1. INTROITUS

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine,

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Te decet hymnus, Deus, in Sion,

Et tibi reddetur votum in Jerusalem;

Exaudi orationem meam,

Ad te omnis caro veniet.

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine,

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

(перевод)

Покой вечный даруй им, Господи,

И свет вечный да светит им.

Тебе поется гимн, Боже, в Сионе,

И Тебе возносятся молитвы в Иерусалиме.

Услышь моление мое,

К Тебе возвращается всякая плоть.

Покой вечный даруй им, Господи,

И свет вечный да светит им.

2. KYRIE

Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison,

Kyrie eleison.

(перевод)

Господи, помилуй. Христос, помилуй;

Господи, помилуй.

3. SEQUENTIA

Dies irae

Dies irae, dies illa

Solvet saeclum in favilla,

Teste David cum Sibylla.

Quantus tremor est futurus,

Quando judex est venturus,

Cuncta stricte discussurus.

(перевод)

День гнева, тот день

Превратит мир в прах,

По свидетельству Давида и Сивиллы.

Сколь великий трепет настанет,

Когда придет Судия,

Который строго всё рассудит.

4. Tuba mirum

Tuba mirum spargens sonum

Per sepulcra regionum,

Coget omnes ante thronum.

Mors stupebit et natura,

Cum resurget creatura,

Judicanti responsura.

Liber scriptus proferetur,

In quo totum continetur,

Unde mundus judicetur.

Judex ergo cum sedebit,

Quidquid latet apparebit,

Nil inultum remanebit.

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus?

quem patronum rogaturus,

cum vix justus sit securus?

(перевод)

Трубы удивительный звук пронесется

Над кладбищенскими странами,

Созывая всех к престолу.

Смерть и природа замрут,

Когда творение воскреснет, чтобы

Судящему дать ответ.

Откроется книга,

Содержащая в себе всё,

По чему судим будет мир.

И вот, когда Судия воссядет,

Все тайное станет явным,

Ничто не останется безнаказанным.

Что тогда, несчастный, я скажу?

Кого призову в защитники,

если и праведник едва будет в безопасности?

5. Rex tremendae

Rex tremendae majestatis,

Qui salvandos salvas gratis,

Salva me, fons pietatis.

(перевод)

Царь ужасающего величия,

Благосклонно спасающий ищущих спасения,

Спаси меня, источник милосердия.

6. Recordare

Recordare, Jesu pie,

Quod sum causa tuae viae,

Ne me perdas illa die.

Quaerens me sedisti lassus,

Redemisti crucem passus;

Tantus labor non sit cassus.

Juste judex ultionis,

Donum fac remissionis

Ante diem rationis.

Ingemisco tanquam reus,

Culpa rubet vultus meus;

Supplicanti parce, Deus.

Qui Mariam absolvisti,

Et latronem exaudisti,

Mihi quoque spem dedisti.

Preces meae non sum dignae,

Sed tu, bonus, fac benigne,

Ne perenni cremer igne.

Inter oves locum praesta,

Et ab haedis me sequestra,

Statuens in parte dextra.

(перевод)

Вспомни, Иисусе милосердный,

Что я был причиной Твоего пути,

Не погуби меня в тот день.

Меня, сидящего в унынии,

Искупил, приняв муку на кресте;

Да не будет жертва бесплодной.

Праведный Судия отмщения,

Даруй прощение

Перед днем Суда

Виновный, со стоном взываю,

С пылающим от стыда лицом;

Пощади умоляющего, Боже.

Оправдавший Марию

И разбойника услышавший,

Мне тоже дай надежду.

Мольбы мои недостойны,

Но Ты, Благой, сделай милость,

Не дай мне вечно гореть в огне.

Среди агнцев дай место,

И от козлищ меня отдели,

Поставив на правую сторону.

7. Confutatis

Confutatis maledictis,

Flammis acribus addictis,

Voca me cum benedictis.

Oro supplex et acclinis,

Cor contritum quasi cinis,

Gere curam mei finis.

(перевод)

Посрамив нечестивых,

Пламени предав их адскому,

Призови меня с благословенными.

Молю смиренный и преклоненный,

Сердце истертое словно пепел.

Позаботься о моей кончине.

8. Lacrimosa

Lacrimosa dies illa,

Qua resurget ex favilla

Judicandus homo reus.

Huic ergo parce, Deus,

Pie Jesu Domine,

Dona eis requiem. Amen.

(перевод)

Полон слез тот день,

Когда восстанет из праха

Чтобы быть осужденным, человек.

Так пощади его, Боже,

Милостивый Господи Иисусе,

Даруй им покой. Аминь.

9. OFFERTORIUM

Domine Jesu Christe

Domine Jesu Christe, Rex gloriae,

Libera animas omnium fidelium defunctorum

De poenis inferni et de profundo lacu.

Libera eas de ore leonis,

Ne absorbeat eas tartarus,

Ne cadant in obscurum:

Sed signifer sanctus Michael

Repraesentet eas in lucem sanctam,

Quam olim Abrahae promisisti,

Et semini ejus.

(перевод)

Господи Иисус Христос, Царь славы,

Освободи души всех верных усопших

От мук ада и бездонного озера.

Освободи их от пасти льва,

Дабы не поглотил их тартар,

И не пропали они во мгле:

Но предводитель святой Михаил

Да введет их в священный свет,

Который Ты некогда Аврааму обещал

И потомству его.

10. Hostias

Hostias et preces tibi, Domine,

Laudis offerimus.

Tu suscipe pro animabus illis,

Quarum hodie memoriam facimus:

Fac eas, Domine,

De morte transire ad vitam,

Quam olim Abrahae promisisti,

Et semini ejus.

(перевод)

Жертвы и мольбы Тебе, Господи,

С хвалою возносим.

Прими их ради душ тех,

О ком мы сегодня вспоминаем:

Позволь им, Господи,

От смерти перейти к жизни,

Которую Ты некогда Аврааму обещал

И потомству его.

11. SANCTUS

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus,

Dominus Deus Sabaoth!

Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua.

Hosanna in excelsis.

(перевод)

Свят, Свят, Свят,

Господь Бог Саваоф!

Полны небеса и земля славой Твоей.

Осанна в вышних.

12. BENEDICTUS

Benedictus, qui venit in nomine Domini.

Hosanna in excelsis.

(перевод)

Благословен, грядый во имя Господня.

Осанна в вышних.

13. AGNUS DEI

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi,

Dona eis requiem.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi,

Dona eis requiem sempiternam.

(перевод)

Агнец Божий, кто принял на себя грехи мира.

Даруй им покой.

Агнец Божий, кто принял на себя грехи мира.

Даруй им вечный покой.

14. COMMUNIO

Lux aeterna

Lux aeterna luceat eis, Domine,

Cum sanctis tuis in aeternum, quia pius es.

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine,

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

(перевод)

Да светит им вечный свет, Господи,

Со святыми Твоими вечно, ибо Ты многомилостив.

Покой вечный даруй им, Господи,

И вечный свет да светит им[4].

Template:Infobox musical composition

The Requiem in D minor, K. 626, is a requiem mass by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart composed part of the Requiem in Vienna in late 1791, but it was unfinished at his death on 5 December the same year. A completed version dated 1792 by Franz Xaver Süssmayr was delivered to Count Franz von Walsegg, who commissioned the piece for a Requiem service to commemorate the anniversary of his wife’s death on 14 February.

The autograph manuscript shows the finished and orchestrated Introit in Mozart’s hand, and detailed drafts of the Kyrie and the sequence Dies Irae as far as the first eight bars of the «Lacrymosa» movement, and the Offertory. It cannot be shown to what extent Süssmayr may have depended on now lost «scraps of paper» for the remainder; he later claimed the Sanctus and Agnus Dei as his own. Walsegg probably intended to pass the Requiem off as his own composition, as he is known to have done with other works. This plan was frustrated by a public benefit performance for Mozart’s widow Constanze. She was responsible for a number of stories surrounding the composition of the work, including the claims that Mozart received the commission from a mysterious messenger who did not reveal the commissioner’s identity, and that Mozart came to believe that he was writing the requiem for his own funeral.

The Requiem is scored for 2 basset horns in F, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets in D, 3 trombones (alto, tenor & bass), timpani (2 drums), violins, viola and basso continuo (cello, double bass, and organ). The vocal forces include soprano, contralto, tenor, and bass soloists and an SATB mixed choir.

