“The dark ages for Deaf education in America” began in

1) 1817.

2) 1880.

3) 1920.

4) 1960.

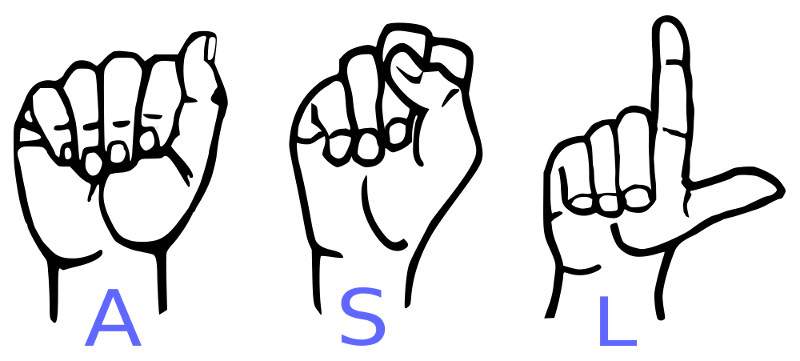

Hearing loss is a partial or total inability to hear. It affects about a billion people on earth. Around a hundred million of these are completely deaf and require special ways of communicating. One of these ways is sign language. Sign language is a language that uses hand gestures that are modified by facial expressions. Hand gestures are mainly used for words, while most grammar comes from facial expressions. American Sign Language or ASL is a language used by the Deaf community in the USA.

ASL is surrounded by a lot of myths and misconceptions. One of the most common myths is that it is simply a visual code for English and not a real language. In fact, ASL and English are two completely separate languages, each with their own grammar. Although ASL does sometimes use fingerspelling, when each letter of a word is spelled out by a particular gesture, it is mostly used for names. Another popular misconception is that ASL is a universal language understood by all signers in the world. Actually, there are hundreds of sign languages, all naturally developed by the Deaf communities in different countries.

It is interesting that ASL is specific to the USA, while other Englishspeaking countries, such as the UK or Australia have their own sign languages. In a way, due to its history, ASL is closer to French Sign Language than it is to British Sign Language.

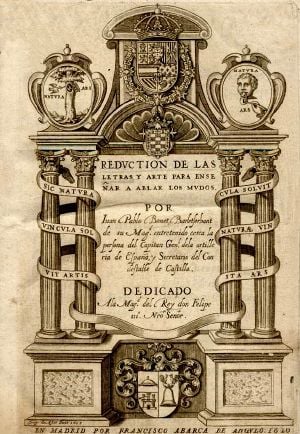

The origins of ASL can be traced back to a couple of influences. In the 1600s the first regional sign languages naturally developed in the American colonies. They appeared in places like Martha’s Vineyard, where a large number of deaf people happened to be part of the community. Another major influence was French Sign Language. In 1817 Laurent Clerc, a deaf teacher from France, and Thomas Gallaudet, a hearing American educator, founded the first American school for the deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. The blending of regional sign language and French Sign Language formed the basis of ASL today.

In the 19th century ASL flourished through Deaf schools, which had great success utilizing a combination of ASL and written English. However, a change in Deaf education occurred in 1880 that is still affecting the Deaf community today. In the 2nd International Congress on Deaf Education that met in Milan and where no deaf people were allowed to participate in the discussion of sign language, the majority voted in favor of oral education for all deaf children. This meant teaching them to read lips and imitate speech. It was believed that the exaggerated facial expressions, which include movements of eyes, eyebrows, mouth, tongue and lips and are part of any sign language, were unpleasant to hearing people and could even horrify them. In addition, sign languages were thought to have no grammar.

In the following 40 years over 80% of the Deaf schools in the USA, as well as in many other countries, switched to an oral method of instruction. This became known as “the dark ages for Deaf education in America”. The number of deaf teachers in the schools dropped significantly, as they were considered inferior, unable to teach the children speech. Students were not allowed to use ASL during the lessons. Fortunately, the children in these schools still used ASL between and after classes to exchange information and just talk to each other. The effectiveness of the oral approach remained a contentious issue for the next century and a half, with a resurgence of ASL in the 1960s.

«Canadian Sign Language» redirects here. For French Canadian Sign Language, see Quebec Sign Language. For the sign language specific to Canada’s Atlantic provinces, see Maritime Sign Language.

| American Sign Language | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Native to | United States, Canada |

| Region | English-speaking North America |

| Signers | Native signers: 730,000 (2006)[1] L2 signers: 130,000 (2006)[1] |

|

Language family |

French Sign-based (possibly a creole with Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language)

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

None are widely accepted si5s (ASLwrite), ASL-phabet, Stokoe notation, SignWriting |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

none |

|

Recognised minority |

Ontario only in domains of: legislation, education and judiciary proceedings.[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ase |

| Glottolog | asli1244 ASL familyamer1248 ASL proper |

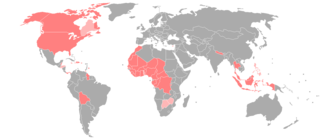

Areas where ASL or a dialect/derivative thereof is the national sign language Areas where ASL is in significant use alongside another sign language |

American Sign Language (ASL) is a natural language[4] that serves as the predominant sign language of Deaf communities in the United States of America and most of Anglophone Canada. ASL is a complete and organized visual language that is expressed by employing both manual and nonmanual features.[5] Besides North America, dialects of ASL and ASL-based creoles are used in many countries around the world, including much of West Africa and parts of Southeast Asia. ASL is also widely learned as a second language, serving as a lingua franca. ASL is most closely related to French Sign Language (LSF). It has been proposed that ASL is a creole language of LSF, although ASL shows features atypical of creole languages, such as agglutinative morphology.

ASL originated in the early 19th century in the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in West Hartford, Connecticut, from a situation of language contact. Since then, ASL use has been propagated widely by schools for the deaf and Deaf community organizations. Despite its wide use, no accurate count of ASL users has been taken. Reliable estimates for American ASL users range from 250,000 to 500,000 persons, including a number of children of deaf adults and other hearing individuals.

ASL signs have a number of phonemic components, such as movement of the face, the torso, and the hands. ASL is not a form of pantomime although iconicity plays a larger role in ASL than in spoken languages. English loan words are often borrowed through fingerspelling, although ASL grammar is unrelated to that of English. ASL has verbal agreement and aspectual marking and has a productive system of forming agglutinative classifiers. Many linguists believe ASL to be a subject–verb–object language. However, there are several alternative proposals to account for ASL word order.

Classification[edit]

Travis Dougherty explains and demonstrates the ASL alphabet. Voice-over interpretation by Gilbert G. Lensbower.

ASL emerged as a language in the American School for the Deaf (ASD), founded by Thomas Gallaudet in 1817,[6]: 7 which brought together Old French Sign Language, various village sign languages, and home sign systems. ASL was created in that situation by language contact.[7]: 11 [a] ASL was influenced by its forerunners but distinct from all of them.[6]: 7

The influence of French Sign Language (LSF) on ASL is readily apparent; for example, it has been found that about 58% of signs in modern ASL are cognate to Old French Sign Language signs.[6]: 7 [7]: 14 However, that is far less than the standard 80% measure used to determine whether related languages are actually dialects.[7]: 14 That suggests that nascent ASL was highly affected by the other signing systems brought by the ASD students although the school’s original director, Laurent Clerc, taught in LSF.[6]: 7 [7]: 14 In fact, Clerc reported that he often learned the students’ signs rather than conveying LSF:[7]: 14

I see, however, and I say it with regret, that any efforts that we have made or may still be making, to do better than, we have inadvertently fallen somewhat back of Abbé de l’Épée. Some of us have learned and still learn signs from uneducated pupils, instead of learning them from well instructed and experienced teachers.

