Japan, island nation in East Asia, located in the North Pacific Ocean off the coast of the Asian continent. Japan comprises the four main islands of Honshû, Hokkaidô, Kyûshû, and Shikoku, in addition to numerous smaller islands. The Japanese call their country Nihon or Nippon, which means «origin of the sun.» The name arose from Japan’s position east of the great Chinese empires that held sway over Asia throughout most of its history. Japan is sometimes referred to in English as the «land of the rising sun.» Tokyo is the country’s capital and largest city.

Mountains dominate Japan’s landscape, covering 75 to 80 percent of the country. Historically, the mountains were barriers to transportation, hindering national integration and limiting the economic development of isolated areas. However, with the development of tunnels, bridges, and air transportation in the modern era, the mountains are no longer formidable barriers. The Japanese have long celebrated the beauty of their mountains in art and literature, and today many mountain areas are preserved in national parks.

Most of Japan’s people live on plains and lowlands found mainly along the lower courses of the country’s major rivers, on the lowest slopes of mountain ranges, and along the sea coast. This concentration of people makes Japan one of the world’s most crowded countries. Densities are especially high in the urban corridor between Tokyo and Kôbe, where 45 percent of the country’s population is packed into only 17 percent of its land area. An ethnically and culturally homogeneous nation, Japan has only a few small minority groups and just one major language–Japanese. The dominant religions are Buddhism and Shinto (a religion that originated in Japan).

Japan is a major economic power, and average income levels and standards of living are among the highest in the world. The country’s successful economy is based on the export of high-quality consumer goods developed with the latest technologies. Among the products Japan is known for are automobiles, cameras, and electronic goods such as computers, televisions, and sound systems.

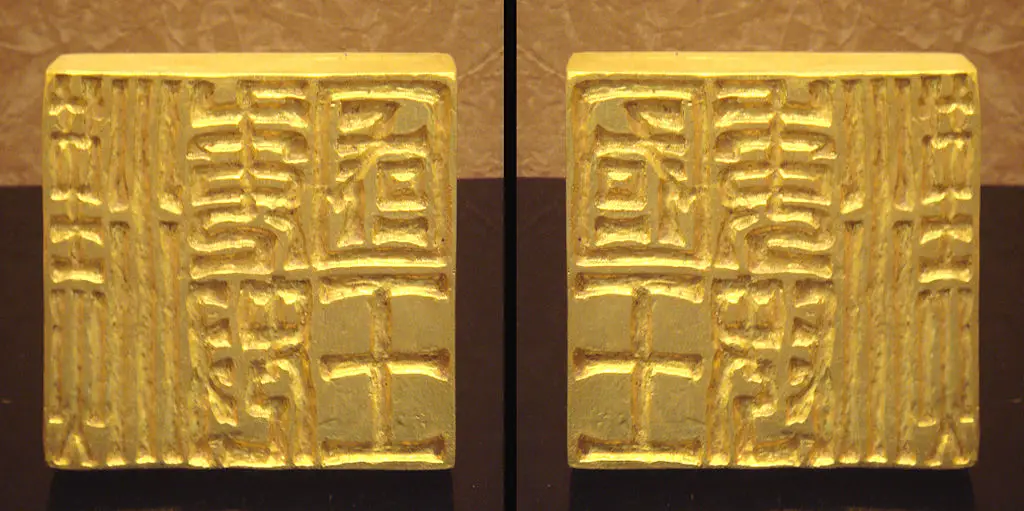

An emperor has ruled in Japan since about the 7th century. Military rulers, known as shoguns, arose in the 12th century, sharing power with the emperors for more than 600 years. Beginning in the 17th century, a powerful military government closed the country’s borders to almost all foreigners. Japan entered the 19th century with a prosperous economy and a strong tradition of centralized rule, but it was isolated from the rest of the world and far behind Western nations in technology and military power.

When Western nations, eager to trade with Japan, forced the country to open its borders in the mid-19th century, Japan’s shogun was ousted in a coup that restored the emperor to power. Under the rule of the Meiji emperor (1868-1912), Japan began a crash program of modernization and industrialization, as well as colonial expansion into Korea, China, and other parts of Asia. By the early 20th century, Japan had won a place among the world’s great powers.

Japan fought on the side of the Axis powers in World War II (1939-1945). By the time the war ended with Japan’s defeat, most of the country’s industrial facilities, transportation networks, and urban infrastructure had been destroyed. Japan also lost its colonial holdings as a result of the war. From 1945 to 1952 the United States and its allies occupied Japan militarily and administered its government. Under a revised constitution, the emperor assumed a primarily symbolic role as the head of state in Japan’s constitutional monarchy. During the postwar period, Japan rapidly rebuilt its economy and society. By the mid-1970s the country had established a lucrative trade with the United States and many other nations, and was well on its way to its present status as a top-ranking global economic power.

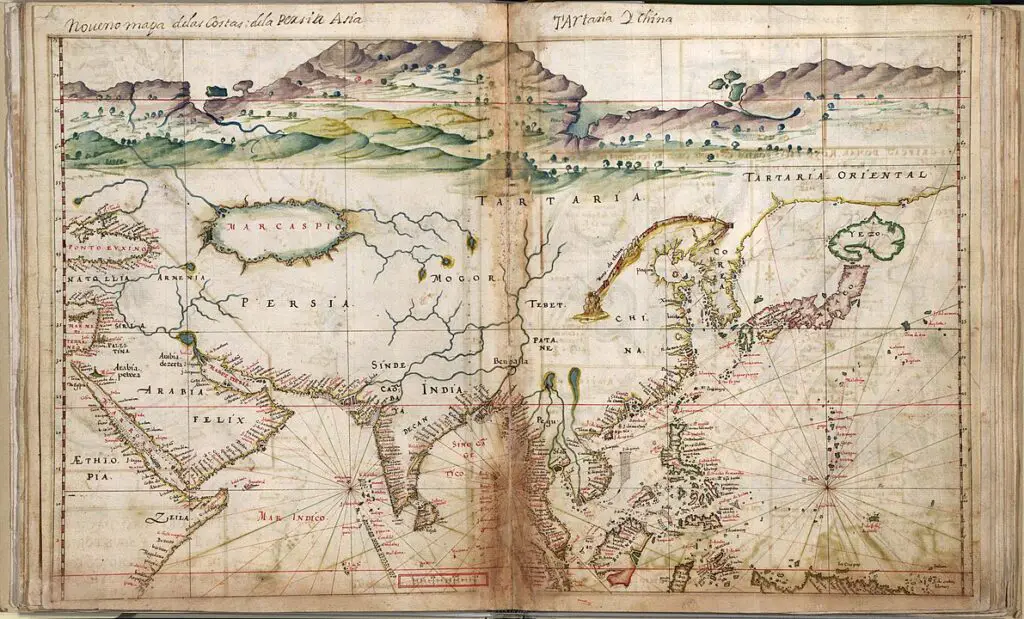

The portion of the Asian mainland closest to Japan is the Korea Peninsula, which is 200 km (100 mi) away at its nearest point (in South Korea). Japan does not share a land border with any other country, but nearby are far eastern Russia, located to the northwest across the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan (East Sea); South Korea and North Korea, to the west across the Korea Strait and the Sea of Japan; and China and Taiwan, to the southwest across the East China Sea.

The introduction to this article was contributed by Roman Cybriwsky.

According to legend, the Japanese islands were created by gods, who dipped a jeweled spear into a muddy sea and formed solid earth from its droplets. Scientists now know that the islands are the projecting summits of a huge chain of undersea mountains. Colliding tectonic plates lifted and warped the earth’s crust, causing volcanic eruptions and intrusions of granite that pushed the mountains above the surface of the sea. The forces that created the islands are still at work. Earthquakes occur regularly in Japan, and about 40 of the country’s 188 volcanoes are active, a number representing 10 percent of the world’s active volcanoes.

Japan’s total area is 377,837 sq km (145,884 sq mi). Honshû is the largest of the Japanese islands, followed by Hokkaidô, Kyûshû, and Shikoku. Together the four main islands make up about 95 percent of Japan’s territory. More than 3,000 smaller islands constitute the remaining 5 percent. At their greatest length from the northeast to southwest, the main islands stretch about 1,900 km (about 1,200 mi) and span 1,500 km (900 mi) from east to west.

Japan’s four main islands are separated by narrow straits: Tsugaru Strait lies between Hokkaidô and Honshû, and the narrow Kammon Strait lies between Honshû and Kyûshû. The Inland Sea (Seto Naikai), an arm of the Pacific Ocean, lies between Honshû, Shikoku, and Kyûshû. The sea holds more than 1,000 islands and has two principal access channels, Kii Channel on the east and Bungo Strait on the west.