Structure

Süssmayr’s completion divides the Requiem into fourteen movements:

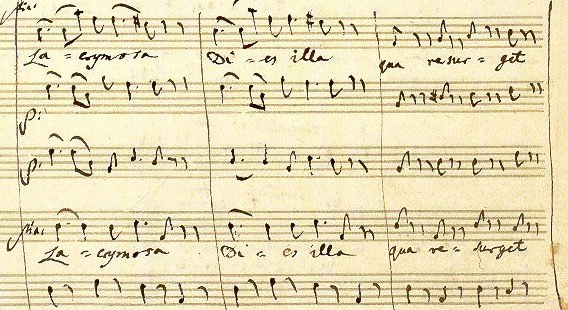

File:Manuscript of the last page of Requiem.jpg Bars 1–5 of the Lacrymosa

- I. Introitus

- Requiem (choir and soprano solo) (D minor)

- II. Kyrie (choir) (D minor)

- III. Sequentia (text based on sections of the Dies Irae)

- Dies irae (choir) (D minor)

- Tuba mirum (soprano, contralto, tenor and bass solo) (B-flat major)

- Rex tremendae (choir) (G minor–D minor)

- Recordare (soprano, contralto, tenor and bass solo) (F major)

- Confutatis (choir) (A minor–F major, last chord V of D minor)

- Lacrymosa (choir) (D minor)

- IV. Offertorium

- Domine Jesu (choir with solo quartet) (G minor)

- Hostias (choir) (E-flat major–G minor)

- V. Sanctus (choir) (D major)

- VI. Benedictus (solo quartet and choir) (B-flat major)

- VII. Agnus Dei (choir) (D minor–B-flat major)

- VIII. Communio

- Lux aeterna (soprano solo and choir) (B-flat major–D minor)

All sections from the Sanctus onwards are not present in Mozart’s manuscript fragment. Mozart may have intended to include the Amen fugue at the end of the Sequentia, but Süssmayr did not do so in his completion.

The Introitus is in D minor and finishes on a half-cadence that transitions directly into Kyrie. The Kyrie is a double fugue, with one subject setting the words «Kyrie eleison» and the other «Christe eleison«. The movement Tuba mirum opens with a trombone solo accompanying the bass. The Confutatis is well known for its string accompaniment; it opens with agitated figures that accentuate the wrathful sound of the basses and tenors, but it turns into soft arpeggios in the second phrase while accompanying the soft sounds of the sopranos and altos.

Details

The following table shows for the eight movements in Süssmayr’s completion with their subdivisions the title and incipit, the type of movement, the vocal parts soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T) and bass (B) and four-part choir SATB, the tempo, key and time.

Template:Classical movement header

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

|}

History

Composition

At the time of Mozart’s death on 5 December 1791, only the first two movements «Requiem aeternam» and «Kyrie» were completed in all of the orchestral and vocal parts. The «Sequence» and the «Offertorium» were completed in skeleton, with the exception of the «Lacrymosa», which breaks off after the first eight bars. The vocal parts and the continuo were fully notated. Occasionally, some of the prominent orchestral parts were briefly indicated, such as the first violin part of the Rex tremendae and Confutatis, the musical bridges in the Recordare, and the trombone solos of the «Tuba Mirum». What remained to be completed for these sections were mostly accompanimental figures, inner harmonies, and orchestral doublings to the vocal parts.

Constanze Mozart and the Requiem after Mozart’s death

The eccentric count Franz von Walsegg commissioned the Requiem from Mozart anonymously through intermediaries. The count, an amateur chamber musician who routinely commissioned works by composers and passed them off as his own,[1][2] wanted a Requiem Mass he could claim he composed to memorialize the recent passing of his wife. Mozart received only half of the payment in advance, so upon his death his widow Constanze was keen to have the work completed secretly by someone else, submit it to the count as having been completed by Mozart and collect the final payment.[3] Joseph von Eybler was one of the first composers to be asked to complete the score, and had worked on the movements from the Dies irae up until the Lacrymosa. In addition, a striking similarity between the openings of the Domine Jesu Christe movements in the requiems of the two composers suggests that Eybler at least looked at later sections.Template:Explain After this work, he felt unable to complete the remainder, and gave the manuscript back to Constanze Mozart.

The task was then given to another composer, Franz Xaver Süssmayr. Süssmayr borrowed some of Eybler’s work in making his completion, and added his own orchestration to the movements from the Kyrie onward, completed the Lacrymosa, and added several new movements which a Requiem would normally comprise: Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei. He then added a final section, Lux aeterna by adapting the opening two movements which Mozart had written to the different words which finish the Requiem mass, which according to both Süssmayr and Mozart’s wife was done according to Mozart’s directions. Some people consider it unlikely, however, that Mozart would have repeated the opening two sections if he had survived to finish the work.

Other composers may have helped Süssmayr. The Agnus Dei is suspected by some scholars[4] to have been based on instruction or sketches from Mozart because of its similarity to a section from the Gloria of a previous mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220) by Mozart,[5] as was first pointed out by Richard Maunder. Others have pointed out that in the beginning of the Agnus Dei the choral bass quotes the main theme from the Introitus.[6] Many of the arguments dealing with this matter, though, center on the perception that if part of the work is high quality, it must have been written by Mozart (or from sketches), and if part of the work contains errors and faults, it must have been all Süssmayr’s doing.[citation needed]

Another controversy is the suggestion (originating from a letter written by Constanze) that Mozart left explicit instructions for the completion of the Requiem on «little scraps of paper.» The extent to which Süssmayr’s work may have been influenced by these «scraps» if they existed at all remains a subject of speculation amongst musicologists to this day.

The completed score, initially by Mozart but largely finished by Süssmayr, was then dispatched to Count Walsegg complete with a counterfeited signature of Mozart and dated 1792. The various complete and incomplete manuscripts eventually turned up in the 19th century, but many of the figures involved left ambiguous statements on record as to how they were involved in the affair. Despite the controversy over how much of the music is actually Mozart’s, the commonly performed Süssmayr version has become widely accepted by the public. This acceptance is quite strong, even when alternative completions provide logical and compelling solutions for the work.

The confusion surrounding the circumstances of the Requiem’s composition was created in a large part by Mozart’s wife, Constanze[citation needed]. Constanze had a difficult task in front of her: she had to keep secret the fact that the Requiem was unfinished at Mozart’s death, so she could collect the final payment from the commission. For a period of time, she also needed to keep secret the fact that Süssmayr had anything to do with the composition of the Requiem at all, in order to allow Count Walsegg the impression that Mozart wrote the work entirely himself. Once she received the commission, she needed to carefully promote the work as Mozart’s so that she could continue to receive revenue from the work’s publication and performance. During this phase of the Requiem’s history, it was still important that the public accept that Mozart wrote the whole piece, as it would fetch larger sums from publishers and the public if it were completely by Mozart.

It is Constanze’s efforts that created the flurry of half-truths and myths almost instantly after Mozart’s death. According to Constanze, Mozart declared that he was composing the Requiem for himself, and that he had been poisoned. His symptoms worsened, and he began to complain about the painful swelling of his body and high fever. Nevertheless, Mozart continued his work on the Requiem, and even on the last day of his life, he was explaining to his assistant how he intended to finish the Requiem. Source materials written soon after Mozart’s death contain serious discrepancies, which leave a level of subjectivity when assembling the «facts» about Mozart’s composition of the Requiem. For example, at least three of the conflicting sources, both dated within two decades following Mozart’s death, cite Constanze as their primary source of interview information. In 1798, Friedrich Rochlitz, a German biographical author and amateur composer, published a set of Mozart anecdotes that he claimed to have collected during his meeting with Constanze in 1796.[7]

The Rochlitz publication makes the following statements:

- Mozart was unaware of his commissioner’s identity at the time he accepted the project.

- He was not bound to any date of completion of the work.

- He stated that it would take him around four weeks to complete.

- He requested, and received, 100 ducats at the time of the first commissioning message.

- He began the project immediately after receiving the commission.

- His health was poor from the outset; he fainted multiple times while working.

- He took a break from writing the work to visit the Prater with his wife.

- He shared the thought with his wife that he was writing this piece for his own funeral.

- He spoke of «very strange thoughts» regarding the unpredicted appearance and commission of this unknown man.

- He noted that the departure of Leopold II to Prague for the coronation was approaching.

The most highly disputed of these claims is the last one, the chronology of this setting. According to Rochlitz, the messenger arrives quite some time before the departure of Leopold for the coronation, yet there is a record of his departure occurring in mid-July 1791. However, as Constanze was in Baden during all of June to mid-July, she would not have been present for the commission or the drive they were said to have taken together.[7] Furthermore, The Magic Flute (except for the Overture and March of the Priests) was completed by mid-July. La clemenza di Tito was commissioned by mid-July.[7] There was no time for Mozart to work on the Requiem on the large scale indicated by the Rochlitz publication in the time frame provided.