— Clerc, 1852, from Woodward 1978:336

It has been proposed that ASL is a creole in which LSF is the superstrate language and the native village sign languages are substrate languages.[8]: 493 However, more recent research has shown that modern ASL does not share many of the structural features that characterize creole languages.[8]: 501 ASL may have begun as a creole and then undergone structural change over time, but it is also possible that it was never a creole-type language.[8]: 501 There are modality-specific reasons that sign languages tend towards agglutination, such as the ability to simultaneously convey information via the face, head, torso, and other body parts. That might override creole characteristics such as the tendency towards isolating morphology.[8]: 502 Additionally, Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet may have used an artificially constructed form of manually coded language in instruction rather than true LSF.[8]: 497

Although the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia share English as a common oral and written language, ASL is not mutually intelligible with either British Sign Language (BSL) or Auslan.[9]: 68 All three languages show degrees of borrowing from English, but that alone is not sufficient for cross-language comprehension.[9]: 68 It has been found that a relatively high percentage (37–44%) of ASL signs have similar translations in Auslan, which for oral languages would suggest that they belong to the same language family.[9]: 69 However, that does not seem justified historically for ASL and Auslan, and it is likely that the resemblance is caused by the higher degree of iconicity in sign languages in general as well as contact with English.[9]: 70

American Sign Language is growing in popularity in many states. Many high school and university students desire to take it as a foreign language, but until recently, it was usually not considered a creditable foreign language elective. ASL users, however, have a very distinct culture, and they interact very differently when they talk. Their facial expressions and hand movements reflect what they are communicating. They also have their own sentence structure, which sets the language apart.[10]

American Sign Language is now being accepted by many colleges as a language eligible for foreign language course credit;[11] many states are making it mandatory to accept it as such.[12] in some states however, this is only true with regard to high school coursework.

History[edit]

A sign language interpreter at a presentation

Prior to the birth of ASL, sign language had been used by various communities in the United States.[6]: 5 In the United States, as elsewhere in the world, hearing families with deaf children have historically employed ad hoc home sign, which often reaches much higher levels of sophistication than gestures used by hearing people in spoken conversation.[6]: 5 As early as 1541 at first contact by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, there were reports that the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains widely spoke a sign language to communicate across vast national and linguistic lines.[13]: 80

In the 19th century, a «triangle» of village sign languages developed in New England: one in Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts; one in Henniker, New Hampshire, and one in Sandy River Valley, Maine.[14] Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL), which was particularly important for the history of ASL, was used mainly in Chilmark, Massachusetts.[6]: 5–6 Due to intermarriage in the original community of English settlers of the 1690s, and the recessive nature of genetic deafness, Chilmark had a high 4% rate of genetic deafness.[6]: 5–6 MVSL was used even by hearing residents whenever a deaf person was present,[6]: 5–6 and also in some situations where spoken language would be ineffective or inappropriate, such as during church sermons or between boats at sea.[15]

ASL is thought to have originated in the American School for the Deaf (ASD), founded in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817.[6]: 4 Originally known as The American Asylum, At Hartford, For The Education And Instruction Of The Deaf And Dumb, the school was founded by the Yale graduate and divinity student Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet.[16][17] Gallaudet, inspired by his success in demonstrating the learning abilities of a young deaf girl Alice Cogswell, traveled to Europe in order to learn deaf pedagogy from European institutions.[16] Ultimately, Gallaudet chose to adopt the methods of the French Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, and convinced Laurent Clerc, an assistant to the school’s founder Charles-Michel de l’Épée, to accompany him back to the United States.[16][b] Upon his return, Gallaudet founded the ASD on April 15, 1817.[16]

The largest group of students during the first seven decades of the school were from Martha’s Vineyard, and they brought MVSL with them.[7]: 10 There were also 44 students from around Henniker, New Hampshire, and 27 from the Sandy River valley in Maine, each of which had their own village sign language.[7]: 11 [c] Other students brought knowledge of their own home signs.[7]: 11 Laurent Clerc, the first teacher at ASD, taught using French Sign Language (LSF), which itself had developed in the Parisian school for the deaf established in 1755.[6]: 7 From that situation of language contact, a new language emerged, now known as ASL.[6]: 7

American Sign Language Convention of March 2008 in Austin, Texas

More schools for the deaf were founded after ASD, and knowledge of ASL spread to those schools.[6]: 7 In addition, the rise of Deaf community organizations bolstered the continued use of ASL.[6]: 8 Societies such as the National Association of the Deaf and the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf held national conventions that attracted signers from across the country.[7]: 13 All of that contributed to ASL’s wide use over a large geographical area, atypical of a sign language.[7]: 14 [7]: 12

While oralism, an approach to educating deaf students focusing on oral language, had previously been used in American schools, the Milan Congress made it dominant and effectively banned the use of sign languages at schools in the United States and Europe. However, the efforts of Deaf advocates and educators, more lenient enforcement of the Congress’ mandate, and the use of ASL in religious education and proselytism ensured greater use and documentation compared to European sign languages, albeit more influenced by fingerspelled loanwords and borrowed idioms from English as students were societally pressured to achieve fluency in spoken language.[20] Nevertheless, oralism remained the prominent method of deaf education up to the 1950s.[21] Linguists did not consider sign language to be true «language» but as something inferior.[21] Recognition of the legitimacy of ASL was achieved by William Stokoe, a linguist who arrived at Gallaudet University in 1955 when that was still the dominant assumption.[21] Aided by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Stokoe argued for manualism, the use of sign language in deaf education.[21][22] Stokoe noted that sign language shares the important features that oral languages have as a means of communication, and even devised a transcription system for ASL.[21] In doing so, Stokoe revolutionized both deaf education and linguistics.[21] In the 1960s, ASL was sometimes referred to as «Ameslan», but that term is now considered obsolete.[23]

Population[edit]

Counting the number of ASL signers is difficult because ASL users have never been counted by the American census.[24]: 1 [d] The ultimate source for current estimates of the number of ASL users in the United States is a report for the National Census of the Deaf Population (NCDP) by Schein and Delk (1974).[24]: 17 Based on a 1972 survey of the NCDP, Schein and Delk provided estimates consistent with a signing population between 250,000 and 500,000.[24]: 26 The survey did not distinguish between ASL and other forms of signing; in fact, the name «ASL» was not yet in widespread use.[24]: 18

Incorrect figures are sometimes cited for the population of ASL users in the United States based on misunderstandings of known statistics.[24]: 20 Demographics of the deaf population have been confused with those of ASL use since adults who become deaf late in life rarely use ASL in the home.[24]: 21 That accounts for currently-cited estimations that are greater than 500,000; such mistaken estimations can reach as high as 15,000,000.[24]: 1, 21 A 100,000-person lower bound has been cited for ASL users; the source of that figure is unclear, but it may be an estimate of prelingual deafness, which is correlated with but not equivalent to signing.[24]: 22

ASL is sometimes incorrectly cited as the third- or fourth-most-spoken language in the United States.[24]: 15, 22 Those figures misquote Schein and Delk (1974), who actually concluded that ASL speakers constituted the third-largest population «requiring an interpreter in court».[24]: 15, 22 Although that would make ASL the third-most used language among monolinguals other than English, it does not imply that it is the fourth-most-spoken language in the United States since speakers of other languages may also speak English.[24]: 21–22

Geographic distribution[edit]

ASL is used throughout Anglo-America.[7]: 12 That contrasts with Europe, where a variety of sign languages are used within the same continent.[7]: 12 The unique situation of ASL seems to have been caused by the proliferation of ASL through schools influenced by the American School for the Deaf, wherein ASL originated, and the rise of community organizations for the Deaf.[7]: 12–14

Throughout West Africa, ASL-based sign languages are signed by educated Deaf adults.[25]: 410 Such languages, imported by boarding schools, are often considered by associations to be the official sign languages of their countries and are named accordingly, such as Nigerian Sign Language, Ghanaian Sign Language.[25]: 410 Such signing systems are found in Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Liberia, Mauritania, Mali, Nigeria, and Togo.[25]: 406 Due to lack of data, it is still an open question how similar those sign languages are to the variety of ASL used in America.[25]: 411

In addition to the aforementioned West African countries, ASL is reported to be used as a first language in Barbados, Bolivia, Cambodia[26] (alongside Cambodian Sign Language), the Central African Republic, Chad, China (Hong Kong), the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Jamaica, Kenya, Madagascar, the Philippines, Singapore, and Zimbabwe.[1] ASL is also used as a lingua franca throughout the deaf world, widely learned as a second language.[1]

