers along the 150-kilometre (93 mi) approach to base camp, interviewing them extensively about why they were making the climb, if they could say; they could not. Messner became emotional on camera when he recalled having to tell his mother about his brother’s death.

It took a week for the two climbers to summit both peaks and return to camp, after which Herzog interviewed them again. His documentary, The Dark Glow of the Mountains, with some footage the two climbers shot during the expedition on portable cameras, was released the following year.

Mount Everest[edit]

On 8 May 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler reached the summit of Mount Everest, becoming the first men known to climb it without the use of supplemental oxygen. Before this ascent, it was disputed whether this was possible at all. Messner and Habeler were members of an expedition led by Wolfgang Nairz along the southeast ridge to the summit. Also on this expedition was Reinhard Karl, the first German to reach the summit, albeit with the aid of supplemental oxygen.[citation needed]

Two years later, on 20 August 1980, Messner again stood atop the highest mountain in the world, without supplementary oxygen. For this solo climb, he chose the northeast ridge to the summit, where he crossed above the North Col in the North Face to the Norton Couloir and became the first man to climb through this steep gorge to the summit. Messner decided spontaneously during the ascent to use this route to bypass the exposed northeast ridge. Before this solo ascent, he had not set up a camp on the mountain.[20][page needed] When he returned he was nearly dead and the medical team who met him at the bottom of the mountain asked him, «why would you go up there to die?» and Messner replied, «I went up there to live.»[21]

K2[edit]

For 1979, Messner was planning to climb K2 on a new direct route through the South Face, which he called the «Magic Line». Headed by Messner, the small expedition consisted of six climbers: Italians Alessandro Gogna, Friedl Mutschlechner and Renato Casarotto; the Austrian, Robert Schauer; and Germans Michael Dacher, journalist, Jochen Hölzgen, and doctor Ursula Grether, who was injured during the approach and had to be carried to Askole by Messner and Mutschlechner. Because of avalanche danger on the original route and time lost on the approach, they decided to climb via the Abruzzi Spur. The route was equipped with fixed ropes and high-altitude camps, but no hauling equipment (Hochträger) or bottled oxygen was used. On 12 July, Messner and Dacher reached the summit; then the weather deteriorated and attempts by other members of the party failed.[22][23]

Shishapangma[edit]

During his stay in Tibet as part of his Everest solo attempt, Messner explored Shishapangma. A year later, Messner, with Friedel Mutschlechner, Oswald Oelz, and Gerd Baur, set up a base camp on the north side. On 28 May, Messner and Mutschlechner reached the summit in very bad weather; part of the climb involving ski mountaineering.[20][23]

Kangchenjunga[edit]

In 1982, Messner wanted to become the first climber ever to scale three eight-thousanders in one year. He was planning to climb Kangchenjunga, then Gasherbrum II and the Broad Peak.[citation needed]

Messner chose a new variation of the route up the north face. Because there was still a lot of snow, Messner and Mutschlechner made very slow progress. In addition, the difficulty of the climb forced the two mountaineers to use fixed ropes. Finally, on 6 May, Messner and Mutschlechner stood on the summit. There, Mutschlechner suffered frostbite to his hands, and later to his feet as well. While bivouacking during the descent, the tent tore away from Mutschlechner and Messner, and Messner also fell ill. He was suffering from amoebic liver abscess, making him very weak. He made it back to base camp only with Mutschlechner’s help.[20]

Gasherbrum II[edit]

After his ascent of Kangchenjunga, Mutschlechner flew back to Europe because his frostbite had to be treated and Messner needed rest. Thus the three mountains could not be climbed as planned. Messner was cured of his amoebic liver abscess and then travelled to Gasherbrum II, but could not use the new routes as planned. In any case, his climbing partners, Sher Khan and Nazir Sabir, would not have been strong enough. Nevertheless, all three reached the summit on 24 July in a storm. During the ascent, Messner discovered the body of a previously missing Austrian mountaineer, whom he buried two years later at the G I – G II traverse.[20]

Broad Peak[edit]

In 1982, Messner scaled Broad Peak, his third eight-thousander. At the time, he was the only person with a permit to climb this mountain; he came across Jerzy Kukuczka and Wojciech Kurtyka, who had permits to climb K2, but used its geographic proximity to climb Broad Peak illegally. In early descriptions of the ascent, Messner omitted this encounter, but he referred to it several years later. On 2 August, Messner was reunited with Nazir Sabir and Khan again on the summit. The three mountaineers had decamped and made for Broad Peak immediately after their ascent of Gasherbrum II. The climb was carried out with a variation from the normal route at the start.[20]

Cho Oyu[edit]

In the winter of 1982–83, Messner attempted the first winter ascent of Cho Oyu. He reached an altitude of about 7,500 m (24,600 feet), when great masses of snow forced him to turn back. This expedition was his first with Hans Kammerlander. A few months later, on 5 May, he reached the summit via a partially new route together with Kammerlander and Michael Dacher.[20]

Annapurna[edit]

In 1985, Messner topped out on Annapurna. Using a new route on the northwest face, he reached the summit with Kammerlander on 24 April. Also on the expedition were Reinhard Patscheider, Reinhard Schiestl and Swami Prem Darshano, who did not reach the summit. During Messner and Kammerlander’s ascent, the weather was bad and they had to be assisted by the other three expedition members during the descent due to heavy snowfall.[20]

Dhaulagiri[edit]

Messner’s attempt on the summit in 1977 failed on Dhaulagiri’s South Face.

Messner had already attempted Dhaulagiri in 1977 and 1984, unsuccessfully. In 1985 he finally summited. He climbed with Kammerlander up the normal route along the northeast ridge. After only three days of climbing they stood on the summit in a heavy storm on 15 May.[20]

Makalu[edit]

Messner tried climbing Makalu four times. He failed in 1974 and 1981 on the South Face of the south-east ridge. In winter 1985–1986 he attempted the first winter ascent of Makalu via the normal route. Even this venture did not succeed.[20] Not until February 2009 was Makalu successfully climbed in winter by Denis Urubko and Simone Moro.