Japan also includes more distant island groups. The Ryukyu Islands (Nansei Shotô), made up of the Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima island chains, extend southwest from Kyûshû for 1,200 km (700 mi). The Izu Islands, the Bonin Islands, (Ogasawara Shotô), and the Volcano Islands (Kazan Rettô) extend south from Tokyo for 1,100 km (700 mi).

Japan also claims ownership of several islands north of Hokkaidô. These include the two southernmost Kuril Islands, Ostrov Iturup (Etorofu-jima) and Ostrov Kunashir (Kunashiri-jima), as well as Shikotan and the Habomai island group. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) took control of these islands from Japan after World War II ended in 1945. Since the USSR dissolved in 1991, Russia has administered the disputed islands.

A spine of mountain ranges divides the Japanese archipelago into two halves, the «front» side facing the Pacific Ocean, and the «back» side facing the Sea of Japan. High, steep mountains scored by deep valleys and gorges mark the Pacific side, while lower mountains and plateaus distinguish the Sea of Japan side. The country is traditionally divided into eight major regions: Hokkaidô, Tôhoku, Kantô, Chûbu, Kinki, Chûgoku, Shikoku, and Kyûshû and the Ryukyu Islands.

Hokkaidô is Japan’s large northern island. Most of the island is mountainous and heavily forested. Hokkaidô has a number of volcanoes, including Asahi Dake, which stands 2,290 m (7,513 ft) high in the Ishikari Mountains and is the island’s highest peak. Hokkaidô also holds one of Japan’s largest alluvial plains, the Ishikari Plain. The island’s fertile soils support agriculture and provide the vast majority of Japan’s pasturelands. In addition, Hokkaidô contains coal deposits, and the cold currents off its shores supply cold-water fish.

Winters are long and harsh, so most of Hokkaidô is lightly settled, housing about 5 percent of Japan’s population on approximately 20 percent of its land area. However, its snowy winters and unspoiled natural beauty attract many skiers and tourists. Hokkaidô is thought of as Japan’s northern frontier because Japanese people settled it only after the middle of the 19th century. Most of the remaining Ainu people, who populated Hokkaidô before the arrival of the Japanese, live on the island. The island of Hokkaidô forms a single prefecture. Its capital, Sapporo, is an important commercial and manufacturing center.

The northern part of Honshû island is the region known as Tôhoku, meaning «the northeast.» Like Hokkaidô, Tôhoku is mountainous, forested, and generally lightly settled, although its population density is about twice that of its northern neighbor. Tôhoku’s most important flatland is the Sendai Plain, located on the Pacific Ocean side of the region. Despite a short growing season, Tôhoku is an important agricultural area. During the cold winters, many of Tôhoku’s farmers move to Tokyo and other cities for seasonal work in construction and factories. Many young people move away too, often permanently, to enter the labor market and build careers in other regions. Consequently, Tôhoku has been one of Japan’s slowest growing regions. Tôhoku includes the prefectures of Aomori, Iwate, Akita, Yamagata, Miyagi, and Fukushima. Its principal city is Sendai.

South of Tôhoku on Honshû island is the Kantô region, the political, cultural, and economic heart of Japan. It centers on Japan’s capital city, Tokyo, in east central Honshû. Kantô’s main natural feature is the Kantô Plain. Japan’s largest flatland, the plain covers 13,000 sq km (5,000 sq mi), or about 40 percent of the Kantô region. Hills and mountains surround the plain on the east, north, and west sides, while the south side opens to the Pacific Ocean. Covering most of the southern part of the plain is the Tokyo metropolitan area, which contains many small cities and satellite towns. Major nearby cities–Yokohama, Chiba, and Kawasaki–merge with Tokyo, creating one large urban-industrial zone. The population of Kantô is the largest of any of Japan’s regions. Most of the farms that once covered the Kantô Plain have been replaced by residential, commercial, and industrial construction. The prefectures of Kanagawa, Saitama, Gumma, Tochigi, Ibaraki, Chiba, and the Tokyo Metropolis make up the Kantô region.

Chûbu, meaning «central region,» encompasses central Honshû west of Kantô. This region contains some of Japan’s longest rivers, its highest mountains, and numerous volcanoes. The Japanese Alps run through the center of Chûbu, dividing the region into three districts. The central district, known as Tôsan, contains the three parallel mountain ranges that make up the alps: the Hida Mountains (Northern Alps), the Kiso Mountains (Central Alps), and the Akaishi Mountains (Southern Alps). At least ten peaks in the Alps exceed 3,000 m (10,000 ft). The highest peak is Kita Dake, which stands at 3,192 m (10,474 ft) in the northern Akaishi range. Most inhabitants of the district live in elevated basins and narrow valleys scattered among the mountains. Silk traditionally has been produced in Tôsan’s valleys, although that industry has declined in recent decades.

West of the alps lies the Hokuriku district on the Sea of Japan. It receives heavy winter snowfalls, and its rapidly flowing rivers provide bountiful hydroelectric power. Extensive rice fields cover Hokuriku’s plains, while its main cities are important manufacturing centers.

Tôkai, the district east of the alps on the Pacific coast, is sunnier and warmer. Most of Japan’s tea is produced there. Chûbu’s biggest city, Nagoya, is located on the Nôbi Plain, a densely populated agricultural and industrial region. Also located in Tôkai is Japan’s highest mountain, Fuji, a remarkably symmetrical volcanic cone that rises to 3,776 m (12,387 ft). Referred to in Japan as Fuji-san, the mountain is beloved by many Japanese and appears often in art and as a symbol of the country. Fuji last erupted in 1707. During the July and August climbing season, thousands of climbers ascend the mountain each day. Many spend the night in order to see the sun rise the next morning from the horizon on the Pacific Ocean.

Chûbu encompasses the prefectures of Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, Fukui, Yamanashi, Nagano, Gifu, Shizuoka, and Aichi.

The Kinki region lies west of Chûbu in west central Honshû. Kinki spans Honshû from the Sea of Japan to the Inland Sea, and occupies the Kii Peninsula, a large thumb of land with heavily indented coasts jutting south into the Pacific Ocean. Coastal plains edge Kinki’s mountainous interior. The largest of these is the Ôsaka Plain, which faces Ôsaka Bay on the Inland Sea and contains Ôsaka, the region’s largest city. Japan’s second-most populous region, Kinki holds the Hanshin Industrial Zone, noted for heavy industry and chemical manufacturing. The region is also historically and culturally important as the location of the former capital cities of Nara and Kyôto. The prefectures of Ôsaka, Hyôgo, Kyôto, Shiga, Mie, Wakayama, and Nara make up the Kinki region.

Chûgoku, which means «middle country,» lies between the Inland Sea and the Sea of Japan at the western end of Honshû. The Chûgoku Mountains run from east to west through the center of the region. The zone south of the mountains along the Inland Sea, called San’yô or «the sunny side,» has a mild climate and a relatively high population density. Its warm coastal plains support rice fields, citrus orchards, and vineyards. Also located on these plains are several major industrial and port cities, including the region’s principle city, Hiroshima. The Sea of Japan coast, called San’in or «the shady side,» is colder, lacks natural harbors, and is less urbanized. The Sea of Japan traditionally has been important for fishing and aquaculture (water animal and plant cultivation), but these activities have declined due to industrial pollution. The Chûgoku region encompasses the prefectures of Hiroshima, Okayama, Shimane, Tottori, and Yamaguchi.

The Shikoku region consists of Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, and many small surrounding islands. Relatively low but steep mountains cover most of Shikoku island. The tallest peak on the island (and in the region) is Mount Ishizuchi at 1,982 km (6,503 ft). Shikoku’s mountainous terrain has limited settlement primarily to coastal plains on the northern shore along the Inland Sea. There, the towns of Matsuyama and Takamatsu serve as important regional commercial and industrial centers. The Kôchi Plain, a zone of mild winters in the southern part of Shikoku island, supports citrus fruits and various vegetables. The opening of three separate bridge systems between Shikoku and Honshû since 1988 has reduced the region’s isolation. Shikoku includes the prefectures of Kagawa, Tokushima, Ehime, and Kôchi.

The region of Kyûshû and the Ryukyu Islands consists of Kyûshû, the third largest of Japan’s four major islands; many small surrounding islands; and the Ryukyu Islands, located south of Kyûshû. Kyûshû’s interior is mountainous with numerous volcanoes, some of which are active. A notable example is Mount Aso in central Kyûshû. Its huge caldera (round or oval-shaped low-lying area that forms when a volcano collapses) measures 80 km (50 mi) in circumference. The volcanic cone on Sakurajima, a volcanic island off Kyûshû, has erupted more than 5,000 times since 1955. The tallest mountain on Kyûshû is Kujû, measuring 1,788 m (5,866 ft). Kyûshû’s volcanic mountain scenery and the resorts built around its thermal hot springs attract many tourists.

