Richard Buckminster Fuller, (born July 12, 1895, Milton, Massachusetts, U.S.—died July 1, 1983, Los Angeles, California), American engineer, architect, and futurist who developed the geodesic dome—the only large dome that can be set directly on the ground as a complete structure and the only practical kind of building that has no limiting dimensions (i.e., beyond which the structural strength must be insufficient). Among the most noteworthy geodesic domes is the United States pavilion for Expo 67 in Montreal. Also a poet and a philosopher, Fuller was noted for unorthodox ideas on global issues.

- Life

Fuller was descended from a long line of New England Nonconformists, the most famous of whom was his great-aunt, Margaret Fuller, the critic, teacher, woman of letters, and cofounder of The Dial, organ of the Transcendentalist movement. Fuller was twice expelled from Harvard University and never completed his formal education. He saw service in the U.S. Navy during World War I as commander of a crash-boat flotilla. In 1917 he married Anne Hewlett, daughter of James Monroe Hewlett, a well-known architect, and muralist. Hewlett had invented a modular construction system using a compressed fiber block, and after the war, Fuller and Hewlett formed a construction company that used this material (later known as Soundex, a Celotex product) in modules for house construction. In this operation, Fuller himself supervised the erection of several hundred houses.

The construction company encountered financial difficulties in 1927, and Fuller, a minority stockholder, was forced out. He found himself stranded in Chicago, without income, alienated, dismayed, confused. At this point in his life, Fuller resolved to devote his remaining years to a nonprofit search for design patterns that could maximize the social uses of the world’s energy resources and evolving industrial complex. The inventions, discoveries, and economic strategies that followed were interim factors related to that end.

In 1927, in the course of the development of his comprehensive strategy, he invented and demonstrated a factory-assembled, air-deliverable house, later called the Dymaxion house, which had its own utilities. He designed in 1928 and manufactured in 1933, the first prototype of his three-wheeled omnidirectional vehicle, the Dymaxion car. This automobile, the first streamlined car, could cross open fields like a jeep, accelerate to 120 miles (190 km) per hour, make a 180-degree turn in its own length, carry 12 passengers, and average 28 miles per gallon (12 km per liter) of gasoline. In 1943, at the request of the industrialist Henry Kaiser, Fuller developed a new version of the Dymaxion car that was planned to be powered by three separate air-cooled engines, each coupled to its own wheel by a variable fluid drive. The projected 1943 Dymaxion, like its predecessor, was never commercially produced.

Assuming that there is in nature a vectorial, or directionally oriented, the system of forces that provides maximum strength with minimum structures, as is the case in the nested tetrahedron lattices of organic compounds and of metals, Fuller developed a vectorial system of geometry that he called “Energetic-Synergetic geometry.” The basic unit of this system is the tetrahedron (a pyramid shape with four sides, including the base), which, in combination with octahedrons (eight-sided shapes), forms the most economic space-filling structures. The architectural consequence of the use of this geometry by Fuller was the geodesic dome, a frame the total strength of which increases in logarithmic ratio to its size. Many thousands of geodesic domes have been erected in various parts of the world, the most publicized of which was the United States exhibition dome at Expo 67 in Montreal. One houses the tropical exhibit area of the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, Another, the Union Tank Car Company’s dome, was built in 1958 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and, at the time of its construction, was the largest clear-span structure in existence, 384 feet (117 meters) in diameter and 116 feet (35 meters) in height.

Other inventions and developments by Fuller included a system of cartography that presents all the land areas of the world without significant distortion; die-stamped prefabricated bathrooms; tetrahedronal floating cities; underwater geodesic-domed farms; and expendable paper domes. Fuller did not regard himself as an inventor or an architect, however. All of his developments, in his view, were accidental or interim incidents in a strategy that aimed at a radical solution of world problems by finding the means to do more with less.

Comprehensive and anticipatory design initiative alone, he held—exclusive of politics and political theory—can solve the problems of human shelter, nutrition, transportation, and pollution; and it can solve these with a fraction of the materials now inefficiently used. Moreover, energy, ever more available, directed by cumulative information stored in computers, is capable of synthesizing raw materials, machining, and packaging commodities, and supplying the physical needs of the total global population.

Fuller was a research professor at Southern Illinois University (Carbondale) from 1959 to 1968. In 1968 he was named university professor, in 1972 distinguished university professor, and in 1975 university professor emeritus. Queen Elizabeth II awarded Fuller the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture. He also received the 1968 Gold Medal Award of the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

- Legacy

Fuller—architect, engineer, inventor, philosopher, author, cartographer, geometrician, futurist, teacher, and poet—established a reputation as one of the most original thinkers of the second half of the 20th century. He conceived of man as a passenger in a cosmic spaceship—a passenger whose only wealth consists of energy and information. Energy has two phases—associative (as atomic and molecule structures) and dissociative (as radiation)—and, according to the first law of thermodynamics, the energy of the universe cannot be decreased. Information, on the other hand, is negatively entropic; as for knowledge, technology, “know-how,” it constantly increases. Research engenders research, and each technological advance multiplies the productive wealth of the world community. Consequently, “Spaceship Earth” is a regenerative system whose energy is progressively turned to human advantage and whose wealth increases by geometric increments.

Fuller’s book Nine Chains to the Moon (1938) is an outline of his general technological strategy for maximizing the social applications of energy resources. He further developed this and other themes in such works as No More Secondhand God (1962), Utopia or Oblivion (1969), Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1969), Earth, Inc. (1973), and Critical Path (1981).

“When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty…….. but when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.” ― R. Buckminster Fuller

Source: Britannica

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

Buckminster Fuller

Biography

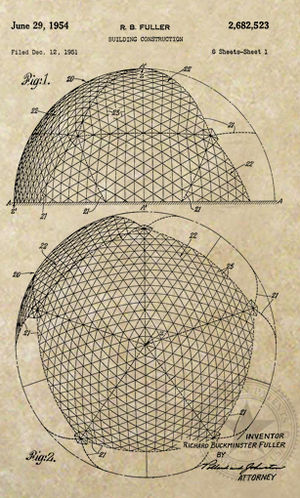

1954 patent issued to Richard Buckminster Fuller for his invention of the Geodesic Dome.

Born: 12 July 1895

Died: 01 July 1983

Buckminster Fuller was an American architect, utopian futurist, and inventor. He was concerned with the question of whether or not humanity would be able to survive as residents on the planet Earth for an extended amount of time, and if so how that would be done. The author of more than twenty-eight books and the creator of numerous inventions, he is best known for the invention of the geodesic dome and for his impact on the field of architecture. Fuller achieved only limited success in making his utopian ideas into reality, and most of his inventions were never put into production, but he did achieve a high degree of visibility later in his life and has influenced a wide spectrum of people. Through the power of his ideas and his unflagging optimism he became an inspirational figure for many people.

Fuller was born in 1895 in Milton, Massachusetts. A lackluster student, he briefly studied at Harvard before being expelled for his “irresponsibility and lack of interest.” He then went on to work in a variety of manual jobs, including a long stint as a meat packer. He served in the U.S. Navy during World War I, where he was employed as a radio operator, and in the 1920s he helped his father-in-law develop a business manufacturing light-weight building materials. The business went bankrupt, and left Fuller with very little money. In the winter of 1927, while living in low-quality housing in Chicago, his daughter died of pneumonia. The experience almost drove him to suicide, since he considered himself responsible, but at the last moment he decided instead to undertake “an experiment, to find what a single individual can contribute to changing the world and benefiting all humanity.”

From that point on, Fuller worked to develop inventions and ideas that might benefit humanity, most notably in the fields of architecture, transportation, and sustainable development. In 1932, for example, Fuller designed an aerodynamic car with three wheels — two in front and one in back — that was shaped like a tear-drop and could turn sharply. In the late 1920s he began experimenting with lightweight plastic building materials, constructing a small dome by assembling triangle components into geometric shapes. This “geodesic dome” became his most famous invention. Because the triangle is the basic unit of the structure, the dome is extremely stable and can be made out of very lightweight materials. Very large domes can be assembled that are structurally much stronger than similar sized buildings designed in other styles but made of similar materials. Recognizing the importance of the design, the military soon began building domes for radar stations and other buildings, and in the 1950s Fuller designed a number of very large and impressive domes, thereby establishing an international reputation for himself. The Epcot Center at Walt Disney World is probably the best-known example of a geodesic dome today, but there are numerous other examples scattered across the United States.