In 1986, Messner returned and succeeded in reaching the summit using the normal route with Kammerlander and Mutschlechner. Although they had turned back twice during this expedition, they made the summit on the third attempt on 26 September. During this expedition, Messner witnessed the death of Marcel Rüedi, for whom the Makalu was his 9th eight-thousander. Rüedi was on the way back from the summit and was seen by Messner and the other climbers on the descent. Although he was making slow progress, he appeared to be safe. The tea for his reception had already been boiled when Rüedi disappeared behind a snow ridge and did not reappear. He was found dead a short time later.[20]

Lhotse[edit]

Messner climbed his last normal route.[when?] Messner and Kammerlander had to contend with a strong wind in the summit area. To reach the summit that year and before winter broke, they took a direct helicopter flight from the Makalu base camp to the Lhotse base camp.[citation needed]

Thus Messner became the first person to climb all eight-thousanders.

Since this ascent, Messner has never climbed another eight-thousander.[20]

In 1989, Messner led a European expedition to the South Face of the mountain. The aim was to forge a path up the as-yet-unclimbed face. Messner himself did not want to climb any more. The expedition was unsuccessful.[24]

The Seven Summits[edit]

In 1985 Richard Bass first postulated and achieved the mountaineering challenge Seven Summits, climbing the highest peaks of each of the seven continents. Messner suggested another list (the Messner or Carstensz list) replacing Mount Kosciuszko with Indonesia’s Puncak Jaya, or Carstensz Pyramid (4,884 m or 16,024 feet). From a mountaineering point of view the Messner list is the more challenging one. Climbing Carstensz Pyramid has the character of an expedition, whereas the ascent of Kosciuszko is an easy hike. In May 1986 Pat Morrow became the first person to complete the Messner list, followed by Messner himself when he climbed Mount Vinson in December 1986 to become the second.[17]

World-first records[edit]

Messner is listed nine times in the Guinness Book of Records. All of his achievements are classed as «World’s Firsts» (or «Historical Firsts»). A «World’s First» is the highest category of any Guinness World Record, meaning the ownership of the title never expires.[25] As of 2021, Messner is the second highest record holder of «World’s Firsts» (after Icelandic explorer Fiann Paul, who has 13). Messner’s world firsts are:

- First ascent of Manaslu without supplementary oxygen

- First solo summit of Everest

- First ascent of Everest and K2 without supplementary oxygen – male

- First ascent of the top three highest mountains without supplementary oxygen – male

- First 8,000-metre mountain hat-trick

- First person to climb all 8,000-metre mountains without supplementary oxygen

- First person to climb all 8,000-metre mountains

- First ascent of Everest without supplementary oxygen

- First ascent of Gasherbrum I without supplementary oxygen

Messner Mountain Museum[edit]

Messner Mountain Museum in Monte Rite, Dolomites.

In 2003 Messner started work on a project for a mountaineering museum.[26] On 11 June 2006, the Messner Mountain Museum (MMM) opened, a museum that unites within one museum the stories of the growth and decline of mountains, culture in the Himalayan region and the history of South Tyrol.

The MMM consists of five or six locations:

- MMM Firmian at Sigmundskron Castle near Bozen is the centerpiece of the museum and concentrates on man’s relationship with the mountains. Surrounded by peaks from the Schlern and the Texel range, the MMM Firmian provides visitors with a series of pathways, stairways, and towers containing displays that focus on the geology of the mountains, the religious significance of mountains in the lives of people, and the history of mountaineering and alpine tourism. The so-called white tower is dedicated to the history of the village and the struggle for the independence of South Tyrol.[27]

- MMM Juval at Juval Castle in the Burggrafenamt in Vinschgau is dedicated to the «magic of the mountains», with an emphasis on mystical mountains, such as Mount Kailash or Ayers Rock and their religious significance. MMM Juval houses several art collections.[28]

- MMM Dolomites, known as the Museum in the Clouds, is located at Monte Rite (2,181 m or 7,156 feet) between Pieve di Cadore and Cortina d’Ampezzo. Housed in an old fort, this museum is dedicated to the subject of rocks, particularly in the Dolomites, with exhibits focusing on the history of the formation of the Dolomites. The summit observation platform offers a 360° panorama of the surrounding Dolomites, with views toward Monte Schiara, Monte Agnèr, Monte Civetta, Marmolada, Monte Pelmo, Tofana di Rozes, Sorapis, Antelao, Marmarole.[29]

- MMM Ortles at Sulden on the Ortler is dedicated to the theme of ice. This underground structure is situated at 1,900 m (6,200 feet) and focuses on the history of mountaineering on ice and the great glaciers of the world. The museum contains the world’s largest collection of paintings of the Ortler, as well as ice-climbing gear from two centuries.[30]

- MMM Ripa at Brunico Castle in South Tyrol is dedicated to the mountain peoples from Asia, Africa, South America and Europe, with emphasis on their cultures, religions, and tourism activities.[31]

- MMM Corones, opened in July 2015 on the top of the Kronplatz mountain (Plan de Corones in Italian), is dedicated to traditional climbing.[32]

Political career[edit]

In 1999, Messner was elected Member of the European Parliament for the Federation of the Greens (FdV), the Italian green party, receiving more than 20,000 votes in the European election. He fully served his term until 2004, when he retired from politics.[33]

Messner was officially a member of South Tyrolean Greens, a regionalist and ecologist political party active only in South Tyrol, which de facto acts as a regional branch of the FdV.