Also in 1798, Constanze is noted to have given another interview to Franz Xaver Niemetschek,[8] another biographer looking to publish a compendium of Mozart’s life. He published his biography in 1808, containing a number of claims about Mozart’s receipt of the Requiem commission:

- Mozart received the commission very shortly before the Coronation of Emperor Leopold II, and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee, but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

- He fell ill while writing the work

- He told Constanze «I am only too conscious…my end will not be long in coming: for sure, someone has poisoned me! I cannot rid my mind of this thought.»

- Constanze thought that the Requiem was overstraining him; she called the doctor and took away the score.

- On the day of his death he had the score brought to his bed.

- The messenger took the unfinished Requiem soon after Mozart’s death.

- Constanze never learned the commissioner’s name.

This account, too, has fallen under scrutiny and criticism of its accuracy. According to letters, Constanze most certainly knew the name of the commissioner by the time this interview was released in 1800.[8] Additionally, the Requiem was not given to the messenger until some time after Mozart’s death.[7] This interview contains the only account from Constanze herself of the claim that she took the Requiem away from Wolfgang for a significant duration during his composition of it.[7] Otherwise, the timeline provided in this account is historically probable. However, the most highly accepted text attributed to Constanze is the interview to her second husband, Georg Nikolaus von Nissen.[7] After Nissen’s death in 1826, Constanze released the biography of Wolfgang (1828) that Nissen had compiled, which included this interview. Nissen states:

- Mozart received the commission shortly before the coronation of Emperor Leopold and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee, but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

The Nissen publication lacks information following Mozart’s return from Prague.[7]

Modern completions

Template:Refimprove section

In the 1960s a sketch for an Amen fugue was discovered, which some musicologists (Levin, Maunder) believe belongs to the Requiem at the conclusion of the sequence after the Lacrymosa. H. C. Robbins Landon argues that this Amen fugue was not intended for the Requiem, rather that it «may have been for a separate unfinished mass in D minor» to which the Kyrie K. 341 also belonged. There is, however, compelling evidence placing the «Amen Fugue» in the Requiem[9] based on current Mozart scholarship. First, the principal subject is the main theme of the requiem (stated at the beginning, and throughout the work) in strict inversion. Second, it is found on the same page as a sketch for the Rex tremendae (together with a sketch for the overture of his last opera The Magic Flute), and thus surely dates from late 1791. The only place where the word ‘Amen’ occurs in anything that Mozart wrote in late 1791 is in the sequence of the Requiem. Third, as Levin points out in the foreword to his completion of the Requiem, the addition of the Amen Fugue at the end of the sequence results in an overall design that ends each large section with a fugue.

Since the 1970s several composers and musicologists, dissatisfied with the traditional «Süssmayr» completion, have attempted alternative completions of the Requiem. Each version follows a distinct methodology for completion:

- Franz Beyer – makes revisions to Süssmayr‘s orchestration in an attempt to create a more Mozartian style and makes a few minor changes to Süssmayr’s sections (i.e. lengthening the Osanna fugue slightly for a more conclusive sounding ending).

- H. C. Robbins Landon – orchestrates parts of the completion using the partial work by Eybler, thinking that Eybler’s work is a more reliable guide of Mozart’s intentions.

- Richard Maunder – dispenses completely with the parts known to be written by Süssmayr, but retains the Agnus Dei after discovering an extensive paraphrase from an earlier mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220). Recomposes the Lacrymosa from bar 9 onwards, and includes a completion of the Amen fugue.

- Duncan Druce – makes slight changes in orchestration, but retains Eybler’s ninth and tenth measures of the Lacrymosa, lengthening the movement substantially to end in the «Amen Fugue». He also completely rewrites the Benedictus, only retaining the opening theme.

- Robert D. Levin and Simon Andrews – each retain the structure of Süssmayr while adjusting orchestration, voice leading and in some cases rewriting entire sections in an effort to make the work more Mozartean.

- Pánczél Tamás – makes revisions to Süssmayr’s score in a manner similar to Beyer, but extends the Lacrymosa significantly past Süssmayr’s passages and rewrites the Benedictus’s ending leading into the Osanna reprise.

- Clemens Kemme – orchestration rewritten in a style closer to Eybler’s, emphasing the basset horns in particular, with a reworked Sanctus, Benedictus and extended Osanna fugue.

- Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs – provides an entirely new instrumentation, based on Eybler’s ideas, new elaborations of the Amen and Osanna fugues, and a new continuity of the Lacrymosa (after b. 18), Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei, following those bars of which Dr. Cohrs assumes Mozart might have sketched himself.

- Masaaki Suzuki – follows a methodology similar to Robbins Landon, but with further stylistic elaboration on Süssmayr’s sections.

- Marius Flothuis – revision of Süssmayr’s version via removal of vocal doubling, rewriting of the trombone parts and the harmonic transition to the Osanna reprise in the Benedictus.

- Timothy Jones – reworking of the Lacrymosa, composition of an extensive Amen fugue modeled on the ‘Cum sancto spiritu’ fugue from the Great Mass in C minor, K. 427, and a long elaboration on Süssmayr’s Osanna fugue.

- Michael Finnissy – takes the Süssmayr completion as its basis and adheres to Mozart’s scoring. Of the five movements newly completed by Finnissy the ‘Lacrymosa’ has been written in Mozartian style while the four final movements represent an exploration of musical styles since Mozart’s death in 1791.

- Knud Vad – follows Süssmayr’s completion until the Sanctus and Benedictus which are noticeably rewritten in places (i.e. Osanna turned into a double fugue played adagio)

- Gregory Spears – includes a new “Sanctus,” “Benedictus” and “Agnus Dei” designed to replace the Süssmayr completion of those movements. Spears’s completion recognizes the juxtaposition of old and new sources common in liturgical music of the period, and incorporates two cadential fragments from Süssmayr’s completion into the end of his “Benedictus” and “Agnus Dei”.

- Letho Kostoglou (Australian musicologist) – utilises primarily music composed by Mozart. It was performed at Adelaide Town Hall on 4 September 2010. This edition was endorsed by Richard Bonynge and Patrick Thomas.

- Pierre-Henri Dutron‘s edits are largely a revision of Süssmayr’s version. Sanctus and Benedictus significantly rewritten from opening themes onward. Creative liberties are taken with regard to the dispersion of the vocal material between the chorus and soloists. This version was used by conductor René Jacobs for his performances given at the end of 2016.

In the Levin, Andrews, Druce and Cohrs versions, the Sanctus fugue is completely rewritten and re-proportioned and the Benedictus is restructured to allow for a reprise of the Sanctus fugue in the key of D (rather than Süssmayr’s use of B-flat).

Maunder, Levin, Druce, Suzuki, Tamás, Cohrs and Jones use the sketch for the Amen fugue discovered in the 1960s to compose a longer and more substantial setting to the words «Amen» at the end of the sequence. In the Süssmayr version, «Amen» is set as a plagal cadence with a Picardy third (iv–I in D minor) at the end of the Lacrymosa: the Andrews version uses the Süssmayr ending. Jones combines the two, ending his Amen fugue with a variation on the concluding bars of Süssmayr’s Lacrymosa as well as the aforementioned plagal cadence.

Supplementary works by other composers

For a performance of the Requiem in Rio de Janeiro in December 1819, Austrian composer Sigismund von Neukomm constructed a further movement based on material in the Süssmayr version. Incorporating music from various movements including the Requiem aeternum, Dies irae, Lacrymosa and Agnus Dei, the bulk of the piece is set to the Libera me, a responsory text which is traditionally sung after the Requiem mass, and concludes with a reprise of the Kyrie and a final Requiescat in pace. A contemporary of Neukomm and a pupil of Mozart’s, Ignaz von Seyfried would compose his own Mozart-inspired Libera me for a performance at Ludwig van Beethoven‘s funeral in 1827.

Timeline

Template:Refimprove section

Before 1791

- 2 January 1772: Mozart participates in the premiere of Michael Haydn‘s Requiem in C minor.[10]

- 21 September 1784: Birth of Mozart’s older son, Karl Thomas Mozart.

- 20 April 1789: Mozart visits Leipzig where he studied works by Bach.[11]

- December 1790: Mozart completes his string quintet in D (K. 593) and the Adagio and Allegro in F minor for a mechanical organ (K. 594). These are his first works in a new burst of creativity after a very low production of works in 1790.