Fuller was profoundly optimistic about humanity’s chances for long-term survival. He was struck by how much things had changed in a relatively short amount of time—for example, by the fact that illnesses that used to kill even the most elite members of society are now routinely treated even among the relatively poor. He believed that sometime soon everyone alive would be able to live like a “billionaire” if resources were simply used more and more efficiently (an idea he called “ephemeralization”). Wealth can be increased, he argued, by recycling resources into newer products whose more technically sophisticated designs requires less material and occupy less space. Fuller argued that the world’s accumulation of relevant knowledge, combined with bulk quantities of key recyclable resources that had already been extracted from the earth, had reached a watershed level in which competition for resources is no longer necessary. As a result, he argued, cooperation has become the ideal survival strategy. “Selfishness”, as he put it, “is unnecessary and…unrationalizable.” With these types of arguments, Fuller tried to inspire humanity to understand that even in the context of limited resources an endlessly ever-increasing standard of living is possible for everyone. We are all passengers, he argued, on “spaceship earth.” Although most of his ideas never materialized, the strength of his vision continues to inspire.

Buckminster Fuller is not only known for being one of the brightest inventors of his time but also for having received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his “contributions as geometrician, educator and architect-designer” that were “benchmarks of accomplishment in their fields”. Richard Buckminster Fuller’s amazing ideas and inventions were often the results of approaching practical problems with both scientific knowledge and “outside the box thinking”. The following success story about Buckminster Fuller is separated into two parts; the first one consisting of the achievements in his life, the second one focusing on his personal life, which is also quite interesting.

Buckminster Fuller’s Career

The American engineer, inventor, architect and author Richard Buckminster Fuller, commonly known as “Bucky”, was born in 1895 in Milton, Massachusetts. Bucky Fuller spend a lot of his youth on Bear Island where he started to experiment with materials from the woods to create different tools and started to design devices for the propulsion of small boats. The experiences Fuller made during his youth helped him tremendously at the age of 22, where he served in the U.S. Navy as a shipboard radio operator and crash-boat commander, as he invented a facility for the downed aircraft recovery team that allowed them to pull downed airplanes out of the water.

After being discharged from military service Fuller was ambitious to improve the housing conditions and started to develop the Stockade Building System with his father-in-law, James Hewlett, that consisted out of compressed wood shavings for weatherproof and light-weight and housing. Two years later, Fuller completed the Dymaxion House, that could be mass-produced and easily dismantled and transported to another location, whenever it’s owner wished to relocate. In 1922, Fuller’s daughter Alexandra died from polio, which was a turning point in Fuller’s life, as he blamed himself for her dead and started drinking excessively. Despite Fuller’s revolutionizing inventions in the building sector he went bankruptcy in 1927, soon after his business with his father-in-law had failed.

Buckminster Fuller spent the next fifteen years with several projects and collaborations until he started teaching at the Black Mountain College, NC. During the time Fuller served as a Summer Institute director in college he formed a group of students and other professors, inclusively Kenneth Snelson and started to reinvent the dome that was designed by Walther Bauersfeld, just after WWI. Fuller advanced the idea of the dome and developed its intrinsic mathematics in collaboration with Snelson. The dome that Buckminster Fuller named “geodesic” received the U.S. patent in 1954, earned him international recognition and started to dominate his further career, as the U.S. Government employed Fuller’s firm to construct domes for the U.S. army.

The outstanding reputation Fuller earned with his Geodesic Dome allowed him to lecture at various well-known Universities around the world and gained him full professorship in 1968. Fuller’s outstanding contributions earned him various awards, such as the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Buckminster Fuller’s Life

I’ve chosen to include some very inspiring anecdotes of Fuller’s life, as I found it appropriate to also point out what a strong character and will power he had.

Fuller studied at Harvard and his life was like everyone else’s, he spend his spare-time partying and football and was expelled twice from Harvard, as he “lacked interest”. The event that changed Fuller’s life forever was the death of his daughter Alexandra. After his kid had died in his arms he started drinking heavily and – as the story tells – decided to end his life. Nevertheless, his inner voice told him not to do so as he hadn’t fulfilled the purpose of his life, yet, which made him eager to seek for what efforts he – as a broke man without power and money – could do on the behalf of humanity. During his longstanding search he discovered some of the principles of the universe, that he named the “Generalised Principles”, that can be found in his books “Synergetics” and included his attempts to make a positive difference in the world and to increase the happiness in his life and of the people he was living with.

Thes Success Stories of the following people might also interest you:

- Ferdinant Porsche

- Enzo Ferrari

- Ferruccio Lamborghini

How does the success story of Buckminster Fuller inspire your own actions?

About Author

Steve is the founder of Planet of Success, the #1 choice when it comes to motivation, self-growth and empowerment. This world does not need followers. What it needs is people who stand in their own sovereignty. Join us in the quest to live life to the fullest!

Richard Buckminster Fuller (; July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983)[1] was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing more than 30 books and coining or popularizing such terms as «Spaceship Earth», «Dymaxion» (e.g., Dymaxion house, Dymaxion car, Dymaxion map), «ephemeralization», «synergetics», and «tensegrity».

|

Buckminster Fuller |

|

|---|---|

Fuller in 1972 |

|

| Born |

Richard Buckminster Fuller July 12, 1895 Milton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 1983 (aged 87)

Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse |

Anne Hewlett (m. 1917) |

| Children | Allegra Fuller Snyder |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1983) |

| Buildings | Geodesic dome (1940s) |

| Projects | Dymaxion house (1928) |

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Education | Harvard University (expelled) |

| Notable work |

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy

|

|

Notable ideas |

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

Fuller developed numerous inventions, mainly architectural designs, and popularized the widely known geodesic dome; carbon molecules known as fullerenes were later named by scientists for their structural and mathematical resemblance to geodesic spheres. He also served as the second World President of Mensa International from 1974 to 1983.[2][3]

Fuller was awarded 28 United States patents[4] and many honorary doctorates. In 1960, he was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medal from The Franklin Institute. He was elected an honorary member of Phi Beta Kappa in 1967, on the occasion of the 50-year reunion of his Harvard class of 1917 (from which he was expelled in his first year).[5][6] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1968.[7] The same year, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member. He became a full Academician in 1970, and he received the Gold Medal award from the American Institute of Architects the same year. In 1976, he received the St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates.[8][9] In 1977, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[10] He also received numerous other awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, presented to him on February 23, 1983, by President Ronald Reagan.

Life and workEdit

Fuller was born on July 12, 1895, in Milton, Massachusetts, the son of Richard Buckminster Fuller and Caroline Wolcott Andrews, and grand-nephew of Margaret Fuller, an American journalist, critic, and women’s rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movement. The unusual middle name, Buckminster, was an ancestral family name. As a child, Richard Buckminster Fuller tried numerous variations of his name. He used to sign his name differently each year in the guest register of his family summer vacation home at Bear Island, Maine. He finally settled on R. Buckminster Fuller.[11]

Fuller spent much of his youth on Bear Island, in Penobscot Bay off the coast of Maine. He attended Froebelian Kindergarten.[12] He was dissatisfied with the way geometry was taught in school, disagreeing with the notions that a chalk dot on the blackboard represented an «empty» mathematical point, or that a line could stretch off to infinity. To him these were illogical, and led to his work on synergetics. He often made items from materials he found in the woods, and sometimes made his own tools. He experimented with designing a new apparatus for human propulsion of small boats. By age 12, he had invented a ‘push pull’ system for propelling a rowboat by use of an inverted umbrella connected to the transom with a simple oar lock which allowed the user to face forward to point the boat toward its destination. Later in life, Fuller took exception to the term «invention».