During all his life, even after the end of his political career, he has been a strong supporter of green and environmentalist policies and an activist in the fight against global warming.[citation needed]

Electoral history[edit]

Personal life[edit]

From 1972 until 1977, Messner was married to Uschi Demeter. With his partner, Canadian photographer Nena Holguin, he has a daughter, Làyla Messner, born in 1981.[34] On 31 July 2009, he married his long time girlfriend Sabine Stehle, a textile designer from Vienna, with whom he has 3 children.[35]

They divorced in 2019.[36] In late May 2021, Messner married Diane Schumacher, a 41-year-old Luxembourg woman living in Munich,[37][38] at the town hall in Kastelbell-Tschars near his home in South Tyrol.[39][40]

In media[edit]

- The Dark Glow of the Mountains (Gasherbrum – Der Leuchtende Berg), a 1985 Werner Herzog television documentary

- Portrait of a Snow Lion, a BBC/France3 1992 documentary on Messner; part 4 of the series The Climbers[41]

- Messner, a 2002 feature documentary about Messner by Les Guthman[42]

- Lissi und der wilde Kaiser, an animated comedy movie from 2007 by Michael Herbig ends with a photo of the Yeti with his new buddy, Reinhold Messner.

- Nanga Parbat, a 2010 film based on Messner’s achievements

- The Unauthorized Biography of Reinhold Messner, a 1999 album by Ben Folds Five, unrelated to Messner

- 14 Peaks: Nothing Is Impossible, a 2021 Netflix documentary film about Nirmal Purja and his mountaineering team’s world record breaking ascent of the 14 highest mountains in the world. Reinhold Messner provides commentary in several interview segments. The New York Times described his contribution to the film as «the alpine legend Reinhold Messner waxing beautifully existential».[43]

See also[edit]

- List of climbers

References[edit]

- ^ Messner, Reinhold (1991). Antarctica: Both Heaven and Hell. ISBN 9780898863055.

- ^ Messner, Reinhold (2013). Gobi: Il deserto dentro di me (in Italian). ISBN 9788897173236.

- ^ Kratzer, Clemens (2012). «Messner – der Film». Alpin – das BergMagazin. 9: 9. ISSN 0177-3542.

- ^ Lisa Stocker (9 April 2009). «Waltraud Kastlunger und ihre Brüder». BRIGITTE-woman.de.

- ^ a b Alexander, Caroline (November 2006). «Murdering the Impossible». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006.

- ^ Messner, Reinhold (1979). Aufbruch ins Abenteuer. Der berühmteste Alpinist der Welt erzählt (in German). Bergisch Gladbach: Bastei Lübbe. pp. 122–133.

- ^ «Die Füße des Extrembergsteigers». Stern (in German). 3 November 2006.

- ^ Rhoads, Christopher (11 December 2003). «The controversy surrounding Reinhold Messner». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (19 January 2010). «Nanga Parbat film restarts row over Messner brothers’ fatal climb». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ «Reinhold Messner — Bücher». Reinhold-messner.de. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Nairsz, Wolfgang (1974). «Manaslu 1972» (PDF). alpinejournal.org.uk.

- ^ a b c «General Info». 8000ers.com.

- ^ Moro, Simone (2016). Nanga: Fra rispetto e pazienza, come ho corteggiato la montagna che chiamavano assassina (in Italian). ISBN 9788817090230.

- ^ a b History of 7 Summits project – who was first?

- ^ «Nanga Parbat Body Ends Messner Controversy». Outdoors Magic. 19 August 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b Connolly, Kate (19 January 2010). «Nanga Parbat film restarts row over Messner brothers’ fatal climb». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Messner, Reinhold (2002). Überlebt – Alle 14 Achttausender mit Chronik (in German). Munich: BLV.

- ^ Jurassic Park Script

- ^ Messner, Reinhold; Gogna, Alessandro (1980). K2 – Berg der Berge (in German). Munich: BLV.

- ^ a b Messner, Reinhold (1983). Alle meine Gipfel (in German). Munich: Herbig.

- ^ Kammerlander, Hans (2001). Bergsüchtig (in German) (6 ed.). Munich: Piper. p. 81ff.

- ^ «Official Guinness Registry». Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ Kunze, Thomas (8 July 2006). «Messners 15. Achttausender». Berliner Zeitung. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011.

- ^ «MMM Firmian». Messner Mountain Museum. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ «MMM Juval». Messner Mountain Museum. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ «MMM Dolomites». Messner Mountain Museum. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ «MMM Ortles». Messner Mountain Museum. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ «MMM Ripa». Messner Mountain Museum. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ Federica Lusiardi. «Zaha Hadid’s MMM Corones museum gazes at the mountains». Inexhibit. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ «Search for a Member; European Parliament». Europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ «Nena Holguin». Wiki Data. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ «Reinhold Messner trickste Neugierige aus: Einen Tag früher geheiratet». OÖNachrichten. OÖ. Online GmbH & Co.KG. 1 August 2009.

- ^ Messner sagt Ja, tageszeitung.it, 11 May 2021

- ^ Who is Diane Schumacher, the future wife of Reinhold Messner, tipsforwomens.org, 12 May 2021

- ^ Reden wir über Liebe, tageszeitung.it, 29 May 2021 (in German)

- ^ Unter der Haube, tageszeitung.it, 29 May 2021

- ^ Reinhold Messner erneut verheiratet, orf.at, 29. Mai 2021 (in German)

- ^ «Portrait of a snow lion». MNTNFILM. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ «Messner». MNTNFILM. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Kennedy, Lisa (1 December 2021). «’14 Peaks: Nothing Is Impossible’ Review: Climbing at a Breakneck Pace». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

Selected bibliography (English translations)[edit]

- The Crystal Horizon: Everest – The First Solo Ascent. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. 1989. ISBN 978-0-89886-574-5.

- Free Spirit: A Climber’s Life. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. 1998. ISBN 978-0-89886-573-8.

- All Fourteen 8,000ers. Mountaineers Books. 1999. ISBN 978-0-89886-660-5.