Regional variation[edit]

Sign production[edit]

Sign production can often vary according to location. Signers from the South tend to sign with more flow and ease. Native signers from New York have been reported as signing comparatively quicker and sharper. Sign production of native Californian signers has also been reported as being fast. Research on that phenomenon often concludes that the fast-paced production for signers from the coasts could be due to the fast-paced nature of living in large metropolitan areas. That conclusion also supports how the ease with which Southern sign could be caused by the easygoing environment of the South in comparison to that of the coasts.[27]

Sign production can also vary depending on age and native language. For example, sign production of letters may vary in older signers. Slight differences in finger spelling production can be a signal of age. Additionally, signers who learned American Sign Language as a second language vary in production. For Deaf signers who learned a different sign language before learning American Sign Language, qualities of their native language may show in their ASL production. Some examples of that varied production include fingerspelling towards the body, instead of away from it, and signing certain movement from bottom to top, instead of top to bottom. Hearing people who learn American Sign Language also have noticeable differences in signing production. The most notable production difference of hearing people learning American Sign Language is their rhythm and arm posture.[28]

Sign variants[edit]

Most popularly, there are variants of the signs for English words such as «birthday», «pizza», «Halloween», «early», and «soon», just a sample of the most commonly recognized signs with variants based on regional change. The sign for «school» is commonly varied between black and white signers. The variation between signs produced by black and white signers is sometimes referred to as Black American Sign Language.[29]

History and implications[edit]

The prevalence of residential Deaf schools can account for much of the regional variance of signs and sign productions across the United States. Deaf schools often serve students of the state in which the school resides. That limited access to signers from other regions, combined with the residential quality of Deaf Schools promoted specific use of certain sign variants. Native signers did not have much access to signers from other regions during the beginning years of their education. It is hypothesized that because of that seclusion, certain variants of a sign prevailed over others due to the choice of variant used by the student of the school/signers in the community.

However, American Sign Language does not appear to be vastly varied in comparison to other signed languages. That is because when Deaf education was beginning in the United States, many educators flocked to the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, whose central location for the first generation of educators in Deaf education to learn American Sign Language allows ASL to be more standardized than its variant.[29]

Varieties[edit]

About – General sign (Canadian ASL)[30]

About – Atlantic Variation (Canadian ASL)[30]

About – Ontario Variation (Canadian ASL)[30]

Varieties of ASL are found throughout the world. There is little difficulty in comprehension among the varieties of the United States and Canada.[1]

Just as there are accents in speech, there are regional accents in sign. People from the South sign slower than people in the North—even people from northern and southern Indiana have different styles.

Mutual intelligibility among those ASL varieties is high, and the variation is primarily lexical.[1] For example, there are three different words for English about in Canadian ASL; the standard way, and two regional variations (Atlantic and Ontario).[30] Variation may also be phonological, meaning that the same sign may be signed in a different way depending on the region. For example, an extremely common type of variation is between the handshapes /1/, /L/, and /5/ in signs with one handshape.[31]

There is also a distinct variety of ASL used by the Black Deaf community.[1] Black ASL evolved as a result of racially segregated schools in some states, which included the residential schools for the deaf.[32]: 4 Black ASL differs from standard ASL in vocabulary, phonology, and some grammatical structure.[1][32]: 4 While African American English (AAE) is generally viewed as more innovating than standard English, Black ASL is more conservative than standard ASL, preserving older forms of many signs.[32]: 4 Black sign language speakers use more two-handed signs than in mainstream ASL, are less likely to show assimilatory lowering of signs produced on the forehead (e.g. KNOW) and use a wider signing space.[32]: 4 Modern Black ASL borrows a number of idioms from AAE; for instance, the AAE idiom «I feel you» is calqued into Black ASL.[32]: 10

ASL is used internationally as a lingua franca, and a number of closely related sign languages derived from ASL are used in many different countries.[1] Even so, there have been varying degrees of divergence from standard ASL in those imported ASL varieties. Bolivian Sign Language is reported to be a dialect of ASL, no more divergent than other acknowledged dialects.[33] On the other hand, it is also known that some imported ASL varieties have diverged to the extent of being separate languages. For example, Malaysian Sign Language, which has ASL origins, is no longer mutually comprehensible with ASL and must be considered its own language.[34] For some imported ASL varieties, such as those used in West Africa, it is still an open question how similar they are to American ASL.[25]: 411

When communicating with hearing English speakers, ASL-speakers often use what is commonly called Pidgin Signed English (PSE) or ‘contact signing’, a blend of English structure with ASL vocabulary.[1][35] Various types of PSE exist, ranging from highly English-influenced PSE (practically relexified English) to PSE which is quite close to ASL lexically and grammatically, but may alter some subtle features of ASL grammar.[35] Fingerspelling may be used more often in PSE than it is normally used in ASL.[36] There have been some constructed sign languages, known as Manually Coded English (MCE), which match English grammar exactly and simply replace spoken words with signs; those systems are not considered to be varieties of ASL.[1][35]

Tactile ASL (TASL) is a variety of ASL used throughout the United States by and with the deaf-blind.[1] It is particularly common among those with Usher’s syndrome.[1] It results in deafness from birth followed by loss of vision later in life; consequently, those with Usher’s syndrome often grow up in the Deaf community using ASL, and later transition to TASL.[37] TASL differs from ASL in that signs are produced by touching the palms, and there are some grammatical differences from standard ASL in order to compensate for the lack of nonmanual signing.[1]

ASL changes over time and from generation to generation. The sign for telephone has changed as the shape of phones and the manner of holding them have changed.[38] The development of telephones with screens has also changed ASL, encouraging the use of signs that can be seen on small screens.[38]

Stigma[edit]

In 2013, the White House published a response to a petition that gained over 37,000 signatures to officially recognize American Sign Language as a community language and a language of instruction in schools. The response is titled «there shouldn’t be any stigma about American Sign Language» and addressed that ASL is a vital language for the Deaf and hard of hearing. Stigmas associated with sign languages and the use of sign for educating children often lead to the absence of sign during periods in children’s lives when they can access languages most effectively.[39] Scholars such as Beth S. Benedict advocate not only for bilingualism (using ASL and English training) but also for early childhood intervention for children who are deaf. York University psychologist Ellen Bialystok has also campaigned for bilingualism, arguing that those who are bilingual acquire cognitive skills that may help to prevent dementia later in life.[40]

Most children born to deaf parents are hearing.[41]: 192 Known as CODAs («Children Of Deaf Adults»), they are often more culturally Deaf than deaf children, most of whom are born to hearing parents.[41]: 192 Unlike many deaf children, CODAs acquire ASL as well as Deaf cultural values and behaviors from birth.[41]: 192 Such bilingual hearing children may be mistakenly labeled as being «slow learners» or as having «language difficulties» because of preferential attitudes towards spoken language.[41]: 195

Writing systems[edit]

Although there is no well-established writing system for ASL,[42] written sign language dates back almost two centuries. The first systematic writing system for a sign language seems to be that of Roch-Ambroise Auguste Bébian, developed in 1825.[43]: 153 However, written sign language remained marginal among the public.[43]: 154 In the 1960s, linguist William Stokoe created Stokoe notation specifically for ASL. It is alphabetic, with a letter or diacritic for every phonemic (distinctive) hand shape, orientation, motion, and position, though it lacks any representation of facial expression, and is better suited for individual words than for extended passages of text.[44] Stokoe used that system for his 1965 A Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles.[45]

SignWriting, proposed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton,[43]: 154 is the first writing system to gain use among the public and the first writing system for sign languages to be included in the Unicode Standard.[46] SignWriting consists of more than 5000 distinct iconic graphs/glyphs.[43]: 154 Currently, it is in use in many schools for the Deaf, particularly in Brazil, and has been used in International Sign forums with speakers and researchers in more than 40 countries, including Brazil, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Slovenia, Tunisia, and the United States. Sutton SignWriting has both a printed and an electronically produced form so that persons can use the system anywhere that oral languages are written (personal letters, newspapers, and media, academic research). The systematic examination of the International Sign Writing Alphabet (ISWA) as an equivalent usage structure to the International Phonetic Alphabet for spoken languages has been proposed.[47] According to some researchers, SignWriting is not a phonemic orthography and does not have a one-to-one map from phonological forms to written forms.[43]: 163 That assertion has been disputed, and the process for each country to look at the ISWA and create a phonemic/morphemic assignment of features of each sign language was proposed by researchers Msc. Roberto Cesar Reis da Costa and Madson Barreto in a thesis forum on June 23, 2014.[48] The SignWriting community has an open project on Wikimedia Labs to support the various Wikimedia projects on Wikimedia Incubator[49] and elsewhere involving SignWriting. The ASL Wikipedia request was marked as eligible in 2008[50] and the test ASL Wikipedia has 50 articles written in ASL using SignWriting.