Years later, he decided that this sort of experience had provided him with not only an interest in design, but also a habit of being familiar with and knowledgeable about the materials that his later projects would require. Fuller earned a machinist’s certification, and knew how to use the press brake, stretch press, and other tools and equipment used in the sheet metal trade.[13]

EducationEdit

Fuller attended Milton Academy in Massachusetts, and after that began studying at Harvard College, where he was affiliated with Adams House. He was expelled from Harvard twice: first for spending all his money partying with a vaudeville troupe, and then, after having been readmitted, for his «irresponsibility and lack of interest». By his own appraisal, he was a non-conforming misfit in the fraternity environment.[13]

Wartime experienceEdit

Between his sessions at Harvard, Fuller worked in Canada as a mechanic in a textile mill, and later as a laborer in the meat-packing industry. He also served in the U.S. Navy in World War I, as a shipboard radio operator, as an editor of a publication, and as commander of the crash rescue boat USS Inca. After discharge, he worked again in the meat-packing industry, acquiring management experience. In 1917, he married Anne Hewlett. During the early 1920s, he and his father-in-law developed the Stockade Building System for producing lightweight, weatherproof, and fireproof housing—although the company would ultimately fail[13] in 1927.[14]

Depression and epiphanyEdit

Buckminster Fuller recalled 1927 as a pivotal year of his life. His daughter Alexandra had died in 1922 of complications from polio and spinal meningitis[15] just before her fourth birthday.[16] Barry Katz, a Stanford University scholar who wrote about Fuller, found signs that around this time in his life Fuller was suffering from depression and anxiety.[17] Fuller dwelled on his daughter’s death, suspecting that it was connected with the Fullers’ damp and drafty living conditions.[16] This provided motivation for Fuller’s involvement in Stockade Building Systems, a business which aimed to provide affordable, efficient housing.[16]

In 1927, at age 32, Fuller lost his job as president of Stockade. The Fuller family had no savings, and the birth of their daughter Allegra in 1927 added to the financial challenges. Fuller drank heavily and reflected upon the solution to his family’s struggles on long walks around Chicago. During the autumn of 1927, Fuller contemplated suicide by drowning in Lake Michigan, so that his family could benefit from a life insurance payment.[18]

Fuller said that he had experienced a profound incident which would provide direction and purpose for his life. He felt as though he was suspended several feet above the ground enclosed in a white sphere of light. A voice spoke directly to Fuller, and declared:

From now on you need never await temporal attestation to your thought. You think the truth. You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the Universe. Your significance will remain forever obscure to you, but you may assume that you are fulfilling your role if you apply yourself to converting your experiences to the highest advantage of others.[19]

Fuller stated that this experience led to a profound re-examination of his life. He ultimately chose to embark on «an experiment, to find what a single individual could contribute to changing the world and benefiting all humanity».[20]

Speaking to audiences later in life, Fuller would regularly recount the story of his Lake Michigan experience, and its transformative impact on his life.

RecoveryEdit

In 1927 Fuller resolved to think independently which included a commitment to «the search for the principles governing the universe and help advance the evolution of humanity in accordance with them … finding ways of doing more with less to the end that all people everywhere can have more and more».[citation needed] By 1928, Fuller was living in Greenwich Village and spending much of his time at the popular café Romany Marie’s,[21] where he had spent an evening in conversation with Marie and Eugene O’Neill several years earlier.[22] Fuller accepted a job decorating the interior of the café in exchange for meals,[21] giving informal lectures several times a week,[22][23] and models of the Dymaxion house were exhibited at the café. Isamu Noguchi arrived during 1929—Constantin Brâncuși, an old friend of Marie’s,[24] had directed him there[21]—and Noguchi and Fuller were soon collaborating on several projects,[23][25] including the modeling of the Dymaxion car based on recent work by Aurel Persu.[26] It was the beginning of their lifelong friendship.

Geodesic domesEdit

Fuller taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina during the summers of 1948 and 1949,[27] serving as its Summer Institute director in 1949. Fuller had been shy and withdrawn, but he was persuaded to participate in a theatrical performance of Erik Satie’s Le piège de Méduse produced by John Cage, who was also teaching at Black Mountain. During rehearsals, under the tutelage of Arthur Penn, then a student at Black Mountain, Fuller broke through his inhibitions to become confident as a performer and speaker.[28]

At Black Mountain, with the support of a group of professors and students, he began reinventing a project that would make him famous: the geodesic dome. Although the geodesic dome had been created, built and awarded a German patent on June 19, 1925 by Dr. Walther Bauersfeld, Fuller was awarded United States patents. Fuller’s patent application made no mention of Bauersfeld’s self-supporting dome built some 26 years prior. Although Fuller undoubtedly popularized this type of structure he is mistakenly given credit for its design.

One of his early models was first constructed in 1945 at Bennington College in Vermont, where he lectured often. Although Bauersfeld’s dome could support a full skin of concrete it was not until 1949 that Fuller erected a geodesic dome building that could sustain its own weight with no practical limits. It was 4.3 meters (14 feet) in diameter and constructed of aluminium aircraft tubing and a vinyl-plastic skin, in the form of an icosahedron. To prove his design, Fuller suspended from the structure’s framework several students who had helped him build it. The U.S. government recognized the importance of this work, and employed his firm Geodesics, Inc. in Raleigh, North Carolina to make small domes for the Marines. Within a few years, there were thousands of such domes around the world.

Fuller’s first «continuous tension – discontinuous compression» geodesic dome (full sphere in this case) was constructed at the University of Oregon Architecture School in 1959 with the help of students.[29] These continuous tension – discontinuous compression structures featured single force compression members (no flexure or bending moments) that did not touch each other and were ‘suspended’ by the tensional members.

Dymaxion ChronofileEdit

A 1933 Dymaxion prototype.

For half of a century, Fuller developed many ideas, designs and inventions, particularly regarding practical, inexpensive shelter and transportation. He documented his life, philosophy and ideas scrupulously by a daily diary (later called the Dymaxion Chronofile), and by twenty-eight publications. Fuller financed some of his experiments with inherited funds, sometimes augmented by funds invested by his collaborators, one example being the Dymaxion car project.

World stageEdit

International recognition began with the success of huge geodesic domes during the 1950s. Fuller lectured at North Carolina State University in Raleigh in 1949, where he met James Fitzgibbon, who would become a close friend and colleague. Fitzgibbon was director of Geodesics, Inc. and Synergetics, Inc. the first licensees to design geodesic domes. Thomas C. Howard was lead designer, architect and engineer for both companies. Richard Lewontin, a new faculty member in population genetics at North Carolina State University, provided Fuller with computer calculations for the lengths of the domes’ edges.[30]

Fuller began working with architect Shoji Sadao[31] in 1954, together designing a hypothetical Dome over Manhattan in 1960, and in 1964 they co-founded the architectural firm Fuller & Sadao Inc., whose first project was to design the large geodesic dome for the U.S. Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal.[31] This building is now the «Montreal Biosphère».

In 1962, the artist and searcher John McHale wrote the first monograph on Fuller, published by George Braziller in New York.

After employing several Southern Illinois University Carbondale graduate students to rebuild his models following an apartment fire in the summer of 1959, Fuller was recruited by longtime friend Harold Cohen to serve as a research professor of «design science exploration» at the institution’s School of Art and Design. According to SIU architecture professor Jon Davey, the position was «unlike most faculty appointments … more a celebrity role than a teaching job» in which Fuller offered few courses and was only stipulated to spend two months per year on campus.[32] Nevertheless, his time in Carbondale was «extremely productive», and Fuller was promoted to university professor in 1968 and distinguished university professor in 1972.[33][32]

Working as a designer, scientist, developer, and writer, he continued to lecture for many years around the world. He collaborated at SIU with John McHale. In 1965, they inaugurated the World Design Science Decade (1965 to 1975) at the meeting of the International Union of Architects in Paris, which was, in Fuller’s own words, devoted to «applying the principles of science to solving the problems of humanity.»