- My Quest for the Yeti: Confronting the Himalayas’ Deepest Mystery. New York: St. Martin’s Press. 2000. ISBN 978-0-312-20394-8.

- The Big Walls: From the North Face of the Eiger to the South Face of Dhaulagiri. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. 2001. ISBN 978-0-89886-844-9.

- Moving Mountains: Lessons on Life and Leadership. Provo: Executive Excellence. 2001. ISBN 978-1-890009-90-8.

- The Second Death of George Mallory: The Enigma and Spirit of Mount Everest. Translated by Carruthers, Tim. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. 2002. ISBN 978-0-312-27075-9.

- The Naked Mountain. Seattle, WA, USA: Mountaineers Books. 2003. ISBN 978-0-89886-959-0.

- My Life at the Limit. Seattle, WA, USA: Mountaineers Books. 2014. ISBN 978-1-59485-852-9.

Sources[edit]

- Wetzler, Brad (October 2002). «Reinhold Don’t Care What You Think». Outside Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010.

- Krakauer, Jon (1997). Into Thin Air. New York: Villard Books. ISBN 978-0385494786. OCLC 42967338.

Further reading[edit]

- Messner, Reinhold (October 1981). «I Climbed Everest Alone… At My Limit». National Geographic. Vol. 160, no. 4. pp. 552–566. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links[edit]

- Official site (in German)

- Discovery of remains ends controversy about the death of Reinhold Messner’s brother

- (rare English interview with Messner) on YouTube

- [1] Reinhold Messner on the Future of Climbing Mount Everest — an interview with Saransh Sehgal

Interviews[edit]

- Gaia Symphony Documentary series (Japanese production).

- Reinhold Messner Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement.

Цена: 997,50 руб.

английский

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

китайский

русский

Синонимы

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

китайский

украинский

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

альпинист Рейнхольд Месснер

Very famous, very accomplished Italian mountaineer, Reinhold Messner, tried it in 1995, and he was rescued after a week.

Very famous, very accomplished Italian mountaineer, Reinhold Messner, tried it in 1995,

Другие результаты

Reinhold Messner is the strongest climber today.

Рейнхольд Месснер является сильнейшим альпинистом на сегодняшний день.

And Reinhold Messner should be the first to climb to the top.

Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler of the Austrian expedition yesterday climbed Everest without oxygen.

Рейнхольд Месснер и Питер Хабелер из австрийской экспедиции поднялись вчера на Эверест без использования кислорода.

Reinhold Messner top never let go.

Austria’s Reinhold Messner becomes the first man to climb Everest alone and without oxygen equipment.

Райнхольд Месснер первым поднимается на Эверест в одиночку и без кислородного аппарата.

1978 — The first ascent of Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen, by Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler.

1978 — Первое восхождение на Джомолунгму без кислородных приборов Питера Хабелера и Райнхольда Месснера.

I can not judge how sore upon wine… sore upon wine Reinhold Messner.

«The most beautiful mountains in the world» Reinhold Messner — Dolomites

The celebrated Reinhold Messner had to pull out twice here, in 1977 and 1984, and only succeeded in 1985 at a third try.

Дважды — в 77-м и 84-м — здесь отступал знаменитый Райнхольд Месснер и добился успеха только с третьей попытки в 1985- м…

1983 Reinhold Messner succeeds on his fourth attempt, with Hans Kammerlander and Michael Dacher.

1983 — Райнхольд Месснер с четвёртой попытки покорил Чо-Ойю в связке с Хансом Каммерлендером и Михелем Дахером.

The first person to climb all 14 eight-thousanders was the Italian Reinhold Messner, on 16 October 1986.

Первым человеком, покорившим все 14 восьмитысячников планеты, стал в 1986 году итальянец Райнхольд Месснер.

Vladislav Terzyul (1953-2004) — a climber who climbed all 14 mountains higher than Earth’s 8000 meters, repeating the record of Reinhold Messner.

Владислав Терзыул (1953-2004) — альпинист, который покорил все 14 гор Земли высотой более 8 тысяч метров, повторив рекорд Рейнхольда Месснера.

On 8 May 1978, Reinhold Messner (Italy) and Peter Habeler (Austria) reached the summit, the first climbers to do so without the use of supplemental oxygen.

8 мая 1978 года итальянец Райнхольд Месснер и австриец Петер Хабелер (англ. Peter Habeler) совершили первое восхождение на вершину Джомолунгмы без использования кислородных приборов.

On December 30, 1989, Arved Fuchs and Reinhold Messner were the first to traverse Antarctica via the South Pole without animal or motorized help, using only skis and the help of wind.

30 декабря 1989 года Южного полюса достигли Арвид Фукс и Рейнольд Мейснер, которые пересекли Антарктиду без использования собак или механического транспорта — им помогала только мускульная сила и иногда паруса.

Результатов: 16. Точных совпадений: 2. Затраченное время: 64 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Watch Free Movies Online: http://bit.ly/snag_films

Like Us On Facebook: http://bit.ly/snag_fb

Follow Us On Twitter: http://bit.ly/Snag_Tweets

Synopsis:

Reinhold Messner, the world’s greatest mountain climber, looks back over his career with surprising candor and self-revelation. It is the career of a man who began climbing with his father in the exquisite Italian Dolomites, but whose restless quest for self-knowledge through extreme adventures made him the most accomplished climber of modern times. MESSNER includes rare film of his astonishing climbs of the world’s highest mountains — without using bottled oxygen and often alone.