1791

- 5 January: Mozart completes his last piano concerto, in B-flat (K. 595).

- 14 January: Mozart completes three German songs (K. 596–8).

- January–March: Mozart composes mostly dance music (K. 599–611).

- 14 February: Anna, Count von Walsegg’s wife, dies at the age of 20.

- 3 March: Mozart completes the Fantasia in F minor for a mechanical organ (K. 608).

- 8 March: Mozart completes the bass aria Per questa bella mano (K. 612).

- March: Mozart completes the Variations in F on «Ein Weib ist das herrlichste Ding» (K. 613).

- 12 April: Mozart completes his last string quintet, in E-flat (K. 614).

- May 4: Mozart completes the Andante in F for a small mechanical organ (K. 616).

- 23 May: Mozart completes the Adagio and Rondo for glass harmonica, flute, oboe, viola and cello, his last chamber work (K. 617).

- 17 June: Mozart completes the motet Ave verum corpus (K. 618).

- July: Mozart completes the cantata Die ihr des unermeßlichen Weltalls (K. 619).

- mid-July: A messenger (probably Franz Anton Leitgeb, the count’s steward) arrives with note asking Mozart to write a Requiem mass.

- mid-July: Commission from Domenico Guardasoni, impresario of the Prague National Theatre to compose the opera, La clemenza di Tito (K. 621), for the festivities surrounding the coronation on September 6 of Leopold II as King of Bohemia.

- 26 July: Birth of Mozart’s younger son, Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart.

- August: Mozart works mainly on La clemenza di Tito; completed by September 5.

- 25 August: Mozart leaves for Prague.

- 6 September: Mozart conducts premiere of La clemenza di Tito.

- mid-September – 28 September: Revision and completion of The Magic Flute (K. 620).

- 30 September: Premiere of The Magic Flute.

- 7 October: Mozart completes Clarinet Concerto in A major (K. 622).

- 8 October – 20 November: Mozart works on the Requiem and a cantata (K. 623).

- 15 November: Mozart completes the cantata.

- 20 November: Mozart is confined to bed due to his illness.

- 5 December: Mozart dies shortly after midnight.

- 7 December: Burial in St. Marx Cemetery.

- 5 December through 10 December: Kyrie from Requiem completed by unknown composer (once identified as Mozart’s pupil Franz Jakob Freystädtler, although this attribution is not generally accepted now)

- 10 December: Requiem (probably only Introitus and Kyrie) were performed in St. Michael’s Church, Vienna, for a memorial for Mozart by the staff of the Theater auf der Wieden.

- 21 December: Joseph Leopold Eybler receives score of Requiem from Constanze, promising to complete it by mid-Lent (mid-March) of next year. He later gives up and returns the score to Constanze, who turns it to Süssmayr to complete.

After 1791

- Early March 1792: probably the time Süssmayr finished the Requiem

- 2 January 1793: Performance of Requiem for Constanze’s benefit arranged by Gottfried van Swieten

- Early December 1793: Requiem delivered to the Count

- 14 December 1793: Requiem performed in memory of the count’s wife in the church at Wiener-Neustadt[citation needed]

- 14 February 1794: Requiem performed again in Patronat Church Maria Schutz [de] in Semmering

- 1799: Breitkopf & Härtel published the Requiem.

- 1800 or later: Walsegg receives leaves 1 through 10 of the autograph (Introitus and Kyrie)

- Autumn 1800: Abbé Maximilian Stadler compares all known manuscript copies (including Walsegg’s) and editions of the score, and noted down copying errors and determined precisely which parts of the Requiem were written by Mozart.

- After 1802: Abbé Stadler receives leaves 11 through 32 (Dies irae to Confutatis) of Mozart’s Requiem autograph from Constanze. Later Eybler would receive leaves 33 to 46, the Lacrymosa through Hostias.

- 17 September 1803: Süssmayr dies of tuberculosis. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the St. Marx Cemetery.

- 15 June 1809: Requiem was performed at a memorial service for Joseph Haydn.

- 1825: Gottfried Weber writes an article in the music journal Cäcilia calling Mozart’s Requiem a spurious work.

- 24 March 1826: Constanze’s second husband Georg Nikolaus von Nissen dies. Her younger son Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart conducts Mozart’s Requiem at the service.

- 5 December 1826: On the 35th Anniversary of his father’s death, Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart conducts Mozart’s Requiem at St. George’s Ukrainian Greek Catholic Cathedral in Lviv (Lemberg).[12]

- 11 November 1827: Count Walsegg dies. Karl Haag, a musician formerly in Walsegg’s service, receives his score (Mozart’s autograph of the Introitus and Kyrie; the rest a copy by Süssmayr) and when he dies, he wills it to Katharina Adelpoller.

- 1831: Abbé Stadler gives the leaves of the Requiem autograph in his possession to the Imperial Court Library.

- 1833: Eybler suffered a stroke while conducting a performance of Mozart’s Requiem. The leaves of the Requiem autograph in his possession are turned over to the Imperial Court Library.

- 8 November 1833: Abbé Stadler dies.

- 1838: Count Moritz von Dietrichstein asks Nowack, formerly an employee of Walsegg, to search among Haag’s possessions for six Mozart string quartets that may have been given to Walsegg. Nowack does not find them, but discovers Walsegg’s score of Mozart’s Requiem. The Imperial Court Library pays Adelpoller 50 ducats for the score.

- 21 September 1839: Gottfried Weber dies.

- 15 December 1840: François Habeneck conducts the Paris Opera in a performance of the Requiem at the reburial of Napoleon I.

- 6 March 1842: Constanze Mozart dies.

- 29 July 1844: Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart dies.

- 24 July 1846: Eybler dies.

- 30 October 1849: Requiem was performed at Frédéric Chopin‘s funeral.

- 19 January 1964: Requiem was performed as a memorial mass for President John F. Kennedy by Cardinal Richard Cushing, Archbishop of Boston, at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston, MA.[13]

- 5 December 1991: Sir Georg Solti conducted the Requiem with the Vienna Philharmonic at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna at a memorial mass by Cardinal Hans Hermann Groër for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on the bicentenary of his death.

- 19 July 1994: Zubin Mehta conducted Sarajevo Philharmonic Orchestra in the ruins of The Great Counsel Hall in Sarajevo giving an extraordinary concert with soloists Cecilia Gasdia, Ildikó Komlósi, José Carreras and Ruggero Raimondi, It was filmed and transmitted by TV to popularise a charity aid for victims of Siege of Sarajevo.

- 1999: Claudio Abbado conducted the Requiem with the Berlin Philharmonic at the Salzburg Cathedral at a memorial concert on the 10th anniversary of the death of Herbert von Karajan.

- 2001: In Poznań, Poland, a special Tridentine Mass was celebrated during the night of 210th anniversary of Mozart’s death, with full usage of the Requiem. This mass has been repeated every year on 4 December.

Use of the Requiem in other funerals and memorial services

19th-century musicians whose funerals or memorial services used Mozart’s Requiem included Carl Fasch (1800); Giovanni Punto (1803); Joseph Haydn (1809); Jan Ladislav Dussek (1812); Giovanni Paisiello (1816); Andreas Romberg (1821); Johann Gottfried Schicht (1823); Carl Maria von Weber (1826); Ludwig van Beethoven (1827); Franz Schubert (1828); Alexandre-Étienne Choron (1834); Mme Blasis (1838); Ludwig Berger (1839); Frédéric Chopin (1849); Luigi Lablache (1858); Gioachino Rossini (1868); Hector Berlioz (1869); and Charles Hallé (1895).

19th-century artists whose funerals or memorial services used Mozart’s Requiem included Friedrich Schiller (1805); Heinrich Joseph von Collin (1811); Johann Franz Hieronymous Brockmann (1812); Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1832); and Peter von Cornelius (1867).

Among other 19th-century figures whose funerals or memorial services used Mozart’s Requiem included Carl Wilhelm Müller [de] (1801); Jean Lannes, 1st Duc de Montebello (1810); Princess Charlotte of Wales (1817); Maria Isabel of Portugal (1819); August Hermann Niemeyer (1828); Thomas Weld (1837); Napoleon (1840); John England (1842); John Fane, 11th Earl of Westmorland (1860); and Nicholas Wiseman (1865).