From 1972 until retiring as university professor emeritus in 1975, Fuller held a joint appointment at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, where he had designed the dome for the campus Religious Center in 1971.[34] During this period, he also held a joint fellowship at a consortium of Philadelphia-area institutions, including the University of Pennsylvania, Bryn Mawr College, Haverford College, Swarthmore College and the University City Science Center; as a result of this affiliation, the University of Pennsylvania appointed him university professor emeritus in 1975.[33]

Fuller believed human societies would soon rely mainly on renewable sources of energy, such as solar- and wind-derived electricity. He hoped for an age of «omni-successful education and sustenance of all humanity». Fuller referred to himself as «the property of universe» and during one radio interview he gave later in life, declared himself and his work «the property of all humanity». For his lifetime of work, the American Humanist Association named him the 1969 Humanist of the Year.

In 1976, Fuller was a key participant at UN Habitat I, the first UN forum on human settlements.

Last filmed appearanceEdit

Fuller’s last filmed interview took place on June 21, 1983, in which he spoke at Norman Foster’s Royal Gold Medal for architecture ceremony.[35] His speech can be watched in the archives of the AA School of Architecture, in which he spoke after Sir Robert Sainsbury’s introductory speech and Foster’s keynote address.

DeathEdit

In the year of his death, Fuller described himself as follows:

Guinea Pig B:

I AM NOW CLOSE TO 88 and I am confident that the only thing important about me is that I am an average healthy human. I am also a living case history of a thoroughly documented, half-century, search-and-research project designed to discover what, if anything, an unknown, moneyless individual, with a dependent wife and newborn child, might be able to do effectively on behalf of all humanity that could not be accomplished by great nations, great religions or private enterprise, no matter how rich or powerfully armed.[36]

Fuller died on July 1, 1983, 11 days before his 88th birthday. During the period leading up to his death, his wife had been lying comatose in a Los Angeles hospital, dying of cancer. It was while visiting her there that he exclaimed, at a certain point: «She is squeezing my hand!» He then stood up, suffered a heart attack, and died an hour later, at age 87. His wife of 66 years died 36 hours later. They are buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

PhilosophyEdit

Buckminster Fuller was a Unitarian, and, like his grandfather Arthur Buckminster Fuller (brother of Margaret Fuller),[37][38] a Unitarian minister. Fuller was also an early environmental activist, aware of Earth’s finite resources, and promoted a principle he termed «ephemeralization», which, according to futurist and Fuller disciple Stewart Brand, was defined as «doing more with less».[39] Resources and waste from crude, inefficient products could be recycled into making more valuable products, thus increasing the efficiency of the entire process. Fuller also coined the word synergetics, a catch-all term used broadly for communicating experiences using geometric concepts, and more specifically, the empirical study of systems in transformation; his focus was on total system behavior unpredicted by the behavior of any isolated components.

Fuller was a pioneer in thinking globally, and explored energy and material efficiency in the fields of architecture, engineering and design.[40][41] In his book Critical Path (1981) he cited the opinion of François de Chadenèdes[42] (1920-1999) that petroleum, from the standpoint of its replacement cost in our current energy «budget» (essentially, the net incoming solar flux), had cost nature «over a million dollars» per U.S. gallon ($300,000 per litre) to produce. From this point of view, its use as a transportation fuel by people commuting to work represents a huge net loss compared to their actual earnings.[43] An encapsulation quotation of his views might best be summed up as: «There is no energy crisis, only a crisis of ignorance.»[44][45][46]

Though Fuller was concerned about sustainability and human survival under the existing socioeconomic system, he remained optimistic about humanity’s future. Defining wealth in terms of knowledge, as the «technological ability to protect, nurture, support, and accommodate all growth needs of life», his analysis of the condition of «Spaceship Earth» caused him to conclude that at a certain time during the 1970s, humanity had attained an unprecedented state. He was convinced that the accumulation of relevant knowledge, combined with the quantities of major recyclable resources that had already been extracted from the earth, had attained a critical level, such that competition for necessities had become unnecessary. Cooperation had become the optimum survival strategy. He declared: «selfishness is unnecessary and hence-forth unrationalizable … War is obsolete.»[47] He criticized previous utopian schemes as too exclusive, and thought this was a major source of their failure. To work, he thought that a utopia needed to include everyone.[48]

Fuller was influenced by Alfred Korzybski’s idea of general semantics. In the 1950s, Fuller attended seminars and workshops organized by the Institute of General Semantics, and he delivered the annual Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture in 1955.[49] Korzybski is mentioned in the Introduction of his book Synergetics. The two shared a remarkable amount of similarity in their formulations of general semantics.[50]

In his 1970 book I Seem To Be a Verb, he wrote: «I live on Earth at present, and I don’t know what I am. I know that I am not a category. I am not a thing—a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process—an integral function of the universe.»

Fuller wrote that the natural analytic geometry of the universe was based on arrays of tetrahedra. He developed this in several ways, from the close-packing of spheres and the number of compressive or tensile members required to stabilize an object in space. One confirming result was that the strongest possible homogeneous truss is cyclically tetrahedral.[51]

He had become a guru of the design, architecture, and «alternative» communities, such as Drop City, the community of experimental artists to whom he awarded the 1966 «Dymaxion Award» for «poetically economic» domed living structures.

Major design projectsEdit

The geodesic domeEdit

Fuller was most famous for his lattice shell structures – geodesic domes, which have been used as parts of military radar stations, civic buildings, environmental protest camps and exhibition attractions. An examination of the geodesic design by Walther Bauersfeld for the Zeiss-Planetarium, built some 28 years prior to Fuller’s work, reveals that Fuller’s Geodesic Dome patent (U.S. 2,682,235; awarded in 1954) is the same design as Bauersfeld’s.[52]

Their construction is based on extending some basic principles to build simple «tensegrity» structures (tetrahedron, octahedron, and the closest packing of spheres), making them lightweight and stable. The geodesic dome was a result of Fuller’s exploration of nature’s constructing principles to find design solutions. The Fuller Dome is referenced in the Hugo Award-winning novel Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner, in which a geodesic dome is said to cover the entire island of Manhattan, and it floats on air due to the hot-air balloon effect of the large air-mass under the dome (and perhaps its construction of lightweight materials).[53]

TransportationEdit

The Omni-Media-Transport:

With such a vehicle at our disposal, [Fuller] felt that human travel, like that of birds, would no longer be confined to airports, roads, and other bureaucratic boundaries, and that autonomous free-thinking human beings could live and prosper wherever they chose.[54]

—Lloyd S. Sieden, Bucky Fuller’s Universe, 2000

To his young daughter Allegra:

Fuller described the Dymaxion as a «zoom-mobile, explaining that it could hop off the road at will, fly about, then, as deftly as a bird, settle back into a place in traffic».[55]

The Dymaxion car, c.1933, artist Diego Rivera shown entering the car, carrying coat.

The Dymaxion car was a vehicle designed by Fuller, featured prominently at Chicago’s 1933-1934 Century of Progress World’s Fair.[56] During the Great Depression, Fuller formed the Dymaxion Corporation and built three prototypes with noted naval architect Starling Burgess and a team of 27 workmen — using donated money as well as a family inheritance.[57][58]

Fuller associated the word Dymaxion, a blend of the words dynamic, maximum, and tension[59] to sum up the goal of his study, «maximum gain of advantage from minimal energy input».[60]

The Dymaxion was not an automobile but rather the ‘ground-taxying mode’ of a vehicle that might one day be designed to fly, land and drive — an «Omni-Medium Transport» for air, land and water.[61] Fuller focused on the landing and taxiing qualities, and noted severe limitations in its handling. The team made improvements and refinements to the platform,[54] and Fuller noted the Dymaxion «was an invention that could not be made available to the general public without considerable improvements».[54]

The bodywork was aerodynamically designed for increased fuel efficiency and its platform featured a lightweight cromoly-steel hinged chassis, rear-mounted V8 engine, front-drive and three-wheels. The vehicle was steered via the third wheel at the rear, capable of 90° steering lock. Able to steer in a tight circle, the Dymaxion often caused a sensation, bringing nearby traffic to a halt.[62][63]

Shortly after launch, a prototype rolled over and crashed, killing the Dymaxion’s driver and seriously injuring its passengers.[64] Fuller blamed the accident on a second car that collided with the Dymaxion.[65] [66] Eyewitnesses reported, however, that the other car hit the Dymaxion only after it had begun to roll over.[64]

Despite courting the interest of important figures from the auto industry, Fuller used his family inheritance to finish the second and third prototypes[67] — eventually selling all three, dissolving Dymaxion Corporation and maintaining the Dymaxion was never intended as a commercial venture.[68] One of the three original prototypes survives.[69]

HousingEdit

Fuller’s energy-efficient and inexpensive Dymaxion house garnered much interest, but only two prototypes were ever produced. Here the term «Dymaxion» is used in effect to signify a «radically strong and light tensegrity structure». One of Fuller’s Dymaxion Houses is on display as a permanent exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. Designed and developed during the mid-1940s, this prototype is a round structure (not a dome), shaped something like the flattened «bell» of certain jellyfish. It has several innovative features, including revolving dresser drawers, and a fine-mist shower that reduces water consumption. According to Fuller biographer Steve Crooks, the house was designed to be delivered in two cylindrical packages, with interior color panels available at local dealers. A circular structure at the top of the house was designed to rotate around a central mast to use natural winds for cooling and air circulation.