Coal deposits in northern Kyûshû have made the area an important industrial center, specializing in the production of iron, steel, chemicals, and machinery. In addition to rice and vegetables, Kyûshû’s farmers grow subtropical fruits and raise cattle. The island is connected to the mainland by a bridge and several tunnels, including one for Japan’s high-speed train, the Shinkansen. Kyûshû’s largest city is Fukuoka.

The Ryûkyû chain’s larger islands are volcanic, while the smaller ones are coral formations. Farmers grow sugarcane and pineapples in the islands’ frost-free climate. The bathing beaches of Okinawa, the largest and most populated of the Ryukyu Islands, make it an especially popular tourist destination.

The prefectures of Fukuoka, Nagasaki, Ôita, Kumamoto, Miyazaki, Saga, Kagoshima, and Okinawa make up the Kyûshû and Ryukyu Islands region.

Japan lies in a zone of extreme geological instability, where four tectonic plates—the Pacific plate, the Eurasian plate, the North American plate, and the Philippine plate—come together. As the plates push against one another, they cause violent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. As many as 1,500 earthquakes occur in Japan each year. While most of these are minor and cause no damage, typically several of them rattle buildings enough to cause dishes to break and goods to topple from shelves. Occasionally earthquakes are severe enough to cause widespread property damage and loss of life. Japan’s largest earthquakes in the 20th century have been the Great Kantô Earthquake of 1923, in which more than 140,000 people died in the Tokyo-Yokohama metropolis, and the 1995 earthquake in Kôbe that killed more than 6,400 people. The Kôbe quake also caused massive damage to buildings, highways, and other infrastructure in Kôbe and its vicinity. An earthquake centered offshore may cause a deadly tidal wave called a tsunami. Earthquakes pose such danger to the country that Japan has become a world leader in earthquake prediction, earthquake-proof construction techniques, and disaster preparedness by both civil defense forces and the general public.

Japan has a long and irregular coastline totaling some 29,750 km (18,490 mi). The coastlines of Hokkaidô and western and northern Honshû are relatively straight. The most prominent features of Hokkaidô’s coastline are the Oshima Peninsula at the south end of the island and the Uchiura and Ishikari bays, which flank the peninsula on opposite coasts. The western coast of Honshû on the almost tideless Sea of Japan possesses Japan’s largest sandy beaches and its tallest dunes. The only conspicuous indentations in this coastline are Wakasa and Toyama bays and one major peninsula, the Noto Peninsula. The eastern coast of Honshû north of Tokyo has few navigable inlets.

By contrast, the coastlines of eastern Honshû south of Tokyo and of Kyûshû contain deep indentations resulting from erosion by tides and severe coastal storms. Japan’s most important bays are all on the irregular Pacific coast of central and southern Honshû: Tokyo Bay at Tokyo and Yokohama, Ise Bay near Nagoya, and Ôsaka Bay at the Kôbe-Ôsaka metropolis. All of these bays have major harbors. The eastern coast of central and southern Honshû also contains several of Japan’s most prominent peninsulas: the Chiba, Izu, and Kii peninsulas. Kyûshû’s coastline is marked by the Satsuma and Nagasaki peninsulas and Kagoshima Bay.

The economic importance of Japan’s coastline is seen in its hundreds of towns and villages given to fishing, whaling, and aquaculture, as well as in its several major international ports and many huge industrial complexes. Most of Japan’s urban centers are located on or near the coast. In many urban-industrial areas, the coastline has been extended by reclamation projects to create new land for sprawling factories, oil storage tanks, expanded harbor facilities, airports, and other uses.

Most of Japan’s rivers are relatively short and swift flowing. Only a few are navigable beyond their lower courses. Japan’s longest river, the Shinano, arises in the mountains of central Honshû and flows for 367 km (228 mi) to empty into the Sea of Japan. Other major rivers are the Tone River in the northern Kantô Plain and the Ishikari River in Hokkaidô.

Rivers in Japan often have low water levels during dry seasons but may flood during rainy periods and after winter snows melt. Except in the highest mountains, the courses of almost all rivers have been altered by flood control measures such as artificial channels and levees. In addition, many rivers have multiple dams and chains of reservoirs to regulate water flow and to supply cities and farms downriver with water for industry, irrigation, and domestic use. The dams also generate electric power. Japan’s largest dam is the Kurobe Dam, standing 186 m (610 ft) high, on the Kurobe River in Toyama Prefecture.

Japan’s largest lake, Biwa, lies in central Honshû’s Shiga Prefecture. It measures 670 sq km (260 sq mi) and is 104 m (341 ft) deep at its deepest point. Biwa is a popular scenic attraction, an important source of freshwater fish, and a local transportation artery. Japan’s second-largest lake is Kasumiga-ura, located in the central Honshû prefecture of Ibaraki. It measures 168 sq km (65 sq mi) and is an important source of eel, carp, and other freshwater species. Lake Kussharo in Hokkaidô is an example of a caldera lake. It measures 80 sq km (31 sq mi) and has an island in its center formed by a volcano. The waters of this lake are acidic and barren of fish.

More than 17,000 species of flowering and nonflowering plants are found in Japan, and many are cultivated widely. Azaleas color the Japanese hills in April, and the tree peony, one of the most popular cultivated flowers, blossoms at the beginning of May. The lotus blooms in August, and in November the blooming of the chrysanthemum, the national flower of Japan, occasions one of the most celebrated of the numerous Japanese flower festivals. Various types of seaweed grow naturally or are cultivated in offshore waters, adding variety to the Japanese diet. The most common varieties of edible seaweed are laver (a purple form of red algae also known as nori), kelp (a large, leafy brown algae also called kombu), and wakame (a large brown algae).

Forests cover 67 percent of Japan’s land area. Forests are concentrated on mountain slopes, where trees are important in soil and water conservation. Tree types vary with latitude and elevation. In Hokkaidô, spruce, larch, and northern fir are most common, along with alder, poplar, and beech trees. Central Honshû’s more temperate climate supports beech, willows, and chestnuts. In Shikoku, Kyûshû, and the warmer parts of Honshû, subtropical trees such as camphors and banyans thrive. The southern areas also have thick stands of bamboo. Japanese cedars and cypresses are found throughout wide areas of the country and are prized for their wood. Cultivated tree species include fruit trees bearing peaches, plums, pears, oranges, and cherries; mulberry trees for silk production; and lacquer trees, from which the resins used to produce lacquer are derived. Potted miniaturized trees called bonsai are popular among hobbyist gardeners in Japan and are a highly evolved art form.

Japanese animal life includes at least 140 species of mammals; 450 species of birds; and a wide variety of reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Mammals include wild boar, deer, rabbits and hares, squirrels, and various species of bear. Foxes and badgers also are numerous and, according to traditional beliefs, possess supernatural powers. The only primate mammal in Japan is the Japanese macaque, a red-faced monkey found throughout Honshû. The most common birds are sparrows, house swallows, and thrushes. Water birds are common as well, including cranes, herons, swans, storks, cormorants, and ducks. The waters off Japan abound with fish and other marine life, particularly at around 36º N latitude, where the cold Oyashio and warm Kuroshio currents meet and create ideal conditions for larger species.

Japan has had to build its enormous industrial output and high standard of living on a comparatively small domestic resource base. Most conspicuously lacking are fossil fuel resources, particularly petroleum. Small domestic oil fields in northern Honshû and Hokkaidô supply less than 1 percent of the country’s demand. Domestic reserves of natural gas are similarly negligible. Coal deposits in Hokkaidô and Kyûshû are more abundant but are generally low grade, costly to mine, and inconveniently located with respect to major cities and industrial areas (the areas of highest demand). Japan does have abundant water and hydroelectric potential, however, and as a result the country has developed one of the world’s largest hydroelectric industries.

Japan is also short on metal and mineral resources. It was once a leading producer of copper, but its great mines at Ashio in central Honshû and Besshi on Shikoku have been depleted and are now closed. Reserves of iron, lead, zinc, bauxite, and other ores are negligible.

While the country is heavily forested, its demand for lumber, pulp, paper, and other wood products exceeds domestic production. Some forests in Hokkaidô and northern Honshû have been logged excessively, causing local environmental problems. Japan is blessed with bountiful coastal waters that provide the nation with fish and other marine foods. However, demand is so large that local resources must be supplemented with fish caught by Japanese vessels in distant seas, as well as with imports. Although arable land is limited, agricultural resources are significant. Japan’s crop yields per land area sown are among the highest in the world, and the country produces more than 60 percent of its food.