The most widely used transcription system among academics is HamNoSys, developed at the University of Hamburg.[43]: 155 Based on Stokoe Notation, HamNoSys was expanded to about 200 graphs in order to allow transcription of any sign language.[43]: 155 Phonological features are usually indicated with single symbols, though the group of features that make up a handshape is indicated collectively with a symbol.[43]: 155

Comparison of ASL writing systems. Sutton SignWriting is on the left, followed by Si5s, then Stokoe notation in the center, with SignFont and its simplified derivation ASL-phabet on the right.

Several additional candidates for written ASL have appeared over the years, including SignFont, ASL-phabet, and Si5s.

For English-speaking audiences, ASL is often glossed using English words. Such glosses are typically all-capitalized and are arranged in ASL order. For example, the ASL sentence DOG NOW CHASE>IX=3 CAT, meaning «the dog is chasing the cat», uses NOW to mark ASL progressive aspect and shows ASL verbal inflection for the third person (written with >IX=3). However, glossing is not used to write the language for speakers of ASL.[42]

Phonology[edit]

Phonemic handshape /2/

[+ closed thumb][6]: 12

Phonemic handshape /3/

[− closed thumb][6]: 12

Each sign in ASL is composed of a number of distinctive components, generally referred to as parameters. A sign may use one hand or both. All signs can be described using the five parameters involved in signed languages, which are handshape, movement, palm orientation, location and nonmanual markers.[6]: 10 Just as phonemes of sound distinguish meaning in spoken languages, those parameters are the phonemes that distinguish meaning in signed languages like ASL.[51] Changing any one of them may change the meaning of a sign, as illustrated by the ASL signs THINK and DISAPPOINTED:

|

|

There are also meaningful nonmanual signals in ASL,[6]: 49 which may include movement of the eyebrows, the cheeks, the nose, the head, the torso, and the eyes.[6]: 49

William Stokoe proposed that such components are analogous to the phonemes of spoken languages.[43]: 601:15 [e] There has also been a proposal that they are analogous to classes like place and manner of articulation.[43]: 601:15 As in spoken languages, those phonological units can be split into distinctive features.[6]: 12 For instance, the handshapes /2/ and /3/ are distinguished by the presence or absence of the feature [± closed thumb], as illustrated to the right.[6]: 12 ASL has processes of allophony and phonotactic restrictions.[6]: 12, 19 There is ongoing research into whether ASL has an analog of syllables in spoken language.[6]: 1

Grammar[edit]

Two men and a woman signing

Morphology[edit]

ASL has a rich system of verbal inflection, which involves both grammatical aspect: how the action of verbs flows in time—and agreement marking.[6]: 27–28 Aspect can be marked by changing the manner of movement of the verb; for example, continuous aspect is marked by incorporating rhythmic, circular movement, while punctual aspect is achieved by modifying the sign so that it has a stationary hand position.[6]: 27–28 Verbs may agree with both the subject and the object, and are marked for number and reciprocity.[6]: 28 Reciprocity is indicated by using two one-handed signs; for example, the sign SHOOT, made with an L-shaped handshape with inward movement of the thumb, inflects to SHOOT[reciprocal], articulated by having two L-shaped hands «shooting» at each other.[6]: 29

ASL has a productive system of classifiers, which are used to classify objects and their movement in space.[6]: 26 For example, a rabbit running downhill would use a classifier consisting of a bent V classifier handshape with a downhill-directed path; if the rabbit is hopping, the path is executed with a bouncy manner.[6]: 26 In general, classifiers are composed of a «classifier handshape» bound to a «movement root».[6]: 26 The classifier handshape represents the object as a whole, incorporating such attributes as surface, depth, and shape, and is usually very iconic.[52] The movement root consists of a path, a direction and a manner.[6]: 26

Fingerspelling[edit]

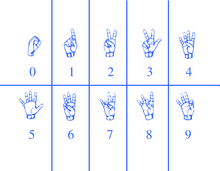

The American manual alphabet and numbers

ASL possesses a set of 26 signs known as the American manual alphabet, which can be used to spell out words from the English language.[53] Such signs make use of the 19 handshapes of ASL. For example, the signs for ‘p’ and ‘k’ use the same handshape but different orientations. A common misconception is that ASL consists only of fingerspelling; although such a method (Rochester Method) has been used, it is not ASL.[36]

Fingerspelling is a form of borrowing, a linguistic process wherein words from one language are incorporated into another.[36] In ASL, fingerspelling is used for proper nouns and for technical terms with no native ASL equivalent.[36] There are also some other loan words which are fingerspelled, either very short English words or abbreviations of longer English words, e.g. O-N from English ‘on’, and A-P-T from English ‘apartment’.[36] Fingerspelling may also be used to emphasize a word that would normally be signed otherwise.[36]

Syntax[edit]

ASL is a subject–verb–object (SVO) language, but various phenomena affect that basic word order.[54] Basic SVO sentences are signed without any pauses:[29]

FATHER

LOVE

CHILD

«The father loves the child.»[29]

However, other word orders may also occur since ASL allows the topic of a sentence to be moved to sentence-initial position, a phenomenon known as topicalization.[55] In object–subject–verb (OSV) sentences, the object is topicalized, marked by a forward head-tilt and a pause:[56]

CHILDtopic,

FATHER

LOVE

«The father loves the child.»[56]

Besides, word orders can be obtained through the phenomenon of subject copy in which the subject is repeated at the end of the sentence, accompanied by head nodding for clarification or emphasis:[29]

FATHER

LOVE

CHILD

FATHERcopy

«The father loves the child.»[29]

ASL also allows null subject sentences whose subject is implied, rather than stated explicitly. Subjects can be copied even in a null subject sentence, and the subject is then omitted from its original position, yielding a verb–object–subject (VOS) construction:[56]

LOVE

CHILD

FATHERcopy

«The father loves the child.»[56]

Topicalization, accompanied with a null subject and a subject copy, can produce yet another word order, object–verb–subject (OVS).