About SnagFilms:

Watch free movies on SnagFilms. From award-winning independent films to groundbreaking documentaries, we’ve got you covered. Our rapidly expanding library of more than 9,000 titles will transport you to new cinematic worlds. With one of the largest collections of independent films, we’ve collected all the best movies in one place — must-see documentaries, iconic Hollywood films, cult classics, huge stars before they were famous, National Geographic specials, foreign flicks, award-winning shorts, Sundance selections and Oscar favorites. Looking for action, comedy, horror, or drama? We’ve got it all. All our films are hand-curated by our editorial staff of film lovers and filmmakers to ensure that each time you visit SnagFilms, you are sure to Discover Something Different.

For faster navigation, this Iframe is preloading the Wikiwand page for Reinhold Messner.

1) Установите соответствие между заголовками 1 — 8 и текстами A — G. Используйте каждую цифру только один раз. В задании один заголовок лишний.

1. Music from every corner of the world

2. From pig to pork

3. Perfect time for a picnic

4. From a holiday to a sport

5. Famous religious celebrations

6. See them fly

7. Animal races and shows

8. Diving into history

A. Diwali is a five-day festival that is celebrated in October or November, depending on the cycle of the moon. It represents the start of the Hindu New Year and honors the victory of good over evil, and brightness over darkness. It also marks the start of winter. Diwali is actually celebrated in honor of Lord Rama and his wife Sita. One of the best places to experience Diwali is in the «pink city» of Jaipur, in Rajasthan. Each year there’s a competition for the best decorated and most brilliantly lit up market that attracts visitors from all over India.

B. The Blossom Kite Festival, previously named the Smithsonian Kite Festival, is an annual event that is traditionally a part of the festivities at the National Cherry Blossom Festival on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Kite enthusiasts show off their stunt skills and compete for awards in over 36 categories including aerodynamics and beauty. The Kite Festival is one of the most popular annual events in Washington, DC and features kite fliers from across the U.S. and the world.

C. The annual Ostrich Festival has been recognized as one of the «Top 10 Unique Festivals in the United States» with its lanky ostriches, multiple entertainment bands and many special gift and food vendors. It is truly a unique festival, and suitable for the entire family. The Festival usually holds Ostrich Races, an Exotic Zoo, Pig Races, a Sea Lion Show, a Hot Rod Show, Amateur Boxing and a Thrill Circus.

D. Iceland’s Viking Festival takes place in mid-June every year and lasts 6 days, no matter what the weather in Iceland may be. It’s one of the most popular annual events in Iceland where you can see Viking-style costumes, musical instruments, jewelry and crafts at the Viking Village. Visitors at the Viking Festival see sword fighting by professional Vikings and demonstrations of marksmanship with bows and muscle power. They can listen to Viking songs and lectures at the festival, or grab a bite at the Viking Restaurant nearby.

E. Dragon Boat Festival is one of the major holidays in Chinese culture. This summer festival was originally a time to ward off bad spirits, but now it is a celebration of the life of Qu Yuan, who was a Chinese poet of ancient period. Dragon boat festival has been an important holiday for centuries for Chinese culture, but in recent years dragon boat racing has become an international sport.

F. The Mangalica Festival is held in early February at Vajdahunyad Castle in Budapest. It offers the opportunity to experience Hungarian food, music, and other aspects of Hungarian culture. The festival is named for a furry pig indigenous to the region of Hungary and the Balkans. A mangalica is a breed of pig recognizable by its curly hair and known for its fatty flesh. Sausage, cheese and other dishes made with pork can be sampled at the festival.

G. Hanami is an important Japanese custom and is held all over Japan in spring. Hanami literally means «viewing flowers», but now it is a cherry blossom viewing. The origin of hanami dates back to more than one thousand years ago when aristocrats enjoyed looking at beautiful cherry blossoms and wrote poems. Nowadays, people in Japan have fun viewing cherry blossoms, drinking and eating. People bring home-cooked meals, do BBQ, or buy take-out food for hanami.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

2) Прочитайте текст и заполните пропуски A — F частями предложений, обозначенными цифрами 1 — 7. Одна из частей в списке 1—7 лишняя.

America’s fun place on America’s main street

If any city were considered a part of every citizen in the United States, it would be Washington, DC. To many, the Old Post Office Pavilion serves ___ (A). If you are in the area, be a part of it all by visiting us – or ___ (B). Doing so will keep you aware of the latest musical events, great happenings and international dining, to say the least.

Originally built in 1899, the Old Post Office Pavilion embodied the modern spirit ___ (C). Today, our architecture and spirit of innovation continues to evolve and thrive. And, thanks to forward-thinking people, you can now stroll through the Old Post Office Pavilion and experience both ___ (D) with international food, eclectic shopping and musical events. All designed to entertain lunch, mid-day and after work audiences all week long.

A highlight of the Old Post Office Pavilion is its 315-foot Clock Tower. Offering a breath-taking view of the city, National Park Service Rangers give free Clock Tower tours every day! Individuals and large tour groups are all welcome. The Old Post Office Clock Tower also proudly houses the official United States Bells of Congress, a gift from England ___ (E). The Washington Ringing Society sounds the Bells of Congress every Thursday evening and on special occasions.

Visit the Old Post Office Pavilion, right on Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and the Capitol. It is a great opportunity ___ (F), this is a landmark not to be missed no matter your age.

1. by joining our e-community

2. that are offered to the visitors

3. its glamorous past and fun-filled present

4. that was sweeping the country

5. to learn more about American history

6. as a landmark reminder of wonderful experiences

7. celebrating the end of the Revolutionary War

| A | B | C | D | E | F |

3) Прочитайте текст и запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Показать текст. ⇓

Speaking about her vegetarianism, the author admits that

1) it was provoked by the sight of corpses.

2) there were times when she thought she might abandon it.

3) it is the result of her childhood experiences.

4) she became a vegetarian out of fashion.

4) Прочитайте текст и запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Показать текст. ⇓

According to the author, how much of processed meat a day is enough to raise the chance of pancreatic cancer by more than a half?

1) Less than 50 g.

2) 50–100 g.

3) 100–150 g.

4) From 150 g.