Japan’s climate is rainy and humid, and marked in most places by four distinct seasons. The country’s wide range of latitude causes pronounced differences in climate between the north and the south. Hokkaidô and other parts of northern Japan have long, harsh winters and relatively cool summers. Average temperatures in the northern city of Sapporo dip to –5° C (24° F) in January but reach only 20° C (68° F) in July. Central Japan has cold but short winters and hot, humid summers. In Tokyo in central Honshû, temperatures average 3° C (38° F) in January and 25° C (77° F) in July. Kyûshû is subtropical, with short, mild winters and hot, humid summers. Average temperatures in the southern city of Kagoshima are 7° C (45° F) in January and 26° C (79° F) in July. Farther south, the Ryukyu Islands are warmer still, with frost-free winters.

The climate of Japan is influenced by the country’s location on the edge of the Pacific Ocean and by its proximity to the Asian continent. The mountain ranges running through the center of the islands also influence local weather conditions. The Sea of Japan side of the country is extremely snowy in winter. Cold air masses originating over the Asian continent absorb moisture as they pass over the Sea of Japan, then rise as they encounter Japan’s mountain barriers, cooling further and dropping their moisture in the form of snow. The heaviest snows are in Nagano Prefecture, where annual accumulations of 8 to 10 m (26 to 30 ft) are common. By contrast, Pacific Japan lies in a snow shadow on the sheltered side of the mountains and experiences fairly dry winters with clear skies.

From June to September this pattern reverses. Monsoon winds from the Pacific tropics bring warm, moist air and heavy precipitation to Japan’s Pacific coast. A month-long rainy season called baiu begins in southern Japan in early June, traveling north as the month progresses. Baiu is followed by hot, humid weather. In late August and September, the shûrin rains come to much of the country, often as torrential downpours that trigger landslides and floods. During this period, violent storms called typhoons come ashore in Japan, most often in Kyûshû and Shikoku. Japan’s distant tropical islands also suffer typhoon damage. Meanwhile, throughout the summer the Sea of Japan coast is protected from the Pacific influences by the mountains and is relatively dry. Northern Honshû and Hokkaidô receive relatively little summer precipitation. Average annual precipitation in Sapporo is 1,130 mm (45 in), while in Tokyo it is 1,410 mm (55 in) and in Kagoshima it is 2,240 mm (88 in).

Autumn and spring are generally pleasant in all parts of Japan. The season when cherry blossoms open (typically late March to early May, depending on latitude and elevation) is particularly festive.

Japan experienced severe environmental pollution during its push to industrialize in the late 19th century and again during the rush to rebuild the economy after World War II. Some of the worst pollution incidents caused great human suffering. One of the first episodes began in the late 19th century, when copper mining operations released effluents that contaminated rivers and rice fields in the mountains of central Honshû, sickening much of the local population. Crusading legislator Tanaka Shôzô led citizen protests that represented an important first step in the creation of a Japanese environmental movement and also provided an early example of grassroots political organization. Nevertheless, more environmental disasters followed. In the early 20th century cadmium poisoning caused an outbreak of a painful bone disease, called itai-itai, in Toyama Prefecture. From the 1950s to the 1970s, mercury contamination in fishing waters caused Minamata disease, an affliction of the central nervous system named after the town in Kyûshû where thousands became ill and hundreds died. Smog, arsenic poisoning, and polychlorobiphenyl (PCB) poisoning produced by industry in the 1970s caused other health problems.

Since that time, Japan has enacted some of the world’s strictest legislation for environmental protection and has become a world leader in environmental awareness and cleanup. The government took important steps to improve environmental quality in the late 1960s and early 1970s in response to pressure by citizens’ groups. It passed successive laws to combat pollution and compensate victims of pollution. In 1971 it established the Environmental Agency to monitor and regulate pollution.

Nevertheless, significant problems remain. Continued pollution of bays and other coastal waters have caused losses to the fishing and aquaculture industries. Emissions by power plants and heavy industry have resulted in acid rain (a type of air pollution) and increasing acidity of freshwater lakes. Despite improvements in recent years, smog continues to plague traffic-choked urban areas. Finally, despite successes in promoting recycling and reuse, the total amount of garbage produced per person has increased sharply since the mid-1980s, and waste disposal is a mounting problem in Japan’s urban areas.

The Land and Resources section of this article was contributed by Roman Cybriwsky.

Japan ranks as the world’s seventh most populous nation, with a population of 125,931,533) (1998 estimate). It is also one of the most crowded, with an average population density of 333 persons per sq km (863 per sq mi). The population is distributed unevenly within the country. Densities range from very low levels in the steep mountain areas of Hokkaidô and the interior of Honshû island to extraordinarily high levels in the urban areas on Japan’s larger plains. The most crowded area is central Tokyo, where overall population density is about 13,000 persons per sq km (about 33,000 per sq mi). About 78 percent of Japan’s people are concentrated in urban areas, making Japan one of the most heavily urbanized nations in the world.

Although Japan is one of the world’s most populous and crowded countries, it is also one of the slowest growing. At present, the annual population growth rate is 0.20 percent. At this rate the population will take 354 years to double. The slow rate of increase is due to low birthrates (10.3 births per 1,000 people in 1998) and a relatively low rate of foreign immigration. Birthrates are now less than one-third what they were in Japan before the 1950s, when it was common for couples to have three or more children. The average number of children per couple in Japan is now less than 1.5. The total population of the country is expected to begin declining soon because Japan’s net reproduction rate has been below 1.0 for a number of years (meaning that the Japanese population is not replacing itself). Projections call for population totals of about 120 million in 2025 and about 101 million in 2050. The prospect of such significant decline raises worries in Japan about whether the country will have a sufficient labor force to meet economic needs and enough people of working age to support the growing proportion of the population that is elderly.

The age structure of Japan’s population has changed tremendously in recent decades. The segment of the population between the ages of 0 and 14 declined from 35.4 percent in 1950 to 15.2 percent in 1998, while the number of people aged 65 or older increased from 4.9 percent to 16.0 percent. In 1995 Japan’s elderly outnumbered its youth for the first time in the country’s history. Life expectancy increased over the same period, largely due to improved health conditions, and is now 83 years for females and 77 years for males, in both cases the highest expected longevity in the world. The number of people in Japan aged 85 or over has increased from 134,000 in 1955 to an estimated 4.3 million in 1998.

Japan’s largest city is Tokyo, the national capital. In addition to being the center of government, Tokyo is Japan’s principal commercial center, home to most of the country’s largest corporations, banks, and other businesses. It is also a leading center of manufacturing, higher education, and communications. Japan’s second largest city is Yokohama, located near Tokyo in Kanagawa Prefecture. Originally a small fishing village, the settlement became a major port and international trade center after it was opened to foreign commerce in 1859. It grew quickly and continues to be Japan’s largest port, a busy commercial center, and along with Tokyo and neighboring Kawasaki, a hub of Japan’s preeminent Keihin Industrial Zone (an area of industrial concentration). The third largest city in the country is Ôsaka. Even in Japan’s feudal era, Ôsaka was an important commercial center and castle town, and it was known as «Japan’s kitchen» because of its role in warehousing rice for the nation. Today it is the leading financial center of western Japan and the principal city of the Hanshin Industrial Zone.

Other major cities are Nagoya, the focus of the Chûkyô Industrial Zone and a major port on Ise Bay; Sapporo, Hokkaidô’s capital and an important food-processing center; and Kôbe, a major port and shipbuilding center. Kyôto, Japan’s seventh-largest city, is especially famous as an ancient capital of Japan and the site of many historic temples, shrines, and traditional gardens. It is also known for manufacturing silk brocades and textiles.

Most of these major cities are crowded into a relatively small area of land along the Pacific coast of Honshû, between Tokyo and Kôbe. This heavily urbanized strip is known as the Tôkaidô Megalopolis, named for a historic highway that connected Tokyo with Kyôto. The cities are now interconnected by expressways and Japan’s high-speed Shinkansen railway.

The overwhelming majority of Japan’s population is ethnically Japanese. Closely related to other East Asians, the Japanese people are believed to have migrated to the islands of present-day Japan from the Asian continent and the South Pacific more than 2,000 years ago. The Ainu are Japan’s only indigenous ethnic group. Japan is also home to comparatively small groups of Koreans, Chinese, and residents from other countries. All told, the non-Japanese portion of the population totals no more than 2 percent, making Japan one of the most homogeneous countries in the world in terms of ethnic or national composition.

Although the origins of the Ainu are uncertain, traditional belief holds that they descended from the earliest settlers of Japan, who arrived long before the first Japanese. Their physical characteristics suggested to early anthropologists that they were Caucasoid (ultimately originating in southeastern Europe) or Australoid (originating in Australia and Southeast Asia). More recent scholarship suggests that they are related to the Tungusic, Altaic, and Uralic peoples of Siberia. The Ainu once inhabited a wider area of northern Japan but are now concentrated in a few settlements on Hokkaidô, the Kuril Islands, and Russia’s Sakhalin island. Speakers of the Ainu language number about 15,000. The Ainu have a distinct language and religious beliefs, and a rich material culture. Many engage in agriculture, fishing, and logging, or in tourism in their distinctive villages.