Conceived nearly two decades earlier, and developed in Wichita, Kansas, the house was designed to be lightweight, adapted to windy climates, cheap to produce and easy to assemble. Because of its light weight and portability, the Dymaxion House was intended to be the ideal housing for individuals and families who wanted the option of easy mobility.[70] The design included a «Go-Ahead-With-Life Room» stocked with maps, charts, and helpful tools for travel «through time and space».[71] It was to be produced using factories, workers, and technologies that had produced World War II aircraft. It looked ultramodern at the time, built of metal, and sheathed in polished aluminum. The basic model enclosed 90 m2 (970 sq ft) of floor area. Due to publicity, there were many orders during the early Post-War years, but the company that Fuller and others had formed to produce the houses failed due to management problems.

In 1967, Fuller developed a concept for an offshore floating city named Triton City and published a report on the design the following year.[72] Models of the city aroused the interest of President Lyndon B. Johnson who, after leaving office, had them placed in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum.[73]

In 1969, Fuller began the Otisco Project, named after its location in Otisco, New York. The project developed and demonstrated concrete spray with mesh-covered wireforms for producing large-scale, load-bearing spanning structures built on-site, without the use of pouring molds, other adjacent surfaces or hoisting. The initial method used a circular concrete footing in which anchor posts were set. Tubes cut to length and with ends flattened were then bolted together to form a duodeca-rhombicahedron (22-sided hemisphere) geodesic structure with spans ranging to 60 feet (18 m). The form was then draped with layers of ¼-inch wire mesh attached by twist ties. Concrete was sprayed onto the structure, building up a solid layer which, when cured, would support additional concrete to be added by a variety of traditional means. Fuller referred to these buildings as monolithic ferroconcrete geodesic domes. However, the tubular frame form proved problematic for setting windows and doors. It was replaced by an iron rebar set vertically in the concrete footing and then bent inward and welded in place to create the dome’s wireform structure and performed satisfactorily. Domes up to three stories tall built with this method proved to be remarkably strong. Other shapes such as cones, pyramids and arches proved equally adaptable.

The project was enabled by a grant underwritten by Syracuse University and sponsored by U.S. Steel (rebar), the Johnson Wire Corp, (mesh) and Portland Cement Company (concrete). The ability to build large complex load bearing concrete spanning structures in free space would open many possibilities in architecture, and is considered one of Fuller’s greatest contributions.

Dymaxion map and World GameEdit

Fuller, along with co-cartographer Shoji Sadao, also designed an alternative projection map, called the Dymaxion map. This was designed to show Earth’s continents with minimum distortion when projected or printed on a flat surface.

In the 1960s, Fuller developed the World Game, a collaborative simulation game played on a 70-by-35-foot Dymaxion map,[74] in which players attempt to solve world problems.[75][76] The object of the simulation game is, in Fuller’s words, to «make the world work, for 100% of humanity, in the shortest possible time, through spontaneous cooperation, without ecological offense or the disadvantage of anyone».[77]

Appearance and styleEdit

Buckminster Fuller wore thick-lensed spectacles to correct his extreme hyperopia, a condition that went undiagnosed for the first five years of his life.[78] Fuller’s hearing was damaged during his Naval service in World War I and deteriorated during the 1960s.[79] After experimenting with bullhorns as hearing aids during the mid-1960s,[79] Fuller adopted electronic hearing aids from the 1970s onward.[16]: 397

In public appearances, Fuller always wore dark-colored suits, appearing like «an alert little clergyman».[80]: 18 Previously, he had experimented with unconventional clothing immediately after his 1927 epiphany, but found that breaking social fashion customs made others devalue or dismiss his ideas.[81]: 6:15 Fuller learned the importance of physical appearance as part of one’s credibility, and decided to become «the invisible man» by dressing in clothes that would not draw attention to himself.[81]: 6:15 With self-deprecating humor, Fuller described this black-suited appearance as resembling a «second-rate bank clerk».[81]: 6:15

Writer Guy Davenport met him in 1965 and described him thus:

He’s a dwarf, with a worker’s hands, all callouses and squared fingers. He carries an ear trumpet, of green plastic, with WORLD SERIES 1965 printed on it. His smile is golden and frequent; the man’s temperament is angelic, and his energy is just a touch more than that of [Robert] Gallway (champeen runner, footballeur, and swimmer). One leg is shorter than the other, and the prescription shoe worn to correct the imbalance comes from a country doctor deep in the wilderness of Maine. Blue blazer, Khrushchev trousers, and a briefcase full of Japanese-made wonderments;[82]

LifestyleEdit

Following his global prominence from the 1960s onward, Fuller became a frequent flier, often crossing time zones to lecture. In the 1960s and 1970s, he wore three watches simultaneously; one for the time zone of his office at Southern Illinois University, one for the time zone of the location he would next visit, and one for the time zone he was currently in.[80]: 290 [83][84] In the 1970s, Fuller was only in ‘homely’ locations (his personal home in Carbondale, Illinois; his holiday retreat in Bear Island, Maine; and his daughter’s home in Pacific Palisades, California) roughly 65 nights per year—the other 300 nights were spent in hotel beds in the locations he visited on his lecturing and consulting circuits.[80]: 290

In the 1920s, Fuller experimented with polyphasic sleep, which he called Dymaxion sleep. Inspired by the sleep habits of animals such as dogs and cats,[85]: 133 Fuller worked until he was tired, and then slept short naps. This generally resulted in Fuller sleeping 30-minute naps every 6 hours.[80]: 160 This allowed him «twenty-two thinking hours a day», which aided his work productivity.[80]: 160 Fuller reportedly kept this Dymaxion sleep habit for two years, before quitting the routine because it conflicted with his business associates’ sleep habits.[86] Despite no longer personally partaking in the habit, in 1943 Fuller suggested Dymaxion sleep as a strategy that the United States could adopt to win World War II.[86]

Despite only practicing true polyphasic sleep for a period during the 1920s, Fuller was known for his stamina throughout his life. He was described as «tireless»[87]: 53 by Barry Farrell in Life magazine, who noted that Fuller stayed up all night replying to mail during Farrell’s 1970 trip to Bear Island.[87]: 55 In his seventies, Fuller generally slept for 5–8 hours per night.[80]: 160

Fuller documented his life copiously from 1915 to 1983, approximately 270 feet (82 m) of papers in a collection called the Dymaxion Chronofile. He also kept copies of all incoming and outgoing correspondence. The enormous R. Buckminster Fuller Collection is currently housed at Stanford University.[88]

If somebody kept a very accurate record of a human being, going through the era from the Gay 90s, from a very different kind of world through the turn of the century—as far into the twentieth century as you might live. I decided to make myself a good case history of such a human being and it meant that I could not be judge of what was valid to put in or not. I must put everything in, so I started a very rigorous record.[89][90]

Language and neologismsEdit

Buckminster Fuller spoke and wrote in a unique style and said it was important to describe the world as accurately as possible.[91] Fuller often created long run-on sentences and used unusual compound words (omniwell-informed, intertransformative, omni-interaccommodative, omniself-regenerative) as well as terms he himself invented.[92] His style of speech was characterized by progressively rapid and breathless delivery and rambling digressions of thought, which Fuller described as «thinking out loud». The effect, combined with Fuller’s dry voice and non-rhotic New England accent, was varyingly considered «hypnotic» or «overwhelming».