Influences

Mozart esteemed Handel and in 1789 he was commissioned by Baron Gottfried van Swieten to rearrange Messiah. This work likely influenced the composition of Mozart’s Requiem; the Kyrie is based on the And with his stripes we are healed chorus from Handel’s Messiah (HWV 56), since the subject of the fugato is the same with only slight variations by adding ornaments on melismata.[14] However, the same four note theme is also found in the finale of Haydn’s String Quartet in F minor (Op. 20 No. 5) and in the first measure of the A minor fugue from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier Book no. 2 (BWV 889b) as part of the subject of Bach’s fugue[15], and it is thought that Mozart transcribed some of the fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier for string ensemble (K. 404a Nos. 1-3 and K. 405 Nos. 1-5)[16], but the attribution of these transcriptions to Mozart is not certain[17].

Some believe that the Introitus was inspired by Handel’s Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline (HWV 264), and some have also remarked that the Confutatis may have been inspired by Sinfonia Venezia by Pasquale Anfossi. Another influence was Michael Haydn‘s Requiem in C minor which he and his father heard at the first three performances in January 1772. Some have noted that M. Haydn’s «Introitus» sounds rather similar to Mozart’s, and the theme for Mozart’s ‘Quam olim Abrahae’ fugue is a direct quote of the theme from Haydn’s Offertorium and Versus. In Introitus bar 21 the soprano sings “Te decet hymnus Deus in Zion”. It is quoting the Lutheran hymn “Meine seele erhebet den Herren”. The melody is used by many composers e.g. in Bach’s Cantata Meine Seel erhebt den Herren BWV 10 but also in M. Haydn’s Requiem.[18]

Myths surrounding the Requiem

With multiple levels of deception surrounding the Requiem’s completion, a natural outcome is the mythologizing which subsequently occurred. One series of myths surrounding the Requiem involves the role Antonio Salieri played in the commissioning and completion of the Requiem (and in Mozart’s death generally). While the most recent retelling of this myth is Peter Shaffer‘s play Amadeus and the movie made from it, it is important to note that the source of misinformation was actually a 19th-century play by Alexander Pushkin, Mozart and Salieri, which was turned into an opera by Rimsky-Korsakov and subsequently used as the framework for Amadeus.[19]

The autograph at the 1958 World’s Fair

File:Mozart K626 Arbeitspartitur last page.jpg Mozart’s manuscript with missing corner

The autograph of the Requiem was placed on display at the World’s Fair in 1958 in Brussels. At some point during the fair, someone was able to gain access to the manuscript, tearing off the bottom right-hand corner of the second to last page (folio 99r/45r), containing the words «Quam olim d: C:» (an instruction that the «Quam olim» fugue of the Domine Jesu was to be repeated da capo, at the end of the Hostias). The perpetrator has not been identified and the fragment has not been recovered.[20]

If the most common authorship theory is true, then «Quam olim d: C:» might very well be the last words Mozart wrote before he died. It is probable that whoever stole the fragment believed that to be the case.

Selected recordings

In the following table, large choirs and orchestras are marked by red background, ensembles playing on «period instruments» in «historically informed performance» are marked by a green background under the header Instr..

Template:Cantata discography header

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

Template:Cantata discography row

|}

Other recordings

- Ralf Otto [de], Bachchor Mainz [de] (Levin completion), L’arpa festante München, Julia Kleiter [de], Gerhild Romberger, Daniel Sans, Klaus Mertens, NCA

- Christoph Spering, Chorus Musicus, Das Neue Orchester, Iride Martinez, Monica Groop, Steve Davislim, Kwangchul Youn, Opus 111 (2002)

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Arnold Schoenberg Chor, Concentus Musicus Wien, Christine Schäfer, Bernarda Fink, Kurt Streit, Gerald Finley, Deutsche Harmonia Mundi

- Carl Czerny transcription for soli, coro and piano four hands: Antonio Greco, Coro Costanzo Porta, Diego Maccagnola, Anna Bessi, Silvia Frigato, Raffaele Giordani, Riccardo Demini. Discantica (2012)

- John Butt conducting the Dunedin Consort on the Linn Records label. The first recording to use David Black’s new critical edition of the Süssmayr version, it attempts to reconstruct the performing forces at the first performances in Vienna in 1791 and 1793. It won the 2014 Gramophone Award for Best Choral Recording.[21]

- Zdeněk Košler conducting the Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus, with Magdaléna Hajóssyová, Jaroslava Horská, Jozef Kundlák and Peter Mikuláš, Naxos, 1989: recorded at the Reduta, Bratislava, March 1985.

Scores of Mozart’s Requiem

- Template:NMA

- Template:NMA

- Template:ChoralWiki

- Template:IMSLP

References

- ↑ Blom, Jan Dirk (2009). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer. p. 342.

- ↑ Gehring, Franz Eduard (1883). Mozart (The Great Musicians). University of Michigan: S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. p. 124.

- ↑ Wolff, Christoph (1994). Mozart’s Requiem. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 3.

- ↑ Leeson (2004) Daniel N. Opus Ultimum: The Story of the Mozart Requiem, Algora Publishing, New York, p. 79: «Mozart might have described specific instrumentation for the drafted sections, or the addition of a Sanctus, a Benedictus, and an Agnus Dei, telling Süssmayr he would be obliged to compose those sections himself.»

- ↑ R. J. Summer, Choral Masterworks from Bach to Britten: Reflections of a Conductor Rowman & Littlefield p. 28

- ↑ Mentioned in the CD booklet of the Requiem recording by Nikolaus Harnoncourt (2004).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Landon, H. C. Robbins (1988). 1791: Mozart’s Last Year. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Steve Boerner (December 16, 2000). «K. 626: Requiem in D Minor». The Mozart Project.

- ↑ Paul Moseley: «Mozart’s Requiem: A Revaluation of the Evidence» J Royal Music Assn (1989; 114) pp. 203–237

- ↑ Wolff, Christoph. Mozart’s Requiem: historical and analytical studies, documents, score, 1998, University of California Press, p. 65

- ↑ Wolff, Christoph (1998). The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ «What Musical Events did Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart Organize?». Myron Yusypovych. 2016.

- ↑ Fenton, John H. (January 20, 1964). «Boston Symphony Plays for Requiem Honoring Kennedy». The New York Times. p. 1.

- ↑ «Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s ‘Kyrie Eleison, K. 626’ — Discover the Sample Source». WhoSampled. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ Dirst, Charles Matthew (2012). Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 1107376289.

- ↑ Köchel, Ludwig Ritter von (1862). Chronologisch-thematisches Verzeichniss sämmtlicher Tonwerke Wolfgang Amade Mozart’s (in German). Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. OCLC 3309798. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008.

, No. 405, pp. 328–329 - ↑ «Preludes and Fugues, K.404a (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus) — IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library: Free Public Domain Sheet Music». imslp.org. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- ↑ «Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s ‘Requiem in D Minor’ — Discover the Sample Source». WhoSampled. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ↑ Gregory Allen Robbins. «Mozart & Salieri, Cain & Abel: A Cinematic Transformation of Genesis 4.», Journal of Religion and Film: Vol. 1, No. 1, April 1997

- ↑ Facsimile of the manuscript’s last page, showing the missing corner

- ↑ «Mozart: Requiem, K626 (including reconstruction of first performance, December 10, 1791)». Gramophone. 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

Bibliography

- C. R. F. Maunder (1988). Mozart’s Requiem: On Preparing a New Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316413-2.

- Christoph Wolff (1994). Mozart’s Requiem: Historical and Analytical Studies, Documents, Score. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07709-1.

- Brendan Cormican (1991). Mozart’s death – Mozart’s requiem: an investigation. Belfast, Northern Ireland: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-9510357-0-3.

- Heinz Gärtner (1991). Constanze Mozart: after the Requiem. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-39-X.

- Simon P. Keefe (2012). Mozart’s Requiem: Reception, Work, Completion. Canmbridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19837-0.

- Requiem (2005) Decca Music Group Limited. Barcode 00028947570578

External links

- Article on the Requiem at h2g2

- Michael Lorenz: «Freystädtler’s Supposed Copying in the Autograph of K. 626: A Case of Mistaken Identity», Vienna 2013

- Mozart’s Requiem, new completion of the score by musicologist Robert D. Levin, live concert

Template:Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Template:Mozart masses

Template:Infobox musical composition

The Requiem in D minor, K. 626, is a requiem mass by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart composed part of the Requiem in Vienna in late 1791, but it was unfinished at his death on 5 December the same year. A completed version dated 1792 by Franz Xaver Süssmayr was delivered to Count Franz von Walsegg, who commissioned the piece for a Requiem service to commemorate the anniversary of his wife’s death on 14 February.