Koreans are the largest nonnative group in Japan, numbering 645,000. When the Japanese colonized Korea in the early 20th century, they forced many Koreans to move to Japan to work in Japanese mines and factories. Many Koreans living in Japan today are the children of these unwilling immigrants. They have permanent resident status in Japan and most rights of citizenship, but they face roadblocks to full citizenship and often suffer discrimination. Koreans make up more than 51 percent of all foreign residents in Japan. The next-largest group is the Chinese, some of whom were likewise forcibly relocated during Japan’s occupation of Taiwan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sizeable communities of Brazilians, Filipinos, and Americans also live in Japan. Since the 1980s workers from Asian countries such as China, the Philippines, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Iran have come to Japan on temporary visas to work in construction and industry doing so-called «3K» jobs (kitsui, kitanai, and kiken, or «difficult, dirty, and dangerous») that Japanese workers avoid. These foreign workers often live in inferior conditions and are generally shunned by many Japanese.

Japanese is the official language of Japan. The Japanese language is distinctive and of unknown origin. However, it has some relation to the Altaic languages of central Asia and to Korean, which may also be an Altaic language. Linguists also find similarities between Japanese and the Austronesian languages of the South Pacific.

Japanese has a number of regional dialects. Standard Japanese, the form heard most commonly on national television and radio, is traditionally the dialect of educated people in Tokyo but is now understood everywhere in Japan. Although standard Japanese has begun to replace some regional accents, many of these remain quite strong and distinctive. For example, dialects spoken in southern Japan—most notably on Kyûshû and Okinawa—are virtually incomprehensible to speakers of other dialects. Residents of western Japan around Ôsaka, Kyôto, and Kôbe also speak with distinctive accents.

Japanese speech is sensitive to social relationships. Several degrees of politeness and familiarity exist to distinguish between superiors, equals, and inferiors based on factors such as age, sex, and social status.

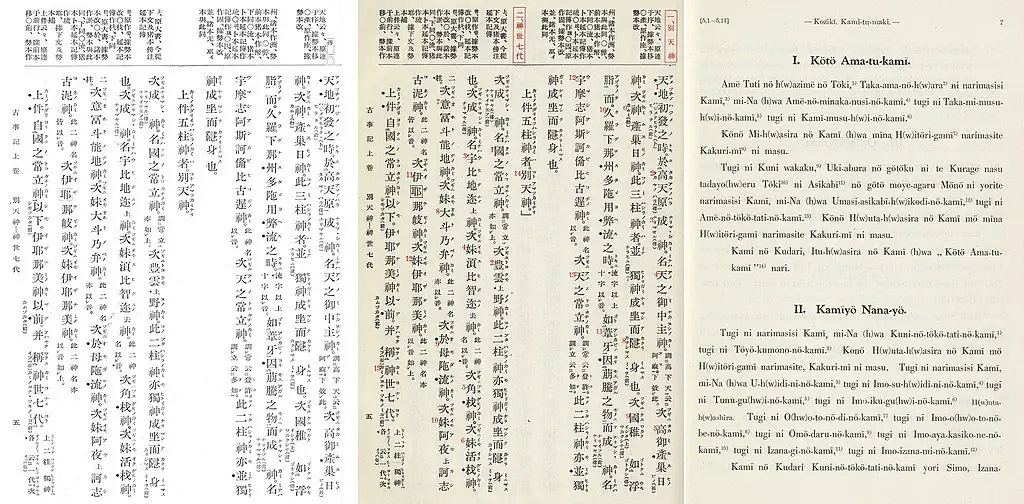

Japanese was solely a spoken language before the Chinese writing system was introduced to Japan in about the 5th century. By the 9th century, Japanese people had adapted Chinese writing to their own language and assimilated many Chinese words. Modern Japanese writing combines Chinese characters (kanji) with two syllabaries (alphabets in which each symbol represents a syllable), hiragana and katakana. Kanji are used to write native Japanese nouns and verbs, as well as the many Japanese words that originated in Chinese. Although there are tens of thousands of kanji, the government has identified about 2,000 for daily use. The hiragana syllabary is used for grammatical elements and word suffixes, while non-Chinese foreign words are written using katakana. Japanese includes many such loan words taken from Portuguese, Dutch, German, and increasingly, English. An example from English is kompûtâ, the Japanese word for computer. The Roman alphabet also is used commonly in advertisements and for emphasis and visual impact. It is not uncommon to see kanji, katakana, hiragana, and roman letters all used in the same sentence.

Japanese is usually written vertically and from right to left across a page. Thus, the first page of a Japanese book is what readers of English would normally think of as the last page. In modern times, Japan has adopted the Western style of writing horizontally and from left to right for some publications, such as textbooks. Written or printed Japanese has no spaces between words.

Ainu is Japan’s only other indigenous language. It is apparently unrelated to Japanese and is now nearly extinct. Korean and Chinese residents of Japan usually speak Japanese as their first language. Many Japanese students study foreign languages, most commonly English.

Japan is primarily a secular society in which religion is not a central factor in most people’s daily lives. Yet certain religious traditions and practices are vitally important and help define the society, and most Japanese people profess at least some religious adherence.

The dominant religions in Japan are Shinto and Buddhism. Shinto is native to Japan. Generally translated as «the Way of the Gods,» Shinto is a mixture of religious beliefs and practices, and its roots date back to prehistory. It was first mentioned in 720 in the Nihon shoki, Japan’s earliest historical chronicle. Unlike most major world religions, Shinto has no organized body of teachings, no recognized historical founder, and no moral code. Instead, it focuses on worship of nature, ancestors, and a pantheon of kami, sacred spirits or gods that personify aspects of the natural world. From 1868 to 1945, under the Japanese imperial government, Shinto was Japan’s state religion. After Japan’s defeat in World War II, the occupation government separated Shinto from state support.

Buddhism originated in India, arriving in Japan in the 6th century by way of China and Korea. In the centuries that followed, numerous Buddhist sects took root in Japan, among them Zen Buddhism. Zen was introduced from China in the 12th century and quickly became popular among the dominant warrior class under the rule of Japan’s first shogunate (military government), the Kamakura. Today the largest Buddhist sect in Japan is the Nichiren school.

Shinto and Buddhism have been intertwined in Japanese society for centuries, and about 85 percent of the population identify themselves as members of one or both of these religions. Indeed, most Japanese blend the two, preferring attendance at Shinto shrines for some events—such as New Year’s Day, wedding ceremonies, and the official start of adulthood at age 20—and Buddhist ceremonies for other events, most notably Obon (a midsummer celebration honoring ancestral spirits) and funerals. Confucianism and Daoism, which came to Japan from China by way of Korea, have also profoundly influenced Japanese religious life.

More than 20 million Japanese are members of various shinkô shûkyô, or «new religions.» The largest of these are Sôka Gakkai and Risshô Kôseikai, offshoots of Nichiren Buddhism, and Tenrikyô, an offshoot of Shinto. Most of the new religions were founded by charismatic leaders who have claimed profound spiritual or supernatural experiences and expect considerable devotion and sacrifices from members. Although it is very small in comparison to other religions, one of Japan’s new religions, Aum Shinrikyo, gained considerable notoriety when some of its members released nerve gas into the Tokyo subway system in 1995, killing 12 people and injuring more than 5,000.

Japan also has a significant minority of Christians, estimated at about 1 million. Portuguese and Spanish missionaries introduced Christianity to Japan in the 16th century. The religion made strong inroads there until the Japanese government banned it as a potential threat to the country’s political sovereignty from the mid-17th century to the mid-19th century. Today, about two-thirds of Japan’s Christians are Protestants, and about one-third are Roman Catholics. Small communities of followers of other world faiths live in Japan as well.

With an adult literacy rate exceeding 99 percent, Japan ranks among the top nations in the world in educational attainment. Schooling generally begins before grade one in preschool (yôchien) and is free and compulsory for elementary and junior high school (grades 1 through 9). More than 99 percent of elementary school-aged children attend school. Most students who finish junior high school continue on to senior high school (grades 10 through 12). Approximately one-third of senior high school graduates then continue on for higher education. Most high schools and universities admit students on the basis of difficult entrance examinations. Competition to get into the best high schools and universities is fierce because Japan’s most prestigious jobs typically go to graduates of elite universities.

About 1 percent of elementary schools and 5 percent of junior high schools are private. Nearly 25 percent of high schools are private. Whether public or private, high schools are ranked informally according to their success at placing graduates into elite universities. In 1998 there were 604 four-year universities in Japan and 588 two-year junior colleges. Important and prestigious universities include the University of Tokyo, Kyôto University, and Keio University in Tokyo.