5) Прочитайте текст и запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Показать текст. ⇓

“This” in paragraph 4 stands for

1) information.

2) pancreatic cancer.

3) diagnosis.

4) death.

6) Прочитайте текст и запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Показать текст. ⇓

Why does the author think that her information can’t be shocking?

1) It’s not proven.

2) It’s not news.

3) It’s outdated.

4) It’s too popular.

7) Прочитайте текст и запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Показать текст. ⇓

Saying “sympathy is in short supply these days”, the author means that

1) meat eaters do not deserve her sympathy.

2) overweight people should pay more.

3) people tend to blame sick people in their sickness.

4) society neglects people who have problems.

Показать текст. ⇓

The author is disappointed that eating meat is not

1) considered as bad as drinking and smoking.

2) officially prohibited.

3) related to a poor lifestyle.

4) recognized as a major life-risking habit.

9) Прочитайте текст и запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Показать текст. ⇓

The author believes that meat eaters are very

1) pessimistic.

2) ill-informed.

3) aggressive.

4) irresponsible.

There are so many firsts in your career. Why do you think you have been so successful doing things that others barely dared attempt?

So many people have died on Nanga Parbat and the other peaks you’ve climbed. Why do you think you survived?

When you were at the base of Mount Everest, preparing for the first solo ascent, what was going through your mind?

When you keep going higher and higher and you’re over 8,000 feet up, what’s it like to breathe in that thin air?

You’ve been called “the king of all climbers” and the most famous mountaineer in the world. What do you think makes you so remarkable?

Reinhold Messner: First of all, I’m not a king, and I would not like to be a king. I’m called “the king of the 8,000-meter” because I climbed them all and a few of them twice. I’m not a special person. I’m a normal person, but I had the opportunity in my life to make many experiences on the edge of the possibilities in the mountains — in Antarctica and Greenland, in the big deserts — and having this opportunity to go in the places where wilderness is still there. And I try to understand what’s happening with our nature. We have a nature in us — if we expose ourselves in the big nature, where it’s danger, where it’s loneliness, where it’s silence — and these feelings, for the normal people, they are gone. So many people are coming to see my museums, to listen to my lectures, to read my books because they hope to get something which they cannot get anymore. In the cities, they have no silence. The time is very, very cut. If I go to Antarctica, time is becoming endless. You know, midland in Antarctica, you have the feeling you are on a different star, on a different world, and time is not anymore existing. Time is only a measurement we invented.

What is it about pushing the limits that attracts you? Is it doing what nobody has ever done before?

Reinhold Messner: No, no, many people are doing this. This is a beautiful sport. Traditional mountaineering is not what’s happening in the gym, with indoor climbing walls. They are on artificial walls. It has nothing to do with traditional alpinism.

Alpinism has a tradition of 250 years, not more. Before we had the mythological time when people did not really go, and there were many stories about gods sitting on the mountains in the Greek philosophy. Also, in India, people have the feeling that Shiva is sitting on a high mountain, a holy mountain. In Tibet, they have holy mountains. This period is gone. Maybe somewhere in East Africa, with the Indios in South America, with the Sherpas in Nepal, with the Tibetans in Tibet, there is still a religious feeling between men — human beings — and the mountains.

But since 250 years, we have mountaineers, and this was beginning with scientists. They came especially from Britain, also from the European cities, to study the mountains. After the illumination (the Enlightenment) and with the beginning of the industrialization, people were open-minded enough, and they had the money to come to the Alps and conquer the Alps. In 1786, the Mont Blanc was conquered, and this is the birthday of traditional alpinism. And from this moment onwards, alpinism is evolving only in one direction: possible or impossible. That’s the question: possible or impossible? And each young generation tried to make possible what the old generation defined impossible.

In 1980, you climbed Mount Everest solo. That’s one of the greatest feats that a human being has ever accomplished. What preparation goes into an achievement like that?

Reinhold Messner: I had preparation for at least 30 years. My first steps, I did as a five-year-old boy in the Dolomites with my father and my mother and my older brother, climbing the first 3,000-meter peak, let’s say 10,000 feet — a climbing mountain but not a difficult one, an easy one. It’s the first step for the know-how I have today — also for the overview I have today. And in the first 15 years, I was climbing at home on smaller walls. But my capacity, my power, my agility, my knowledge was growing year by year, and I was doing always something more difficult. I tried to overcome the limit of yesterday, and next day, again overcome the limit of — my limit. There are two limits. There’s my limit, and this is changing. In young years, the limit is growing, growing, growing, and afterwards, up to a certain age, the limit is getting down. Today I can never again do what I did for 15 years.

Did you always know that you would be able to achieve what you have done?

Reinhold Messner: I could not know when I started that I could do it, but I knew 17 years past, so we have new equipment, we have a bigger knowledge because knowledge is growing with all alpinists together. We put our experiences together, our knowledge together. Also, if I don’t know certain alpinists, I get information from them, so knowledge is growing. Also now, I’m not putting in any knowledge anymore, but my son is today on a difficult wall in Switzerland, and he will put some new knowledge in because he’s one small part — millions of people are going to bring knowledge and know-how together for the next generations.

You’ve said that your son is out climbing today as we sit here. Don’t you worry about his safety?

Reinhold Messner: He’s not yet 30, he’s 27. But anyway, he’s mature. He’s doing his life. I was much more emotionally involved when he was 16, 17, when he was beginning to climb. He began very late, and he was not even so much into climbing because he had a few problems. It was the abyss and so on. Now he’s climbing on a very high level, but danger is there. But if I would steal him this possibility, as the father telling, “You should not do it,” I know exactly this is so dangerous. He could not do his life. When I was 16 — my brother was 14 — we were beginning to do extreme climbing, very young. And at three o’clock in the morning, we started at home. Our mother made us breakfast, and we put the rope and the pitons, and we went. And she never said, “Don’t do it. This is dangerous.”