The autograph manuscript shows the finished and orchestrated Introit in Mozart’s hand, and detailed drafts of the Kyrie and the sequence Dies Irae as far as the first eight bars of the «Lacrymosa» movement, and the Offertory. It cannot be shown to what extent Süssmayr may have depended on now lost «scraps of paper» for the remainder; he later claimed the Sanctus and Agnus Dei as his own. Walsegg probably intended to pass the Requiem off as his own composition, as he is known to have done with other works. This plan was frustrated by a public benefit performance for Mozart’s widow Constanze. She was responsible for a number of stories surrounding the composition of the work, including the claims that Mozart received the commission from a mysterious messenger who did not reveal the commissioner’s identity, and that Mozart came to believe that he was writing the requiem for his own funeral.

The Requiem is scored for 2 basset horns in F, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets in D, 3 trombones (alto, tenor & bass), timpani (2 drums), violins, viola and basso continuo (cello, double bass, and organ). The vocal forces include soprano, contralto, tenor, and bass soloists and an SATB mixed choir.

Structure

Süssmayr’s completion divides the Requiem into fourteen movements:

File:Manuscript of the last page of Requiem.jpg Bars 1–5 of the Lacrymosa

- I. Introitus

- Requiem (choir and soprano solo) (D minor)

- II. Kyrie (choir) (D minor)

- III. Sequentia (text based on sections of the Dies Irae)

- Dies irae (choir) (D minor)

- Tuba mirum (soprano, contralto, tenor and bass solo) (B-flat major)

- Rex tremendae (choir) (G minor–D minor)

- Recordare (soprano, contralto, tenor and bass solo) (F major)

- Confutatis (choir) (A minor–F major, last chord V of D minor)

- Lacrymosa (choir) (D minor)

- IV. Offertorium

- Domine Jesu (choir with solo quartet) (G minor)

- Hostias (choir) (E-flat major–G minor)

- V. Sanctus (choir) (D major)

- VI. Benedictus (solo quartet and choir) (B-flat major)

- VII. Agnus Dei (choir) (D minor–B-flat major)

- VIII. Communio

- Lux aeterna (soprano solo and choir) (B-flat major–D minor)

All sections from the Sanctus onwards are not present in Mozart’s manuscript fragment. Mozart may have intended to include the Amen fugue at the end of the Sequentia, but Süssmayr did not do so in his completion.

The Introitus is in D minor and finishes on a half-cadence that transitions directly into Kyrie. The Kyrie is a double fugue, with one subject setting the words «Kyrie eleison» and the other «Christe eleison«. The movement Tuba mirum opens with a trombone solo accompanying the bass. The Confutatis is well known for its string accompaniment; it opens with agitated figures that accentuate the wrathful sound of the basses and tenors, but it turns into soft arpeggios in the second phrase while accompanying the soft sounds of the sopranos and altos.

Details

The following table shows for the eight movements in Süssmayr’s completion with their subdivisions the title and incipit, the type of movement, the vocal parts soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T) and bass (B) and four-part choir SATB, the tempo, key and time.

Template:Classical movement header

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

Template:Classical movement row

|}

History

Composition

At the time of Mozart’s death on 5 December 1791, only the first two movements «Requiem aeternam» and «Kyrie» were completed in all of the orchestral and vocal parts. The «Sequence» and the «Offertorium» were completed in skeleton, with the exception of the «Lacrymosa», which breaks off after the first eight bars. The vocal parts and the continuo were fully notated. Occasionally, some of the prominent orchestral parts were briefly indicated, such as the first violin part of the Rex tremendae and Confutatis, the musical bridges in the Recordare, and the trombone solos of the «Tuba Mirum». What remained to be completed for these sections were mostly accompanimental figures, inner harmonies, and orchestral doublings to the vocal parts.

Constanze Mozart and the Requiem after Mozart’s death

The eccentric count Franz von Walsegg commissioned the Requiem from Mozart anonymously through intermediaries. The count, an amateur chamber musician who routinely commissioned works by composers and passed them off as his own,[1][2] wanted a Requiem Mass he could claim he composed to memorialize the recent passing of his wife. Mozart received only half of the payment in advance, so upon his death his widow Constanze was keen to have the work completed secretly by someone else, submit it to the count as having been completed by Mozart and collect the final payment.[3] Joseph von Eybler was one of the first composers to be asked to complete the score, and had worked on the movements from the Dies irae up until the Lacrymosa. In addition, a striking similarity between the openings of the Domine Jesu Christe movements in the requiems of the two composers suggests that Eybler at least looked at later sections.Template:Explain After this work, he felt unable to complete the remainder, and gave the manuscript back to Constanze Mozart.

The task was then given to another composer, Franz Xaver Süssmayr. Süssmayr borrowed some of Eybler’s work in making his completion, and added his own orchestration to the movements from the Kyrie onward, completed the Lacrymosa, and added several new movements which a Requiem would normally comprise: Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei. He then added a final section, Lux aeterna by adapting the opening two movements which Mozart had written to the different words which finish the Requiem mass, which according to both Süssmayr and Mozart’s wife was done according to Mozart’s directions. Some people consider it unlikely, however, that Mozart would have repeated the opening two sections if he had survived to finish the work.

Other composers may have helped Süssmayr. The Agnus Dei is suspected by some scholars[4] to have been based on instruction or sketches from Mozart because of its similarity to a section from the Gloria of a previous mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220) by Mozart,[5] as was first pointed out by Richard Maunder. Others have pointed out that in the beginning of the Agnus Dei the choral bass quotes the main theme from the Introitus.[6] Many of the arguments dealing with this matter, though, center on the perception that if part of the work is high quality, it must have been written by Mozart (or from sketches), and if part of the work contains errors and faults, it must have been all Süssmayr’s doing.[citation needed]

Another controversy is the suggestion (originating from a letter written by Constanze) that Mozart left explicit instructions for the completion of the Requiem on «little scraps of paper.» The extent to which Süssmayr’s work may have been influenced by these «scraps» if they existed at all remains a subject of speculation amongst musicologists to this day.

The completed score, initially by Mozart but largely finished by Süssmayr, was then dispatched to Count Walsegg complete with a counterfeited signature of Mozart and dated 1792. The various complete and incomplete manuscripts eventually turned up in the 19th century, but many of the figures involved left ambiguous statements on record as to how they were involved in the affair. Despite the controversy over how much of the music is actually Mozart’s, the commonly performed Süssmayr version has become widely accepted by the public. This acceptance is quite strong, even when alternative completions provide logical and compelling solutions for the work.

The confusion surrounding the circumstances of the Requiem’s composition was created in a large part by Mozart’s wife, Constanze[citation needed]. Constanze had a difficult task in front of her: she had to keep secret the fact that the Requiem was unfinished at Mozart’s death, so she could collect the final payment from the commission. For a period of time, she also needed to keep secret the fact that Süssmayr had anything to do with the composition of the Requiem at all, in order to allow Count Walsegg the impression that Mozart wrote the work entirely himself. Once she received the commission, she needed to carefully promote the work as Mozart’s so that she could continue to receive revenue from the work’s publication and performance. During this phase of the Requiem’s history, it was still important that the public accept that Mozart wrote the whole piece, as it would fetch larger sums from publishers and the public if it were completely by Mozart.

It is Constanze’s efforts that created the flurry of half-truths and myths almost instantly after Mozart’s death. According to Constanze, Mozart declared that he was composing the Requiem for himself, and that he had been poisoned. His symptoms worsened, and he began to complain about the painful swelling of his body and high fever. Nevertheless, Mozart continued his work on the Requiem, and even on the last day of his life, he was explaining to his assistant how he intended to finish the Requiem. Source materials written soon after Mozart’s death contain serious discrepancies, which leave a level of subjectivity when assembling the «facts» about Mozart’s composition of the Requiem. For example, at least three of the conflicting sources, both dated within two decades following Mozart’s death, cite Constanze as their primary source of interview information. In 1798, Friedrich Rochlitz, a German biographical author and amateur composer, published a set of Mozart anecdotes that he claimed to have collected during his meeting with Constanze in 1796.[7]

The Rochlitz publication makes the following statements:

- Mozart was unaware of his commissioner’s identity at the time he accepted the project.

- He was not bound to any date of completion of the work.

- He stated that it would take him around four weeks to complete.

- He requested, and received, 100 ducats at the time of the first commissioning message.

- He began the project immediately after receiving the commission.

- His health was poor from the outset; he fainted multiple times while working.

- He took a break from writing the work to visit the Prater with his wife.

- He shared the thought with his wife that he was writing this piece for his own funeral.

- He spoke of «very strange thoughts» regarding the unpredicted appearance and commission of this unknown man.

- He noted that the departure of Leopold II to Prague for the coronation was approaching.