The school year in Japan typically runs from April through March and is divided into trimesters separated by vacation holidays. Students attend classes five full weekdays in addition to half days on Saturdays, and on average do considerably more homework each day than American students do. In almost all schools, students wear uniforms and adhere to strict rules regarding appearance.

In addition to their regular schooling, some students—particularly students at the junior high school level—enroll in specialized private schools called juku. Often translated into English as «cram schools,» these schools offer supplementary lessons after school hours and on weekends, as well as tutoring to improve scores on senior high school entrance examinations. Students who are preparing for college entrance examinations attend special schools called yobikô. A disappointing score on a college entrance examination means that a student must settle for a lesser college, decide not to attend college at all, or study for a year or more at a yobikô in preparation to retake the examination.

The early history of education in Japan was rooted in ideas and teachings from China. In the 16th and early 17th centuries, European missionaries also influenced Japanese schooling. From about 1640 to 1868, during Japan’s period of isolation under the Tokugawa shoguns, Buddhist temple schools called terakoya assumed responsibility for education and made great strides in raising literacy levels among the general population. In 1867 there were more than 14,000 temple schools in Japan. In 1872 the new Meiji government established a ministry of education and a comprehensive educational code that included universal primary education. During this period, Japan looked to nations in Europe and North America for educational models. As the Japanese empire expanded during the 1930s and 1940s, education became increasingly nationalistic and militaristic.

After Japan’s defeat in World War II, the educational system was revamped. Changes included the present grade structure of six years of elementary school and three years each of junior and senior high school; a guarantee of equal access to free, public education; and an end to the teaching of nationalist ideology. Reforms also sought to encourage students’ self-expression and increase flexibility in curriculum and classroom procedures. Nevertheless, some observers still believe that education in Japan is excessively rigid, favoring memorization of facts at the expense of creative expression, and geared to encouraging social conformity.

A largely homogeneous society, Japan does not exhibit the deep ethnic, religious, and class divisions that characterize many countries. The gaps between rich and poor are not as glaring in Japan as they are in many countries, and a remarkable 90 percent or more of Japanese people consider themselves middle class. This contrasts with most of Japan’s previous recorded history, when profound social and economic distinctions were maintained between Japan’s aristocracy and its commoners. Two periods of social upheaval in the modern era did much to soften these class divisions. The first was the push for modernization under the Meiji government at the end of the 19th century; the second was the period of Allied occupation after World War II. Among the most profound of the transformations that took place in the modern era was the empowerment of individuals rather than extended families and family lines as the fundamental units of society. As a result of this change, Japanese men and women experienced greater freedom in making personal decisions, such as choosing a spouse or career.

Nevertheless, some significant social differences do exist in Japan, as evidenced by the discrimination in employment, education, and marriage faced by the country’s Korean minority and by its burakumin. Burakumin means «hamlet people,» a name that refers to the segregated villages these people lived in during Japan’s feudal era. Burakumin are indistinguishable from Japanese racially or culturally, and today they generally intermingle with the rest of the population. However, for centuries they were treated as a separate population because they worked in occupations that were considered unclean, such as disposing of the dead and slaughtering animals. Despite laws to the contrary, their descendants still suffer discrimination in Japan. The number of burakumin is thought to be about 3 million, or about 2 percent of the national population. They are scattered in various parts of the country, usually in discrete communities, with the largest concentrations living in the urban area encompassing Ôsaka, Kôbe, and Kyôto.

Despite the shift toward individual empowerment, Japanese society remains significantly group-oriented compared to societies in the West. Japanese children learn group consciousness at an early age within the family, the basic group of society. Membership in groups expands with age to include the individual’s class in school, neighborhood, extracurricular clubs during senior high school and college, and, upon entering adulthood, the workplace. All along, the individual is taught to be dedicated to the group, to forgo personal gain for the benefit of the group as a whole, and to value group harmony. At the highest level, the Japanese nation as a whole may be thought of as a group to which its citizens belong and have obligations. The form of character building that instills these values is called seishin shûyô.

Most groups are structured hierarchically. Individual members have a designated rank within the group and responsibilities based on their position. Seniority has traditionally been the main qualification for higher rank, and socialization of young people in Japan emphasizes respect and deference to one’s seniors.

Historically, most Japanese people lived in agricultural villages or small fishing settlements along the coast. Now, most of the population resides in metropolitan areas. Japan’s agricultural population, which has been declining since the 1950s, constituted only about 5 percent of the total population in 1996. A disproportionate fraction of the population that has remained to live and work in Japan’s agricultural areas is elderly because the majority of migrants to cities are young.

Everyday life for most urban Japanese involves work in an office, store, factory, or other segment of the metropolitan economy. Daily commutes by bus, train, or subway are typically long, particularly in Tokyo. The commute is also extraordinarily crowded. During rush hours, some commuter lines employ «pushers» to shove riders into jam-packed train or subway cars before the doors slide closed.

Most houses and apartments are small in comparison to those in many other developed countries because of the country’s high population density and costly land. Nevertheless, many Japanese enjoy a high standard of living and comforts such as the latest fashions in clothing, new appliances and electronics, and new models of automobiles. Sundays are the busiest shopping days in Japan. During the afternoon hours, department stores and shopping malls are jammed with crowds of bargain hunters. Japanese also enjoy travel and often go abroad or to popular domestic resorts during holidays. Between 1968 and 1994 the number of Japanese traveling abroad each year increased from 344,000 to 13.5 million. Among the most popular destinations are Hawaii and the West Coast of the United States, New York City, Australia, Hong Kong, and the major capitals of Europe.

Japanese life blends traditions from the past with new activities, many borrowed from other cultures. The Japanese diet, for example, emphasizes rice, seafood, and other items that have been staples in the society for centuries, but also includes international cuisine such as Italian and Chinese dishes, and American-style fast-food hamburgers and french fries. Likewise, Japanese sports fans give equal weight to sumo, Japan’s traditional style of wrestling, as to baseball, imported from the United States in the late 19th century. Contemporary weddings in Japan often combine traditional Shinto ceremonies, such as ritual exchanges of sake (rice wine), with Western-style exchanges of wedding bands. Arranged marriages, common in Japan before World War II, have declined in favor of so-called love marriages based on a couple’s mutual attraction. Nevertheless, the tradition of family involvement in selecting a mate endures, and arranged marriages still occur.

Major holiday celebrations in Japan include Obon, a traditional midsummer honoring of ancestral spirits, and the New Year, when people eat special foods, visit Shinto shrines, and call on family and friends. When Japan’s cherry trees blossom, signaling the arrival of spring, people celebrate with picnics under the trees. Each year on May 5 the Japanese celebrate Children’s Day, when families with young boys fly giant carp (a symbol of success) made of cloth or paper from the roofs of their houses. Adult’s Day, on January 15, is celebrated to honor all young people who turned 20 in the past year, and Respect for the Aged Day is observed on September 15. The emperor’s birthday is also a national holiday. During Golden Week, a time in late April and early May when several holidays come together, many Japanese enjoy travel and leisure activities, such as golf, tennis, and hiking.

Japanese engage in ritual gift giving during New Year’s and at midsummer. Strong social obligations dictate who must give gifts to whom, and selecting a gift involves elaborate rules and customs about what kinds of gifts are appropriate in the precise situation. The total cost of gifts exchanged is high, causing the gift-giving tradition to become a significant financial support for Japan’s manufacturing sector, the country’s retail enterprises, and its package delivery services.

For the most part, Japan is a stable country with a high degree of domestic tranquility. Yet the country faces a number of social problems, some of them new and worsening, others long-term and slowly improving. Some of the most difficult recent troubles arose from the economic recession that began in Japan in the 1990s. Until recently, unemployment was virtually unknown in Japan to all but the oldest citizens who lived through the economic chaos of the years immediately after World War II. However, during the 1990s unemployment rose as companies and financial institutions that were once thought to be financially solid cut back on their workforces or closed altogether. Lifetime job security, once a hallmark of Japan’s economy, no longer exists in many companies, and experienced workers now find themselves competing for inferior jobs with younger people looking for entry-level positions. The younger generation in turn is finding it hard to enter the economy because jobs that were once plentiful for high school and college graduates are now in short supply.

The prolonged recession is one of the chief causes of an increase in homelessness in Japan. Tokyo and other cities have thousands of homeless people, mostly middle-aged and older men. Quite a few of them were brought to these circumstances by alcoholism or mental illness, but the number of people who are homeless because of unemployment has risen. Sometimes people who lose their jobs or suffer the failure of a business feel too ashamed to face their families in Japan’s tradition-bound society. These people exile themselves to one of the many communities of newly homeless people.