Fuller used the word Universe without the definite or indefinite article (the or an) and always capitalized the word. Fuller wrote that «by Universe I mean: the aggregate of all humanity’s consciously apprehended and communicated (to self or others) Experiences».[93]

The words «down» and «up», according to Fuller, are awkward in that they refer to a planar concept of direction inconsistent with human experience. The words «in» and «out» should be used instead, he argued, because they better describe an object’s relation to a gravitational center, the Earth. «I suggest to audiences that they say, ‘I’m going «outstairs» and «instairs.»‘ At first that sounds strange to them; They all laugh about it. But if they try saying in and out for a few days in fun, they find themselves beginning to realize that they are indeed going inward and outward in respect to the center of Earth, which is our Spaceship Earth. And for the first time they begin to feel real ‘reality.'»[94]

«World-around» is a term coined by Fuller to replace «worldwide». The general belief in a flat Earth died out in classical antiquity, so using «wide» is an anachronism when referring to the surface of the Earth—a spheroidal surface has area and encloses a volume but has no width. Fuller held that unthinking use of obsolete scientific ideas detracts from and misleads intuition. Other neologisms collectively invented by the Fuller family, according to Allegra Fuller Snyder, are the terms «sunsight» and «sunclipse», replacing «sunrise» and «sunset» to overturn the geocentric bias of most pre-Copernican celestial mechanics.

Fuller also invented the word «livingry», as opposed to weaponry (or «killingry»), to mean that which is in support of all human, plant, and Earth life. «The architectural profession—civil, naval, aeronautical, and astronautical—has always been the place where the most competent thinking is conducted regarding livingry, as opposed to weaponry.»[95]

As well as contributing significantly to the development of tensegrity technology, Fuller invented the term «tensegrity», a portmanteau of «tensional integrity». «Tensegrity describes a structural-relationship principle in which structural shape is guaranteed by the finitely closed, comprehensively continuous, tensional behaviors of the system and not by the discontinuous and exclusively local compressional member behaviors. Tensegrity provides the ability to yield increasingly without ultimately breaking or coming asunder.»[96]

«Dymaxion» is a portmanteau of «dynamic maximum tension». It was invented around 1929 by two admen at Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago to describe Fuller’s concept house, which was shown as part of a house of the future store display. They created the term using three words that Fuller used repeatedly to describe his design – dynamic, maximum, and tension.[97]

Fuller also helped to popularize the concept of Spaceship Earth: «The most important fact about Spaceship Earth: an instruction manual didn’t come with it.»[98]

In the preface for his «cosmic fairy tale» Tetrascroll: Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Fuller stated that his distinctive speaking style grew out of years of embellishing the classic tale for the benefit of his daughter, allowing him to explore both his new theories and how to present them. The Tetrascroll narrative was eventually transcribed onto a set of tetrahedral lithographs (hence the name), as well as being published as a traditional book.

Concepts and buildingsEdit

His concepts and buildings include:

|

|

Influence and legacyEdit

Among the many people who were influenced by Buckminster Fuller are:

Constance Abernathy,[104]Ruth Asawa,[105]J. Baldwin,[106][107]

Michael Ben-Eli,[108] Pierre Cabrol,[109]John Cage,

Joseph Clinton,[110]

Peter Floyd,[108]Norman Foster,[111][112]Medard Gabel,[113]

Michael Hays,[108]Ted Nelson,[114]David Johnston,[115]Peter Jon Pearce,[108]Shoji Sadao,[108]Edwin Schlossberg,[108]Kenneth Snelson,[105][116][117]Robert Anton Wilson,[118] Stewart Brand,[119] and Jason McLennan.[120]

An allotrope of carbon, fullerene—and a particular molecule of that allotrope C60 (buckminsterfullerene or buckyball) has been named after him. The Buckminsterfullerene molecule, which consists of 60 carbon atoms, very closely resembles a spherical version of Fuller’s geodesic dome. The 1996 Nobel prize in chemistry was given to Kroto, Curl, and Smalley for their discovery of the fullerene.[121]

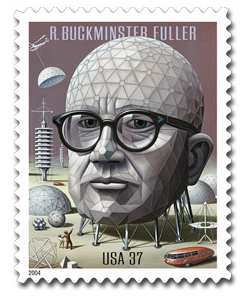

On July 12, 2004, the United States Post Office released a new commemorative stamp honoring R. Buckminster Fuller on the 50th anniversary of his patent for the geodesic dome and by the occasion of his 109th birthday. The stamp’s design replicated the January 10, 1964, cover of Time magazine.

Fuller was the subject of two documentary films: The World of Buckminster Fuller (1971) and Buckminster Fuller: Thinking Out Loud (1996). Additionally, filmmaker Sam Green and the band Yo La Tengo collaborated on a 2012 «live documentary» about Fuller, The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller.[122]

In June 2008, the Whitney Museum of American Art presented «Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe», the most comprehensive retrospective to date of his work and ideas.[123] The exhibition traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago in 2009. It presented a combination of models, sketches, and other artifacts, representing six decades of the artist’s integrated approach to housing, transportation, communication, and cartography. It also featured the extensive connections with Chicago from his years spent living, teaching, and working in the city.[124]

In 2009, a number of US companies decided to repackage spherical magnets and sell them as toys. One company, Maxfield & Oberton, told The New York Times that they saw the product on YouTube and decided to repackage them as «Buckyballs«, because the magnets could self-form and hold together in shapes reminiscent of the Fuller inspired buckyballs.[125] The buckyball toy launched at New York International Gift Fair in 2009 and sold in the hundreds of thousands, but by 2010 began to experience problems with toy safety issues and the company was forced to recall the packages that were labelled as toys.[126]

In 2012, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art hosted «The Utopian Impulse» – a show about Buckminster Fuller’s influence in the Bay Area. Featured were concepts, inventions and designs for creating «free energy» from natural forces, and for sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. The show ran January through July.[127]

In popular cultureEdit

Fuller is quoted in «The Tower of Babble» from the musical Godspell: «Man is a complex of patterns and processes.»[128]

Belgian rock band dEUS released the song The Architect, inspired by Fuller, on their 2008 album Vantage Point.[129]

Indie band Driftless Pony Club titled their 2011 album Buckminster after Fuller.[130] Each of the album’s songs is based upon his life and works.

The design podcast 99% Invisible (2010–present) takes its title from a Fuller quote: «Ninety-nine percent of who you are is invisible and untouchable.»[131]

Fuller is briefly mentioned in X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014) when Kitty Pryde is giving a lecture to a group of students regarding utopian architecture.[132]

Robert Kiyosaki’s 2015 book Second Chance[133] concerns Kiyosaki’s interactions with Fuller as well as Fuller’s unusual final book, Grunch of Giants.[134]

In The House of Tomorrow (2017), based on Peter Bognanni’s 2010 novel of the same name, Ellen Burstyn’s character is obsessed with Fuller and provides retro-futurist tours of her geodesic home that include videos of Fuller sailing and talking with Burstyn, who had in real life befriended Fuller.