Don’t you think that’s remarkable?

Reinhold Messner: That’s very remarkable because she was full of fear. But she also knew that if we would not do it, if we would be forced to leave this enthusiasm for climbing, we could never become strong characters. It’s not possible. You need the freedom to do what you like to do. And in this case, it’s very difficult for a mother, especially. In these circumstances, I have also to say that what we are doing is very egotistical, and we cannot take the responsibility in front of our parents, in front of our brothers, and so on. But if somebody is doing it, this is his fault or her fault, not mine.

Was there something in how you grew up or something your parents did that gave you this ambition to go beyond normal limits?

Reinhold Messner: No, not either, myself. I was only going in very small steps — every weekend, a little bit more higher, a little bit more difficult. And up to the age of 22, 23, 24, with the clear view, “I’m doing what the people of yesterday could not do.” In ‘68, I did my most difficult climb in the Dolomites, and for more than ten years, nobody could repeat it. So somebody thought it’s not possible to see past there, impossible that somebody pass there. And I was very proud because I said, “Okay, the climbs stopped on my limit now.” But after ten years, with new shoes, with better training, with new knowledge, people did it. And now this is a difficult passage, we call it, but it’s one of the passages.

George Mallory said he tried to climb Everest “because it’s there.” Why do you climb?

Reinhold Messner: This is an answer for one man for one mountain. Mallory went on Everest in ’21 and they did not either really try. But he was the key figure in this expedition. He found the route. He went up to 7,000 meters to the north wall and he could see this is possible. The ridge afterwards is possible. But he did not know if the summit ridge is possible, and he wrote in ’24 to his wife, before dying, “I will do it this time if, on the summit ridge, there is no vertical step which is stopping me,” which happened later on. Exactly this happened later.

Mallory went the second time on Everest in ’22 when they really were prepared to do the summit. And this British expedition was very focused on reaching the summit because Brits had to hide something. They tried many times on the north wall and failed. But the Brits were the leading conquerors of the world, not only for the colonies, but also for summits and so on. And they tried to go to the South Pole first. They tried many times. And on the end, a Norwegian man did it — Amundsen — and Scott came too late, one month too late.

Now the Brits changed Mount Everest from a mountain to “the third pole.” They called it, “This is the third pole,” to prove that they are able to reach first one pole. And in ’24, they tried a third time, and Mallory was in America before going to the third expedition, and a journalist asked him, “Why are you going the third time on Everest? You did it. You failed once. You failed the second time. Why do you go a third time?” And he answered, “Because it’s there.”

Some people say you are the greatest mountaineer of all time.

Reinhold Messner: No, no, no, no, no. There will be great mountaineers again.

But you’ve had enormous success.

Reinhold Messner: I had success. I did a lot of adventures. And especially, I did it in many fields. I was a rock climber. I was an alpine climber. I was an altitude climber. I did the traverse of Antarctica, a fact that we could not do. I crossed also Greenland a long way and then many, many things.

But not everything you tried succeeded.

Reinhold Messner: Right, I failed many times.

So when did you know it was time to turn back?

Reinhold Messner: One-third of my big adventures failed. Normally, I have a good feeling to see something is not functioning: the path is not good enough; the weather is not allowing; I am not in perfect shape, and so on.

Is it instinct again?

Reinhold Messner: It’s instinct, yeah. It’s more instinct. It’s not coming from pure knowledge or calculation. There’s no calculation.

You get a feeling?

Reinhold Messner: I get a feeling: “Now we are on the edge. We should go back in our situation.” I am not every day in the same shape over every year.

There was a decade when so many people had died on the 8,000-meter that people said the chances were high that you would die.

Reinhold Messner: And this was very interesting that 8,000-meter climbing was successful in the ‘50s and the beginning of the ‘60s. Then famous climbers went to the Himalayas with national expeditions paid by the nations, paid by the alpine clubs, and they did the first ascents. And all the nations where they had climbers tried to do the 8,000-meter peaks.

So the first ones were French people. And the French people, after the Second World War, were the leading climbers worldwide. So they did also the first 8,000-meter peak. The second 8,000-meter peak was done by the British (English) — and the English, they had the biggest experience. And they were forced to do it because the Swiss people tried it; they went very high. So they got a permit, and they knew, “This time we have to do it, otherwise we lose our reputation.” The next one was an Austrian, again an alpine climber, Hermann Buhl at Nanga Parbat. Afterwards, we had again British, French again, Americans on Gasherbrum I, Chinese on the last one because it was in Tibet. They didn’t give a permit to foreigners or they did it by themselves. The Japanese did an 8,000-meter peak. And these were the nations. They had history before the Second World War.

In the ‘70s, the whole thing changed. In the beginning of the ‘70s, my generation went to do the difficult routes, not anymore the summits. We reached on the end the summit, but the summit was only the end. We tried to do the most difficult routes.

But during this time, mathematically speaking, if you climbed 8,000-meter peaks ten times, you were just about guaranteed to die.

Reinhold Messner: Yeah. For me, the guarantee to die was 99 percent. I had to die. But I am the exception. I was lucky. I was prepared. I had this opportunity to learn in my young years and so on.

Some people might say, “That’s crazy.”

Reinhold Messner: No, that’s not crazy. I was very well organized in my things. I am an exceptional worker, not only a risk taker. And I was not in competition with anybody. Many people died because they were in competition. For example, the Polish climbers, the Czech climbers — not the Russians — the Russians could go on their own mountains in Crimea and the Khinjan. But the Polish, the Czechs, the Hungarians, they could not go. The Slovenians. They were in these communist systems. They could not go to the 8,000-meter peaks. When they could go, they went in so high-risk. More than 80 percent of the leading Polish climbers of the ‘80s died on the high peaks — also Kukuczka, the best one, died. And now again the Slovenians are the best climbers of the world. This small country, there is between them a hard competition, and they had not a chance to express themselves in the great years, in the ‘50s and the ‘60s, beginning of the ‘70s, when I had my opportunity.