Crime is another growing problem. Although Japan is one of the safest countries in the world, Japanese are greatly concerned about recent increases in violent crime and crimes against property. Some fault the growing number of foreigners in Japan for rising crime, but most attribute the problem to the combination of economic recession and the high desirability of consumer goods among the younger generation. A particularly disturbing aspect of the problem reported widely in the Japanese media has been the large increase in prostitution among high school girls. These girls are seeking money for the latest clothing fashions, expensive concert tickets, and other desired items. Organized crime by mobsters known as yakuza continues to be a strong force in Japan, controlling prostitution, pornography, and gambling.

An important long-term social problem in Japan concerns the status of women. The Japanese constitution forbids discrimination on the basis of sex, and Japanese law affords women the same economic and social rights as men. Nevertheless, fewer women than men attend four-year universities, and in general women do not have equal access to employment opportunities and advancement within the ranks of a company or along a career path. Efforts to increase women’s opportunities have enabled more women to succeed in business or professions. However, the attitude that women should stay home to be wives and mothers remains more pervasive in Japan than in many other industrialized countries and is a roadblock to many women who opt for other challenges.

Japan has a well-developed social welfare system designed to protect the quality of life of legal residents against a broad range of social and economic risks. The system has four principal components. First, through public assistance it provides a basic income for people unable to earn enough on their own for subsistence. Second, it provides citizens with social insurance in the form of health and medical coverage, unemployment compensation, and public pensions. Most social insurance programs are funded by contributions from employers and employees, as well as by subsidies from government funds. Third, the system provides social welfare services to address various special needs of the aged, the disabled, and children. And finally, it provides public health maintenance to attend to sanitation and environmental issues and to safeguard the public from infectious diseases.

The cost of social welfare has risen in Japan and accounted for nearly 20 percent of the national budget in 1995. The recession of the 1990s, which added to the number of people receiving public assistance, has posed major challenges for Japan’s welfare system. Furthermore, with the country’s rapidly aging population, providing for the needs of the elderly is becoming harder for the government. Subsidized nursing homes, regular health examinations, low-cost medical care, home care, and recreational activities at community centers are services for the elderly that may be impossible to provide in the future. The problem is made worse because the time-honored tradition of family members taking care of aged relatives is declining in Japan, putting more of the burden for care on government.

The People and Society section of this article was contributed by Roman Cybriwsky.

Japanese cultural history is marked by periods of extensive borrowing from other civilizations, followed by assimilation of foreign traditions with native ones, and finally transformation of these elements into uniquely Japanese art forms. Japan borrowed primarily from China and Korea in premodern times and from the West in the modern age.

Cultural imports began to arrive in Japan from continental East Asia around 300 BC, starting with agriculture and the use of metals. These new technologies eventually helped build a more complex Japanese society, whose most remarkable and enduring structures were huge, key-shaped tombs. Named for these tombs, the Kofun period endured from the late 3rd to the 6th century AD.

In the middle of the 6th century, Japan embarked on a second phase of extensive cultural borrowing from the Asian continent—largely from China. Among the major imports from China were Buddhism and Confucianism. Buddhism was particularly important, not only as a religion but also as a source of art, especially in the form of temples and statues. Although Buddhism eventually became a major religion of Japan, some evidence indicates that the Japanese initially were drawn more to its architecture and art than to its religious doctrines.

In Japan’s first state, the arts were almost exclusively the preserve of the ruling elite, a class of courtiers who served as ministers to the emperor. For most of the 8th century the court was located at Nara, the first capital of Japan, which gave its name to the Nara period (710-794). At the end of the 8th century the capital moved to Heian-kyô (modern Kyôto), and Japan entered its classical age, known as the Heian period (794-1185). By the beginning of the 11th century, the emperor’s courtiers had developed a brilliant culture and lifestyle that owed much to China but was still uniquely Japanese. Poetry flourished especially, but important developments also took place in prose literature, architecture (especially residential architecture), music, and painting (both Buddhist and secular).

As the Heian court reached its height of cultural brilliance, however, a class of warriors (samurai) emerged in the provinces. In the late 12th century the first warrior government (known as a shogunate) was established at Kamakura. Japan entered a feudal era of frequent wars and samurai dominance that would last for nearly four centuries, first under the Kamakura and then under the Ashikaga shoguns.

The culture of the Kamakura period (1185-1333) is noteworthy particularly for its poetry, prose, and painting. Although the Kyôto courtiers lost their political power to the samurai, they continued to produce outstanding poetry. Warrior society contributed to the national culture as well. Anonymous war tales were among the major achievements in prose. Painters produced narrative picture scrolls depicting military and religious subjects such as battles, the lives of Buddhist priests, and histories of Buddhist temples and of shrines of Japan’s native religion, Shinto.

The Kamakura shogunate ended with a brief attempt to restore imperial rule. Then in 1338 the Ashikaga shoguns established their seat near the emperor’s court in the Muromachi district of Kyôto. During the reign of the Ashikaga (known as the Muromachi period), which lasted until 1573, Japan again sent missions to China. This time they brought back the latest teachings of Zen Buddhism and Neo-Confucianism, as well as countless objects of art and craft. Zen Buddhism, which had been introduced to Japan during the Kamakura period, contributed to the development of Muromachi-period artistic forms. Chinese monochrome ink painting became the principal painting style. Dramatists created classical nô theater, performed for the upper classes of society. And beginning in the 15th century, the tea ceremony, a gathering of people to drink tea according to prescribed etiquette, evolved. The poetic form of renga, or linked verse, also developed at this time. The linked verse style, in which several poets take turns composing alternate verses of a single long poem, became popular among all classes of society.

In 1603 a third warrior government, the Tokugawa shogunate, established itself in Edo (present-day Tokyo), and Japan entered a long period of peace that historians consider the beginning of the country’s modern age. During this era, known as the Tokugawa period (1603-1867), Japan adopted a policy of national seclusion, closing its borders to almost all foreigners. Domestic commerce thrived, and cities grew larger than they had ever been. In great cities such as Edo, Ôsaka, and Kyôto, performers and courtesans mingled with rich merchants and idle samurai in the restaurants, wrestling booths, and brothels of the areas known as the pleasure quarters. These so-called chônin, or townsmen, the urban class dominated by merchants, produced a new, bourgeois culture that included 17-syllable haiku poetry, prose literature of the pleasure quarters, the puppet and kabuki theaters, and the art of the wood-block print.

Japan’s seclusion policy ended when Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States sailed into Edo Bay in 1853 and established a treaty with Japan the following year. The Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown in the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and Japan entered the modern world. During the early years of the new order, known as the Meiji period (1868-1912), Western culture largely overwhelmed Japan’s native heritage. Ignoring many of their traditional arts, the Japanese set about adopting Western artistic styles, literary forms, and music. By the end of the Meiji period, however, the Japanese not only had resuscitated many traditional art forms but also were making impressive advances in modern styles of architecture, painting, and the novel.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Japan has moved steadily into the stream of international culture. Japan’s influence on that culture has been especially pronounced since the end of World War II (1939-1945). Japanese movies, for example, have received international recognition and acclaim, and Japanese novels have been translated into English and other languages. Meanwhile, traditional Japanese culture has flowed around the world, influencing styles in design, architecture, and various crafts, such as ceramics and textiles.

Throughout most of their history, the Japanese people have written poetry and prose in both Chinese and Japanese. This section deals mainly with literature written in the Japanese language.

Japan’s earliest literary writings are simple poems found in the country’s oldest existing books, the Koji-ki (Records of Ancient Matters, 712) and the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720) of the early Nara period. The mid-Nara period witnessed the compilation of Manyôshû (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), an anthology of some 4,500 poems written in the 7th and 8th centuries. Courtiers wrote most of the poems in Manyôshû, the great majority of them in the 5-line, 31-syllable waka (or tanka) form. Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, the best known of the poets, also wrote in a longer form that makes up a small percentage of the poems in the anthology. Some of the poems are celebrations of public events, such as coronations and imperial hunts, but even at this early time Japanese poetry was primarily personal. Its two main subjects were the beauties of nature, especially as found in the changing seasons, and heterosexual romantic love.

During the Heian period, court poets, using the waka form exclusively, reduced the range of poetic topics. Proper subjects had to meet the poets’ ideal of courtliness (miyabi) and demonstrate a sensitivity to the fragile beauties of nature and the emotions of others, an aesthetic known as mono no aware. The Kokinshû (Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems, begun in 905) set the standard for all future court poetry. Meanwhile, the invention of the kana syllabary (in which each symbol represents a syllable) enabled the Japanese to write freely in their own language for the first time. (Previously, most writing was in Chinese.) The invention of kana also stimulated the development of a prose literature. Court women took the lead in writing prose, using forms such as the fictional diary and the miscellany, a collection of jottings, anecdotes, lists, and the like. The two greatest Heian prose writings were the work of court women: Makura no sôshi (Pillow Book), a miscellany by Sei Shônagon;, and Genji monogatari (Tale of Genji, 1010?) by Murasaki Shikibu, a lengthy novel evoking court life during the mid-Heian period.