CHILDtopic,

LOVE

FATHERcopy

«The father loves the child.»[56]

Those properties of ASL allow it a variety of word orders, leading many to question which is the true, underlying, «basic» order. There are several other proposals that attempt to account for the flexibility of word order in ASL. One proposal is that languages like ASL are best described with a topic–comment structure whose words are ordered by their importance in the sentence, rather than by their syntactic properties.[57] Another hypothesis is that ASL exhibits free word order, in which syntax is not encoded in word order but can be encoded by other means such as head nods, eyebrow movement, and body position.[54]

Iconicity[edit]

Common misconceptions are that signs are iconically self-explanatory, that they are a transparent imitation of what they mean, or even that they are pantomime.[58] In fact, many signs bear no resemblance to their referent because they were originally arbitrary symbols, or their iconicity has been obscured over time.[58] Even so, in ASL iconicity plays a significant role; a high percentage of signs resemble their referents in some way.[59] That may be because the medium of sign, three-dimensional space, naturally allows more iconicity than oral language.[58]

In the era of the influential linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, it was assumed that the mapping between form and meaning in language must be completely arbitrary.[59] Although onomatopoeia is a clear exception, since words like ‘choo-choo’ bear clear resemblance to the sounds that they mimic, the Saussurean approach was to treat them as marginal exceptions.[60] ASL, with its significant inventory of iconic signs, directly challenges that theory.[61]

Research on acquisition of pronouns in ASL has shown that children do not always take advantage of the iconic properties of signs when they interpret their meaning.[62] It has been found that when children acquire the pronoun «you», the iconicity of the point (at the child) is often confused, being treated more like a name.[63] That is a similar finding to research in oral languages on pronoun acquisition. It has also been found that iconicity of signs does not affect immediate memory and recall; less iconic signs are remembered just as well as highly-iconic signs.[64]

See also[edit]

- American Sign Language grammar

- American Sign Language literature

- Baby sign language

- Bimodal bilingualism

- Great ape language, of which ASL has been one attempted mode

- Legal recognition of sign languages

- Pointing

- Sign name

- ASL interpreting

Notes[edit]

- ^ In particular, Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language, Henniker Sign Language, and Sandy River Valley Sign Language were brought to the school by students. They, in turn, appear to have been influenced by early British Sign Language and did not involve input from indigenous Native American sign systems. See Padden (2010:11), Lane, Pillard & French (2000:17), and Johnson & Schembri (2007:68).

- ^ The Abbé Charles-Michel de l’Épée, founder of the Parisian school Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, was the first to acknowledge that sign language could be used to educate the deaf. An oft-repeated folk tale states that while visiting a parishioner, Épee met two deaf daughters conversing with each other using LSF. The mother explained that her daughters were being educated privately by means of pictures. Épée is said to have been inspired by those deaf children when he established the first educational institution for the deaf.[18]

- ^ Whereas deafness was genetically recessive on Martha’s Vineyard, it was dominant in Henniker. On the one hand, this dominance likely aided the development of sign language in Henniker since families would be more likely to have the critical mass of deaf people necessary for the propagation of signing. On the other hand, in Martha’s Vineyard the deaf were more likely to have more hearing relatives, which may have fostered a sense of shared identity that led to more inter-group communication than in Henniker.[19]

- ^ Although some surveys of smaller scope measure ASL use, such as the California Department of Education recording ASL use in the home when children begin school, ASL use in the general American population has not been directly measured. See Mitchell et al. (2006:1).

- ^ Stokoe himself termed them cheremes, but other linguists have referred to them as phonemes. See Bahan (1996:11).

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n American Sign Language at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ Province of Ontario (2007). «Bill 213: An Act to recognize sign language as an official language in Ontario». Archived from the original on 2018-12-24. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

- ^ Education Policy Counsel at National Association of the Deaf. «States that Recognize American Sign Language as a Foreign Language» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ About American Sign Language, Deaf Research Library, Karen Nakamura

- ^ «American Sign Language». NIDCD. 2015-08-18. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Bahan (1996)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Padden (2010)

- ^ a b c d e Kegl (2008)

- ^ a b c d Johnson & Schembri (2007)

- ^ «ASL as a Foreign Language Fact Sheet». www.unm.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ Wilcox Phd, Sherman (May 2016). «Universities That Accept ASL In Fulfillment Of Foreign Language Requirements». Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ Burke, Sheila (April 26, 2017). «Bill Passes Requiring Sign Language Students Receive Credit». US News. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ Ceil Lucas, 1995, The Sociolinguistics of the Deaf Community

- ^ Lane, Pillard & French (2000:17)

- ^ Groce, Nora Ellen (1985). Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-27041-1. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

everyone here sign.

- ^ a b c d «A Brief History of ASD». American School for the Deaf. n.d. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ «A Brief History Of The American Asylum, At Hartford, For The Education And Instruction Of The Deaf And Dumb». 1893. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ See:

- Ruben, Robert J. (2005). «Sign language: Its history and contribution to the understanding of the biological nature of language». Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 125 (5): 464–7. doi:10.1080/00016480510026287. PMID 16092534. S2CID 1704351.

- Padden, Carol A. (2001). Folk Explanation in Language Survival in: Deaf World: A Historical Reader and Primary Sourcebook, Lois Bragg, Ed. New York: New York University Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0-8147-9853-9.

- ^ See Lane, Pillard & French (2000:39).

- ^ Shaw & Delaporte 2015, p. xii-xiv.

- ^ a b c d e f Armstrong & Karchmer (2002)

- ^ Stokoe, William C. 1960. Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf, Studies in linguistics: Occasional papers (No.

. Buffalo: Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo.

- ^ «American Sign Language, ASL or Ameslan». Handspeak.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-05. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mitchell et al. (2006)

- ^ a b c d e Nyst (2010)

- ^ Benoit Duchateau-Arminjon, 2013, Healing Cambodia One Child at a Time, p. 180.

- ^ Rogelio, Contreras (November 15, 2002). «Regional, Cultural, and Sociolinguistic Variation of ASL in the United States».

- ^ Gallaudet Department of Linguistics (2017-09-16), Do sign languages have accents?, archived from the original on 2021-10-30, retrieved 2018-04-27

- ^ a b c d e f Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-56368-283-4.

- ^ a b c d Bailey & Dolby (2002:1–2)

- ^ Lucas, Bayley & Valli (2003:36)

- ^ a b c d e Solomon (2010)

- ^ Bolivian Sign Language at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ Hurlbut (2003, 7. Conclusion)

- ^ a b c Nakamura, Karen (2008). «About ASL». Deaf Resource Library. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Costello (2008:xxv)

- ^ Collins (2004:33)

- ^ a b Morris, Amanda (2022-07-26). «How Sign Language Evolves as Our World Does». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Newman, Aaron J.; Bavelier, Daphne; Corina, David; Jezzard, Peter; Neville, Helen J. (2002). «A critical period for right hemisphere recruitment in American Sign Language processing». Nature Neuroscience. 5 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1038/nn775. PMID 11753419. S2CID 2745545.

- ^ Denworth, Ldyia (2014). I Can Hear You Whisper: An Intimate Journey through the Science of Sound and Language. USA: Penguin Group. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-525-95379-1.

- ^ a b c d Bishop & Hicks (2005)

- ^ a b Supalla & Cripps (2011, ASL Gloss as an Intermediary Writing System)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j van der Hulst & Channon (2010)

- ^ Armstrong, David F., and Michael A. Karchmer. «William C. Stokoe and the Study of Signed Languages.» Sign Language Studies 9.4 (2009): 389-397. Academic Search Premier. Web. 7 June 2012.

- ^ Stokoe, William C.; Dorothy C. Casterline; Carl G. Croneberg. 1965. A dictionary of American sign languages on linguistic principles. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet College Press

- ^ Everson, Michael; Slevinski, Stephen; Sutton, Valerie. «Proposal for encoding Sutton SignWriting in the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Charles Butler, Center for Sutton Movement Writing, 2014

- ^ Roberto Costa; Madson Barreto. «SignWriting Symposium Presentation 32». signwriting.org.

- ^ «Test wikis of sign languages». incubator.wikimedia.org.

- ^ «Request for ASL Wikipedia». meta.wikimedia.org.

- ^ Baker, Anne; van den Bogaerde, Beppie; Pfau, Roland; Schermer, Trude (2016). The Linguistics of Sign Languages : An Introduction. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027212306.

- ^ Valli & Lucas (2000:86)

- ^ Costello (2008:xxiv)

- ^ a b Neidle, Carol (2000). The Syntax of American Sign Language: Functional Categories and Hierarchical Structures. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-262-14067-6.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-56368-283-4.

- ^ a b c d e Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Lillo-Martin, Diane (November 1986). «Two Kinds of Null Arguments in American Sign Language». Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 4 (4): 415. doi:10.1007/bf00134469. S2CID 170784826.

- ^ a b c Costello (2008:xxiii)

- ^ a b Liddell (2002:60)

- ^ Liddell (2002:61)

- ^ Liddell (2002:62)

- ^ Thompson, Robin L.; Vinson, David P.; Vigliocco, Gabriella (March 2009). «The Link Between Form and Meaning in American Sign Language: Lexical Processing Effects». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 35 (2): 550–557. doi:10.1037/a0014547. ISSN 0278-7393. PMC 3667647. PMID 19271866.