Do you feel an adrenaline rush after a big successful climb?

Reinhold Messner: The adrenaline is stronger when you start, not in the end. In the end, you’re calming down, especially if something has happened. If nothing has happened, everything is running after your plan, which you started to prepare years before.

In ’78, in May, after Everest, being back in Katmandu, capital of Nepal, I went to the government to ask for a solo permit on Everest. And they said, “No chance. It’s forbidden.” I cannot get a permit. Afterwards, I went to China — to Beijing — to ask the Chinese because Everest is a border mountain, to get the permit, and they give me immediately a permit to go. It was costly, but anyway, I got the permit. And I had more than two years to prepare mentally for Everest alone. And in these two years, no day passed without thinking a moment what I do when, what I take with me, which route I will exactly go.

Generally, before going, I know where, generally, I go. In detail, I do it from the base camp with binoculars, without binoculars. And afterwards, step-by-step, but these are the very small details. And on Everest, searching for the route, for the way, is easier than in the Dolomites because in the Dolomites you have vertical walls, and you can’t see from below — especially in early winter — with the binoculars. There’s a little bit of snow. Where there’s a little bit of snow, there’s a hold. But in detail, you cannot say if you’re really able to hold yourself on this small hold. So you have a general route in your mind. It’s like a picture in your mind. And you know, during climbing, where you are now in the route, which is here. You are in reality and here. This should match perfectly. And so you know now you have to go to the right, on the right side. But how you handle it in the next minutes or hours — sometimes you need hours for five meters.

Early in your career, you lost some of your toes, is that right? How many toes?

Reinhold Messner: Seven, partly.

I think some people would have stopped then. Why did you keep going?

Reinhold Messner: Because I had the possibility to go further, and I understood quite quickly when in high altitude, the shoes are so heavy and so isolated that I can go also quite well without those. I did more than 100 expeditions without these seven toes. I did only two expeditions before going to the big mountains.

Does it hurt?

Reinhold Messner: It hurts sometimes, a little bit. It’s part of my life, like I have this nose; I have no toes — or missing seven toes. Not totally missing them — some are totally gone — the left foot, only one toe is left. And on the other one, parts are cut off. So for rock climbing, I need different shoes.

If it wasn’t competition with somebody else, what was the drive that made you do something where you had a 99 percent chance of dying?

Reinhold Messner: The knowledge that life is great if you go further to invent something and to do it. This is the key. This is the key that generates my life. One key is that I am fighting to be a self-sufficient person who can do what he likes. I don’t like anybody around me telling me, “You should not do this and you should do this. And you should go down there.”

What do you feel at the top of Mount Everest? There are billions of people on Earth, and for one moment, when you are on top of the world, five miles up, you’re the only one up there. You’re literally higher than all of us. Can you tell us what kind of feeling you have at that moment?

Reinhold Messner: Nothing. You have the feeling you are going in, in a situation. I sat down and I was very tired. Sitting and resting, and after a while, I had the power to get up for going down. This was all. The big emotions are coming when you go back to life, when you hear the first water running. Up there is no running water.

What does it feel like when you come back from the mountaintop? What are the emotions?

Reinhold Messner: You come back to life, to be alive. Up there you are so exposed. You’re on the limit of exposure, to less oxygen. It’s very cold. No water. You have to make water. There’s snow — okay, ice. You can make water. Food is not so important. But coming back, you have the warmth of the sun. The sun is warm down there. Up there, the sun is not giving energy. You have people around you. You have birds around you. You have insects around you. You are in the middle of the life. And this is the strong moment. And this moment is like to be reborn. But in this case, not your mother gives you life — but you, by yourself, you’ve conquered your life back. You went in an area — in a world — which is not made for human beings, and you feel it every second. This is not made for us. But if you come back to the place which is made for human beings, you are reborn, and you have totally life before you. And with all your fantasy and energy, you start the next project, for having again this feeling of being reborn.

But if you do something your whole lifetime, normally it is becoming boring because after a while you know how to handle it. So after the 8,000-meter peaks, I decided, okay, that’s enough now. I would not like to repeat myself once more and once more, and look how the people are clapping if I climb one more 8,000-meter peak. I decided to do something new. And I was totally unable to handle this new thing, and I had to learn. The best part is always the beginning. The beginning and maybe after one or two years, when you are able to handle it, you can understand the problems. And you can begin to go above what was done before you — to go in unknown areas.

One of the things you’ve done that’s so fascinating is your search for the Yeti.

Reinhold Messner: First of all, you have to understand that the Yeti is a legend. The Yeti story is a legend. And in Asia, where this legend was growing and taught from generation to generation, it’s a legend. It was living in the north foothill of the Himalayas. And on certain places, the people went from the north to the south, and with the people came also the legend from the north to the south. And the local people are not calling this strange being — this big beast or whatever you call it — “Yeti.” The word “Yeti” is an invention of a British journalist. He put a few words together, and he came home and said, “In Himalaya, there’s a Yeti. This Yeti is the snowman.” So the people are thinking he’s a man, a hairy man, the snowman. But this is all wrong.

And I could brief that proof, that the Yeti legend is still existing, and many people in the Himalayas heard about it, while none of them have seen ever this beast, this creature. And this is all of it. But there is an animal, which is the base of this Yeti figure. We call it Yeti figure, but they call it different. And I did the book, how I found out and how I did. Now American genetic specialists, they proved it genetically that this special bear — it’s a special bear — is the base of this legend. And around this bear, they told stories a little bit differently. But I found, in the eastern part of the Himalayas and in the western part, where there are totally different cultures and languages and religions, the same story. So we know it was once in the whole Himalayas.

When you saw this bear, what did it look like?