The early Kamakura period saw the production of two great works of literature: Shin kokinshû (New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems, 1205?) and Hôjôki (An Account of My Hut, 1212). Shin kokinshû, which ranks with Kokinshû as the finest of the court poetry anthologies, stresses achieving «depth» in verse through the application of aesthetic values such as yûgen (mystery and depth). Hôjôki describes the attempts of its author, former courtier and priest Kamo no Chômei, to divest himself of all but the most minimal material possessions to prepare himself, upon death, to enter the Pure Land paradise of the Amida Buddha.

The Heike monogatari (Tale of the Heike, begun 1220?) recounts the story of the war between the Taira clan (also known as the Heike) and the Minamoto clan during the late 12th century. It ranks second only to the Tale of Genji among the great Japanese prose writings of premodern times. The tale evokes the lives of both the warrior and the courtier elites during the transition from the ancient courtly age to the feudal age. The product of more than a century and a half of textual development, Heike monogatari was not completed until the late 14th century.

One of the most important literary developments of the middle and late Muromachi period was linked verse poetry (renga). As the creative potential of the classical waka declined, linked verse gained great popularity. Renga masters, such as Sôgi in the late 15th century, became famous not only for their poetry but also as traveling teachers who spread the linked verse method throughout the country.

In the Tokugawa period, townsmen living in the great cities produced most of Japan’s major literature. Haiku, consisting of just the first seventeen syllables of the waka, became a means for expressing emotional insights, or enlightenments, especially when composed by a master such as Bashô. Even today, haiku enjoys enormous popularity in Japan, and over the years countless non-Japanese have tried their hands at composing haiku. The last years of the 17th century and the first years of the 18th century saw an epoch of cultural flourishing known as the Genroku period. Much of Genroku culture focused on the pleasure quarters of the great cities. Prose writer Saikaku gained fame for his stories about the affairs of the pleasure quarters, especially about courtesans and prostitutes and the merchants and samurai they entertained.

Although the modern age has seen important developments in poetry, the novel is the literary medium that has enjoyed the most artistic success. Since Futabatei Shimei published Ukigumo (The Drifting Cloud, 1887-1889), considered Japan’s first modern novel, Japanese writers have steadily gained international prominence. Inspired both by their native literary traditions and by writings in European languages, including English, French, German, and Russian, Japanese writers have created a corpus of fine novels. One of Japan’s most acclaimed novelists is Tanizaki Junichirô, author of Sasameyuki (1943-1948; translated in English as The Makioka Sisters, 1957), a re-creation of the life of an Ôsaka family in the years just before World War II. Another is Kawabata Yasunari, winner of the Nobel Prize for literature. In his novels, Kawabata draws heavily on traditional Japanese literary styles, and his own style has been characterized as haiku-like. Prominent late 20th-century writers include Ôe Kenzaburô, the second Japanese recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature, and Abe Kôbô. See also Japanese Literature.

Japan’s oldest indigenous art is handmade clay pottery, called Jômon, or cord pattern, pottery. Produced beginning about 10,000 BC, it marked the beginning of a rich ceramic-making tradition that has continued to the present day. During the Kofun period, sculptors fashioned terra cotta figurines called haniwa that depicted a variety of people (including armor-clad warriors and shamans), animals, buildings, and boats. The figurines were placed on the tombs of Japan’s rulers.

When Buddhism arrived in Japan, its architecture and art profoundly influenced native styles. Hôryûji temple, built near Nara in the early 7th century, has the world’s oldest wooden buildings, as well as an impressive collection of Buddhist paintings and statues. During the Nara period, many new temples were erected in and around the city. The most famous temple is Tôdaiji, where an approximately 16-m (53-ft) Daibutsu (Great Buddha) statue is housed in the world’s largest wooden building. Possibly inspired by the temples of Buddhism, a distinct style of Shinto architecture began to develop. Drawing on native traditions such as raised floors and thatched roofs with deep eaves, Shinto produced artistically fine structures such as the Ise Shrine and the Izumo Shrine.

After the emperor’s court moved to Heian-kyô in 794, the construction of Buddhist temples continued. Many were now built in remote areas, where they were designed to blend harmoniously with their natural settings. The esoteric Shingon sect of Buddhism arrived from China creating a demand among Heian courtiers for the visual and plastic arts of Shingon. These included mandalas (diagrams of the spiritual universe used for meditation) and paintings and statues of fantastic beings, sometimes fierce with extra limbs or heads. Beautifully appointed residences (called shinden residences) also began to appear at this time. These rambling structures opened onto raked-sand gardens, which featured ponds fed by streams that often flowed under the residences’ raised floors. Although no examples of shinden residences exist today, narrative picture scrolls from the late Heian period depict these residences of the courtier elite. These scrolls, known as emakimono, represent one of the first forms of indigenous, secular painting in Japan. One of the most impressive examples of emakimono is an illustrated version of the 11th century prose epic, the Tale of Genji.

During the early Kamakura period, Nara-era traditions of realistic sculpture inspired a sculptural revival that produced dynamic, individualized figures. But probably the finest products of Kamakura art were narrative picture scrolls. Indeed, with the notable exception of the earlier Tale of Genji scroll, most of the finest surviving emakimono date from the Kamakura period. These include the Ippen scroll, which depicts the journeys of Ippen, an evangelist of Pure Land Buddhism. The scroll portrays landscape scenes, towns, Buddhist temples, and Shinto shrines throughout Japan.

Architecturally, the Muromachi period is best remembered for the construction of Zen temples. Notable examples are the so-called «Five Mountains» temples of Kyôto, which were situated mainly around the outskirts of the city to take advantage of the mountain scenery that borders Kyôto on three sides. These temples became the settings for most of the best dry landscape gardens (waterless gardens of sand, stone, and shrubs) constructed in Muromachi times. Two of Japan’s most famous buildings, the Golden and Silver pavilions, are on Zen temple grounds. The creation of the tea ceremony accompanied the development in the 15th century of the shoin style of room construction, featuring rush matting (tatami) for floors, sliding doors, and built-in alcoves and asymmetrical shelves. In painting, the Muromachi period is best known for a monochrome ink style that originated in China during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The landscape paintings of masters such as Shûbun and Sesshû exemplify the adaptation of the style in Japan.

Many schools of painting flourished during the Tokugawa period, including one that used Western techniques such as shading and foreshortening to produce the illusion of space and depth. The most popular by far, however, was genre art, or art depicting people at work and play. From mid-Tokugawa times, the most popular medium for genre art was the wood-block print. Artists often used the wood-block print technique to create ukiyo-e, or «pictures of the floating world» (referring to the pleasure quarters of Japan’s great cities). Among the favorite subjects of ukiyo-e artists were courtesans and kabuki actors. The artist Utamaro is particularly known for his tall, willowy courtesans, while Sharaku famously captured the spirit and emotions of kabuki actors. In the late Tokugawa period, genre art was dominated by two artists, Hokusai and Hiroshige. Hokusai became famous throughout the world for The Wave (1831), a view of Mount Fuji through a huge, curling wave. Hiroshige created the print series Fifty-three Stations of the Tôkaidô (1833), which is considered a masterpiece and is well known outside Japan.

One of the greatest architectural works of the Tokugawa period was the Katsura Detached Palace, built in the 17th century. Its clean, geometric lines had a powerful influence on post-World War II residential architecture in many foreign countries. By contrast, the mausoleum of the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu at Nikkô, built during the same period, is extraordinary for its elaborate decoration.

Among Japan’s best-known modern architects is Tange Kenzô. His buildings won international fame and include the Hall Dedicated to Peace at Hiroshima and the main Sports Arena for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Japanese Art and Architecture.

The earliest reported form of music and dance in Japan was gigaku, imported from China by a Korean performer sometime in the early 6th century. In gigaku, masked dancers performed dramas to the accompaniment of flute, drum, and gong ensembles.

The ancient music and dance of Shinto is called kagura. In kagura, performers danced for the pleasure of the gods and expressed prayers asking for prolonged or revitalized life. Drums, flutes, and sometimes cymbals provided music, and as in gigaku, the dancers often wore masks.

The ritual music of the emperor’s court, gagaku, accompanied dancing called bugaku. In addition to the instruments already mentioned, gagaku employed a type of double-reed pipe or oboe (hichiriki) and a mouth organ (shô). Of all the musical sounds of Japan, the exotic tones of these two instruments are probably the most unusual to Western ears.