- ^ Petitto, Laura A. (1987). «On the autonomy of language and gesture: Evidence from the acquisition of personal pronouns in American sign language». Cognition. 27 (1): 1–52. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(87)90034-5. PMID 3691016. S2CID 31570908.

- ^ Klima & Bellugi (1979:27)

Bibliography[edit]

- Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael (2002), «William C. Stokoe and the Study of Signed Languages», in Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael; Van Cleve, John (eds.), The Study of Signed Languages, Gallaudet University, pp. xi–xix, ISBN 978-1-56368-123-3, retrieved November 25, 2012

- Bahan, Benjamin (1996). Non-Manual Realization of Agreement in American Sign Language (PDF). Boston University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- Bailey, Carol; Dolby, Kathy (2002). The Canadian dictionary of ASL. Edmonton, AB: The University of Alberta Press. ISBN 978-0888643001.

- Bishop, Michele; Hicks, Sherry (2005). «Orange Eyes: Bimodal Bilingualism in Hearing Adults from Deaf Families». Sign Language Studies. 5 (2): 188–230. doi:10.1353/sls.2005.0001. S2CID 143557815.

- Collins, Steven (2004). Adverbial Morphemes in Tactile American Sign Language. Union Institute & University.

- Costello, Elaine (2008). American Sign Language Dictionary. Random House. ISBN 978-0375426162. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- Hurlbut, Hope (2003), «A Preliminary Survey of the Signed Languages of Malaysia», in Baker, Anne; van den Bogaerde, Beppie; Crasborn, Onno (eds.), Cross-linguistic perspectives in sign language research: selected papers from TISLR (PDF), Hamburg: Signum Verlag, pp. 31–46, archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09, retrieved December 3, 2012

- Johnson, Trevor; Schembri, Adam (2007). Australian Sign Language (Auslan): An introduction to sign language linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521540568. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Kegl, Judy (2008). «The Case of Signed Languages in the Context of Pidgin and Creole Studies». In Kouwenberg, Silvia; Singler, John (eds.). The Handbook of Pidgin and Creole Studies. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0521540568. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Klima, Edward S.; Bellugi, Ursula (1979). The signs of language. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-80796-9.

- Lane, Harlan; Pillard, Richard; French, Mary (2000). «Origins of the American Deaf-World». Sign Language Studies. 1 (1): 17–44. doi:10.1353/sls.2000.0003.

- Liddell, Scott (2002), «Modality Effects and Conflicting Agendas», in Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael; Van Cleve, John (eds.), The Study of Signed Languages, Gallaudet University, pp. xi–xix, ISBN 978-1-56368-123-3, retrieved November 26, 2012

- Lucas, Ceil; Bayley, Robert; Valli, Clayton (2003). What’s your sign for pizza?: An introduction to variation in American Sign Language. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 978-1563681448.

- Mitchell, Ross; Young, Travas; Bachleda, Bellamie; Karchmer, Michael (2006). «How Many People Use ASL in the United States?: Why Estimates Need Updating» (PDF). Sign Language Studies. 6 (3). ISSN 0302-1475. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Nyst, Victoria (2010), «Sign languages in West Africa», in Brentari, Diane (ed.), Sign Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 405–432, ISBN 978-0-521-88370-2

- Padden, Carol (2010), «Sign Language Geography», in Mathur, Gaurav; Napoli, Donna (eds.), Deaf Around the World (PDF), New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 19–37, ISBN 978-0199732531, archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2011, retrieved November 25, 2012

- Shaw, Emily; Delaporte, Yves (2015). A historical and etymological dictionary of American Sign Language : the origin and evolution of more than 500 signs. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 1-56368-622-8. OCLC 915119757.

- Solomon, Andrea (2010). Cultural and Sociolinguistic Features of the Black Deaf Community (Honors Thesis). Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- Supalla, Samuel; Cripps, Jody (2011). «Toward Universal Design in Reading Instruction» (PDF). Bilingual Basics. 12 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- Valli, Clayton; Lucas, Ceil (2000). Linguistics of American Sign Language. Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 978-1-56368-097-7. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- van der Hulst, Harry; Channon, Rachel (2010), «Notation systems», in Brentari, Diane (ed.), Sign Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–172, ISBN 978-0-521-88370-2

External links[edit]

- American Sign Language at Curlie

- Accessible American Sign Language vocabulary site

- American Sign Language discussion forum

- One-stop resource American Sign Language and video dictionary

- National Institute of Deafness ASL section

- National Association of the Deaf ASL information

- American Sign Language

- The American Sign Language Linguistics Research Project

- Video Dictionary of ASL

- American Sign Language Dictionary

Test Your American Sign Language By Taking A Free ASL Signs Quiz

Answer the questions and find out how well you know your American Sign Language signs

Start the Quiz. It’s Free!

Convenient, Fast and Free

You can take the quiz as many times as you want – a great way to practice!

The quiz is completely free! No credit card details required.

Flexible and convenient, the quiz works on any device.

Share your results on social media or by email. Invite your friends and see who scores the best.

Why take our Sign Language Signs Quiz?

Whether you choose to learn sign language for a loved one, your career or for the opportunity to integrate with the Deaf community; knowing ASL will give you an amazing new perspective of the world.

When you’re in the early stages of learning sign language and don’t know sign language signs, the sign language alphabet can help you spell out words and bridge the gap between you and the person you need to communicate with.

How it works

- Take the Quiz

Select and start the quiz. No need to create an account or provide credit card details – it’s free!

- Get your results After taking the quiz, you will receive your results by email. And for a small fee, get your own personal certificate!

- Share your results Let your boss know, invite your friends, post on social media… Show off your skills, it’s okay to brag!

Today I’m delighted to feature a guest post from Kristine about American Sign Language (ASL).

You’ll learn about:

- What ASL is and how it developed

- 5 common misconceptions people have about ASL

- Some similarities between ASL and English

- How learning ASL is different from learning English

Here’s Kristine…

What Is American Sign Language (ASL)?

ASL, short for American Sign Language, is the sign language most commonly used in, you guessed it, the United States and Canada.

Approximately 250,000 – 500,000 people of all ages throughout the US and Canada use this language to communicate as their native language. ASL is the third most commonly used language in the United States, after English and Spanish.

Contrary to popular belief, ASL is not representative of English nor is it some sort of imitation of spoken English that you and I use on a day-to-day basis. For many, it will come as a great surprise that ASL has more similarities to spoken Japanese and Navajo than to English.

When we discuss ASL or any other type of sign language, we are referring to what is called a visual-gestural language. The visual component refers to the use of body movements versus sound.

Because “listeners” must use their eyes to “receive” the information, this language was specifically created to be easily recognized by the eyes. The “gestural” component refers to the body movements or “signs” that are performed to convey a message.

A Brief History Of ASL

ASL is a relatively new language, which first appeared in the 1800s with the founding of the first successful American School for the Deaf by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet.

With strong roots in French Sign Language, ASL evolved to incorporate the signs students would use in less formal occasions such as in their home or within the deaf community.

As students graduated from the American School for the Deaf, some went on to open up their own schools, passing along this evolving American Sign Language as the contact language for the deaf in the United States.

Is There A Universal Sign Language?

There is no universal language for the deaf – all over the world, different sign languages have developed that vary from one another.

A spoken English speaker from the USA, for example, can generally understand someone from another English speaking nation such as England or Australia.

But with sign language, someone who signs using American Sign language would not be able to understand someone who signs using British Sign Language (BSL) or even Australian Auslan.

5 Common Misconceptions About ASL

Like any foreign language, ASL falls victim to many misconceptions among those who have not explored the language.

Because of the word ‘American’ in its name, many assume it shares the same qualities as English and is simply a representation of English using hands and gestures.

However, this is not the case. Let’s take a look at 5 of the most common misconceptions about ASL:

Misconception #1: ASL Is “English On The Hands”

As you’ve probably realised by now, ASL actually has little in common with spoken English, nor is it some sort of signed representation of English words.