PatentsEdit

(from the Table of Contents of Inventions: The Patented Works of R. Buckminster Fuller (1983) ISBN 0-312-43477-4)

- 1927 U.S. Patent 1,633,702 Stockade: building structure

- 1927 U.S. Patent 1,634,900 Stockade: pneumatic forming process

- 1928 (Application Abandoned) 4D house

- 1937 U.S. Patent 2,101,057 Dymaxion car

- 1940 U.S. Patent 2,220,482 Dymaxion bathroom

- 1944 U.S. Patent 2,343,764 Dymaxion deployment unit (sheet)

- 1944 U.S. Patent 2,351,419 Dymaxion deployment unit (frame)

- 1946 U.S. Patent 2,393,676 Dymaxion map

- 1946 (No Patent) Dymaxion house (Wichita)

- 1954 U.S. Patent 2,682,235 Geodesic dome

- 1959 U.S. Patent 2,881,717 Paperboard dome

- 1959 U.S. Patent 2,905,113 Plydome

- 1959 U.S. Patent 2,914,074 Catenary (geodesic tent)

- 1961 U.S. Patent 2,986,241 Octet truss

- 1962 U.S. Patent 3,063,521 Tensegrity

- 1963 U.S. Patent 3,080,583 Submarisle (undersea island)

- 1964 U.S. Patent 3,139,957 Aspension (suspension building)

- 1965 U.S. Patent 3,197,927 Monohex (geodesic structures)

- 1965 U.S. Patent 3,203,144 Laminar dome

- 1965 (Filed – No Patent) Octa spinner

- 1967 U.S. Patent 3,354,591 Star tensegrity (octahedral truss)

- 1970 U.S. Patent 3,524,422 Rowing needles (watercraft)

- 1974 U.S. Patent 3,810,336 Geodesic hexa-pent

- 1975 U.S. Patent 3,863,455 Floatable breakwater

- 1975 U.S. Patent 3,866,366 Non-symmetrical tensegrity

- 1979 U.S. Patent 4,136,994 Floating breakwater

- 1980 U.S. Patent 4,207,715 Tensegrity truss

- 1983 U.S. Patent 4,377,114 Hanging storage shelf unit

BibliographyEdit

- 4d Timelock (1928)

- Nine Chains to the Moon (1938)

- Untitled Epic Poem on the History of Industrialization (1962)

- Ideas and Integrities, a Spontaneous Autobiographical Disclosure (1963) ISBN 0-13-449140-8

- No More Secondhand God and Other Writings (1963)

- Education Automation: Freeing the Scholar to Return (1963)

- What I Have Learned: A Collection of 20 Autobiographical Essays, Chapter «How Little I Know», (1968)

- Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1968) ISBN 0-8093-2461-X

- Utopia or Oblivion (1969) ISBN 0-553-02883-9

- Approaching the Benign Environment (1970) ISBN 0-8173-6641-5 (with Eric A. Walker and James R. Killian, Jr.)

- I Seem to Be a Verb (1970) coauthors Jerome Agel, Quentin Fiore, ISBN 1-127-23153-7

- Intuition (1970)

- Buckminster Fuller to Children of Earth (1972) compiled and photographed by Cam Smith, ISBN 0-385-02979-9

- The Buckminster Fuller Reader (1972) editor James Meller, ISBN 978-0140214345

- The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller (1960, 1973) coauthor Robert Marks, ISBN 0-385-01804-5

- Earth, Inc (1973) ISBN 0-385-01825-8

- Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking (1975) in collaboration with E.J. Applewhite with a preface and contribution by Arthur L. Loeb, ISBN 0-02-541870-X

- Tetrascroll: Goldilocks and the Three Bears, A Cosmic Fairy Tale (1975)

- And It Came to Pass — Not to Stay (1976) ISBN 0-02-541810-6

- R. Buckminster Fuller on Education (1979) ISBN 0-87023-276-2

- Synergetics 2: Further Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking (1979) in collaboration with E.J. Applewhite

- Buckminster Fuller – Autobiographical Monologue/Scenario (1980) page 54, R. Buckminster Fuller, documented and edited by Robert Snyder, St. Martin’s Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-10678-5

- Buckminster Fuller Sketchbook (1981)

- Critical Path (1981) ISBN 0-312-17488-8

- Grunch of Giants (1983) ISBN 0-312-35193-3

- Inventions: The Patented Works of R. Buckminster Fuller (1983) ISBN 0-312-43477-4

- Humans in Universe (1983) coauthor Anwar Dil, ISBN 0-89925-001-7

- Cosmography: A Posthumous Scenario for the Future of Humanity (1992) coauthor Kiyoshi Kuromiya, ISBN 0-02-541850-5

See alsoEdit

- Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station

- The Buckminster Fuller Challenge

- Bucky Ball

- Cloud Nine (tensegrity sphere)

- Design science revolution

- Drop City

- Emissions Reduction Currency System

- Kārlis Johansons, tensegrity innovator

- Kenneth Snelson, tensegrity sculptor

- Noosphere

- Old Man River’s City project

- Space frame

- Spome

- Whole Earth Catalog

- Post-scarcity economy

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. (2007). «Fuller, R. Buckminster». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on October 21, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ Serebriakoff, Victor (1986). Mensa: The Society for the Highly Intelligent. Stein and Day. pp. 299, 304. ISBN 978-0-8128-3091-0.

- ^ Staff (2010). «The History of Mensa: Chapter 1: The Early Years (1945-1953)». Mensa Switzerland. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ «Partial list of Fuller U.S. patents». Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ «Catalogue of Members: Harvard members elected from 1966-1981» (PDF). Harvard College Phi Beta Kappa. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Sieden, L. Steven (2011). «Biography of R. Buckminster Fuller — Section 4: 1947–1976». BuckyFullerNow.com. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ «Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter F» (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ «Website of St. Louis Literary Award». Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ Saint Louis University Library Associates. «Recipients of the Saint Louis Literary Award». Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ «Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement». www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Sieden, Steven (2000). Buckminster Fuller’s Universe: His Life and Work. ISBN 978-0738203799.

- ^ Provenzo, Eugene F. (2009). «Friedrich Froebel’s Gifts: Connecting the Spiritual and Aesthetic to the Real World of Play and Learning». American Journal of Play. 2 (1): 85–99. ISSN 1938-0399 – via ERIC.

- ^ a b c Pawley, Martin (1991). Buckminster Fuller. New York: Taplinger. ISBN 978-0-8008-1116-7.

- ^ Sieden, Lloyd Steven (2000). Buckminster Fuller’s Universe: His Life and Work. New York: Perseus Books Group. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-7382-0379-9.

However, in 1927 his own financial difficulties forced Mr. Hewlett to sell his stock in the company. Within weeks Stockade Building Systems became a subsidiary of Celotex Corporation, whose primary motivation was akin to that of other conventional companies: making a profit. Celotex management took one look at Stockade’s financial records and called for a complete overhaul of the company. The first casualty of the transition was Stockade’s controversial president [Buckminster Fuller, who was fired].

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster, Your Private Sky, p.27

- ^ a b c d Sieden, Lloyd Steven (1989). Buckminster Fuller’s Universe: His Life and Work. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7382-0379-9.

- ^ James Sterngold (June 15, 2008). «The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller». The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ Sieden, Lloyd Steven (1989). Buckminster Fuller’s Universe: His Life and Work. Basic Books. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7382-0379-9.

during 1927, Bucky found himself unemployed with a new daughter to support as winter was approaching. With no steady income the Fuller family was living beyond its means and falling further and further into debt. Searching for solace and escape, Bucky continued drinking and carousing. He also tended to wander aimlessly through the Chicago streets pondering his situation. It was during one such walk that he ventured down to the shore of Lake Michigan on a particularly cold autumn evening and seriously contemplated swimming out until he was exhausted and ending his life.

- ^ Sieden, Lloyd Steven (1989). Buckminster Fuller’s Universe: His Life and Work. Basic Books. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-7382-0379-9.

- ^ «Design – A Three-Wheel Dream That Died at Takeoff – Buckminster Fuller and the Dymaxion Car». The New York Times. June 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c Haber, John. «Before Buckyballs: Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi». Haber’s Arts Reviews.

See also: Glueck, Grace (May 19, 2006). «The Architect and the Sculptor: A Friendship of Ideas». The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2010. - ^ a b Lloyd Steven Sieden. Buckminster Fuller’s Universe: His Life and Work (pp. 74, 119–142). New York: Perseus Books Group, 2000. ISBN 0-7382-0379-3. p. 74: «Although O’Neill soon became well known as a major American playwright, it was Romany Marie who would significantly influence Bucky, becoming his close friend and confidante during the most difficult years of his life.»

- ^ a b Haskell, John. «Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi». Kraine Gallery Bar Lit, Fall 2007. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Schulman, Robert (2006). Romany Marie: The Queen of Greenwich Village. Louisville: Butler Books. pp. 85–86, 109–110. ISBN 978-1-884532-74-0.