The most highly disputed of these claims is the last one, the chronology of this setting. According to Rochlitz, the messenger arrives quite some time before the departure of Leopold for the coronation, yet there is a record of his departure occurring in mid-July 1791. However, as Constanze was in Baden during all of June to mid-July, she would not have been present for the commission or the drive they were said to have taken together.[7] Furthermore, The Magic Flute (except for the Overture and March of the Priests) was completed by mid-July. La clemenza di Tito was commissioned by mid-July.[7] There was no time for Mozart to work on the Requiem on the large scale indicated by the Rochlitz publication in the time frame provided.

Also in 1798, Constanze is noted to have given another interview to Franz Xaver Niemetschek,[8] another biographer looking to publish a compendium of Mozart’s life. He published his biography in 1808, containing a number of claims about Mozart’s receipt of the Requiem commission:

- Mozart received the commission very shortly before the Coronation of Emperor Leopold II, and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee, but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

- He fell ill while writing the work

- He told Constanze «I am only too conscious…my end will not be long in coming: for sure, someone has poisoned me! I cannot rid my mind of this thought.»

- Constanze thought that the Requiem was overstraining him; she called the doctor and took away the score.

- On the day of his death he had the score brought to his bed.

- The messenger took the unfinished Requiem soon after Mozart’s death.

- Constanze never learned the commissioner’s name.

This account, too, has fallen under scrutiny and criticism of its accuracy. According to letters, Constanze most certainly knew the name of the commissioner by the time this interview was released in 1800.[8] Additionally, the Requiem was not given to the messenger until some time after Mozart’s death.[7] This interview contains the only account from Constanze herself of the claim that she took the Requiem away from Wolfgang for a significant duration during his composition of it.[7] Otherwise, the timeline provided in this account is historically probable. However, the most highly accepted text attributed to Constanze is the interview to her second husband, Georg Nikolaus von Nissen.[7] After Nissen’s death in 1826, Constanze released the biography of Wolfgang (1828) that Nissen had compiled, which included this interview. Nissen states:

- Mozart received the commission shortly before the coronation of Emperor Leopold and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee, but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

The Nissen publication lacks information following Mozart’s return from Prague.[7]

Modern completions

Template:Refimprove section

In the 1960s a sketch for an Amen fugue was discovered, which some musicologists (Levin, Maunder) believe belongs to the Requiem at the conclusion of the sequence after the Lacrymosa. H. C. Robbins Landon argues that this Amen fugue was not intended for the Requiem, rather that it «may have been for a separate unfinished mass in D minor» to which the Kyrie K. 341 also belonged. There is, however, compelling evidence placing the «Amen Fugue» in the Requiem[9] based on current Mozart scholarship. First, the principal subject is the main theme of the requiem (stated at the beginning, and throughout the work) in strict inversion. Second, it is found on the same page as a sketch for the Rex tremendae (together with a sketch for the overture of his last opera The Magic Flute), and thus surely dates from late 1791. The only place where the word ‘Amen’ occurs in anything that Mozart wrote in late 1791 is in the sequence of the Requiem. Third, as Levin points out in the foreword to his completion of the Requiem, the addition of the Amen Fugue at the end of the sequence results in an overall design that ends each large section with a fugue.

Since the 1970s several composers and musicologists, dissatisfied with the traditional «Süssmayr» completion, have attempted alternative completions of the Requiem. Each version follows a distinct methodology for completion:

- Franz Beyer – makes revisions to Süssmayr‘s orchestration in an attempt to create a more Mozartian style and makes a few minor changes to Süssmayr’s sections (i.e. lengthening the Osanna fugue slightly for a more conclusive sounding ending).

- H. C. Robbins Landon – orchestrates parts of the completion using the partial work by Eybler, thinking that Eybler’s work is a more reliable guide of Mozart’s intentions.

- Richard Maunder – dispenses completely with the parts known to be written by Süssmayr, but retains the Agnus Dei after discovering an extensive paraphrase from an earlier mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220). Recomposes the Lacrymosa from bar 9 onwards, and includes a completion of the Amen fugue.

- Duncan Druce – makes slight changes in orchestration, but retains Eybler’s ninth and tenth measures of the Lacrymosa, lengthening the movement substantially to end in the «Amen Fugue». He also completely rewrites the Benedictus, only retaining the opening theme.

- Robert D. Levin and Simon Andrews – each retain the structure of Süssmayr while adjusting orchestration, voice leading and in some cases rewriting entire sections in an effort to make the work more Mozartean.

- Pánczél Tamás – makes revisions to Süssmayr’s score in a manner similar to Beyer, but extends the Lacrymosa significantly past Süssmayr’s passages and rewrites the Benedictus’s ending leading into the Osanna reprise.

- Clemens Kemme – orchestration rewritten in a style closer to Eybler’s, emphasing the basset horns in particular, with a reworked Sanctus, Benedictus and extended Osanna fugue.

- Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs – provides an entirely new instrumentation, based on Eybler’s ideas, new elaborations of the Amen and Osanna fugues, and a new continuity of the Lacrymosa (after b. 18), Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei, following those bars of which Dr. Cohrs assumes Mozart might have sketched himself.

- Masaaki Suzuki – follows a methodology similar to Robbins Landon, but with further stylistic elaboration on Süssmayr’s sections.

- Marius Flothuis – revision of Süssmayr’s version via removal of vocal doubling, rewriting of the trombone parts and the harmonic transition to the Osanna reprise in the Benedictus.

- Timothy Jones – reworking of the Lacrymosa, composition of an extensive Amen fugue modeled on the ‘Cum sancto spiritu’ fugue from the Great Mass in C minor, K. 427, and a long elaboration on Süssmayr’s Osanna fugue.

- Michael Finnissy – takes the Süssmayr completion as its basis and adheres to Mozart’s scoring. Of the five movements newly completed by Finnissy the ‘Lacrymosa’ has been written in Mozartian style while the four final movements represent an exploration of musical styles since Mozart’s death in 1791.

- Knud Vad – follows Süssmayr’s completion until the Sanctus and Benedictus which are noticeably rewritten in places (i.e. Osanna turned into a double fugue played adagio)

- Gregory Spears – includes a new “Sanctus,” “Benedictus” and “Agnus Dei” designed to replace the Süssmayr completion of those movements. Spears’s completion recognizes the juxtaposition of old and new sources common in liturgical music of the period, and incorporates two cadential fragments from Süssmayr’s completion into the end of his “Benedictus” and “Agnus Dei”.

- Letho Kostoglou (Australian musicologist) – utilises primarily music composed by Mozart. It was performed at Adelaide Town Hall on 4 September 2010. This edition was endorsed by Richard Bonynge and Patrick Thomas.

- Pierre-Henri Dutron‘s edits are largely a revision of Süssmayr’s version. Sanctus and Benedictus significantly rewritten from opening themes onward. Creative liberties are taken with regard to the dispersion of the vocal material between the chorus and soloists. This version was used by conductor René Jacobs for his performances given at the end of 2016.

In the Levin, Andrews, Druce and Cohrs versions, the Sanctus fugue is completely rewritten and re-proportioned and the Benedictus is restructured to allow for a reprise of the Sanctus fugue in the key of D (rather than Süssmayr’s use of B-flat).

Maunder, Levin, Druce, Suzuki, Tamás, Cohrs and Jones use the sketch for the Amen fugue discovered in the 1960s to compose a longer and more substantial setting to the words «Amen» at the end of the sequence. In the Süssmayr version, «Amen» is set as a plagal cadence with a Picardy third (iv–I in D minor) at the end of the Lacrymosa: the Andrews version uses the Süssmayr ending. Jones combines the two, ending his Amen fugue with a variation on the concluding bars of Süssmayr’s Lacrymosa as well as the aforementioned plagal cadence.

Supplementary works by other composers

For a performance of the Requiem in Rio de Janeiro in December 1819, Austrian composer Sigismund von Neukomm constructed a further movement based on material in the Süssmayr version. Incorporating music from various movements including the Requiem aeternum, Dies irae, Lacrymosa and Agnus Dei, the bulk of the piece is set to the Libera me, a responsory text which is traditionally sung after the Requiem mass, and concludes with a reprise of the Kyrie and a final Requiescat in pace. A contemporary of Neukomm and a pupil of Mozart’s, Ignaz von Seyfried would compose his own Mozart-inspired Libera me for a performance at Ludwig van Beethoven‘s funeral in 1827.

Timeline

Template:Refimprove section

Before 1791

- 2 January 1772: Mozart participates in the premiere of Michael Haydn‘s Requiem in C minor.[10]

- 21 September 1784: Birth of Mozart’s older son, Karl Thomas Mozart.