ASL was formed independently of English and has its own unique sentence structure and symbols for various words and ideas.

The key features of ASL are:

- hand shape

- palm orientation

- hand movement

- hand location

- gestural features like facial expression and posture

When English is used through fingerspelling, hand motions represent the English alphabet to spell words in English, but this is not actually a part of ASL. Rather, it’s a separate element of signed communication.

Misconception #2: ASL Is Shorthand

Another common misconception about ASL is that it is some form of shorthand, or rapid communication by means of abbreviations and symbols.

This misconception arises due to the fact that ASL does not have a written component.

To call ASL shorthand is sorely incorrect, as ASL is a complex language system with its own set of linguistic components.

Misconception #3: ASL Is Most Like British Sign Language

Although the United States and the United Kingdom share spoken English as their predominant language, American Sign Language and British Sign Language vary greatly.

In fact, American Sign Language has its roots in French Sign Language, while British Sign Language has had a greater influence on the development of Australian Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language.

Misconception #4: ASL Is Finger Spelling

In ASL, fingerspelling is reserved for borrowing words from the English language for proper nouns and technical terms with no ASL equivalent.

For example, fingerspelling can be used for people’s names, places, titles, and brands.

When fingerspelling is used in ASL, it’s done using the American Fingerspelled Alphabet. This alphabet has 22 handshapes, that, when held in certain positions or movements represent the 26 letters of the English alphabet.

Misconception #5: Lip Reading Is An Effective Alternative To Learning Sign Language

It’s estimated that only 30% of English can be read on the lips by the deaf.

Lip reading is also not an effective because it’s a one-way method of communication.

It’s very unlikely that the speaker will be nearly as skilled at lip reading as those who are fluent in ASL, as learning to lip read well can take years upon years of practice.

This means that lip reading is not an effective method for two-way communication.

How Is Learning ASL Similar To Learning English?

Now that we’ve cleared up some of the misconceptions about ASL, let’s look at some of the similarities that ASL and English do share:

Both English And ASL Are Natural Languages

Both ASL and English are defined as “natural languages” meaning they were created and spread through people using them, without conscious planning or premeditation.

Artificial languages, on the other hand, are communication systems which have been consciously created or invented and do not develop and change naturally.

Some artificial systems that were invented for deaf children include:

- lip reading

- cued speech

- signed English

- manually coded English.

With any natural language, immersion is the surest way to ensure fluency and American Sign Language is no different.

This means surrounding yourself with the ASL/Deaf community to help expose yourself to the context, culture, behaviours, and grammatical rules of the language.

Both ASL And English Activate The Same Area Of The Brain

When an ASL signer sees and processes an ASL sentence, the same part of the brain – the left hemisphere – is activated as when an English speaker listens to or reads an English sentence.

This is because even though language exists in different forms, all of them are based on symbolic representation. These symbols can visual or aural but they are still processed in the same part of the brain.

Both Require Building Words To Form Sentences

Signed languages have similar grammatical characteristics as spoken languages.

Just as sounds are linked to form syllables and words in a spoken language, signs can be built through various gestures and hand shapes, positions, and movements.

ASL has the same basic set of word types as spoken English does, including nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, and adverbs.

How Is Learning ASL Different To Learning English?

In this article, I’ve compared many of the similarities between ASL and English, but how do the two differ for those trying to learn them?

Visual Language vs. Auditory Language

The first and most obvious difference between learning ASL and English is the medium you use for your learning – your eyes or your ears.

This may help to make ASL easier for people who are visual learners.

Similarly, if you are more of an auditory learner, you will probably find learning English or other spoken languages easier to pick up than sign language.

ASL Requires Gestural Movements Never Used In Spoken Language

Learning how to communicate through ASL and other sign languages requires a movement of body parts that most spoken-language speakers may not be used to.

These gestures include hand, arm, eye, and even facial expressions.

Just like the sounds of a new spoken language can take some getting used to for beginners, these gestures can be challenging for new learners of sign language to pick up.

ASL Is More Conceptual Than Spoken Languages

When making a connection between a sign and its intended meaning in ASL, it can be easier to comprehend the words meaning than in a spoken language.

For example, in ASL, the word book is signed with both hands gesturing the opening of a book.

The word “book” in English, however, does not conjure such an image. You either know what it means or you don’t and it’s hard to guess if you’re not sure.

Not all signs look like what they”re representing, but these conceptual connections are definitely more common than in spoken language.

ASL, because it’s visual, is a deeply conceptual language.

Because of this, the object of the sentence is signed first. For example, the English statement “The boy skipped home” would be reordered in ASL, starting with ‘home’ and then introducing the boy skipping.

ASL Has A Different Word Order Than English

As an English-speaker learning ASL, you may find the word order a bit tricky to get used to.

In ASL, how you assemble sentences following a different pattern, based on content.

When using indirect objects in ASL, you place the object right after the subject and then show the action. Lets look at an example:

- English: The boy throws a frisbee

- ASL: Boy — frisbee — throw

Tenses Are Represented Differently In ASL

In English, verbs are changed to show their tense, using the suffixes -ed, -ing and -s.

In ASL, tenses are shown differently.

Rather than conjugating the verbs, tense is established with a separate sign.

To represent the present tense, no change is made to the signs.

However, to sign past tense, you sign “finish” at chest level either before or after you finish your sentence.

Signing the future tense is quite similar to signing past tense. It’s indicated with a sign either before or at the end of the sentence as well as by adding “will” at the end of the sentence.

One interesting difference in the future tense, however, is that how far away from your body you sign the word “will” indicates how far in the future the sentence is.

As you can see, learning ASL is quite similar to learning any natural language.

Are You Thinking Of Learning ASL?

Every language has its own set of rules and grammar and ASL is no different.

While these rules and grammar are different are quite different from what we’re used to in English, they’re not particularly difficult to learn.

Like any language, getting the hang of ASL simply requires lots of practice and determination. You just need to get started.

If you’re currently thinking about learning a new language, you should consider giving ASL a try. I think you’ll find that it’s not only a fun and interesting language to learn but an incredibly enjoyable one too.

Are you interested in learning ASL or another form of sign language? Why do you want to learn sign language and what signs or topics do you most want to learn about? Let us know in the comments below!

This is a guest post by Kristine Thorndyke. Kristine is an English teacher who believes in improving lives through education. When shes not teaching, you can find her creating helpful resources for standardized testing at Test Prep Nerds.

Задание №6954.

Чтение. ЕГЭ по английскому

Прочитайте текст и запишите в поле ответа цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую выбранному Вами варианту ответа.

Показать текст. ⇓

Sign language like ASL is

1) a visual representation of a language.

2) a natural language in its own right.

3) an artificially developed system of signs.

4) a system of spelling words by hand gestures.

Решение:

Sign language like ASL is a natural language in its own right.

Язык жестов, такой как ASL, сам по себе является естественным языком.

«Sign language is a language that uses hand gestures that are modified by facial expressions.»

Показать ответ

Источник: Английский язык. Подготовка к ЕГЭ в 2021 году. Диагностические работы. Ватсон Е. Р.

Сообщить об ошибке

Тест с похожими заданиями

ОГЭ Английский язык задание №9 Демонстрационный вариант 2018 Прочитайте тексты и установите соответствие между текстами А–G и заголовками 1–8. В ответ запишите цифры, в порядке, соответствующем буквам. Используйте каждую цифру только один раз. В задании есть один лишний заголовок.

1. The scientific explanation

5. Places without rainbows

2. The real shape

6. A personal vision

3. A lucky sign

7. A bridge between worlds

4. Some tips

8. Impossible to catch

A. Two people never see the same rainbow. Each person sees a different one. It

happens because the raindrops are constantly moving so the rainbow is always

changing too. Each time you see a rainbow it is unique and it will never be the

same! In addition, everyone sees colours differently according to the light and

how their eyes interpret it.