- ^ «Interview with Isamu Noguchi conducted by Paul Cummings at Noguchi’s studio in Long Island City, Queens». Smithsonian Archives of American Art. November 7, 1973.

- ^ Gorman, Michael John (March 12, 2002). «Passenger Files: Isamu Noguchi, 1904–1988». Towards a cultural history of Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Car. Stanford Humanities Lab. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Includes several images.

- ^ «IDEAS + INVENTIONS: Buckminster Fuller and Black Mountain College, July 15 – November 26, 2005». Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center. 2005. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009.

- ^ Segaloff, Nat (2011). Arthur Penn: American director. Lexington, Ky: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0813129761. Available as a .pdf at https://epdf.pub/arthur-penn-american-director-screen-classics.html

- ^ Marks, Robert W.; Fuller, R. Buckminster (1973). The Dymaxion world of Buckminster Fuller. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-385-01804-3.

- ^ Jerry Coyne and Steve Jones (1995). «1994 Sewall Wright Award: Richard C. Lewontin». The American Naturalist. University of Chicago Press. 146 (1): front matter. JSTOR 2463033.

- ^ a b «Shoji Sadao». World Resource Simulation Center. 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Neely-Streit, Gabriel. «Fifty years of Fuller: SIU Carbondale celebrates iconic architect, futurist». The Southern.

- ^ a b Richard Buckminster Fuller Basic Biography. Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller.

- ^ «The Center for Spirituality & Sustainability». Siue.edu. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Norman Foster — Royal Gold Medal Presentation YouTube, March 26, 2015.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (1983). Inventions: The Patented Works of R. Buckminster Fuller. St. Martin’s Press. p. vii.

- ^ «Arthur Buckminster Fuller». Archived from the original on October 19, 2006.

- ^ «Buckminster Fuller: Designer of a New World, 1895-1983». Harvard Square Library. 2016. Archived from the original on August 6, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Brand, Stewart (1999). The Clock of the Long Now. New York: Basic. ISBN 978-0-465-04512-9.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (1969). Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2461-3.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster; Applewhite, E. J. (1975). Synergetics. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-541870-7.

- ^ François de Chadenèdes (November 18, 1920 — October 24, 1999) — His name in full was Jean Auguste François de Bournai Barthelemy de Chadenèdes. A petroleum geologist and priest, he was born in Flushing, New York. After graduating from Harvard College in 1943, he received an M.S. degree from Harvard University in 1947, and a Ph.D. degree from Stanford University in 1951. He worked in the petroleum industry for the next thirty years, retiring in 1981. He was a member of the Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists. As a geologist he was active in California, Colorado, Mexico, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming, and he worked with other geologists in Bali, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Moscow. He is credited with helping discover oil in the Moxa Arch area of Wyoming, and in the Overthrust Belt of western Wyoming and Utah. He served as an advisor to President Richard Nixon’s Environmental Quality Council (renamed the Cabinet Committee on the Environment), and, starting in 1975, he was a consultant to R. Buckminster Fuller on world energy. He contributed articles to many journals and books. In 1991 he was ordained a priest in the Episcopal Church, and he served as assistant and associate rector at Saint John’s Episcopal Church in Boulder, Colorado. He was a resident of Boulder for many years.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (1981). Critical Path. New York: St. Martin’s Press. xxxiv–xxxv. ISBN 978-0-312-17488-0.

- ^ Ament, Phil. «Inventor R. Buckminster Fuller». Ideafinder.com. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ «Buckminster Fuller World Game Synergy Anticapatory». YouTube. January 27, 2007. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ «The Debates». The Economist.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (1981). «Introduction». Critical Path (1st ed.). New York, N.Y.: St.Martin’s Press. xxv. ISBN 978-0-312-17488-0.

«It no longer has to be you or me. Selfishness is unnecessary and hence-forth unrationalizable as mandated by survival. War is obsolete.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (2008). Snyder, Jaime (ed.). Utopia or oblivion: the prospects for humanity. Baden, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers. ISBN 978-3-03778-127-2.

- ^ «Notable Individuals Influenced by General Semantics». The Institute of General Semantics. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Drake, Harold L. «The General Semantics and Science Fiction of Robert Heinlein and A. E. Van Vogt» (PDF). General Semantics Bulletin 41. Institute of General Semantics. p. 144. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

For his dissertation showing some relationships between formulations of Alfred Korzybski and Buckminster Fuller, plus documenting meetings and associations of the two gentlemen, he was given the 1973 Irving J. Lee Award in General Semantics offered by the International Society for General Semantics.

- ^ Edmondson, Amy, «A Fuller Explanation», Birkhauser, Boston, 1987, p19 tetrahedra, p110 octet truss

- ^ «Geodesic Domes and Charts of the Heavens». Telacommunications.com. June 19, 1973. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ «The R. Buckminster Fuller FAQ: Geodesic Domes». Cjfearnley.com. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c Lloyd Steven Sieden (August 11, 2000). Buckminster Fuller’s Universe. Basic Books. ISBN 9780738203799.

- ^ «R. (Richard) Buckminster Fuller 1895-1983». Coachbuilt.com.

- ^ US 2101057

- ^ Frank Magill (1999). The 20th Century A-GI: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 7. Routledge. p. 1266. ISBN 978-1136593345.

- ^ Phil Patton (June 2, 2008). «A 3-Wheel Dream That Died at Takeoff». The New York Times.

- ^ Sieden, Lloyd Steven (2000). Buckminster Fuller’s Universe. Basic Books. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7382-0379-9.

- ^ McHale, John (1962). R. Buckminster Fuller. Prentice-Hall. p. 17.

- ^ Marks, Robert (1973). The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller. Anchor Press / Doubleday. p. 104.

- ^ Art Kleiner (April 2008). The Age of Heretics. Jossey Bass, Warren Bennis Signature Series. ISBN 9780470443415.

In 1934, Fuller had interested auto magnate Walter Chrysler in financing his Dymaxion car, a durable, three-wheeled, aerodynamic land vehicle modeled after an airplane fuselage. Fuller had built three models that drew enthusiastic crowds wherever. Like all Fuller’s other projects (he was responsible for refining and developing the geodesic dome, the first practical dome structure) it was inexpensive, durable and energy efficient; Fuller worked diligently to cut back the amount of material and energy used by any product he designed. «You’ve produced exactly the car I’ve always wanted to produce,» the mechanically apt Chrysler told him. Then Chrysler noted ruefully, Fuller had taken one-third the time and one fourth the money Chrysler’s corporation usually spent producing prototypes — prototypes Chrysler himself usually hated in the end. For a few months, it had seemed Chrysler would go ahead and introduce Fuller’s car. But the banks that financed Chrysler’s wholesale distributors vetoed the move by threatening to call in their loans. The bankers were afraid (or so Fuller said years later) that an advanced new design would diminish the value of the unsold motor vehicles in dealers’ showrooms. For every new car sold, five used cars had to be sold to finance the distribution and production chain, and those cars would not sell if Fuller’s invention made them obsolete.

- ^ Marks, Robert (1973). The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller. Anchor Press / Doubleday. p. 29.

- ^ a b Nevala-Lee, Alec (August 2, 2022). «The Dramatic Failure of Buckminster Fuller’s «Car of the Future»«. Slate Magazine. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ «Passenger Files: Francis T. Turner, Colonel William Francis Forbes-Sempill and Charles Dollfuss». Stanford University Archives. Archived from the original on August 21, 2012.

- ^ Davey G. Johnson (March 18, 2015). «Maximum Dynamism! Jeff Lane’s Fuller Dymaxion Replica Captures Insane Cool of the Originals». Car and Driver.

- ^ R. Buckminster Fuller (1983). Inventions: The Patented Works of R. Buckminster Fuller. St. Martin’s Press.

- ^ «About Fuller, Session 9, Part 15». Bucky Fuller Institute.

- ^ Allison C. Meier. «Dymaxion Car at the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada. The only surviving prototype». AtlasObscura. Retrieved September 27, 2020.