- 20 April 1789: Mozart visits Leipzig where he studied works by Bach.[11]

- December 1790: Mozart completes his string quintet in D (K. 593) and the Adagio and Allegro in F minor for a mechanical organ (K. 594). These are his first works in a new burst of creativity after a very low production of works in 1790.

1791

- 5 January: Mozart completes his last piano concerto, in B-flat (K. 595).

- 14 January: Mozart completes three German songs (K. 596–8).

- January–March: Mozart composes mostly dance music (K. 599–611).

- 14 February: Anna, Count von Walsegg’s wife, dies at the age of 20.

- 3 March: Mozart completes the Fantasia in F minor for a mechanical organ (K. 608).

- 8 March: Mozart completes the bass aria Per questa bella mano (K. 612).

- March: Mozart completes the Variations in F on «Ein Weib ist das herrlichste Ding» (K. 613).

- 12 April: Mozart completes his last string quintet, in E-flat (K. 614).

- May 4: Mozart completes the Andante in F for a small mechanical organ (K. 616).

- 23 May: Mozart completes the Adagio and Rondo for glass harmonica, flute, oboe, viola and cello, his last chamber work (K. 617).

- 17 June: Mozart completes the motet Ave verum corpus (K. 618).

- July: Mozart completes the cantata Die ihr des unermeßlichen Weltalls (K. 619).

- mid-July: A messenger (probably Franz Anton Leitgeb, the count’s steward) arrives with note asking Mozart to write a Requiem mass.

- mid-July: Commission from Domenico Guardasoni, impresario of the Prague National Theatre to compose the opera, La clemenza di Tito (K. 621), for the festivities surrounding the coronation on September 6 of Leopold II as King of Bohemia.

- 26 July: Birth of Mozart’s younger son, Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart.

- August: Mozart works mainly on La clemenza di Tito; completed by September 5.

- 25 August: Mozart leaves for Prague.

- 6 September: Mozart conducts premiere of La clemenza di Tito.

- mid-September – 28 September: Revision and completion of The Magic Flute (K. 620).

- 30 September: Premiere of The Magic Flute.

- 7 October: Mozart completes Clarinet Concerto in A major (K. 622).

- 8 October – 20 November: Mozart works on the Requiem and a cantata (K. 623).

- 15 November: Mozart completes the cantata.

- 20 November: Mozart is confined to bed due to his illness.

- 5 December: Mozart dies shortly after midnight.

- 7 December: Burial in St. Marx Cemetery.

- 5 December through 10 December: Kyrie from Requiem completed by unknown composer (once identified as Mozart’s pupil Franz Jakob Freystädtler, although this attribution is not generally accepted now)

- 10 December: Requiem (probably only Introitus and Kyrie) were performed in St. Michael’s Church, Vienna, for a memorial for Mozart by the staff of the Theater auf der Wieden.

- 21 December: Joseph Leopold Eybler receives score of Requiem from Constanze, promising to complete it by mid-Lent (mid-March) of next year. He later gives up and returns the score to Constanze, who turns it to Süssmayr to complete.

After 1791

- Early March 1792: probably the time Süssmayr finished the Requiem

- 2 January 1793: Performance of Requiem for Constanze’s benefit arranged by Gottfried van Swieten

- Early December 1793: Requiem delivered to the Count

- 14 December 1793: Requiem performed in memory of the count’s wife in the church at Wiener-Neustadt[citation needed]

- 14 February 1794: Requiem performed again in Patronat Church Maria Schutz [de] in Semmering

- 1799: Breitkopf & Härtel published the Requiem.

- 1800 or later: Walsegg receives leaves 1 through 10 of the autograph (Introitus and Kyrie)

- Autumn 1800: Abbé Maximilian Stadler compares all known manuscript copies (including Walsegg’s) and editions of the score, and noted down copying errors and determined precisely which parts of the Requiem were written by Mozart.

- After 1802: Abbé Stadler receives leaves 11 through 32 (Dies irae to Confutatis) of Mozart’s Requiem autograph from Constanze. Later Eybler would receive leaves 33 to 46, the Lacrymosa through Hostias.

- 17 September 1803: Süssmayr dies of tuberculosis. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the St. Marx Cemetery.

- 15 June 1809: Requiem was performed at a memorial service for Joseph Haydn.

- 1825: Gottfried Weber writes an article in the music journal Cäcilia calling Mozart’s Requiem a spurious work.

- 24 March 1826: Constanze’s second husband Georg Nikolaus von Nissen dies. Her younger son Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart conducts Mozart’s Requiem at the service.

- 5 December 1826: On the 35th Anniversary of his father’s death, Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart conducts Mozart’s Requiem at St. George’s Ukrainian Greek Catholic Cathedral in Lviv (Lemberg).[12]

- 11 November 1827: Count Walsegg dies. Karl Haag, a musician formerly in Walsegg’s service, receives his score (Mozart’s autograph of the Introitus and Kyrie; the rest a copy by Süssmayr) and when he dies, he wills it to Katharina Adelpoller.

- 1831: Abbé Stadler gives the leaves of the Requiem autograph in his possession to the Imperial Court Library.

- 1833: Eybler suffered a stroke while conducting a performance of Mozart’s Requiem. The leaves of the Requiem autograph in his possession are turned over to the Imperial Court Library.

- 8 November 1833: Abbé Stadler dies.

- 1838: Count Moritz von Dietrichstein asks Nowack, formerly an employee of Walsegg, to search among Haag’s possessions for six Mozart string quartets that may have been given to Walsegg. Nowack does not find them, but discovers Walsegg’s score of Mozart’s Requiem. The Imperial Court Library pays Adelpoller 50 ducats for the score.

- 21 September 1839: Gottfried Weber dies.

- 15 December 1840: François Habeneck conducts the Paris Opera in a performance of the Requiem at the reburial of Napoleon I.

- 6 March 1842: Constanze Mozart dies.

- 29 July 1844: Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart dies.

- 24 July 1846: Eybler dies.

- 30 October 1849: Requiem was performed at Frédéric Chopin‘s funeral.

- 19 January 1964: Requiem was performed as a memorial mass for President John F. Kennedy by Cardinal Richard Cushing, Archbishop of Boston, at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston, MA.[13]

- 5 December 1991: Sir Georg Solti conducted the Requiem with the Vienna Philharmonic at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna at a memorial mass by Cardinal Hans Hermann Groër for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on the bicentenary of his death.

- 19 July 1994: Zubin Mehta conducted Sarajevo Philharmonic Orchestra in the ruins of The Great Counsel Hall in Sarajevo giving an extraordinary concert with soloists Cecilia Gasdia, Ildikó Komlósi, José Carreras and Ruggero Raimondi, It was filmed and transmitted by TV to popularise a charity aid for victims of Siege of Sarajevo.

- 1999: Claudio Abbado conducted the Requiem with the Berlin Philharmonic at the Salzburg Cathedral at a memorial concert on the 10th anniversary of the death of Herbert von Karajan.

- 2001: In Poznań, Poland, a special Tridentine Mass was celebrated during the night of 210th anniversary of Mozart’s death, with full usage of the Requiem. This mass has been repeated every year on 4 December.

Use of the Requiem in other funerals and memorial services

19th-century musicians whose funerals or memorial services used Mozart’s Requiem included Carl Fasch (1800); Giovanni Punto (1803); Joseph Haydn (1809); Jan Ladislav Dussek (1812); Giovanni Paisiello (1816); Andreas Romberg (1821); Johann Gottfried Schicht (1823); Carl Maria von Weber (1826); Ludwig van Beethoven (1827); Franz Schubert (1828); Alexandre-Étienne Choron (1834); Mme Blasis (1838); Ludwig Berger (1839); Frédéric Chopin (1849); Luigi Lablache (1858); Gioachino Rossini (1868); Hector Berlioz (1869); and Charles Hallé (1895).

19th-century artists whose funerals or memorial services used Mozart’s Requiem included Friedrich Schiller (1805); Heinrich Joseph von Collin (1811); Johann Franz Hieronymous Brockmann (1812); Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1832); and Peter von Cornelius (1867).

Among other 19th-century figures whose funerals or memorial services used Mozart’s Requiem included Carl Wilhelm Müller [de] (1801); Jean Lannes, 1st Duc de Montebello (1810); Princess Charlotte of Wales (1817); Maria Isabel of Portugal (1819); August Hermann Niemeyer (1828); Thomas Weld (1837); Napoleon (1840); John England (1842); John Fane, 11th Earl of Westmorland (1860); and Nicholas Wiseman (1865).

Influences