B. A rainbow is an optical phenomenon that is seen in the atmosphere. It appears

in the sky when the sun’s light is reflected by the raindrops. A rainbow always

appears during or immediately after showers when the sun is shining and the

air contains raindrops. As a result, a spectrum of colours is seen in the sky. It

takes the shape of a multicoloured arc.

C. Many cultures see the rainbow as a road, a connection between earth and

heaven (the place where God lives). Legends say that it goes below the earth at

the horizon and then comes back up again. In this way it makes a permanent

link between what is above and below, between life and death. In some myths

the rainbow is compared to a staircase connecting earth to heaven.

D. We all believe that the rainbow is arch-shaped. The funny thing is that it’s

actually a circle. The reason we don’t see the other half of the rainbow is

because we cannot see below the horizon. However, the higher we are above

the ground, the more of the rainbow’s circle we can see. That is why, from an

airplane in flight, a rainbow will appear as a complete circle with the shadow of

the airplane in the centre.

E. In many cultures there is a belief that seeing a rainbow is good. Legends say

that if you dig at the end of a rainbow, you’ll find a pot of gold. Rainbows are

also seen after a storm, showing that the weather is getting better, and there is

hope after the storm. This is why they are associated with rescue and good

fortune. If people happen to get married on such a day, it is said that they will

enjoy a very happy life together.

F. You can never reach the end of a rainbow. A rainbow is all light and water. It is

always in front of you while your back is to the sun. As you move, the rainbow

that your eye sees moves as well and it will always ‘move away’ at the same

speed that you are moving. No matter how hard you try, a rainbow will always

be as far away from you as it was before you started to move towards it.

G. To see a rainbow you have to remember some points. First, you should be

standing with the sun behind you. Secondly, the rain should be in front of you.

The most impressive rainbows appear when half of the sky is still dark with

clouds and the other half is clear. The best time to see a rainbow is on a warm

day in the early morning after sunrise or late afternoon before sunset. Rainbows

are often seen near waterfalls and fountains.

Запишите в таблицу выбранные цифры под соответствующими буквами.

| Текст | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Заголовок |

ОГЭ Английский язык задание №9 Демонстрационный вариант 2017

1. Traditional delivery 2. Loss of popularity 3. Money above privacy

4. The best-known newspapers 5. Focus on different readers 6. The successful competitor

7. Size makes a difference 8. Weekend reading

A. As in many other European countries, Britain’s main newspapers are losing their readers. Fewer and fewer people are buying broadsheets and tabloids at the newsagent’s. In the last quarter of the twentieth century people became richer and now they can choose other forms of leisure activity. Also, there is the Internet which is a convenient and inexpensive alternative source of news.

B. The ‘Sunday papers’ are so called because that is the only day on which they are published. Sunday papers are usually thicker than the dailies and many of them have six or more sections. Some of them are ‘sisters’ of the daily newspapers. It means they are published by the same company but not on week days.

C. Another proof of the importance of ‘the papers’ is the morning ‘paper round’. Most newsagents organise these. It has become common that more than half of the country’s readers get their morning paper brought to their door by a teenager. The boy or girl usually gets up at around 5:30 a.m. every day including Sunday to earn a bit of pocket money.

D. The quality papers or broadsheets are for the better educated readers. They devote much space to politics and other ‘serious’ news. The popular papers, or tabloids, sell to a much larger readership. They contain less text and a lot more pictures. They use bigger headlines and write in a simpler style of English. They concentrate on ‘human interest stories’ which often means scandal.

E. Not so long ago in Britain if you saw someone reading a newspaper you could tell what kind it was without even checking the name. It was because the quality papers were printed on very large pages called ‘broadsheet’. You had to have expert turning skills to be able to read more than one page. The tabloids were printed on much smaller pages which were much easier to turn.

F. The desire to attract more readers has meant that in the twentieth century sometimes even the broadsheets in Britain look rather ‘popular’. They give a lot of coverage to scandal and details of people’s private lives. The reason is simple. What matters most for all newspaper publishers is making a profit. They would do anything to sell more copies.

G. If you go into any newsagent’s shop in Britain you will not find only newspapers. You will also see rows and rows of magazines for almost every imaginable taste. There are specialist magazines for many popular pastimes. There are around 3,000 of them published in the country and they are widely read, especially by women. Magazines usually list all the TV and radio programmes for the coming week and many British readers prefer them to newspapers.

| Текст | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Заголовок |

1.Living through ages 2. Influenced by fashion 3. Young and energetic

4. Old and beautiful 5. Still a mystery 6. A lot to see and to do

7. Welcome to students 8. Fine scenery

A. Ireland is situated on the western edge of Europe. It is an island of great beauty with rugged mountains, blue lakes, ancient castles, long sandy beaches and picturesque harbors. The climate is mild and temperate throughout the year. Ireland enjoys one of the cleanest environments in Europe. Its unspoilt countryside provides such leisure ac¬tivities as hiking, cycling, golfing and horse-riding.

B. Over the past two decades, Ireland has become one of the top destinations for En¬glish language learning — more than 100,000 visitors come to Ireland every year to study English. One quarter of Ireland’s population is under 25 years of age and Dublin acts as a magnet for young people looking for quality education. The Irish are relaxed, friendly, spontaneous, hospitable people and have a great love of conversation. So, there is no better way of learning a language than to learn it in the country where it is spoken.

C. Dublin sits in a vast natural harbor. Such a protected harbor appealed to the first settlers 5,000 years ago and traces of their culture have been found around Dublin and its coast. But it was not until the Vikings came sailing down the coast in the middle 9th cen¬tury that Dublin became an important town. Next to arrive were the Anglo-Norman ad¬venturers. This was the beginning of the long process of colonization that dictated Ire¬land’s development over the next seven hundred years.

D. Now Dublin is changing fast and partly it ’s thanks to its youthful population over 50 percent are under the age of twenty-five and that makes the city come alive. To¬day Dublin is a city full of charm with a dynamic cultural life, small enough to be friend¬ly, yet cosmopolitan in outlook. This is the culture where the heritage of ancient days brings past and present together.

E. In general, cultural life of Dublin is very rich and you can enjoy visiting different museums, art galleries and exhibitions. But for those looking for peace and quiet there are two public parks in the centre of the city: St. Stephen’s Green and Merrion Square.

The city centre has several great shopping areas depending on your budget as well as nu¬merous parks and green areas for relaxing in. Dublin is also a sports-m ad city and wheth¬er you are playing or watching, it has everything for the sports enthusiast.

F. Step dances are the creation of Irish dancing m asters of the late 18th century.

Dancing m asters would often travel from town to town, teaching basic dancing steps to those interested and able to pay for them . Their appearance was motivated by a desire to learn the ‘fashionable’ dance styles which were coming from France. The dance m asters often changed these dances to fit the traditional music and, in doing so, laid the basis for much of today’s traditional Irish dance — ceili, step, and set.

G. St Patrick is known as the patron saint of Ireland. True, he was not a born Irish.

But he has become an integral part of the Irish heritage, mostly through his service across Ireland of the 5th century. Patrick was born in the second half of the 4th century AD. There are different views about the exact year and place of his birth . According to one school of opinion, he was born about 390 A.D., while the other school says it is about 373 AD. Again, his birth place is said to be in either Scotland or Roman England. So, though Patricius was his Romanicized name, he became later known as Patrick.

Запишите в таблицу выбранные цифры под соответствующими буквами.

| Текст | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Заголовок |

Источник: ОГЭ 2017 АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ЯЗЫК Л.М.Гудкова О.В.Терентьева

1.Thanks to new technology 2. A custom for a sweet-tooth 3. The upside down world

4. Nice for people in love 5. Happy next year 6. Not allowed for some time

7. Watch out or give the money 8. Christmas is coming

A. Houses are decorated with colored paper ribbons and chains. Holly with red ber¬ries is put on the walls and looks very colorful. A piece of mistletoe (a plant) is hung from the ceiling. It is said to be lucky to kiss under the mistletoe hanging from the ceil¬ing. As you can understand, a lot of people who may not usually kiss each other take the chance given by a piece of mistletoe!

B. One of the delicacies the British have enjoyed for almost 900 years is the mince pie.